Seeking and Plant Medicine Becomings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FM2- Aims & Scope

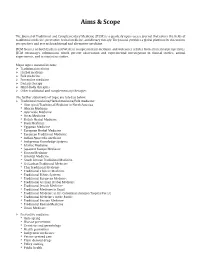

Aims & Scope The Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine (JTCM) is a quarterly open-access journal that covers the fields of traditional medicine, preventive herbal medicine, and dietary therapy. The Journal provides a global platform for discussion, perspectives and research traditional and alternative medicine. JTCM focuses on both Eastern and Western complementary medicine and welcomes articles from all medical perspectives. JTCM encourages submissions which present observation and experimental investigation in clinical studies, animal experiments, and in vivo/vitro studies. Major topics covered include: ¾ Traditional medicine ¾ Herbal medicine ¾ Folk medicine ¾ Preventive medicine ¾ Dietary therapy ¾ Mind-body therapies ¾ Other traditional and complementary therapies The further statements of topic are listed as below: ¾ Traditional medicine/Herbal medicine/Folk medicine: • Aboriginal/Traditional Medicine in North America • African Medicine • Ayurvedic Medicine • Aztec Medicine • British Herbal Medicine • Bush Medicine • Egyptian Medicine • European Herbal Medicine • European Traditional Medicine • Indian Ayurvedic medicine • Indigenous Knowledge Systems • Islamic Medicine • Japanese Kampo Medicine • Korean Medicine • Oriental Medicine • South African Traditional Medicine • Sri Lankan Traditional Medicine • Thai Traditional Medicine • Traditional Chinese Medicine • Traditional Ethnic Systems • Traditional European Medicine • Traditional German Herbal Medicine • Traditional Jewish Medicine • Traditional Medicine in Brazil -

Understanding Complementary Therapies a Guide for People with Cancer, Their Families and Friends

Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends Treatment For information & support, call Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends First published October 2008. This edition April 2018. © Cancer Council Australia 2018. ISBN 978 1 925651 18 8 Understanding Complementary Therapies is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy is up to date. Editor: Jenny Mothoneos. Designer: Eleonora Pelosi. Printer: SOS Print + Media Group. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Cancer Information Working Group initiative. We thank the reviewers of this booklet: Suzanne Grant, Senior Acupuncturist, Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, NSW; A/Prof Craig Hassed, Senior Lecturer, Department of General Practice, Monash University, VIC; Mara Lidums, Consumer; Tanya McMillan, Consumer; Simone Noelker, Physiotherapist and Wellness Centre Manager, Ballarat Regional Integrated Cancer Centre, VIC; A/Prof Byeongsang Oh, Acupuncturist, University of Sydney and Northern Sydney Cancer Centre, NSW; Sue Suchy, Consumer; Marie Veale, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council Queensland, QLD; Prof Anne Williams, Nursing Research Consultant, Centre for Nursing Research, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, and Chair, Health Research, School of Health Professions, Murdoch University, WA. We also thank the health professionals, consumers and editorial teams who have worked on previous editions of this title. This booklet is funded through the generosity of the people of Australia. Note to reader Always consult your doctor about matters that affect your health. This booklet is intended as a general introduction to the topic and should not be seen as a substitute for medical, legal or financial advice. -

Understanding Complementary Therapies a Guide for People with Cancer, Their Families and Friends

Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends Treatment www.cancerqld.org.au Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends First published October 2008. This edition June 2012. © The Cancer Council NSW 2012 ISBN 978 1 921619 67 0 Understanding Complementary Therapies is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy of the booklet is up to date. To obtain a more recent copy, phone Cancer Council Helpline 13 11 20. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Publications Working Group Initiative. We thank the reviewers of this edition: Dr Vicki Kotsirilos, GP, Past founding president of Australasian Integrative Medicine Association, VIC; Annie Angle, Cancer Council Helpline Nurse, Cancer Council Victoria; Dr Lesley Braun PhD, Research Pharmacist, Alfred Hospital and Integrative Medicine Education and Research Group, VIC; Jane Hutchens, Registered Nurse and Naturopath, NSW; Bridget Kehoe, Helpline Nutritionist, Cancer Council Queensland; Prof Ian Olver, Chief Executive Officer, Cancer Council Australia, NSW; Carlo Pirri, Research Psychologist, Faculty of Health Sciences, Murdoch University, WA; Beth Wilson, Health Services Commissioner, VIC. We are grateful to the many men and women who shared their stories about their use of complementary therapies as part of their wider cancer care. We would also like to thank the health professionals and consumers who worked on the previous edition of this title, and Vivienne O’Callaghan, the orginal writer. Editor: Jenny Mothoneos Designer: Eleonora Pelosi Printer: SOS Print + Media Group Cancer Council Queensland Cancer Council Queensland is a not-for-profit, non-government organisation that provides information and support free of charge for people with cancer and their families and friends throughout Queensland. -

