SURGICAL MANAGEMENT of STONES: Tions Appear at the End of the Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Percutaneous Nephrostomy and Sclerotherapy with 96% Ethanol for the Treatment of Simple Renal Cysts: Pilot Study Mustafa Kadıhasanoğlu1, Mete Kilciler2, Özcan Atahan3

İstanbul Med J 2016; 17: 20-3 Original Article DOI: 10.5152/imj.2016.20981 Percutaneous Nephrostomy and Sclerotherapy with 96% Ethanol for the Treatment of Simple Renal Cysts: Pilot Study Mustafa Kadıhasanoğlu1, Mete Kilciler2, Özcan Atahan3 Introduction: The objectives of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of aspiration with percutaneous nephrostomy tube and sclerotherapy with 96% ethanol for simple renal cyst. Methods: Between 2011-2014, 34 patients with symptomatic renal cysts were included in the study. Mean age was 52.3±4.6 years (range, 39-72 years). The Abstract patients had only flank pain. Procedure was performed with ultrasound guidance and under fluoroscopic control. After puncture with 18 G angiography needle, guide-wire was advanced to the collecting system. An 14Fr nephrostomy catheter was then advanced over the guide wire. After taking cystography 96% ethyl alcohol was injected into the cyst and drained amount 10%. We continued daily to inject same amount of alcohol postoperatively until the drainage was less than 50 mL. 6th months and yearly follow-up were performed with ultrasound.. Results: Percutaneous access was achieved in all patients. Cysts were unilateral, single and with a mean diameter 9.1±3.2 cm (range, 7-16 cm). Median drained volume was 212 mL (200-1600 mL) and median the injected ethanol volume was 54 mL (20- 160 mL). Radiological improvement at the end of the 6th month was amount 94.1% and 91.1% at the end of the 1st year while 83.3% of patients had symptomatic decline. There was no major complication after the procedure. -

Urology 1 Cystoscopes

Urology 1 Cystoscopes 2 Urethrotomes 3 Resectoscopes 4 Uretero-Renoscopes 5 Nephroscopes 6 Lithotripsy (UreTron) 7 Laser Therapy 8 Small Caliber 9 Fluid Management 10 Accessories Richard Wolf Medical Instruments Corporation assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content of this catalog. The information contained in this catalog is provided on an “as is” basis with no guarantees of completeness, accuracy, usefulness, or timeliness, and without warranties of any kind whatsoever, expressed or implied. 1777- 02.01-1118USA Cysto-Urethroscopes 8650 E-line design CYSTOSCOPES The E-line design guarantees optimum handling and safe, fatigue-free operation as well as a wide range of possible combinations. Basic Set for Cystoscopy Cysto-urethroscope sheath, 19.5 Fr. with obturator 8650.0341 Adapter with 1 instrument port 8650.264 Insert with Albarran deflector, 2 instrument ports 8650.204 Sterile universal sealing valve (pack of 5) 4712348 Viewing obturator 8650.724 Biopsy forceps Marburg 8650.614 Grasping forceps 8650.684 PANOVIEW telescope, 0° 8650.414 PANOVIEW telescope, 70° 8650.415 Otis urethrotome 8517.00 822.31 822.13 822.31 Flexible connector 822.13 Tray 8585030 1777- 02.01-1118USA 2 PANOVIEW Telescopes Overview CYSTOSCOPES Ø Viewing direction Color code Application mm 0° blue Standard 4 8650.414 12° orange Standard 4 8654.431 Standard 4 8654.422 30° red Long sheath 4 8668.433* 70° yellow Standard 4 8650.415 * Only 25° available. 1777- 02.01-1118USA 3 Cysto-Urethroscope 8650 for telescope 4 mm, 0°, 12°, 30°, 70° and adapters CYSTOSCOPES Sheaths and obturators Adapters Sheath incl. -

Cystoscopy to Understand a Cystoscopy, It Is Helpful to Become Familiar with the Urinary System (Figure 1)

