Culture and Second Language Acquisition for Survival in Fear the Walking Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Design: Tim Osborne

MATC Offi cers President: Beth Osborne, Florida State University 1st Vice President: Chris Woodworth, Hobart and William Smith Colleges 40th 2nd Vice President/Conference Coordinator: Shawna Mefferd Kelty, ANNUAL College at Plattsburgh, Mid-America Theatre Conference State University of New York Associate Conference Coordinator: March 7-10, 2019 La Donna Forsgren, Cleveland Marriott Downtown University of Notre Dame at Key Tower Cleveland, Ohio Secretary: Jennifer Goff, Virginia Tech University Treasurer: Brian Cook, Invention University of Alaska, Anchorage Theatre History Studies, the Journal of the Mid-America Theatre Conference Editor: Sara Freeman, Conference Keynote Speakers: University of Puget Sound Tami Dixon and Jeffrey Book Review Editor: Robert B. Shimko, Carpenter, University of Houston Co-founders Bricolage Production Company Theatre/Practice: The Online Journal of the Practice/Production Symposium of MATC Theatre History Symposium Editor: Jennifer Schlueter, Respondent: The Ohio State University Amy E. Hughes, www.theatrepractice.us Brooklyn College, City University of New York Website/Listserv: Travis Stern, Bradley University Playwriting Symposium Respondent: matc.us/[email protected] Lisa Langford Graduate Student Coordinators: Sean Bartley, Florida State University Shelby Lunderman, University of Washington Program Design: Tim Osborne 3 40th Mid-America Theatre Conference Symposia Co-Chairs MATC Fellows Theatre History Symposium Arthur Ballet, 1988 Shannon Walsh, Louisiana State University Jed Davis, 1988 Heidi Nees, Bowling Green State University Patricia McIlrath, 1988 Charles Shattuck, 1990 Practice/Production Symposium Ron Engle, 1993 Karin Waidley, Kenyatta University Burnet Hobgood, 1994 Wes Pearce, University of Regina Glen Q. Pierce, 1997 Julia Curtis, 1999 Playwriting Symposium Tice Miller, 2001 Eric Thibodeaux-Thompson, University of Felicia Hardison Londré, 2002 Illinois, Springfi eld Robert A. -

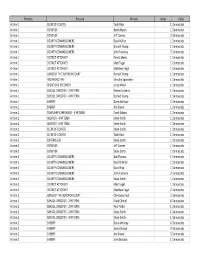

Item Box Subject Author Title Exps Pages Size Inches Pub. Date Grand

Item Box Subject Author Title Exps Pages Size Inches Pub. Date Grand Total: 3, 139, 369, 104, 343, 159, [and the 210 Namibian 51, 612, 191, 21, 44, 1, 39, 95, 428, docs so far is 2809] (2599) Central Africa:3 1 Central Africa—General Economics UNECA Subregional Strategies 19 32 8x11.5 Hints to Businessmen Visiting The London Board of 2 Central Africa—General Economics Congo (Brazzaville), Chad, Gabon 19 32 4.75x7.125 Trade and Central African Republic Purpose and Perfection Pottery as 3 Central Africa—General Art The Smithsonian Institution 3 4 8x9.25 a Woman's Art in Central Africa Botswana:139 National Institute of Access to Manual Skills Training in 1 Botswana—Bibliographies Bibliography Development and Cultural Botswana: An Annotated 9 13 8x11.5 Research Bibliography Social Thandiwe Kgosidintsi and 2 Botswana—Bibliographies Sciences—Information Publishing in Botswana 2 2 8.5x11 Neil Parsons Science National Institute of 3 Botswana—Bibliographies Bibliography Development Rearch and Working Papers 5 8 5.75x8.25 Documentation University of Botswana and Department of Library Studies 1 Botswana—Social Sciences Social Sciences 28 25 8.25x11.75 Swaziland Prospectus Social Refugees In Botswana: a Policy of 2 Botswana—Social Sciences United Nations 3 7 4.125x10.5 Sciences—Refugees Resettlement Projet De College Exterieur Du 3 Botswana—Social Sciences Social Sciences unknown 3 3 8.25x11.75 Botswana Community Relations in Botswana, with special reference to Francistown. Statement 4 Botswana—Social Sciences Social Sciences Republic of Botswana Delivered to the National Assembly 4 5 5.5x8 1971 by His Honor the Vice President Dt. -