Aboriginal Healing Practices and Australian Bush Medicine

Philip Clarke- Aboriginal healing practices and Australian bush medicine Aboriginal healing practices and Australian bush medicine Philip Clarke South Australian Museum Abstract Colonists who arrived in Australia from 1788 used the bush to alleviate shortages of basic supplies, such as building materials, foods and medicines. They experimented with types of material that they considered similar to European sources. On the frontier, explorers and settlers gained knowledge of the bush through observing Aboriginal hunter-gatherers. Europeans incorporated into their own ‘bush medicine’ a few remedies derived from an extensive Aboriginal pharmacopeia. Differences between European and Aboriginal notions of health, as well as colonial perceptions of ‘primitive’ Aboriginal culture, prevented a larger scale transfer of Indigenous healing knowledge to the settlers. Since British settlement there has been a blending of Indigenous and Western European health traditions within the Aboriginal community. Introduction This article explores the links between Indigenous healing practices and colonial medicine in Australia. Due to the predominance of plants as sources of remedies for Aboriginal people and European settlers, it is chiefly an ethnobotanical study. The article is a continuation of the author’s cultural geography research that investigates the early transference of environmental knowledge between Indigenous hunter- gatherers and British colonists (1994: chapter 5; 1996; 2003a: chapter 13; 2003b; 2007a: part 4; 2007b; 2008). The flora is a fundamental part of the landscape with which human culture develops a complex set of relationships. In Aboriginal Australia, plants physically provided people with the means for making food, medicine, narcotics, stimulants, 3 Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia Vol. -

Modernization and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Caribbean Horticultural Village Author(S): Marsha B

Modernization and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Caribbean Horticultural Village Author(s): Marsha B. Quinlan and Robert J. Quinlan Source: Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun., 2007), pp. 169- 192 Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4499720 Accessed: 23-01-2018 22:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms American Anthropological Association, Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Medical Anthropology Quarterly This content downloaded from 69.166.46.145 on Tue, 23 Jan 2018 22:34:18 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Marsha B. Quinlan Department of Anthropology Washington State University Robert 3. Quinlan Department of Anthropology Washington State University Modernization and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Caribbean Horticultural Village Herbal medicine is the first response to illness in rural Dominica. Every adult knows several "bush" medicines, and knowledge varies from person to person. Anthropo- logical convention suggests that modernization generally weakens traditional knowl- edge. We examine the effects of commercial occupation, consumerism, education, parenthood, age, and gender on the number of medicinal plants freelisted by indi- viduals. -

AJHM Vol 24 (4) Dec 2012

Volume 24 • Issue 4 • 2012 Herbal Medicine A publication of the National Herbalists Association of Australia Australian Journal national herbalists of Herbal association of australia Medicine The Australian Journal of Herbal The NHAA was founded in Full ATSI membership Medicine is a quarterly publication of 1920 and is Australia’s oldest Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander practitioners who have undertaken formal the National Herbalists Association of national professional body of studies in bush medicine and Western herbal Australia. The Journal publishes material herbal medicine practitioners. medicine. on all aspects of western herbal medicine The Association is a non profit member Annual fee $60 and a $5 joining fee. and is a peer reviewed journal with an based association run by a voluntary Student membership Editorial Board. Board of Directors with the help of Students who are currently undertaking interested members. The NHAA is studies in western herbal medicine. Members of the Editorial Board are: involved with all aspects of western Annual fee $65 and a $10 joining fee. Ian Breakspear MHerbMed ND DBM DRM herbal medicine. Companion membership PostGradCertPhyto The primary role of the association is to Companies, institutions or individuals Sydney NSW Australia support practitioners of herbal medicine: involved with some aspect of herbal Annalies Corse BMedSc(Path) BHSc(Nat) medicine. Sydney NSW Australia • Promote, protect and encourage the Annual fee $160 and a $20 joining fee. Jane Frawley MClinSc BHSc(CompMed) DBM study, practice and knowledge of GradCertAppSc western herbal medicine. Corporate membership Blackheath NSW Australia • Promote herbal medicine in the Companies, institutions or individuals Stuart Glastonbury MBBS BSc(Med) DipWHM community as a safe and effective interested in supporting the NHAA. -

The Role of Traditional Medicine Practice in Primary Health Care Within Aboriginal Australia: a Review of the Literature Stefanie J Oliver

