The Ratifiers' Theory of Officer Accountability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community

Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community Washington and Lee University May 2, 2018 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...3 Part I: Methodology: Outreach and Response……………………………………...6 Part II: Reflecting on the Legacy of the Past……………………………………….10 Part III: Physical Campus……………………………………………………………28 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….45 Appendix A: Commission Member Biographies………………………………….46 Appendix B: Outreach………………………………………………………………..51 Appendix C: Origins and Development of Washington and Lee………………..63 Appendix D: Recommendations………………………………………………….....95 Appendix E: Portraits on Display on Campus……………………………………107 Appendix F: List of Building Names, Markers and Memorial Sites……………116 2 INTRODUCTION Washington and Lee University President Will Dudley formed the Commission on Institutional History and Community in the aftermath of events that occurred in August 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. In February 2017, the Charlottesville City Council had voted to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee from a public park, and Unite the Right members demonstrated against that decision on August 12. Counter- demonstrators marched through Charlottesville in opposition to the beliefs of Unite the Right. One participant was accused of driving a car into a crowd and killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer. The country was horrified. A national discussion on the use of Confederate symbols and monuments was already in progress after Dylann Roof murdered nine black church members at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015. Photos of Roof posing with the Confederate flag were spread across the internet. Discussion of these events, including the origins of Confederate objects and images and their appropriation by groups today, was a backdrop for President Dudley’s appointment of the commission on Aug. -

Combined Obits 2000-2009

Name Obit Date Page Death Date Aab, Albert J p 4/23/2009 A08:1 4/21/2009 Aab, Jean Elizabeth p 7/30/2009 A15:2 7/28/2009 Aagesen, Clara E p 1/24/2009 A06:3 1/21/2009 Aagesen, Kenneth L. p 3/6/2001 A:10 3/4/2001 Aagesen, Robert L p 7/4/2005 A8:3 7/2/2005 Aaron, Paul Thomas p 2/7/2000 A8:5 2/5/2000 Aaron, Wilbert Lee p 1/22/2004 A10:1 1/16/2004 Aaron, William Donald 6/30/2005 A8:3 6/29/2005 Abbasspour, Khorshid sh 3/17/2004 A10:1 3/16/2004 Abbe, Lin J p 6/17/2004 A13:5 6/11/2004 Abbe, Sandra A 10/30/2001 A:10 10/28/2001 Abbey, Alice p 7/4/2006 A04:2 7/2/2006 Abbey, Gordon Robert 5/18/2002 A10:4 5/16/2002 Abbey, Mary Jane 4/19/2005 A8:3 4/17/2005 Abbey, Nellie M 5/2/2004 A15:4 4/24/2004 Abbiss, Anne E p 10/11/2009 A14:5 10/9/2009 Abbott, Alfred R p 10/11/2005 A7:6 10/10/2005 Abbott, Cornelia Edwards Heyder 1/26/2000 A10:4 1/14/2000 Abbott, Florence Bernice 7/1/2003 A8:1 6/28/2003 Abbott, Jeffory Allen 5/21/2001 A:11 5/18/2001 Abbott, Marylee E p 4/15/2005 A6:2 4/13/2005 Abbott, Michael S p 3/28/2009 A06:4 3/26/2009 Abbott, Miles Ray 6/4/2007 A05:1 6/1/2007 Abbott, Phyllis p 6/6/2008 A12:1 5/16/2008 Abbott, Ralph L. -

Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through His Life at Arlington House

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2020 The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House Cecilia Paquette University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Paquette, Cecilia, "The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House" (2020). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1393. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE THAT BUILT LEE Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House BY CECILIA PAQUETTE BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2017 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History September, 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2020 Cecilia Paquette ii This thesis was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in History by: Thesis Director, Jason Sokol, Associate Professor, History Jessica Lepler, Associate Professor, History Kimberly Alexander, Lecturer, History On August 14, 2020 Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. !iii to Joseph, for being my home !iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisory committee at the University of New Hampshire. -

“Light Horse Harry” Henry Lee and Washington County “Light Horse

“Light Horse Harry” Henry Lee and Washington County In the history of Southwestern Pennsylvania there have Washington County) which was the epicenter of the been many noteworthy personalities, but who are they farmer’s rebellion. Lee led the southern column and by and what did they do to catch our attention? One of November 1, they arrived in Uniontown. Gen. John them is Henry Lee III, who was born in Virginia on Neville and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamil- January 29, 1756 to Maj. Gen. Henry Lee II, and Lucy ton were in this group. Col. Presley Neville was in the Grymes. Lee’s family tree includes links to America’s northern column. founding fathers and European royalty. He graduated from the College of New Jersey (Princeton) and when On November 8 Lee issued a proclamation that the the Revolutionary War began, he was a Captain in a troops were there because the people of the United Virginia dragoon detachment. He was States were determined to uphold the new government next given the rank of Major and the they had just constituted. Lee identified to Gen. William command of a corps of cavalry and in- Irvine the leaders of the rebel- fantry called “Lee’s Legion.” For his lion who were to be arrested, horsemanship he was known as “Light and on November 12, in what Horse Harry.” He was made Lt. Colonel has been called “The Terrible and he served in three major southern Night” several score citizens battles, ending at the British surrender at were arrested. The march of Yorktown. -