Burns Mortuary

Page 6C East Oregonian TV TIME SUNDAY Saturday, May 7, 2016 Television > This week’s sports Television > Today’s highlights Saturday WPIX MLB Baseball N.Y. Mets at San Portland at Golden State. (Live) (2:30) Chynoweth Cup. Brandon vs. Seattle. America’s Funniest Diego. (Live) (3:00) 8:30 p.m. (2:30) 6:30 a.m. ROOT Home Videos KFFX 2:00 p.m. MLB Baseball Tampa Bay at 1:00 a.m. (11) DFL Soccer (Live) (2:00) GOLF CHAMPS Golf Final Round Seattle. (3:00) GOLF EPGA Golf Round 1 Mauritius (42) KVEW KATU 7:00 p.m. 7:00 a.m. Insperity Invitational. (Live) (2:00) Open. (2:00) Alfonso Ribeiro hosts as nine fi- USA 10:00 p.m. EPL Soccer (Live) (2:00) 3:00 p.m. TNT NBA Basketball Eastern Conference 3:00 a.m. nalists compete for a $100,000 7:30 a.m. (42) KVEW Triathlon 2015 Island House Semifi nal Game 5 Playof s. Miami at ROOT DFL Soccer B. Munich at prize in this new episode. The GOLF EPGA Golf Round 3 Trophee Invitational. (1:00) Toronto. (2:30) Ingolstadt. (2:00) Hassan II. (2:30) winner will go on to compete 3:30 p.m. Midnight 9:00 a.m. ROOT MLS Soccer San Jose at Seattle. ESPN MLB Baseball Kansas City at N.Y. Friday against the season’s earlier ESPN NCAA Softball Georgia at (2:00) Yankees. (2:00) $100,000 winner for the grand Alabama. (Live) (2:00) 10:00 a.m. 4:00 p.m. -

Write-In Results Primary 5-23-19 Municpal.Xlsx

Precinct Position WriteIn Votes Party Antrim 1 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Becky Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 CORONER Jeff Conner 2 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Forest Myers 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matt Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 DISTRICT ATTORNEY Matthew Fogal 1 Democratic Antrim 1 JUDGE OF THE SUPERIOR COURT Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 PROTHONOTARY Timothy Sponseller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 REGISTER & RECORDER Linda Miller 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 2 YR TERM Kristen Sutherin 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SCHOOL DIRECTOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Donald Trump 1 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Dane Anthony 2 Democratic Antrim 1 SHERIFF Jim Brown 1 Democratic Antrim 1 TOWNSHIP SUPERVISOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Frank Adams 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 4 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 AUDITOR ‐ 6 YR TERM Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CLERK OF COURTS Todd Rock 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CONTROLLER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Jeff Conner 1 Democratic Antrim 2 CORONER Steve Smith 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Bob Thomas 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David S Keller 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS David Slye 1 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS John Flannery 2 Democratic Antrim 2 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Steve Smith 1 Democratic -

An Ultra-Realist Analysis of the Walking Dead As Popular

CMC0010.1177/1741659017721277Crime, Media, CultureRaymen 721277research-article2017 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library Article Crime Media Culture 1 –19 Living in the end times through © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: popular culture: An ultra-realist sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659017721277DOI: 10.1177/1741659017721277 analysis of The Walking Dead as journals.sagepub.com/home/cmc popular criminology Thomas Raymen Plymouth University, UK Abstract This article provides an ultra-realist analysis of AMC’s The Walking Dead as a form of ‘popular criminology’. It is argued here that dystopian fiction such as The Walking Dead offers an opportunity for a popular criminology to address what criminologists have described as our discipline’s aetiological crisis in theorizing harmful and violent subjectivities. The social relations, conditions and subjectivities displayed in dystopian fiction are in fact an exacerbation or extrapolation of our present norms, values and subjectivities, rather than a departure from them, and there are numerous real-world criminological parallels depicted within The Walking Dead’s postapocalyptic world. As such, the show possesses a hard kernel of Truth that is of significant utility in progressing criminological theories of violence and harmful subjectivity. The article therefore explores the ideological function of dystopian fiction as the fetishistic disavowal of the dark underbelly of liberal capitalism; and views the show as an example of the ultra-realist concepts of special liberty, the criminal undertaker and the pseudopacification process in action. In drawing on these cutting- edge criminological theories, it is argued that we can use criminological analyses of popular culture to provide incisive insights into the real-world relationship between violence and capitalism, and its proliferation of harmful subjectivities. -

