POLICY BRIEF a Summary of Perception Studies In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukraine Media Assessment and Program Recommendations

UKRAINE MEDIA ASSESSMENT AND PROGRAM RECOMMENDATIONS VOLUME I FINAL REPORT June 2001 USAID Contract: AEP –I-00-00-00-00018-00 Management Systems International (MSI) Programme in Comparative Media Law & Policy, Oxford University Consultants: Dennis M. Chandler Daniel De Luce Elizabeth Tucker MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS INTERNATIONAL 600 Water Street, S.W. 202/484-7170 Washington, D.C. 20024 Fax: 202/488-0754 USA TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I Acronyms and Glossary.................................................................................................................iii I. Executive Summary............................................................................................................... 1 II. Approach and Methodology .................................................................................................. 6 III. Findings.................................................................................................................................. 7 A. Overall Media Environment............................................................................................7 B. Print Media....................................................................................................................11 C. Broadcast Media............................................................................................................17 D. Internet...........................................................................................................................25 E. Business Practices .........................................................................................................26 -

Mental Health in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts - 2018

Mental health in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts - 2018 1 Content List of abbreviations....................................................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 4 2. METHODOLOGY OF THE RESEARCH ....................................................................................................... 6 3. RESUME .................................................................................................................................................. 8 4. RECOMMENDATIONS BASED ON THE FINDINGS OF THE RESEARCH .................................................. 13 5. PREVALENCE OF MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS AMONG THE PEOPLE LIVING IN DONETSK AND LUHANSK OBLASTS ...................................................................................................................................... 16 А. Detecting the traumatic experience .................................................................................................... 16 B. Prevalence of symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety disorder, excess alcohol consumption. ........ 18 C. Prevalence of mental health problems among the inner circle of the respondents .......................... 27 D. Indicators of mental well-being .......................................................................................................... 27 6. ACCESS TO ASSISTANCE WHEN SUFFERING FROM -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Hybrid Warfare and the Protection of Civilians in Ukraine

ENTERING THE GREY-ZONE: Hybrid Warfare and the Protection of Civilians in Ukraine civiliansinconflict.org i RECOGNIZE. PREVENT. PROTECT. AMEND. PROTECT. PREVENT. RECOGNIZE. Cover: June 4, 2013, Spartak, Ukraine: June 2021 Unexploded ordnances in Eastern Ukraine continue to cause harm to civilians. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] civiliansinconflict.org ORGANIZATIONAL MISSION AND VISION Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) is an international organization dedicated to promoting the protection of civilians in conflict. CIVIC envisions a world in which no civilian is harmed in conflict. Our mission is to support communities affected by conflict in their quest for protection and strengthen the resolve and capacity of armed actors to prevent and respond to civilian harm. CIVIC was established in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a young humanitarian who advocated on behalf of civilians affected by the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. Honoring Marla’s legacy, CIVIC has kept an unflinching focus on the protection of civilians in conflict. Today, CIVIC has a presence in conflict zones and key capitals throughout the world where it collaborates with civilians to bring their protection concerns directly to those in power, engages with armed actors to reduce the harm they cause to civilian populations, and advises governments and multinational bodies on how to make life-saving and lasting policy changes. CIVIC’s strength is its proven approach and record of improving protection outcomes for civilians by working directly with conflict-affected communities and armed actors. At CIVIC, we believe civilians are not “collateral damage” and civilian harm is not an unavoidable consequence of conflict—civilian harm can and must be prevented. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Donbas, Ukraine: Organizations and Activities

Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance Civil Society in Donbas, Ukraine: Organizations and Activities Volodymyr Lukichov Tymofiy Nikitiuk Liudmyla Kravchenko Luhansk oblast DONBAS DONBAS Stanytsia Donetsk Luhanska Zolote oblast Mayorske Luhansk Donetsk Maryinka Novotroitske RUSSIA Hnutove Mariupol Sea of Azov About DCAF DCAF - Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance is dedicated to improving the se- curity of people and the States they live in within a framework of democratic governance, the rule of law, and respect for human rights. DCAF contributes to making peace and de- velopment more sustainable by assisting partner states and international actors supporting them to improve the governance of their security sector through inclusive and participatory reforms. It creates innovative knowledge products, promotes norms and good practices, provides legal and policy advice and supports capacity building of both state- and non-state security sector stakeholders. Active in over 70 countries, DCAF is internationally recognized as one of the world’s leading centres of excellence for security sector governance (SSG) and security sector reform (SSR). DCAF is guided by the principles of neutrality, impartiality, local ownership, inclusive participation, and gender equality. www.dcaf.ch. Publisher DCAF - Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance P.O.Box 1360 CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland [email protected] +41 (0) 22 730 9400 Authors: Volodymyr Lukichov, Tymofiy Nikitiuk, Liudmyla Kravchenko Copy-editor: dr Grazvydas Jasutis, Richard Steyne -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 15 April 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………………. 3 I. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………. 6 A. Context B. Universal and regional human rights instruments ratified by Ukraine C. UN human rights response D. Methodology III. UNDERLYING HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS ……………………… … 10 A. Corruption and violations of economic and social rights B. Lack of accountability for human rights violations and weak rule of law institutions IV. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS RELATED TO THE MAIDAN PROTESTS ……………………………………………………… 13 A. Violations of the right to freedom of assembly B. Excessive use of force, killings, disappearances, torture and ill-treatment C. Accountability and national investigations V. CURRENT OVERALL HUMAN RIGHTS CHALLENGES ……………… 15 A. Protection of minority rights B. Freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and the right to information C. Incitement to hatred, discrimination or violence D. Lustration, judicial and security sector reforms VI. SPECIFIC HUMAN RIGHTS CHALLENGES IN CRIMEA …………….. 20 VII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ………………………….. 22 A. Conclusions B. Recommendations for immediate action C. Long-term recommendations Annex I: Concept Note for the deployment of the UN human rights monitoring mission in Ukraine 2 | P a g e I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. During March 2014 ASG Ivan Šimonović visited Ukraine twice, and travelled to Bakhchisaray, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv, Sevastopol and Simferopol, where he met with national and local authorities, Ombudspersons, civil society and other representatives, and victims of alleged human rights abuses. This report is based on his findings, also drawing on the work of the newly established United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU). -

INVESTMENT PASSPORT of Lyman Amalgamated Territorial Community the Chalk Flora Nature Reserve Contents

INVESTMENT PASSPORT of Lyman Amalgamated Territorial Community The Chalk Flora Nature Reserve Contents #1 Territory data ................................................................................................... 4 #2 Competitive advantages ................................................................................. 6 #3 Priority areas of investment ........................................................................... 7 #4 Sphere of development of the territories for the years 2019-2025 ............ 7 #5 Detailed description of the community ....................................................... 8 #6 Economic and geographical location ............................................................ 11 #7 Natural potential of the territory ................................................................. 13 #8 Territory’s economic specialization, potential directions of starting a business and favoring investments .................................................................... 18 #9 Social capital ................................................................................................... 22 #10 Housing, utilities and social infrastructure ................................................. 23 4 Investment passport of Lyman City Amalgamated Territorial Community TERRITORY #1 DATA As of June 26, 2019 Lyman ATC is in the Top-20 of the largest communities of Ukraine by population (including the communities created by administrative centers of oblasts), it ranked 19th. IN DONETSK OBLAST LYMAN ATC IS THE BIGGEST BY -

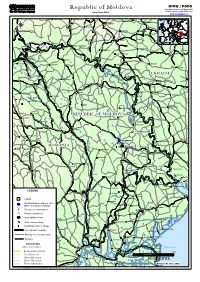

Republic of Moldova Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS Republic of Moldova Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected] ))) ))) ))) Granov ))) Zamekhov ))) Kopaygorod ))) ))) Bratslav ))) ))) Gaysin ))) Khristinovka ))) Shpikov ))) Uman !!! ))) Shargorod ))) ))) ))) Kamenets-pololskiy Tulchin ))) Ladyzhin ))) Teplik ))) Gubnik Rep_Moldova_Atlas_A3LC .wor ))) ))) ))) ))) Chernevtsy ))) Vapnyarka ))) Ternovka )) ))) Romankovtsy ))) ))) Mogilev-podolskiy ))) ))) Ocnita ))) Obodovka ))) Klembovka ))) Briceni ))) ))) Bershad ))) Goryachkovka ))) Lipkany ))) Korbul ))) Yampol ))) ))) ))) Darabani ))) Olgopol ))) Yedintsy ))) Khrustovaya ))) Soroki ))) Savran ))) Kodyma UKRAINEUKRAINE ))) UKRAINEUKRAINE ))) UKRAINEUKRAINE ))) Kamenka ))) ))) Ryshkany Voleshino ))) Balta ))) Slobodka ))) ))) Lyubashëvka ))) ))) ))) !! Rybnitsa ))) !! !! Beltsy ))) Kotovsk !! Botosani ))) Rezina ))) Ananyev ))) Bolotino ))) Corni ))) Copalau ))) ))) Lazo ))) Dolinskoye ))) Kipercheny ))) ))) Dolhasca ))) Hîrlau REPUBLICREPUBLIC OFOF MOLDOVAMOLDOVA ))) ))) Lespezi ))) Belcesti ))) Dubossary ))) Pascani ))) Ungeny !! Iasi ))) CC ))) CC DorotcaiaDorotcaia ))) CC DorotcaiaDorotcaia Holboca ))) CC ))) DorotcaiaDorotcaia ))) Halaucesti ))) Tupilati ))) Gheraesti ss ))) ss CHISINAUCHISINAU ))) ss CHISINAUCHISINAU ))) ))) ss ))) ))) CHISINAUCHISINAU ))) Velikoploskoye Chervonoznamenka ))) Codru ROMANIAROMANIA ))) ChisinauChisinau ROMANIAROMANIA ))) ROMANIAROMANIA ))) ChisinauChisinau ))) ROMANIAROMANIA ))) ROMANIAROMANIA ChisinauChisinau -

History of Russian Germans: Records of the State Archives of Odessa Region (SAOR) // Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

Published: Belousova Lilia G. History of Russian Germans: Records of the State Archives of Odessa Region (SAOR) // Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia. Archives & History. – 2004 - 3 – California Red 2011 History of Russian Germans: Records of the State Archives of Odessa Region (SAOR) By Lilia G. Belousova Lilia G. Belousova, Vice Director of the State Archives Odessa Region, helps to maintain over 100 collections containing many thousands of files about the Germans from Russia and assists hundreds of visitors from the United States to the archives. She is a graduate of Odessa State University, Department of History. The Odessa Archives: Generations of German Records The State Archives of Odessa Region (abbr. GAOO – Gosudarsvennyj Arhiv Odesskoj Oblasti) is one of the large-scale archives in the South of Ukraine, including 13,110 fonds (collections) holding 2.2 million files. Documents cover the period from the end of the eighteenth century to today. Some unique fonds reflect the history not only of Odessa and the Odessa Region but also of Southern Ukraine (former Novorossia, Black Sea Region). A large part of them refer to the history of Russian-Germans. In the pre-revolutionary period, the documents of German institutions (organizations, schools, societies, etc.) weren’t concentrated in one place because there wasn’t a joint consolidated system of state archives in Russia until 1918. Some scientists and officials tried to reform that branch. Apollon Skalkowsky, the Director of the Statistic Committee of the Novorossia Region, had an idea to create a special Archives for Southern Russia so collected valuable documents and unique papers. -

Investment Projects of Railway Transport

MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE OF UKRAINE PRIORITY INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS OF TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF UKRAINE Joint Seminar "Funding for transport infrastructure projects" Geneva, 10 September 2013 EURO-ASIAN TRANSPORT LINKS PASSING THE TERRITORY OF UKRAINE EATL Road routes Railway routes CHARACTERISTICS OF TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF UKRAINE Length of railway lines - 22 thousand km Fleet of cars: freight- 136,7 thousand units passenger - 7,4 thousand units Airports - 30, including 9 strategic Passenger Airlines– 38 Sea trade ports– 18 Private stevedore complex - 13 River ports - 11 Road carriers - 108 thousand, including 51,4 thousand – freight transportation Public roads- 169,5 thousand km, including: State significance - 21,1 thousand km Local significance - 148,4 thousand km TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT POLICY OF UKRAINE Transport Strategy of Ukraine till 2020 year (Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine from 20.10.2010 № 2174) Main directions of the Strategy: development of transport infrastructure rolling stock renewal improvement of investment climate improvement of availability and quality of transport services integration of national transport system into European and international transport systems improvement of efficiency of public administration in transport field ensuring the safety of transport processes improvement of environmental performance and energy efficiency of vehicles development of logistics centers network ECONOMIC REFORMS PROGRAM OF THE PRESIDENT OF UKRAINE FOR 2010 – 2014 (Decree of the President of Ukraine from 27.04.2011