Into Rural Drainage Within Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story Jessica K Weir

The legal outcomes the Gunditjmara achieved in the 1980s are often overlooked in the history of land rights and native title in Australia. The High Court Onus v Alcoa case and the subsequent settlement negotiated with the State of Victoria, sit alongside other well known bench marks in our land rights history, including the Gurindji strike (also known as the Wave Hill Walk-Off) and land claim that led to the development of land rights legislation in the Northern Territory. This publication links the experiences in the 1980s with the Gunditjmara’s present day recognition of native title, and considers the possibilities and limitations of native title within the broader context of land justice. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR Euphemia Day, Johnny Lovett and Amy Williams filming at Cape Jessica Weir together at the native title Bridgewater consent determination Amy Williams is an aspiring young Jessica Weir is a human geographer Indigenous film maker and the focused on ecological and social communications officer for the issues in Australia, particularly water, NTRU. Amy has recently graduated country and ecological life. Jessica with her Advanced Diploma of completed this project as part of her Media Production, and is developing Research Fellowship in the Native Title and maintaining communication Research Unit (NTRU) at the Australian strategies for the NTRU. Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR First published in 2009 by the Native Title Research Unit, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies GPO Box 553 Canberra ACT 2601 Tel: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6249 7714 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au/ Written by Jessica K Weir Copyright © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. -

Seventh Report of the Board for the Protection

APPENDIX V. DISTRIBUTION of Stores for the use of the Aborigines by the Central Board from the 1st August 1868 to 31st July 1869. Name of Station. Miscellaneous. Coranderrk 700 ft. lumber, 9 bushels lime, 2 quarts ipec. wine, 1/2-lb. tr. opium, 2 lbs. senna, 1 quart spirits turpentine, 1 lb. camphor, 2 lbs. soft soap, 8 lbs. rhubarb. 8 ozs. jalap, 1 oz. quinine, 1 pint ammonia, 12 doz. copy-books, 96 lesson books, 24 penholders, 3 boxes nibs, 1 quart ink, 12 dictionaries, 24 slates, 1 ream foolscap, 24 arithmetic books, 3 planes, 4 augers, 1 rule, 12 chisels, 3 gouges, 3 mortising chisels, 1 saw, 1 brace and bits, 2 pruning knives, 50 lbs. sago, 1000 lbs. salt, 10 lbs. hops, 36 boys' twill shirts, 150 yds. calico, 200 yds. prints, 60 yds. twill, 100 yds. osnaberg, 150 yds. holland, 100 yds, flannel, 150 yds. plaid, 100 yds. winsey, 36 doz. hooks and eyes, 2 doz. pieces tape, 2 pkgs. piping cord, 4 lbs. thread, 48 reels cotton, 200 needles, 4 lbs. candlewick, 24 tooth combs, 24 combs, 6 looking-glasses, 6 candlesticks, 6 buckets, 36 pannikins, 6 chambers, 2 pairs scissors, 24 spoons, 1 soup ladle, 36 knives and forks, 2 teapots, 2 slop pails, 6 scrubbing brushes, 2 whitewash brushes, 12 bath bricks, 2 enamelled dishes, 12 milk pans, 12 wash-hand basins, 6 washing tubs, 12 crosscut-saw files, 12 hand-saw files, 2 crosscut saws, 12 spades, 12 hoes, 12 rakes, 12 bullock bows and keys, 100 lbs. nails, 1 plough, 1 set harrows, 1 saddle and bridle, 2 sets plough harness, 6 rings for bullock yokes, 1 harness cask. -