Oliver Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2013, 9:46 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/9/1/46 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE REVIEW Open Access The role of traditional medicine practice in primary health care within Aboriginal Australia: a review of the literature Stefanie J Oliver Abstract The practice of traditional Aboriginal medicine within Australia is at risk of being lost due to the impact of colonisation. Displacement of people from traditional lands as well as changes in family structures affecting passing on of cultural knowledge are two major examples of this impact. Prior to colonisation traditional forms of healing, such as the use of traditional healers, healing songs and bush medicines were the only source of primary health care. It is unclear to what extent traditional medical practice remains in Australia in 2013 within the primary health care setting, and how this practice sits alongside the current biomedical health care model. An extensive literature search was performed from a wide range of literature sources in attempt to identify and examine both qualitatively and quantitatively traditional medicine practices within Aboriginal Australia today. Whilst there is a lack of academic literature and research on this subject the literature found suggests that traditional medicine practice in Aboriginal Australia still remains and the extent to which it is practiced varies widely amongst communities across Australia. This variation was found to depend on association with culture and beliefs about disease causation, type of illness presenting, success of biomedical treatment, and accessibility to traditional healers and bush medicines. Traditional medicine practices were found to be used sequentially, compartmentally and concurrently with biomedical healthcare. -

Traditional Aboriginal Medicine Practice in the Northern Territory

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL MEDICINE PRACTICE IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Dr Dayalan Devanesen AM MBBS, DPH (Syd) Grad. Dip MGT, MHP (NSW) FRACMA, FAFPHM, FCHSE Paper presented at INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON TRADITIONAL MEDICINE BETTER SCIENCE, POLICY AND SERVICES FOR HEALTH DEVELOPMENT 11-13 September 2000 AWAJI ISLAND, JAPAN Organised by the World Health Organisation Centre for Health Development Kobe, Japan TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL MEDICINE PRACTICE IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA Dr. D. Dayalan Devanesen AM MBBS,DPH (Syd) Grad.Dip MGT, MHP (NSW) FRACMA,FAFPHM,FCHSE Director Primary Health Coordinated Care Northern Territory Health Services INTRODUCTION Australia is the only continent to have been occupied exclusively by nomadic hunters and gatherers until recent times. Carbon dating of skeletal remains proves that Australian Aboriginal history started some 40,000 years ago, long before Captain Cook landed on the eastern coast. This history is not completely lost. It is retained in the minds and memories of successive generations of Aboriginal people, passed on through a rich oral tradition of song, story, poetry and legend. According to Aboriginal belief all life, human, animal, plant and mineral are part of one vast unchanging network of relationships which can be traced to the great spirit ancestors of the Dreamtime. The Dreamtime continues as the ‘Dreaming’ or ‘Jukurrpa’ in the spiritual lives of Aboriginal people today. The events of the Dreamtime are enacted in ceremonies and dances and chanted incessantly to the accompaniment of didgeridoo or clapsticks. (Isaacs J 1980) The Dreaming is the source of the rich artistry, creativity and ingenuity of the Aboriginal people. In Australia, western health services have been superimposed on traditional Aboriginal systems of health care. -

THE ETHNOMEDICAL USE of BLACK DRINK to TREAT IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA in BASTIMENTOS, PANAMA by CASSANDRA NELSON DOOLEY (Under

THE ETHNOMEDICAL USE OF BLACK DRINK TO TREAT IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA IN BASTIMENTOS, PANAMA by CASSANDRA NELSON DOOLEY (Under the Direction of Diane K. Hartle) ABSTRACT Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is the most common nutritional deficiency in the world and intestinal parasites are estimated to be responsible for 30-57% of IDA cases (Yip 2001; Stoltzfus 1997). With an iron-poor diet and the high incidence of blood-sucking helminthes, the people in Bastimentos, Panama struggle with IDA. Black Drink is the ethnopharmacological answer to these pathologies. It is prepared with juice from Citrus aurantifolia, a cast iron vessel, and three biologically active plants, Stachytarpheta jamaicensis, Hyptis suaveolens, and Senna spp. The iron content and the pharmacognosy of the plants used to prepare Black Drink are investigated here. Analysis of Black Drink revealed an iron content of 2.5% indicating a dose of iron comparable to that prescribed by U.S. physicians for IDA. In Bastimentos, Panama, Black Drink is an effective, affordable, two-prong strategy for the treatment of IDA, intestinal parasite burdens, and is congruent with the popular therapeutic traditions. INDEX WORDS: Panama, Black Drink, iron deficiency anemia, intestinal parasites, hookworm, Stachytarpheta jamaicensis, Hyptis suaveolens, Senna spp., Citrus aurantifolia THE ETHNOMEDICAL USE OF BLACK DRINK TO TREAT IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA IN BASTIMENTOS, PANAMA by CASSANDRA NELSON DOOLEY B.S., The University of Georgia, 2001 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2004 © 2004 Cassandra Nelson Dooley All Rights Reserved THE ETHNOMEDICAL USE OF BLACK DRINK TO TREAT IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA IN BASTIMENTOS, PANAMA by CASSANDRA NELSON DOOLEY Major Professor: Diane Hartle, Ph.D. -