Northwestern Memorial Hospital Patient Education TESTS AND PROCEDURES Cystoscopy To understand a cystoscopy, it is helpful to become familiar with the urinary system (Figure 1). The system’s main purpose is to remove urinary waste products from your body. Urine is produced by the kidneys, moves through the ureters and is stored in the bladder. The bladder is a balloon-like organ that stores urine. The urethra is the tube that carries urine from the bladder out of your body. If you have Figure 1. Urinary system any questions or concerns, Kidneys please ask your physician or nurse. Ureters Bladder Urethra A cystoscopy is a procedure that allows your physician to look at the inside of your urethra and bladder. A telescope-like instrument called a cystoscope is passed through your urethra into your bladder. During the procedure, your physician may also do the following, as needed: ■ Remove stones from your bladder or ureters ■ Place or remove a ureteral stent ■ Insert medication into your bladder ■ Remove small pieces of tissue for testing (biopsy) from your urinary tract A cystoscopy may be done in a physician’s office or in the hospital’s operating room (OR). Your physician will discuss which option is best for you. Preparation and procedure If the test is done in the OR, you will be asked to sign a written consent. The OR procedure and any special preparation will be explained to you. There may be some discomfort during the examination. Some patients may require sedation or anesthesia. Depending on the type of medication used for your procedure, you will be told if you need to stop eating and drinking before your procedure. -

ICD-10 Coding Clinic Corner: Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Is 413.65(A)(2): Diabetes and Osteomyelitis

Issue No. 6 Volume No. 2 September 2015 New and Revised Place of Service TABLE of CONTENTS Codes for OutpatientNote Hospital from Tony New and Revised Place of Joette P. Derricks, MPA, CMPE, CHC, CPC, CSSGB Service Codes for Outpatient Joh Vice President of Regulatory Affairs & Research Hospital ..................................... 1 MiraMed Global Services ERCP with Exchange of a Common Bile Duct Stent .......... 3 Any health insurer subject to the policy. Contractor editing shall Laparoscopic Procedure: An uniform electronic claim transaction treat POS 19 and POS 22 in the Education .................................. 5 and code set standards under the same way. The definition of a Health Insurance Portability and “campus” is found in Title 42 CFR ICD-10 Coding Clinic Corner: Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) is 413.65(a)(2): Diabetes and Osteomyelitis ..... 7 required to make changes to the Campus means the physical Place of Service (POS) code from the Stars of MiraMed ...................... 8 area immediately adjacent to POS code set maintained by the the provider’s main buildings, Are You a Good Auditor? ......... 9 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid other areas and structures that Services (CMS) effective January 1, Coding Case Scenario ............. 11 are not strictly contiguous to 2016. the main buildings but are The POS code set provides setting located within 250 yards of the If you have an article information necessary to main buildings, and any other appropriately pay Medicare and areas determined on an or idea to share for The Medicaid claims. Other payers may individual case basis, by the Code , please submit to: or may not use the POS codes in the CMS regional office, to be part Dr. -

Testosterone Replacement Therapy Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Urolithiasis

World Journal of Urology (2019) 37:2737–2746 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-019-02726-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Testosterone replacement therapy is associated with an increased risk of urolithiasis Tyler R. McClintock1 · Marie‑Therese I. Valovska2 · Nicollette K. Kwon3 · Alexander P. Cole1,3 · Wei Jiang3 · Martin N. Kathrins1 · Naeem Bhojani4 · George E. Haleblian1 · Tracey Koehlmoos5 · Adil H. Haider3,6 · Shehzad Basaria7 · Quoc‑Dien Trinh1,3 Received: 16 November 2018 / Accepted: 7 March 2019 / Published online: 23 March 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose To determine whether TRT in men with hypogonadism is associated with an increased risk of urolithiasis. Methods We conducted a population-based matched cohort study utilizing data sourced from the Military Health System Data Repository (a large military-based database that includes benefciaries of the TRICARE program). This included men aged 40–64 years with no prior history of urolithiasis who received continuous TRT for a diagnosis of hypogonadism between 2006 and 2014. Eligible individuals were matched using both demographics and comorbidities to TRICARE enrollees who did not receive TRT. The primary outcome was 2-year absolute risk of a stone-related event, comparing men on TRT to non-TRT controls. Results There were 26,586 pairs in our cohort. Four hundred and eighty-two stone-related events were observed at 2 years in the non-TRT group versus 659 in the TRT group. Log-rank comparisons showed this to be a statistically signifcant dif- ference in events between the two groups (p < 0.0001). This diference was observed for topical (p < 0.0001) and injection (p = 0.004) therapy-type subgroups, though not for pellet (p = 0.27). -