Lee, Honor, and the Confederacy

1 Andy Haugen 5-8-11 History Senior Thesis Lee, Honor, and the Confederacy Honor played a vital role in southern culture and was not taken lightly, for one of the reasons the South seceded was that southerners believed their honor had been insulted. The traditions of the South demanded control of land and the independence to act for the good of family and community. The South began to feel the pressure of servitude to political forces that denounced practices like slavery, particularly in debates over the spread of slavery in western territories. Secession, then, can be understood as an effort to restore southern honor.1 One of Virginia’s leading gentlemen, Robert E. Lee, joined the Confederacy in 1861. With him, he brought not only his extraordinary military talents but an unwavering sense of honor and virtue that he possessed not only in wartime but throughout his entire life. For Lee, honor required action for the overall public good. Lee had devoted thirty years of his life to the U.S. Army yet during the Civil War he forfeited his Arlington Plantation along the Potomac River, had sons and relatives captured, and suffered physical hardships himself. If the Confederate cause was to succeed, Lee felt that private citizens and public figures would have to cooperate, sacrifice, and accept their duty. During the Civil War, the Confederate States of America learned quickly that the many independently functioning factions within their ranks did not have a cohesive intent or purpose. While Lee depended on honor and virtue to sustain the South, the very concept was virtually lost in the face of war. -

89 Geo. Wash. L. Rev

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\89-3\GWN302.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-MAY-21 13:47 War Powers Abrogation Jeffrey M. Hirsch* ABSTRACT The United States’ peacetime security is based entirely on its all-volunteer armed forces. These volunteers, split equally between full- and part-time ser- vicemembers, risk not only their health and safety, but also their economic stability when they are called away from home for training or active duty. Servicemembers’ duties also interfere with the demands of employers, credi- tors, and government agencies—which can result in job losses, financial diffi- culties, and other costs. As a result, the federal government has long used its constitutional war powers to enact legislation protecting servicemembers from many of these hardships. These statutes provide employment leave and an- tidiscrimination protection, tax relief, and special procedural rights that lessen the burden of military service to ensure that the United States has a sufficient number of well-trained soldiers. Despite these statutes’ importance to national security, their applicability to state entities is in doubt. Using the Supreme Court’s fluctuating state sover- eign immunity jurisprudence, many state employers have invoked sovereign immunity to bar servicemembers’ private claims for monetary relief. More often than not, courts have sided with the states and dismissed ser- vicemembers’ federal claims for want of jurisdiction. However, these decisions are based on erroneous interpretations of the Court’s doctrine of sovereign immunity. Under current law, the federal government’s ability to subject states to individual suits is analyzed from a historical perspective. The inquiry asks whether the states, in ratifying the Constitution, believed that they retained im- munity in a given area. -

Lee Family Member Faqs

HOME ABOUT FAMILY PAPERS REFERENCES RESOURCES PRESS ROOM Lee Family Member FAQs Richard Lee, the Immigrant The Lee Family Digital Archive is the largest online source for Who was RL? primary source materials concerning the Lee family of Richard Lee was the ancestor of the Lee Family of Virginia, many of whom played prominent roles in the Virginia. It contains published political and military affairs of the colony and state. Known as Richard Lee the Immigrant, his ancestry is not and unpublished items, some known with certainty. Since he became one of Virginia's most prominent tobacco growers and traders he well known to historians, probably was a younger son of a substantial family involved in the mercantile and commercial affairs of others that are rare or have England. Coming to the New World, he could exploit his connections and capital in ways that would have been never before been put online. impossible back in England. We are always looking for new When was RL Born? letters, diaries, and books to add to our website. Do you Richard Lee was born about 1613. have a rare item that you Where was RL Born? would like to donate or share with us? If so, please contact Richard Lee was born in England, but no on knows for sure exactly where. Some think his ancestors came our editor, Colin Woodward, at from Shropshire while others think Worcester. (Indeed, a close friend of Richard Lee said Lee's family lived in (804) 493-1940, about how Shropshire, as did a descendent in the eighteenth century.) Attempts to tie his ancestry to one of the dozen or you can contribute to this so Lee familes in England (spelled variously as Lee, Lea, Leight, or Lega) that appeared around the time of the historic project. -

