The Case of Puerto Rico, 18 B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922 CONSTITUTION OF THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) ACT, 1922. AN ACT TO ENACT A CONSTITUTION FOR THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) AND FOR IMPLEMENTING THE TREATY BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SIGNED AT LONDON ON THE 6TH DAY OF DECEMBER, 1921. DÁIL EIREANN sitting as a Constituent Assembly in this Provisional Parliament, acknowledging that all lawful authority comes from God to the people and in the confidence that the National life and unity of Ireland shall thus be restored, hereby proclaims the establishment of The Irish Free State (otherwise called Saorstát Eireann) and in the exercise of undoubted right, decrees and enacts as follows:— 1. The Constitution set forth in the First Schedule hereto annexed shall be the Constitution of The Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann). 2. The said Constitution shall be construed with reference to the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland set forth in the Second Schedule hereto annexed (hereinafter referred to as “the Scheduled Treaty”) which are hereby given the force of law, and if any provision of the said Constitution or of any amendment thereof or of any law made thereunder is in any respect repugnant to any of the provisions of the Scheduled Treaty, it shall, to the extent only of such repugnancy, be absolutely void and inoperative and the Parliament and the Executive Council of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) shall respectively pass such further legislation and do all such other things as may be necessary to implement the Scheduled Treaty. -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

A Case Study on the Fuerzas Armadas De Liberación Nacional (FALN)

Effects and effectiveness of law enforcement intelligence measures to counter homegrown terrorism: A case study on the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN) Final Report to the Science & Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security August 2012 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Based at the University of Maryland 3300 Symons Hall • College Park, MD 20742 • 301.405.6600 • www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The author of this report is Roberta Belli of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. Questions about this report should be directed to Dr. Belli at [email protected]. This report is part of a series sponsored by the Human Factors/Behavioral Sciences Division, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, in support of the Prevent/Deter program. The goal of this program is to sponsor research that will aid the intelligence and law enforcement communities in identifying potential terrorist threats and support policymakers in developing prevention efforts. This research was supported through Grant Award Number 2 009ST108LR0003 made to the START Consortium and the University of Maryland under principal investigator Gary LaFree. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security or START. -

Almanaque Marc Emery. June, 2009

CONTENIDOS 2CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009. Jan Susler. 6ENERO. 11 LAS FASES DE LA LUNA EN LA AGRICULTURA TRADICIONAL. José Rivera Rojas. 15 FEBRERO. 19ALIMÉNTATE CON NUESTROS SUPER ALIMENTOS SILVESTRES. María Benedetti. 25MARZO. 30EL SUEÑO DE DON PACO.Minga de Cielos. 37 ABRIL. 42EXTRACTO DE SON CIMARRÓN POR ADOLFINA VILLANUEVA. Edwin Reyes. 46PREDICCIONES Y CONSEJOS. Elsie La Gitana. 49MAYO. 53PUERTO RICO: PARAÍSO TROPICAL DE LOS TRANSGÉNICOS. Carmelo Ruiz Marrero. 57JUNIO. 62PLAZA LAS AMÉRICAS: ENSAMBLAJE DE IMÁGENES EN EL TIEMPO. Javier Román. 69JULIO. 74MACHUCA Y EL MAR. Dulce Yanomamo. 84LISTADO DE ORGANIZACIONES AMBIENTALES EN PUERTO RICO. 87AGOSTO. 1 92SOBRE LA PARTERÍA. ENTREVISTA A VANESSA CALDARI. Carolina Caycedo. 101SEPTIEMBRE. 105USANDO LAS PLANTAS Y LA NATURALEZA PARA POTENCIAR LA REVOLUCIÓN CONSCIENTE DEL PUEBLO.Marc Emery. 110OCTUBRE. 114LA GRAN MENTIRA. ENTREVISTA AL MOVIMIENTO INDÍGENA JÍBARO BORICUA.Canela Romero. 126NOVIEMBRE. 131MAPA CULTURAL DE 81 SOCIEDADES. Inglehart y Welzel. 132INFORMACIÓN Y ESTADÍSTICAS GENERALES DE PUERTO RICO. 136DICIEMBRE. 141LISTADO DE FERIAS, FESTIVALES, FIESTAS, BIENALES Y EVENTOS CULTURALES Y FOLKLÓRICOS EN PUERTO RICO Y EL MUNDO. 145CALENDARIO LUNAR Y DÍAS FESTIVOS PARA PUERTO RICO. 146ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES. 148MAPA DE PUERTO RICO EN BLANCO PARA ANOTACIONES. 2 3 CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS Febrero: Memorias torrenciales inundarán la isla en el primer aniversario de la captura de POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009 Avelino González Claudio, y en el tercer aniversario de que el FBI allanara los hogares y oficinas de independentistas y agrediera a periodistas que cubrían los eventos. Preparado por Jan Susler exclusivamente para el Almanaque Marc Emery ___________________________________________________________________ Marzo: Se predice lluvias de cartas en apoyo a la petición de libertad bajo palabra por parte de Carlos Alberto Torres. -