What a Difference a Delay Makes! CT Urogram: a Pictorial Essay

Abdominal Radiology (2019) 44:3919–3934 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02086-0 SPECIAL SECTION : UROTHELIAL DISEASE What a diference a delay makes! CT urogram: a pictorial essay Abraham Noorbakhsh1 · Lejla Aganovic1,2 · Noushin Vahdat1,2 · Soudabeh Fazeli1 · Romy Chung1 · Fiona Cassidy1,2 Published online: 18 June 2019 © This is a U.S. Government work and not under copyright protection in the US; foreign copyright protection may apply 2019 Abstract Purpose The aim of this pictorial essay is to demonstrate several cases where the diagnosis would have been difcult or impossible without the excretory phase image of CT urography. Methods A brief discussion of CT urography technique and dose reduction is followed by several cases illustrating the utility of CT urography. Results CT urography has become the primary imaging modality for evaluation of hematuria, as well as in the staging and surveillance of urinary tract malignancies. CT urography includes a non-contrast phase and contrast-enhanced nephrographic and excretory (delayed) phases. While the three phases add to the diagnostic ability of CT urography, it also adds potential patient radiation dose. Several techniques including automatic exposure control, iterative reconstruction algorithms, higher noise tolerance, and split-bolus have been successfully used to mitigate dose. The excretory phase is timed such that the excreted contrast opacifes the urinary collecting system and allows for greater detection of flling defects or other abnormali- ties. Sixteen cases illustrating the utility of excretory phase imaging are reviewed. Conclusions Excretory phase imaging of CT urography can be an essential tool for detecting and appropriately characterizing urinary tract malignancies, renal papillary and medullary abnormalities, CT radiolucent stones, congenital abnormalities, certain chronic infammatory conditions, and perinephric collections. -

Urology Services in the ASC

Urology Services in the ASC Brad D. Lerner, MD, FACS, CASC Medical Director Summit ASC President of Chesapeake Urology Associates Chief of Urology Union Memorial Hospital Urologic Consultant NFL Baltimore Ravens Learning Objectives: Describe the numerous basic and advanced urology cases/lines of service that can be provided in an ASC setting Discuss various opportunities regarding clinical, operational and financial aspects of urology lines of service in an ASC setting Why Offer Urology Services in Your ASC? Majority of urologic surgical services are already outpatient Many urologic procedures are high volume, short duration and low cost Increasing emphasis on movement of site of service for surgical cases from hospitals and insurance carriers to ASCs There are still some case types where patients are traditionally admitted or placed in extended recovery status that can be converted to strictly outpatient status and would be suitable for an ASC Potential core of fee-for-service case types (microsurgery, aesthetics, prosthetics, etc.) Increasing Population of Those Aged 65 and Over As of 2018, it was estimated that there were 51 million persons aged 65 and over (15.63% of total population) By 2030, it is expected that there will be 72.1 million persons aged 65 and over National ASC Statistics - 2017 Urology cases represented 6% of total case mix for ASCs Urology cases were 4th in median net revenue per case (approximately $2,400) – behind Orthopedics, ENT and Podiatry Urology comprised 3% of single specialty ASCs (5th behind -