Twenty Fifth Report of the Central Board for the Protection of The

1889. VICTORIA. TWENTY-FIFTH REPORT OF THE BOARD TOR THE PROTECTION OF THE ABORIGINES IN THE COLONY OF VICTORIA. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT BY HIS EXCELLENCY'S COMMAND By Authority: ROBT. S. BRAIN, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 129.—[!•.]—17377. Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au APPROXIMATE COST OF REPORT. Preparation— Not given, £ s. d. Printing (760 copies) ., .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 0 0 Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au REPORT. 4th November, 1889. SIR, The Board for the Protection of the Aborigines have the honour to submit for Your Excellency's consideration their Twenty-fifth Report on the condition of the Aborigines of this colony, together with the reports from the managers of the stations, and other papers. 1. The Board have held two special and eight ordinary meetings during the past year. 2. The average numbers of Aborigines and half-castes who have resided on the various stations during the year are as follow:— Coranderrk, under the management of Mr. Shaw 78 Framlingham, „ „ Mr. Goodall 90 Lake Condah, „ „ Revd. J. H. Stable 84 Lake Wellington, „ „ Revd. F. A. Hagenauer 61 Lake Tyers, „ „ Revd. John Bulmer 60 Lake Hindmarsh, „ „ Revd. P. Bogisch 48 421 Others visit the stations and reside there during short periods of the year. 3. The number of half-castes, who, under the operation of the new Act for the merging of half-castes among the general population of the colony, are earning their living with some assistance from the Board is 113. 4. Rations and clothing are still supplied to those of the half-castes who, according to the " Amended Act," satisfy the Board of their necessitous circum stances. -

Colac Otway Planning Scheme

COLAC OTWAY PLANNING SCHEME 21.07 REFERENCE DOCUMENTS 26/10/2017 C86 The following strategic studies have informed the preparation of this planning scheme. All relevant material has been included in the Scheme and decisions makers should use these documents for background research only. Material in these documents that potentially provides guidance on decision making but is not specifically referenced by the Scheme should not be given any weight. Settlement Apollo Bay Structure Plan (2007) Apollo Bay Settlement Boundary & Urban Design Review (2012) Colac Structure Plan (2007) Apollo Bay and Marengo Neighbourhood Character Review Background Report (2003) Barwon Downs Township Masterplan (2006) Beeac Township Masterplan (2001) Beech Forest Township Masterplan (2003) Birregurra and Forrest Community Infrastructure Plans (2012) Birregurra Neighbourhood Character Study (2012) Birregurra Structure Plan (2013) Carlisle River Township Masterplan (2004) Colac Otway Rural Living Strategy (2011) Cressy Township Masterplan (2007) Forrest Structure Plan (2011) Forrest Township Masterplan (2007) Gellibrand Township Masterplan (2004) Kennett River, Wye River and Separation Creek Structure Plans (2008) Lavers Hill Township Masterplan (2006) Siting and Design Guidelines for Structures on the Victorian Coast, Victorian Coastal Council (1997) Skenes Creek, Kennett River, Wye River and Separation Creek Neighbourhood Character Study (2005) Swan Marsh Township Masterplan (2001) Colac Commercial Centre Parking Precinct Plan, AECOM (2011) Colac Otway Public -

Saunders, David Proposed Museum Files Collection

Saunders, David Proposed Museum files collection MSS 260 Files on Locations/Buildings - in alphabetical order by state New South Wales Beaufort House 1946 Camperdown District – Talindert Castlecrag Challis House Commonwealth Bank Building, Annandale Footscray Government Architect Haymarket Hexham District Houses Immigrant Barracks Land Lease Homes Lismore District Homesteads – Titanga, Gala and Gnarpurt Lucerne Farm – Wallpapers Mark Foys Building – McCredie and Anderson Architects Menindee N.S.W State Government Architects – Record of an exhibition at the State Office Block 1970 Opera House Penshurst District – Kolor Sydney – Architectural Practices Sydney – FARPSA Sydney - Government House Sydney – Queen Victoria building Sydney – Tram Routes Sydney – Treasury Sydney Architects A-Z Sydney Cove – history Victoria A.N.Z Collins Street (Union Bank) Hawthorn Alfred Hospital • Buildings Ararat • City of Ballarat District Home of Henry Condell, 1843 ‘Banyule,’ Heidelberg House No. Hannover St. Fitzroy ‘Barragunda’ Cape Schanck House, The Basin, Dandenongs Bendigo House. Oakleigh, Ferntree Gully Road. Bishopscourt Housing Commission Victoria ‘Bontharambo’ • H.C.V. Concrete House, 1947, 1966 Camberwell Town Hall etc • H.C.V. Flats Carisbrooke District – Charlotte Plains, • Timber Prefabs also Baringhup ‘Illawarra,’ Toorak – House of Charles ‘The Carlton Case’ Henry James Castlemaine Kew Mental Hospital Charlton Kew: 292 Cotham Rd. House by H. Shaless, • Churches 1888. • Preservation in Kilmore ‘Charterisville’ Heidelberg Koroit Christ Church, -