Ireland and Irishness: the Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity

Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity Kumar, M. S., & Scanlon, L. A. (2019). Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 109(1), 202-222. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1507812 Published in: Annals of the Association of American Geographers Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2018 by American Association of Geographers. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity The porous boundaries of postcolonial studies are put to the test in examining the Irish question and its position in postcolonial studies. Scholars have explored Ireland through the themes of decolonization, diaspora, and religion, but we propose indigenous studies as a way forward to push the boundaries and apply an appropriate context to view the 1916 Commemorations, a likely focus of Irish Studies for years to come. -

When Art Becomes Political: an Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History & Classics Undergraduate Theses History & Classics 12-15-2018 When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 Maura Wester Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Wester, Maura, "When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011" (2018). History & Classics Undergraduate Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History & Classics at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History & Classics Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 by Maura Wester HIS 490 History Honors Thesis Department of History and Classics Providence College Fall 2018 For my Mom and Dad, who encouraged a love of history and showed me what it means to be Irish-American. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………… 1 Outbreak of The Troubles, First Murals CHAPTER ONE …………………………………………………………………….. 11 1981-1989: The Hunger Strike, Republican Growth and Resilience CHAPTER TWO ……………………………………………………………………. 24 1990-1998: Peace Process and Good Friday Agreement CHAPTER THREE ………………………………………………………………… 38 The 2000s/2010s: Murals Post-Peace Agreement CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………… 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………… 63 iv 1 INTRODUCTION For nearly thirty years in the late twentieth century, sectarian violence between Irish Catholics and Ulster Protestants plagued Northern Ireland. Referred to as “the Troubles,” the violence officially lasted from 1969, when British troops were deployed to the region, until 1998, when the peace agreement, the Good Friday Agreement, was signed. -

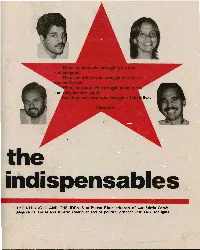

Indispensables

There are men who struggle for a day and are good There are others who struggle for a year and are better There are those who struggle many years hey are very good ^^^ m 11 th A lives These are... the indispensables THE STRUGGLE AND THE IDEALS of Puerto Rican prisoners of war Edwin Cortes, Alejandrina Torres and Alberto Rodriguez and of political prisoner Jos6 Luis Rodriguez "...all the childre the world an the reason I will i to the death to destroy colonialism... This publication is dedicated to the future of our homeland and to the children of the three new Puerto Rican Prisoners of War, Liza Beth and Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena and Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; and Noemi and Cark>s Alberto Cortes. —Alberto R Cover; prose by Bertolt Brecht Editorial El Coquf 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Chicago, Illinois 60647 OF THE 4 "...all the children of the world are the reason I will fight to the death to destroy colonialism..." This publication is dedicated to the future of our homeland and to the children of the three new Puerto Rican Prisoners of War, Liza Beth and Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena and Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; and Noemf and Carlps Alberto Cortes. —Alberto Rodriguez olt Brecht Editorial El Coqui' 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Chicago, Illinois 60647 OF THE 4 • ALBERTO RODRIGUEZ I...reaffirm the right of the Puerto Rican people to wage armed struggle against U.S. imperialism." I was born in Bronx, New York on April and we walked out. -

And Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction

Date of most recent action: October 9, 2018 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction Done: Washington, London and Moscow April 10, 1972 Opened for signature: In accordance with Article XIV, paragraph 1, the Convention was open to all States for signature until its entry into force and any State which did not sign the Convention before its entry into force may accede to it at any time. Entry into force: March 26, 1975 In accordance with Article XIV, paragraph 2, the Convention is subject to ratification by signatory States. Article XIV, paragraph 3 provides for entry into force of the Convention after the deposit of instruments of ratification by twenty-two Governments, including the Governments designated as Depositaries of the Convention [Russian Federation, United Kingdom, United States]. For States whose instruments of ratification or accession are deposited subsequent to the entry into force of the Convention, it shall enter into force on the date of deposit of their instruments of ratification or accession. Note: This status list reflects actions at Washington only. Legend: (no mark) = ratification; A = acceptance; AA = approval; a = accession; d = succession; w = withdrawal or equivalent action Participant Signature Consent to be bound Other Action Notes Afghanistan April 10, 1972 Albania June 3, 1992 a Algeria September 28, 2001 a Andorra March 2, 2015 a Angola July 26, 2016 a Argentina August 7, 1972 November 27, 1979 -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell. -