Shadow Medicine Among Milwaukee's Latino Community Ramona Chiquita Tenorio University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2013 Medicina del Barrio: Shadow Medicine Among Milwaukee's Latino Community Ramona Chiquita Tenorio University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Alternative and Complementary Medicine Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Tenorio, Ramona Chiquita, "Medicina del Barrio: Shadow Medicine Among Milwaukee's Latino Community" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 166. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/166 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MEDICINA DEL BARRIO: SHADOW MEDICINE AMONG MILWAUKEE’S LATINO COMMUNITY by Ramona C. Tenorio A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT MEDICINA DEL BARRIO: SHADOW MEDICINE AMONG MILWAUKEE’S LATINO COMMUNITY by Ramona C. Tenorio The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, under the supervision of Dr. Tracey Heatherington As a result of exclusionary state and federal policy decisions on immigration and health care, marginalized immigrants often seek health care in the shadows of U.S. cities through practitioners such as curandera/os* (healers), huesera/os* (bonesetters), parteras* (midwives), and sobadora/es* (massagers). under the radar of biomedical practice. This research focuses on this phenomenon in the context of globalized social networks and health care practices of marginalized Latino immigrants in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and within the broader economic and political context in this country. -

Bush Medicine PLANTS of the Illawarra

BUSH MEDICINE PLANTS OF THE ILLAWARRA TERRY RANKMORE Supported by a “Protecting Our Places” Grant from the NSW Environmental Trust DEDICATED to MY FAMILY AND THE ABORIGINAL PEOPLE OF THE ILLAWARRA. AUTHOR Terry Rankmore is the Agricultural Assistant at Lake Illawarra High School, NSW. Terry has had a long term interest in Australian native plants and their uses by the Traditional Owners of the land. He is an active member of Landcare Illawarra and Blackbutt Bushcare and has worked with several schools and Shellharbour City Council to develop Bush Tucker Gardens to celebrate Aboriginal heritage. Terry previously authored Murni Dhungang, Dharawal language for Animal Food, Plant Food, and introduced this book to over 40 schools in the Illawarra and Shoalhaven areas. SUPPORT Bush Medicines has been proudly supported by the Illawarra Aboriginal Corporation, Wollongong. PRINTER Hero Print GRAPHIC ARTIST Wade Ingold. www.2533graphicdesign.com.au PHOTOGRAPHY © Copyright Peter Kennedy. © Copyright Linda Faiers. Cover image by Linda Faiers. PUBLISHER The Illawarra Aboriginal Corporation received a Protecting Our Places grant from the NSW Environmental Trust, which has enabled Bush Medicines to be researched and published. Supported by a “Protecting Our Places” Grant from the NSW Environmental Trust BUSH MEDICINE PLANTS OF THE ILLAWARRA TERRY RANKMORE { 6 } BUSH MEDICINE PLANTS OF THE ILLAWARRA TERRY RANKMORE CONTENTS Acknowledgement to Country 10 Bush medicine today 11 Introduction 13 A cautionary note about plants 14 Re-vegetating degraded areas -

Understanding Complementary Therapies a Guide for People with Cancer, Their Families and Friends

Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends Cancer Treatment information For information & support, call Understanding Complementary Therapies A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends First published October 2008. This edition May 2015. © The Cancer Council NSW 2015. ISBN 978 1 925136 51 7 Understanding Complementary Therapies is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy is up to date. Editor: Cath Grove. Designer: Paula Marchant. Printer: SOS Print + Media Group. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Publications Working Group Initiative. We thank the reviewers of this edition: Dr Haryana Dhillon, Research Fellow, Survivorship Research Group, Deputy Director, Centre for Medical Psychology & Evidence-based Decision-making, University of Sydney, and Chair, Clinical Oncology Society of Australia Survivorship Group, NSW; Dr Kylie Dodsworth, GP, Vice- President, Australasian Integrative Medicine Association, SA; Lauren Muir, Accredited Practising Dietitian, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Shavita Patel, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA; A/Prof Evelin Tiralongo, Lecturer and Researcher in Complementary Medicine, School of Pharmacy, Griffith University, QLD; Gabrielle Toth, Consumer; Dr Xiaoshu Zhu, Director, Academic Program for Chinese Medicine, Senior Lecturer, School of Science and Health, and Researcher, National Institute of Complementary Medicine, University of Western Sydney, NSW. We thank the men and women who shared stories about their use of complementary therapies as part of their wider cancer care. We would also like to thank the health professionals and consumers who worked on the previous editions of this title, and Vivienne O’Callaghan, the original writer.