Italy and Ligurian Regional HTA Network Abstract Number: 169775

Abstract Number: 169775 Mini HTA: an effective tool for clinical governance, resource allocation and conflict management at local (Regional) level. Gaddo Flego MD, Francesco Cardinale MD, ASL Nr 4 "Chiavarese", Italy and Ligurian Regional HTA Network The Italian National Health System is centrally governed by the Ministry of Health and by Local Health Authorities (ASL) at Regional level. The Region of Liguria is divided into 5 ASL. Each ASL governs hospitals in the territory of competence. Liguria, for the government of technological innovation, approved with a formal act in 2011 (DGR 295) the creation of a Regional HTA Network in order to implement the process of Health Technology Assessment and to develop the concept of Evidence Based Medicine. The main point of the resolution is the introduction of a Mini HTA grid, that must be filled by proponents before the introduction of any technological innovation. Regional HTA Workflow Since 2011 the Ligurian Network Regional HTA Network has Organisation & Role Hospitals require innovative evaluated the following technologies through Mini devices: Director HTA grid compilation 1) Virtual Colonoscopy CAD Coordination group 2) Porcine Dermal Collagen Surgery Consists of all Professionals who Grid submission to Scientific 3) Sling for urinary incontinence may be involved in the Secretariat 4) Collagen Matrix for sutures evaluation, depending on the 5) Fixation device in surgery device to be evaluated: doctors 6) Sterilization devices with different specialisations, Analysis of quality of data 7) Implantable device for Glaucoma clinical engineers, chemists, produced in the grid, 8) Intravascular Catheter context and scientific health economists and 9) Optical Coherence Tomography literature by the Scientific 10) Pneumothorax drainage system representatives of the citizens. -

Enteroliths in a Kock Continent Ileostomy: Case Report and Review of the Literature

E200 Cases and Techniques Library (CTL) similar symptoms recurred 2 years later. A second ileoscopy showed a narrowed Enteroliths in a Kock continent ileostomy: efferent loop that was dilated by insertion case report and review of the literature of the colonoscope, with successful relief of her symptoms. Chemical analysis of one of the retrieved enteroliths revealed calcium oxalate crystals. Five cases have previously been noted in the literature Fig. 1 Schematic (●" Table 1). representation of a Kock continent The alkaline milieu of succus entericus in ileostomy. the ileum may induce the precipitation of a calcium oxalate concretion; in contrast, the acidic milieu found more proximally in the intestine enhances the solubility of calcium. The gradual precipitation of un- conjugated bile salts, calcium oxalate, and Valve calcium carbonate crystals around a nidus composed of fecal material or undigested Efferent loop fiber can lead to the formation of calcium oxalate calculi over time [5]. Endoscopy_UCTN_Code_CCL_1AD_2AJ Reservoir Competing interests: None Hadi Moattar1, Jakob Begun1,2, Timothy Florin1,2 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Mater Adult Hospital, South Brisbane, Australia The Kock continent ileostomy (KCI) was dure was done to treat ulcerative pan- 2 Mater Research, University of Queens- designed by Nik Kock, who used an intus- colitis complicated by colon cancer. She land, Translational Research Institute, suscepted ileostomy loop to create a nip- had a well-functioning KCI that she had Woolloongabba, Australia ple valve (●" Fig.1) that would not leak catheterized daily for 34 years before she and would allow ileal effluent to be evac- presented with intermittent abdominal uated with a catheter [1]. -

An Unusually Dry Story

555050 Case Report An unusually dry story Srinivas Rajagopala, Gurukiran Danigeti, Dharanipragada Subrahmanyan We present a middle-aged woman with a prior history of central nervous system (CNS) Access this article online demyelinating disorder who presented with an acute onset quadriparesis and respiratory Website: www.ijccm.org failure. The evaluation revealed distal renal tubular acidosis with hypokalemia and DOI: 10.4103/0972-5229.164808 medullary nephrocalcinosis. Weakness persisted despite potassium correction, and ongoing Quick Response Code: Abstract evaluation confi rmed recurrent CNS and long-segment spinal cord demyelination with anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies. There was no history of dry eyes or dry mouth. Anti-Sjogren’s syndrome A antigen antibodies were elevated, and there was reduced salivary fl ow on scintigraphy. Coexistent antiphospholipid antibody syndrome with inferior vena cava thrombosis was also found on evaluation. The index patient highlights several rare manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome (pSS) as the presenting features and highlights the differential diagnosis of the clinical syndromes in which pSS should be considered in the Intensive Care Unit. Keywords: Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, distal renal tubular acidosis, hypokalemic paralysis, nephrocalcinosis, neuromyelitis optica, Sjogren’s syndrome Introduction was diagnosed with postviral encephalomyelitis 3 years ago and treated with steroids with complete resolution of Primary Sjogren’s syndrome (pSS) is a relatively symptoms and signs. She had normal menstrual cycles common autoimmune disease affecting 2–3% of the adult and had one spontaneous second trimester abortion population. It is characterized by lymphocyte infi ltration 8 years ago. She had one living child and had undergone and destruction of exocrine glands. -