Statute of Westminster, 1931. [22 GEO

Statute of Westminster, 1931. [22 GEO. 5. CH. 4.] ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1931. Section. 1. Meaning of " Dominion" in this Act. Validity of laws made by Parliament of a Dominion. Power of Parliament of Dominion to legislate extra- territorially. 4. Parliament of United Kingdom not to legislate for Dominion except by consent. 5. Powers of Dominion Parliaments in relation to merchant shipping. 6. Powers of Dominion Parliaments in relation to Courts of Admiralty. 7. Saving for British North America Acts and application of the Act to Canada. 8. Saving for Constitution Acts of Australia and New Zealand. 9. Saving with respect to States of Australia. 10. Certain sections of Act not to apply to Australia, New Zealand or Newfoundland unless adopted. 11. Meaning of " Colony " in future Acts. 12. Short title. i [22 GEO. 5.] Statute of Westminster, 1931. [CH. 4.] CHAPTER 4. An Act to give effect to certain resolutions passed A.D. 1931. by Imperial Conferences held in the years 1926 and 1930. [11th December 1931.] HEREAS the delegates of His Majesty's Govern- W ments in the United Kingdom, the Dominion of Canada, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Dominion of New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, the Irish Free State and Newfoundland, at Imperial Conferences holden at Westminster in the years of our Lord nineteen hundred and twenty-six and nineteen hundred and thirty did concur in making the declarations and resolutions set forth in the Reports of the said Conferences : And whereas it is meet and proper to set out by way of preamble to this -

Imprescindibles

Hay hombres que ischan on y son buenos Hay otres que luchah un ano y son mejores Hay ouienss luchan muchos anos y soa muy buenos Bl s que luchan toda la vida Esos son... imprescindibles LUCHA E IDEARIO de los prisioneros de guerra puertorriquenos Edwin Cortes, Alejandrina Torres y Alberto Rodrfguez y del prisionero politico Jose Luis Rodnguez 44 P< ha destru Esta obra esta dedicada al future de nuestra patria y a los ninos de los tres nuevos Prisioneros de Guerra Puertorriquefios, Liza Beth y Catalina Torres; Yazmfn Elena y Ricardo Alberto Rodriguez; y Noerm y Carlos Alberto Cortes. Portada: pensamiento por Bertolt Brecht Editorial El Coqui 1671 N. Claremont (312) 342-8023/4 Chicago, Illinois 60647 "...todos los ninos del mundo son la razon por la cual luchare hasta la muerte para destruir el colonialismo..." —Alberto Rodrfguez AUTOBIOGRAFIAS DE LOS 4 ALBERTO RODRIGUEZ ...yo reafirmo el derecho del pueblo puertorriqueno de luchar y librar guerra contra el imperialismo estadounidense.'' Yo nacf el 14 de abril de 1953, en el de Chicago. barrio puertorriqueno conocido como el Participe en mi primer acto poli'tico a la Bronx en Nueva York. Debido a ladeprimida edad de quince anos. Los estudiantes afro- economia colonial y a la represion lanzada americanos en la escuela superior donde yo contra la clase trabajadora, mis padres, asistfa, Tilden Tech, habfan planificado una Manuel Rodriguez y Carmen Santana, habi'an huelga masiva en protesta del asesinato del sido forzados a dejar su querido Puerto Rico. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. El liderato estu- Antes de mi primer cumpleanos, mi familia diantil afro-americano habi'a pedido el apoyo se mudo de Nueva York a Chicago. -

Free Peltier?

Journal of Anti-Racist Action, Research & Education TURNINGVolume 12 Number 3 Fall 1999THE $2/newsstands TIDE In this issue: Puerto Rico*Shut Down the WTO!*ARA Mumia*Exchange on Zionism*Big Mountain*Police Brutality Free Peltier? People Against Racist Terror*PO Box 1055*Culver City 90232 310-288-5003*ISSN 1082-6491*e-mail: <[email protected]> PART'S Perspective: Puerto Rican Political Prisoners and Prisoners of War Released Que Viva Puerto Rico Libre! The forces of liberation and decolonization, and the campaign to free political emerged from prison gates for the first time in as much as 19 years. The campaign prisoners and prisoners of war held by the U.S., have won a tremendous victory. had united even Puerto Ricans who identified with commonwealth and statehood Eleven Puerto Rican political prisoners and prisoners of war were released from U.S. parties behind the demand for freedom for the independentistas. Prior to their release, prisons in September, under a conditional clemency by President Clinton. We must over 100,000 people marched in San Juan to demand that Clinton eliminate the savor the victory, and also deepen our understanding of how it was won and how it unjust and insulting conditions he was placing on their release. can be built on. An ecstatic crowd celebrated the released freedom fighters when they arrived in Edwin Cortes, Elizam Escobar, Ricardo Jimenez, Adolfo Matos, Dylcia Pagan, Puerto Rico. As TTT was going to press, the prisoners were scheduled to appear Alberto Rodriguez, Alicia Rodriguez, Ida Luz Rodriguez, Luis Rosa, Alejandrina together at a rally in Lares on September 23, commemorating the Grito de Lares, the Torres, and Carmen Valentin, were justly welcomed as heroes and patriots by the call for Puerto Rican independence from Spain.