2017-Annual-Report.Pdf

2017 ANNUAL REPORT IMPROVING GOVERNANCE IN A TIME OF TRANSITION rookings research is firmly rooted in observed facts, empirical BB data, and an institutional commitment to developing practical solutions to the most vexing policy challenges facing society, in the United States and around the world. This way of operating is necessary in an ever-more polarized Washington, where like-minded people are drawn to information sources that reinforce their increasingly entrenched worldviews and even facts are the subject of debate. For more than 100 years, Brookings has built a reputation for quality, independence, and impact on the value proposition that thoughtful, unbiased analyses lead to good policies, which are at the heart of good governance. This is a constant, even in times of transition in administrations and shifting global alliances. 1 CO-CHAIRS’ MESSAGE rookings is more important PHOTO: KATHERINE LAMBERT KATHERINE PHOTO: BB than ever. There has never been a greater need for indepen- dent, high-quality research that has a genuine impact on the most pressing matters of public policy. We can fulfill this purpose because of our Board’s vision and oversight, our leadership’s strong management, and the support of our many donors, whose names you can read in the Honor Roll at the end of this report. We are deeply grateful to them all. The Brookings 2.0 strategic plan that we began implementing in 2016 brings a new framework and urgency to our efforts, and the pages that follow offer some details on our progress. The plan starts with expanding Brookings’s mission, from a focus on the efficient functioning of government to the improvement of governance at all levels of society. -

Volume 28 , Number 1

THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed Sparling, Writer, Scenic Hudson Editorial Board The Hudson River Valley Review Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Bard College a year by the Hudson River Valley COL Lance Betros, Professor and Head, Institute at Marist College. Department of History, U.S. Military James M. Johnson, Executive Director Academy at West Point Kim Bridgford, Professor of English, Research Assistants West Chester University Poetry Center Gabrielle Albino and Conference Gail Goldsmith Michael Groth, Professor of History, Wells College Hudson River Valley Institute Susan Ingalls Lewis, Associate Professor of History, Advisory Board State University of New York at New Paltz Peter Bienstock, Chair Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- Barnabas McHenry, Vice Chair Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Margaret R. Brinckerhoff Dr. Frank Bumpus Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Frank J. Doherty Fordham University BG (Ret) Patrick J. Garvey H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Shirley M. Handel Vassar College Maureen Kangas Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Alex Reese Marist College Robert E. Tompkins Sr. Denise Doring VanBuren David Schuyler, -

June 30, 2011 Annual Report

Massachusetts Historical SocietyAnnual Report July 1, 2010, to June 30, 2011 Board of Trustees 2011 Officers Trustees L. Dennis Shapiro William C. Clendaniel, Chair Bernard Bailyn Joseph Peter Spang Charles C. Ames, Frederick D. Ballou Judith Bryant Wittenberg Co-Vice Chair Levin H. Campbell, Jr. Hiller B. Zobel Nancy S. Anthony, Joyce Chaplin Life Trustees Co-Vice Chair Herbert P. Dane Leo Leroy Beranek John F. Moffitt, Secretary Amalie M. Kass Henry Lee William R. Cotter, Treasurer Pauline Maier Trustees Emeriti Sheila D. Perry Nancy R. Coolidge Frederick G. Pfannenstiehl Arthur C. Hodges Lia G. Poorvu James M. Storey Byron Rushing John L. Thorndike G. West Saltonstall Council of Overseers 2011 Amalie M. Kass, Chair Deborah M. Gates Cokie B. Roberts Benjamin C. Adams Henry L. Gates Byron Rushing Robert C. Baron Bayard Henry Mary R. Saltonstall Anne F. Brooke Elizabeth B. Johnson Paul W. Sandman Levin H. Campbell, Jr. Catherine C. Lastavica James W. Segal William C. Clendaniel, Emily Lewis Anne Sternlicht ex officio George Lewis John W. Thorndike Edward S. Cooke, Jr. Janina Longtine Nicholas Thorndike Francis L. Coolidge Nathaniel D. Philbrick Alexander Webb III Daniel Coquillette George Putnam John Winthrop Contents A Message from the Chair of the Board and the President 1 July 1, 2010, to June 30, 2011: The Year in Review Collections 3 Research Activities and Services 7 Programming and Outreach 10 Development and Membership 14 Committee Members 19 Treasurer’s Report 20 Bylaws of the Massachusetts Historical Society 22 Fellows, Corresponding -

Newsmaker Light Horse Harry Lee

Newsmaker Light Horse Harry Lee Our appetite for news is insatiable. We relish instant He served in several battles, and he was present when breaking news on the television, the internet, in website, Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown to end the Revolu- blogs, videos, in books and magazines, and finally, in tionary War. Lee married his second cousin “Divine” the daily newspaper. Tell me what is going on, please! Matilda Ludwell in 1782 They had three children, Philip, Lucy and Henry IV. Matilda died in 1790. One resource that met the need for news in the 18th century America was the newspaper. Starting with the After the War, Lee served in the Continental Congress Boston Gazette in 1704, the first continuously printed until 1788. He favored adopting the Constitution. In paper, the colonists in the major east coast cities did 1791 Lee was elected Governor of Virginia. He married have newspapers that increasingly printed local as well wealthy Ann Hill Carter in 1792. They gave birth to six as news from England. In the furor surrounding the children: an unnamed infant, Charles, Anne, Sydney, Revolution War, and the need to shape political opinion, Robert Edward Lee, January 19, 1807, and Mildred. Thomas Jefferson launched the National Gazette in 1791, while Alexander Hamilton utilized The Gazette of The Pittsburgh Gazette covered the ongoing local re- the United States in his political efforts. But settlers sponse to the imposition in 1791 of a federal tax on west of the Allegheny Mountains citizens relied on word whiskey. The dramatic insurrection of farmers in the four of mouth, military dispatches and letters to know the counties around Pittsburgh on July 15 to 17, 1794 made news from the rest of the world - until July 29, 1786 the headlines. -

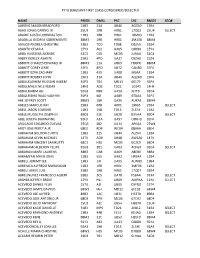

FY19 SFC AC Considered Selected.Xlsx

FY19 SERGEANT FIRST CLASS CONSIDERED/SELECTED NAME PMOS DMSL PSC UIC RMOS SEQ# AARONS MASON BRADFORD 13B3 31A UB46 AG7A0 13B4 ABAD JONAS CARINO JR 25U3 1RB HR01 17Q02 25U4 SELECT ABADIE AUSTIN JOHNDALTON 11B3 2RB HR01 18M03 11B4 ABADILLA GEORGE SOBREMONTE 88M3 1RB HR01 3M208 88M4 ABALOS ANDREA CHRISTINE 31B3 TCO TD08 DBJAA 31B4 ABANTO CESAR A 15Y3 A01 UA05 CBBB0 15Y4 ABBA HUSSEINA AKANDE 51C3 CSB MC05 JURAA 51C4 ABBEY DERECK ASANTE 25R3 4PO UA37 DSZA0 25Z4 ABBOTT CHARLES EDWARD JR 88M3 11A UB63 H96H0 88M4 ABBOTT COREY JESSE 37F3 8PO UB72 CANB0 37F4 ABBOTT EZRA ZACHARY 11B3 425 UA08 JK6AA 11B4 ABBOTT ROBERT JOHN 19K3 31A UB46 AQ2A0 19K4 ABDULKADHEM HUSSAIN HAKEM 35P3 704 MD13 00179 35P4 ABDULMALIK NILE KEDAR 14H3 ADS TD22 1D241 14H4 ABDULRAHIM ALI 92G3 P8H UA59 JS7T0 92G4 ABDULRIDHA RAAD KADHIM 35P3 66I UA89 6TDAA 35P4 ABE JEFFREY SCOTT 88M3 18H UA36 AUKA1 88M4 ABELES MARCUS RAY 25B3 6RB HR01 19605 25B4 SELECT ABELL JASON EDWARD 11B3 198 TD13 2L5FA 11B4 ABELLI RUDOLPH JOSEPH III 89D3 52E UB28 B3VAA 89D4 SELECT ABLE JOSEPH DARWAYNE 92F3 A1A UA97 C0NHD 92F4 ABOGADO EDGARDO CUEVAS 25Q3 S82 UA14 ABEAA 25W4 ABOY JOSE PERCY A JR 68E3 RDP WC04 080AA 68E4 ABRAHAM BOLDON CURTIS 11B3 325 UB44 AL2AA 11B4 ABRAHAM KEVIN MICHAEL 14T3 ADB UB48 AWZA0 14T4 ABRAHAM VINCENT SAMKUTTY 68C3 HSS MC05 0C2C0 68C4 ABRAHAMCALDERON FELIPE 92G3 301 UA03 ACFG0 92G4 SELECT ABRAHAN MARK LAURENS 38B3 CAB UA69 A8EB0 38B4 ABRAMYAN MHER JOHN 12B3 555 UA92 HFBAA 12B4 ABRELL JEREMY LEE 13B3 14I UA95 ALWB0 13B4 ABRENICA ALFREDO MARASIGAN 11B3 1RB HR01 3MF06 11B4 ABREU JORGE