Diagnostic Imaging and Risk Factors Downloaded from by EERP/BIBLIOTECA CENTRAL User on 26 August 2019

ISSN 2472-1972 Nephrocalcinosis and Nephrolithiasis in X-Linked Hypophosphatemic Rickets: Diagnostic Imaging and Risk Factors Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jes/article-abstract/3/5/1053/5418933 by EERP/BIBLIOTECA CENTRAL user on 26 August 2019 Guido de Paula Colares Neto,1,2 Fernando Ide Yamauchi,3 Ronaldo Hueb Baroni,3 Marco de Andrade Bianchi,4 Andrea Cavalanti Gomes,4 Maria Cristina Chammas,4 and Regina Matsunaga Martin1,2 1Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Osteometabolic Disorders Unit, Hospital das Cl´ınicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de S~ao Paulo, 05403-900 S~ao Paulo, SP, Brazil; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Laborat´orio de Hormoniosˆ e Gen´etica Molecular (LIM/42), Hospital das Cl´ınicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de S~ao Paulo, 05403-900 S~ao Paulo, SP, Brazil; 3Department of Radiology and Oncology, Division of Radiology, Computed Tomography Unit, Hospital das Cl´ınicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de S~ao Paulo, 05403-001 S~ao Paulo, SP, Brazil; and 4Department of Radiology and Oncology, Division of Radiology, Ultrasound Unit, Hospital das Cl´ınicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de S~ao Paulo, 05403-001 S~ao Paulo, SP, Brazil ORCiD numbers: 0000-0003-3355-0386 (G. P. Colares Neto); 0000-0002-4633-3711 (F. I. Yamauchi); 0000-0001-7041-3079 (M. C. Chammas). Context: Nephrocalcinosis (NC) and nephrolithiasis (NL) are described in hypophosphatemic rickets, but data regarding their prevalence rates and the presence of metabolic risk factors in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets (XLH) are scarce. -

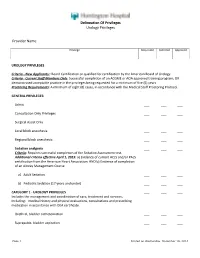

Delineation of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name

Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name: Privilege Requested Deferred Approved UROLOGY PRIVILEGES Criteria - New Applicants:: Board Certification or qualified for certification by the American Board of Urology. Criteria - Current Staff Members Only: Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA approved training program; OR demonstrated acceptable practice in the privileges being requested for a minimum of five (5) years. Proctoring Requirements: A minimum of eight (8) cases, in accordance with the Medical Staff Proctoring Protocol. GENERAL PRIVILEGES: Admit ___ ___ ___ Consultation Only Privileges ___ ___ ___ Surgical Assist Only ___ ___ ___ Local block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Regional block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Sedation analgesia ___ ___ ___ Criteria: Requires successful completion of the Sedation Assessment test. Additional criteria effective April 1, 2015: a) Evidence of current ACLS and/or PALS certification from the American Heart Association; AND b) Evidence of completion of an Airway Management Course a) Adult Sedation ___ ___ ___ b) Pediatric Sedation (17 years and under) ___ ___ ___ CATEGORY 1 - UROLOGY PRIVILEGES ___ ___ ___ Includes the management and coordination of care, treatment and services, including: medical history and physical evaluations, consultations and prescribing medication in accordance with DEA certificate. Urethral, bladder catheterization ___ ___ ___ Suprapubic, bladder aspiration ___ ___ ___ Page 1 Printed on Wednesday, December 10, 2014 Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider