Autobiography and Anecdotes by William Taswell, D.D., Sometime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

Studies in the Book of Common Prayer

Studies in the Book of Common Prayer Author(s): Luckock, Herbert Mortimer, 1833-1909 Publisher: Longmans, Green, and Co. Description: The Book of Common Prayer is the service guide used by the Catholic church for worship, sacraments, ordinations, etc. It was first written by Thomas Cranmer in 1549 under Edward VI of England. In 1881 Herbert Luckock published Studies in the Book of Common Prayer, a historical look at the evolution of the book, which has been revised and reprin- ted many times. He chronicles the Anglican Reform, Puritan Innovations, Elizabethan Reactions, and the Caroline Settle- ment with a chapter each. Luckock©s work does not discuss any of the content of The Book of Common Prayer; rather, he is concerned with discovering how the content got there. His histories are very complete and include examinations of the people, events, theology, and politics that affected the formation of the book. The accounts are meticulously re- searched and as fascinating as they are lengthy. Luckock has written many works and was a respected teacher, college president, and Dean of Lichfield Cathedral. His record of The Book of Common Prayer is a tool that should be utilized by all who are familiar with this centerpiece of Anglican worship. Abby Zwart CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: Christian Denominations Protestantism Post-Reformation Anglican Communion Church of England Liturgy and ritual i Contents Title Page 1 Dedication 2 Preface 3 Preface of the 2nd Edition 5 Introductory Chapter 6 Chapter I: The Anglican Reform 12 Chapter II: The Puritan Innovations 40 Chapter III: The Elizabethan Reaction 65 Chapter IV: The Caroline Settlement 84 Appendix I 108 Appendix II—The Order of the Communion 111 Appendix III—In the Hampton Court Conference. -

Layout 1 22/7/11 10:04 Page E

CCM 27 [9] [P]:Layout 1 22/7/11 10:04 Page e Chri Church Matters TRINITY TERM 2011 ISSUE 27 CCM 27 [9] [P]:Layout 1 22/7/11 10:02 Page b Editorial Contents ‘There are two educations; one should teach us how DEAN’S DIARY 1 to make a living and the other how to live’John Adams. CARDINAL SINS – Notes from the Archives 2 A BROAD EDUCATION – John Drury 4 “Education, education, education.” Few deny how important it is, but THE ART ROOM 5 how often do we actually stop to think what it is? In this 27th issue of Christ Church Matters two Deans define a balanced education, and REVISITING SAAKSHAR 6 members current and old illuminate the debate with stories of how they CATHEDRAL NEWS 7 fill or filled their time at the House. Pleasingly it seems that despite the increased pressures on students to gain top degrees there is still time to CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAL CHOIR – North American Tour 8 live life and attempt to fulfil all their talents. PICTURE GALLERY PATRONS’ LECTURE 10 The Dean mentions J. H. Newman. His view was that through a University THE WYCLIFFITE BIBLE – education “a habit of mind is formed which lasts through life, of which the Mishtooni Bose 11 attributes are freedom, equitableness, calmness, moderation, and wisdom. ." BOAT CLUB REPORT 12 Diversity was important to him too: "If [a student's] reading is confined simply ASSOCIATION NEWS AND EVENTS 13-26 to one subject, however such division of labour may favour the advancement of a particular pursuit . -