P a Rk N O Te S

Great Otway National Park and Otway Forest Park Torquay to Kennett River Angahook Visitor Guide “Rugged coastlines, dramatic cliff faces, sandy beaches and rock platforms, steep forested ridges and deep valleys of tall forest and fern clad gullies embracing spectacular waterfalls all feature here. Angahook comes from the language of the Wauthaurung people, whose ancestors lived for thousands of years off the lands in the eastern areas of the Otway Ranges. Wauthaurung people continue their spiritual and physical connection here today.” -Ranger In Charge, Dale Antonysen A daily bus service between Geelong, Lorne and Wedge-tailed Apollo Bay connects with train services to Eagle. Melbourne. For timetable details call V/Line Country Information on 13 2232. The Parks provide n o t evital s homes, food and shelter for Picnicking and Camping Eagles and a Picnic opportunities abound with lovely settings huge variety of at Blanket Leaf, Sheoak, Distillery Creek, Grey other species, including 43 River and Moggs Creek, to name a few. There species only found are many beautiful places to picnic, be sure to in the Parks and plan your visit to get the most out of your day! nowhere else in There are excellent camping opportunities the world! throughout the Parks. Whether you are looking Getting out and about for a family friendly place to park your caravan or a solitary night under the stars there’s something The Parks provide a multitude of activities for to cater to every need. Please refer to the Park visitors to enjoy. Camping, fishing, horse riding, Camping Guide overleaf for further information. -

A Brief Audit of the Corangamite Groundwater Monitoring Program

A BRIEF AUDIT OF THE CORANGAMITE GROUNDWATER MONITORING PROGRAM November 2001 AGRICULTURE VICTORIA - BENDIGO CENTRE FOR LAND PROTECTION RESEARCH Monitoring Report No. 42 Ó The State of Victoria, Department of Natural Resources & Environment, 2001 Published by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Agriculture Victoria - Bendigo – Centre for Land Protection Research Cnr Midland Highway and Taylor St Epsom Vic 3551 Australia Ó The State of Victoria, Department of Natural Resources & Environment, 2001 Published by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Agriculture Victoria - Bendigo – Centre for Land Protection Research Cnr Midland Highway and Taylor St Epsom Vic 3551 Australia Website: http://www.nre.vic.gov.au/clpr The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Pillai, Mayavan A brief audit of the Corangamite groundwater monitoring program ISBN 0 7311 4989 0 1. Groundwater – Victoria – Corangamite, Lake, Region. 2. Hydrogeological surveys – Victoria – Corangamite, Lake, Region. I. Centre for Land Protection Research (Vic.). II. Title. (Series : Monitoring report (Centre for Land Protection Research) ; 42). 551.49099457 ISSN 1324 4388 This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Agriculture Victoria Bendigo - CLPR SUMMARY Across the Corangamite Salinity Region there are in the order of 580 NRE and community groundwater monitoring bores, grouped in 28 distinct monitoring networks that have progressively been established since the late 1980s. -

The Gunditjmara People in Having This Place Recognised As a Place of the Spirit, a Place of Human Technology and Ingenuity and As a Place of Resistance

Budj Bim Caring for the spirit and the people Damein Bell Manager - Lake Condah Sustainable Development Project 21 Scott Street Heywood 3304 Australia [email protected] Ms Chris Johnston Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street Brunswick 3056 Australia [email protected] Abstract: Budj Bim National Heritage Landscape represents the extraordinary triumph of the Gunditjmara people in having this place recognised as a place of the spirit, a place of human technology and ingenuity and as a place of resistance. The Gunditjmara are the Indigenous people of this part of south- western Victoria, Australia. In this landscape, more than 30 000 years ago the Gunditjmara witnessed an important creation being, reveal himself in the landscape. Budj Bim (known today as Mount Eccles) is the source of an immense lava flow which transformed the landscape. The Gunditjmara people developed this landscape by digging channels, creating ponds and wetlands and shaping an extensive aquaculture system, providing an economic basis for the development of a settled society. This paper will present the complex management planning that has gone into restoring the lake and re-establishing Gunditjmara management, reversing the tide of Australian history, and enabling the spirit of this sacred place to again be cared for. Introduction The ancestral creation-being is revealed in the landscape of south-western Victoria (Australia) at Budj Bim (Mt Eccles). At Mount Eccles the top of his head is revealed, his teeth tung att are the scoria cones. His spirit is embedded deep in this place and in the people – Gunditjmara. Listing of Budj Bim National Heritage Landscape on Australian’s new national heritage list in 2004 was an extraordinary achievement for a remarkable people. -

Lepidium Aschersonii

National Recovery Plan for the Spiny Peppercress Lepidium aschersonii Oberon Carter Prepared by Oberon Carter, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, July 2010. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74208-969-0 This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre telephone 136 186 Citation: Carter, O. -

Summary of HFNC Presidents' AGM Reports and Minutes 1958-2008

Summary of HFNC Presidents’ AGM Reports and Minutes 1958-2008 The following dot-point summaries of the Presidents‟ Reports for the Annual General Meetings (AGM) and HFNC Minutes provide a comprehensive overview of major activities undertaken and issues addressed each year. They also show the continuing projects and concerns that were current in particular years. 1959 May – President Mr Dewar Goode – report for 1958-59 Mr Goode presented the first annual report, expressing the philosophy of the HFNC: Informal friendly cooperation within the Club, with each contributing to the pool of knowledge. The need to have established National Parks within the region – the Grampians and the Glenelg River – indeed to establish a series of National Parks from the coast to the northern arid regions that could be of great importance to science, and to preserve for posterity the remnants of our lovely and fascinating natural features. To monitor and reduce the number, intensity and extent of fires that threaten native plants and animals. That the HFNC should act to ensure that important ecological areas are established under a planned program that will preserve their plant and animal wildlife and special features for the enjoyment of this and future generations. It is better and cheaper to preserve a natural feature than to try and replace it after it has been removed or destroyed. Field Naturalists are the watchdogs of the environment – our cause is indeed worthy. The Secretary/Treasurer, Mr Don Adams, presented his report. he Club has been fortunate to have distinguished speakers – Dr Smith (Director of National Parks), Dr Kneebone (presented a film on Grampian wildflowers), Mr G Thompson (Chairman of the Soil Conservation Authority), Mr B Jennings (Forests Commission of Victoria) and Mr Turner (snakes of the district). -

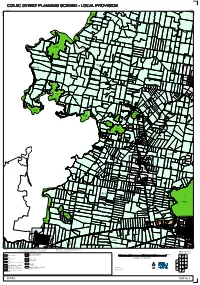

Colac Otway Planning Scheme

RD SOUTH DREEITE RD ROAD COKERILLS MORLANDS COLACCOLAC OTOTWAYWAY PLANNINGPLANNING SCHEMESCHEME -- LOCALLOCAL PROVISIONPROVISION HAYS COLACCOLAC OTOTWAYWAY PLANNINGPLANNING SCHEMESCHEME -- LOCALLOCAL PROVISIONPROVISIONROAD 5,772,000 PPRZ 5,772,000 RD CORANGAMITE RD PCRZ RD RD 709,000 725,000 RIPPONS TAITS LAKE RD BEEAC HAYS - DREEITE ROAD MORLANDS RD RD TAITS RD RD ROAD RD ROAD BEEAC RD DREEITE ROAD ROAD SOUTH RUZ PCRZ PUZ2 DUCKS ROAD ILETS SOUTH McDONALDS ROAD PATTERSONS DREEITE RD RD SOUTH DREEITE ROAD ILETS ROAD GRAHAM - WARRION SOUTH - WARRION DREEITE ENZIE RD RD RD McK LAWLORS RD RUZ RD PCRZ RD RUZ SOUTH ROAD RDZ1 RD DREEITE ROAD ROAD SCOTTS ROAD TZ WARRION ROAD FOR THIS RUZ PUZ1 WOOL WOOL CA AREA TZ RD TZ PPRZ SOUTH SEE MAPPPRZ 8 RD DREEITE READS ROAD RD RD MAHOODS ROAD ROAD RICCARTON RUZ RDZ1 RD ROAD PCRZ WARRIONWARRION ONDIT- RD RICCARTON WARRION RD O'SHEAS CORANGAMITE LAKE PUZ2 PPRZ ROAD PUZ1 PUZ6 ONDIT - WARRION TZ RD TZ ROAD ALVIE ROAD TZ RD PCRZ FARRE PCRZ LLS RD ROAD Lake PCRZ PCRZ CORANGAMITE LAKE RD PCRZ Coraguluc RD PPRZ RDZ1 PCRZ PUZ6 BAYNES ROAD BEEAC - PCRZ ROAD LAC Lake PUZ6 DORANS RD RD PCRZ BAGGOTS CORAGU Purdiguluc PPRZ TZ RD TZ CORAGULAC PUZ6 ROAD PUZ6 LINEENS RD RD RYANS RD RDZ1 BULLOCK SWAMP CORANGAMITE CORUNNUN LAKE RD RD LA RUZ TZ RD RDZ1 PUZ6 CORUNNUN TZ RD BOURKES TZ PUZ1 PPRZ Marsh COROROOKE PCRZ RUSSELL PUZ6 PUZ6 FACTORY RUZ RD FOR THIS AREARUZ RD RD SEE MAP 7 ROAD RD RDZ1 McGRATH ROAD RD BULLEENS COROROOKECOROROOKE LARPENT DELANEYS WILLISS LA BROWNS COROROOKE RD RD LA ROAD RUZ ROAD Lake ROAD RDZ1 SHEEHANS -

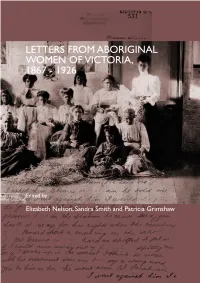

Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867-1926, Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (2002)

LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw History Department The University of Melbourne 2002 © 2002 Copyright is held on individual letters by the individual contributors or their descendants. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by The History Department The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Letters from aboriginal women in Victoria, 1867-1926. ISBN 0 7340 2160 7. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Correspondence. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Social conditions. 3. Aborigines, Australian - Government policy - Victoria. 4. Victoria - History. I. Grimshaw, Patricia, 1938- . II. Nelson, Elizabeth, 1972- . III. Smith, Sandra, 1945- . IV. University of Melbourne. Dept. of History. (Series : University of Melbourne history research series ; 11). 305.8991509945 Front cover details: ‘Raffia workers at Coranderrk’ Museum of Victoria Photographic Collection Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria Layout and cover design by Design Space TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Map 9 Introduction 11 Notes on Editors 21 The Letters: Children and family 25 Land and housing 123 Asserting personal freedom 145 Regarding missionaries and station managers 193 Religion 229 Sustenance and material assistance 239 Biographical details of the letter writers 315 Endnotes 331 Publications 357 Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867 - 1926 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We have been helped to pursue this project by many people to whom we express gratitude. Patricia Grimshaw acknowledges the University of Melbourne Small ARC Grant for the year 2000 which enabled transcripts of the letters to be made.