NP & P, Vol 2, No 2

RANDOM NORTHAMPTONSHIRE' REMINISCENCES THE Mulsos held the manor of Finedon from 'the fifteenth century till the reign of Charles II, when it descended to the two daughters of TaIifield Mulso as co-heiresses. They married two brothers, Gilbert and John Dolben, sons of the Archbishop of York, who was himself the son of the Rev. William Dolben, Rector of Stanwick. John sold his moiety of the manor to Gilbert, who was created a baronet in 1704. The baronetcy descended from father to son for 'four generations. 1 My great-grandmother was the eldest daughter of the last baronet and married the Rev. Samuel Woodfield Paul in 1806. The Vicar of Finedon, Sir Charles Cave, was an absentee, so my great-grandfather bought the family living and he and his bride were able to settle down at once in the beautiful old Vicarage-just across the lawn from the Hall-and there , they and my grandparents after them lived till 1911, when my grandfather, the Rev. George WO'odfield Paul, who was Vicar of Finedon for sixty-three years, died at the age of ninety-one. My father, l;Ierbert Woodfield Paul, had originally been the heir to the Hall; but, after he had become a Liberal at Oxford undet the influence of Asquith, Mrs. Mackworth-Dolben1 disinherited him as a matter of principle. This never affected their relations and he always remained devoted to her-as I was when I was a little boy. I was christened at Finedon by my grandfather in the church in which he had christened my father and had himself been christened by his own; and I always looked upon Finedon as my home. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 11. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/11 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1462 MACHIAVELLI, NICCOLÒ, 1469-1527 Rare 854.318 N416e 1675 The Works of the famous Nicolas Machiavel: citizen and Secretary of Florence. Written Originally in Italian, and from thence newly and faithfully Translated into English London: Printed for J.S., 1675. Description: [24], 529 [21]p. ; 32 cm. References: Wing M128. Subjects: Political science. Political ethics. War. Florence (Italy)--History. Added Author: Neville, Henry, 1620-1694, tr. Contents: -The History of florence.-The Prince.-The original of the Guelf and Ghibilin Factions.-The life of Castruccio Castracani.-The Murther of Vitelli, &c. by Duke Valentino.-The State of France.- The State of Germany.-The Marriage of Belphegor, a Novel.-Nicholas Machiavel's Letter in Vindication of Himself and His Writings. Notes: Printer's device on title-page. Title enclosed within double line rule border. Head pieces. Translated into English by Henry Neville. -

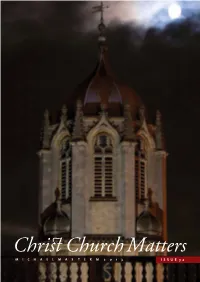

Chris Church Matters Michaelmas Term 2013 Issue 32 Editorial Contents

Chris Church Matters michaelmas TERM 2013 ISSUE 32 Editorial Contents This issue of Christ Church Matters is dominated by anniversaries and deAn’s diAry 1 departures. Martin Grossel “left” in the summer and there is a report on CArdinAl sins: Notes from the archives 2 his farewell dinner, and a fascinating article by him about the SCR on P.8. The Headmaster of the Cathedral School, Martin Bruce, and his wife “KT”, Christ ChurCh CAthedrAl Choir 4 who over the years has taken so many wonderful photographs for us, leave CAthedrAl news 6 this Christmas. The Dean leaves us in the summer of 2014, thus next year’s Christ ChurCh CAthedrAl sChool 7 Trinity issue will be his last. memories of the sCr 8 We are also losing our Development Director, Marek Kwiatkowski, in evAn morGAn: 10 February, when he joins St. Paul’s School to start up their new Development Eccentric, aristocrat and ‘Bright Young Thing’ Office. Marek has been an inspirational leader for this office, an incredible success for the House, and a good friend to many. I still cannot quite believe from sCriPtoriA to the PrintinG house 12 how many alumni really like him, even after having been subjected to A tAle of 2001 hebrew eArly Printed books 13 “the argument” and being delivered of a substantial donation. Somehow I other worlds And imAGinAry CreAtures 14 thought he would be here in perpetuity. However my commiserations go to the Old Paulines amongst you who will no doubt hear from him again soon! news 15 We also welcome new members to the Christ Church community, especially Collisions in CoAlition 16 the new Sub-Dean and Archdeacon, P.6. -

AUGUST 2018.Indd

2 3 Services & Music August 2018 Welcome from the Dean Welcome to Christ Church Cathedral, a house of learning and house of prayer, at the heart of the City of Oxford. Christ Church is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. As well as being a College, Christ Church is the Cathedral Church of the Diocese of Oxford, which covers the counties of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. First established in 1525, Christ Church is one of Oxford’s largest colleges. Its name in Latin is Ædes Christi, meaning ‘house of Christ’, and the foundation is thus sometimes known as ‘The House’. As a foundation, it is unique, comprising a College, Cathedral and Choir School – and of course a world-class Cathedral Choir, with a reputation for some of the world’s finest music. This booklet lists the music for all our services this month. You are welcome to join in the hymns – and listen to the psalms, chants and anthems – as you participate in worship with us. We hope and pray that your time here will be moving and uplifting – one of blessing and peace, and of spiritual nourishment and comfort. St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD) wrote that ‘singing belongs to one who loves’. Our prayer – for each and every one who joins us here for worship – is that in the singing and music, you will not only hear the love of God proclaimed in the beauty of worship, but will also hear something of God’s love for each and all proclaimed to you. As the Prophet Zephaniah says: ‘The LORD your God dwells with you. -

School-Days of Eminent Men. Sketches of the Progress of Education

- ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY New York State Colleges of Agriculture and Home Economics Cornell University rnel1 University Library • * »»-. -. £? LA 637.7.T58 1860 School-days of eminent men.Sketches of 3 1924 013 008 408 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013008408 SCHOOLrDAYS OF EMINENT MEN. i. SKETCHES OF THE PROGRESS OF EDUCATION IN ENGLAND, FROM THE REIGN OF KING ALFRED TO THAT OF QUEEN VICTORIA. EARLY LIVES OF CELEBRATED BRITISH AUTHORS, PHILOSO- PHERS AND POE^S, INVENTORS AND DISCOVERERS, DIVINES, ^EROES, ; STATESMEN AND JOHN TIMBS, F.S.A., iOTHoa or "ooaio£iTiE3 or London," "things not oene&au.t known," mo. KKOM THE LONDON EDITION. COLUMBUS: FOLIiETT, FOSTER AND COMPANY. MDCCOLX. I«" LA FOLLETT, FOSTER & CO., Printers, Stereotypers, Binders and Publishers, COLUMBUS , OHIO. TO THE HEADER. To our admiration of true greatness naturally succeeds some curiosity as to the means by which such distinction has been attained. The subject of " the School-days of Eminent Persons," therefore, promises an abundance of striking incident, in the early buddings of genius, and formation of character, through which may be gained glimpses of many of the hidden thoughts and secret springs by which master-minds have moved the world. The design of the present volume may be considered an ambitious one to be attempted within so limited a compass ; but I felt the incontestible facility of producing a book brimful of noble examples of human action and well-directed energy, more especially as I proposed to gather my materials from among the records of a country whose cultivated people have advanced civilization far beyond the triumphs of any nation, an- cient or modern. -

Chris Church Matters TRINITY TERM 2015 CCM CCM 35 | I CONTENTS

35 Chris Church Matters TRINITY TERM 2015 CCM CCM 35 | i CONTENTS DEAN'S DIARY 1 HALL ROOF 2 CARDINAL SINS – THE CARDINAL’S COLLEGE 4 COLLEGE NEWS 6 CATHEDRAL NEWS 8 CATHEDRAL CHOIR 9 TOWER OF LONDON POPPIES / WW1 LETTERS 10 CATHEDRAL SCHOOL 11 DEAN’S PICTURE GALLERY 12 GUISE BUST 15 LIBRARY 16 DIARY INTO UNIVERSITY 18 ASSOCIATION NEWS 19 When a purlin tumbles to the floor OVALHOUSE 28 – from the ceiling of the Dining Hall – THE ORDER OF MALTA 30 you know there will need to be some MAGNA CARTA 32 investigations. Shortly before I arrived in SIR JOHN MASTERMAN 34 the autumn, a late summer thunderstorm GARDENS 38 seems to have been the trigger for one BOOKS WITH NO ENDING 40 ancient timber to fall – from a very great height – in our beloved Hall. Fortunately, no-one was there at the time. The House slept through the storm, and awoke only to some telling debris on the floor. COVER IMAGE: Jacopo Tintoretto (1518–1594) Head of Giuliano de’ Medici, after Michelangelo. Now, not everyone knows what a purlin is. These are the support struts that connect the main roof beams, and therefore hold up We thank the following for their contribution of photographs for this edition the ceiling. They are heavy – made of oak – and exceptionally of Christ Church Matters: K.T. Bruce, Matthew Power, Dr Benjamin Spagnolo, David Stumpp, Sarah Wells, Revd Ralph Williamson. strong. But when they fall, immediate investigative and interventionist work is needed. Design and pre-press production by Baseline Arts Ltd, Oxford. -

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Christ Church 3 Senior Members’ Activities and Publications 107 The Dean 14 News from Old Members 123 The House in 2017 24 The Archives 29 Deceased Members 145 The Cathedral 31 The Cathedral Choir 35 Final Honour Schools 148 The College Chaplain 37 The Development & Graduate Degrees 153 Alumni Office 39 The Library 45 Award of University Prizes 156 The Picture Gallery 49 The Steward’s Dept. 53 Information about Gaudies 158 The Treasury 54 Tutor for Admissions 58 Other Information Junior Common Room 60 Other opportunities to stay Graduate Common Room 62 at Christ Church 160 The Boat Club 65 Conferences at Christ Commemoration Ball 67 Church 161 The Christopher Tower Publications 162 Poetry Prize 69 Cathedral Choir CDs 163 Sports Clubs 71 Sir Michael Dummett Acknowledgements 163 Lecture Theatre 75 Andrea Angel and the Silvertown Explosion 83 Obituaries Dr Paul Kent 85 Bob Jeffery 87 Prof Marilyn Adams 90 Professor David Upton 92 Dr Nabeel Qureshi 96 Sister Mary David Totah 98 Jeremy Goford 101 Geoffrey Harrison 103 1 2 CHRIST CHURCH Visitor HM THE QUEEN Dean Percy, The Very Revd Martyn William, BA Brist, MEd Sheff, PhD KCL. Canons Gorick, The Venerable Martin Charles William, MA (Cambridge), MA (Oxford) Archdeacon of Oxford Biggar, The Revd Professor Nigel John, MA PhD (Chicago), MA (Oxford), Master of Christian Studies (Regent Coll Vancouver) Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology Foot, The Revd Professor Sarah Rosamund Irvine, MA PhD (Cambridge) Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History Ward, The Revd Graham, -

Minutes (March 2014)

O X F O R D D I O C E S A N S Y N O D and B O A R D O F F I N A N C E at St Andrew’s Church, Hatters Lane, High Wycombe M I N U T E S Saturday 22 March 2014 1. OPENING WORSHIP Opening worship, on the theme of the First World War, was led by the Archdeacon of Oxford. 2. WELCOME AND NOTICES The Bishop of Oxford obtained members’ permission for guest speakers Revd Canon Dr Michael Beasley and Ms Sarah Meyrick to address the Synod, and welcomed as an observer Bishop Victoria Matthews, of Christ Church, New Zealand, a keynote speaker at the forthcoming diocesan clergy conference. Members indicated their agreement to the proposal that papers for all future meetings of the Synod should be posted in pdf format on the diocesan website (at an address to be circulated by email not later than three weeks in advance of each meeting), and that only those without email or specifically requesting it would continue to receive papers through the post, with the further option of named printed sets of papers being provided on request for collection on the day. 3. PROCLAMATION OF ACT OF SYNOD The Vacancy in See Committees Regulation 1993 as amended, as further amended by the Vacancy in See Committees (Amendment) Regulation 2013, was proclaimed as an Act of Synod. 4. MINUTES The minutes of the meeting held on Saturday 16 November 2013 were approved and signed. 5. PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS The Bishop of Oxford gave a presidential address, available on the diocesan website at http://www.oxford.anglican.org/diocesan-synod-papers. -

English Attitudes Toward Continental Protestants with Particular Reference to Church Briefs C.1680-1740

English Attitudes toward Continental Protestants with Particular Reference to Church Briefs c.1680-1740 By Sugiko Nishikawa A Dissertation for the degree of Ph. D. in the University of London 1998 B CL LO\D0 UNIV Abstract Title: English Attitudes toward Continental Protestants with Particular Reference to Church Briefs c.1680-1740 Author: Sugiko Nishikawa It has long been accepted that the Catholic threat posed by Louis X1V played an important role in English politics from the late seventeenth century onwards. The expansionist politics of Louis and his attempts to eliminate Protestants within his sphere of influence enhanced the sense of a general crisis of Protestantism in Europe. Moreover news of the persecution of foreign Protestants stimulated a great deal of anti-popish sentiment as well as a sense of the need for Protestant solidarity. The purpose of my studies is to explore how the English perceived the persecution of continental Protestants and to analyse what it meant for the English to be involved in various relief programmes for them from c. 1680 to 1740. Accordingly, I have examined the church briefs which were issued to raise contributions for the relief of continental Protestants, and which serve as evidence of Protestant internationalism against the perceived Catholic threat of the day. I have considered the spectrum of views concerning continental Protestants within the Church; in some attitudes evinced by clergymen, there was an element which might be called ecclesiastical imperialism rather than internationalism. At the same time I have examined laymen's attitudes; this investigation of the activities of the SPCK, one of the most influential voluntary societies of the day, which was closely concerned with continental Protestants, fulfills this purpose.