Fear the Walking Dead from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Fear the Walking Dead From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Fear the Walking Dead is an American horror drama television series created by Robert Kirkman and Dave Erickson[1] that premiered on AMC on August 23, 2015.[2] It is a companion series and prequel to The Walking Dead,[3] which is based Fear the Walking Dead on the comic book series of the same name by Robert Kirkman, Tony Moore, and Charlie Adlard. The first season, consisting of six episodes, aired in 2015. Its second season will comprise 15 episodes and debut on April 10, 2016.[4][5][6] Set in Los Angeles, California, the series follows a dysfunctional family composed of high school guidance counselor Madison Clark, her English teacher boyfriend Travis Manawa, her daughter Alicia, her drug-addicted son Nick, and Travis' son from a previous marriage, Chris, at the onset of the zombie apocalypse.[7][8] They must either revamp themselves or cling to their deep flaws as they come to terms with the impending collapse of civilization.[9] Genre Horror Contents Drama Created by Robert Kirkman 1 Cast and characters Dave Erickson Based on The Walking Dead 1.1 Main cast by Robert Kirkman Tony Moore 1.2 Recurring cast Charlie Adlard 2 Series overview Starring Kim Dickens 3 Production Cliff Curtis Frank Dillane 3.1 Development Alycia Debnam- Carey 3.2 Casting Elizabeth Rodriguez 3.3 Filming Mercedes Mason Lorenzo James 4 Broadcast 5 Reception Henrie Rubén Blades 5.1 Critical response Colman Domingo 5.1.1 Season 1 Theme music Atticus Ross composer 5.2 Ratings Composer(s) Paul Haslinger 5.3 Awards and nominations Country of United States origin 6 Home media Original English 7 References language(s) No. -

Fear the Walking Dead "Pilot" Written by Kirkman/Erickson

2 September 2014 fear the walking dead "pilot" written by kirkman/erickson ACT ONE UP ON: 1 INT. STASH HOUSE - BEDROOM - DAY 1 IAN BENNETT (19) was handsome once. He’s curled fetal on one of several foul mattresses in a derelict bedroom. Milky weak light penetrates threadbare curtains. The room looks like landfill. A shit bucket in the corner teems with FLIES. Ian’s in loose boxers, ribs pressed pale against blue-veined skin. He shakes with the morning chill, and his high’s wane, BELT looped around his bicep above the INJECTION SITE. He looks dead, the room his hell. There are other crates, other mattresses around him, but Ian is alone. Sole tenant. His WORKS are scattered on top of a nearby MILK CRATE -- needle, scorched spoon, Bic lighter. There’s a THUD downstairs. VOICES. Ian opens his eyes, red from broken vessels. We HOLD TIGHT on his bloody-blue orbs, pupils dilated -- until a SCREAM CURLS up from down low. Ian sits bolt upright, breathless. Three distinct BOOMING VOICES come up through the floor. Rage. Panic. Horror. Furniture CRASHES. More SCREAMS, terrified SCREAMS. Then GUNSHOTS. ONE... then ONE more. CRASHING bodies. One final, piercing SCREAM. Then silence. The silence worse. Ian shakes his head, struggles to focus against the disorient as he listens for movement, footfalls ascending the steps. He brings his knees up under him, holds -- -- then tip-toes barefoot through drug den detritus. He grabs sweats, a wife-beater -- his, someone else’s, doesn’t matter. He dresses then -- 2 INT. STASH HOUSE - SECOND FLOOR LANDING - CONTINUOUS 2 Ian pushes into the hallway, skylight overhead. -

2016-2017 President's Report

2016-2017 President’s Report o 2 MISSION STATEMENT Jesuit High School of Sacramento is a Roman Catholic college preparatory dedicated to forming competent young men as conscientious leaders in compassionate service to others for the greater glory of God. o 3 table of contents 5 Letter from the President 6 Community Spotlight 9 A Milestone Campaign 12 Annual Giving 14 Statement of Activity 18 Annual Fund 23 2017 Insignis Award 26 Alumni Annual Giving by Class 28 Cumulative Giving 34 Named Scholarships 35 Memorial & Tributes 36 Planned Giving 37 Matching Gifts 39 Commencement PLEASE NOTE: The President’s Report was compiled by the Office of Advancement to be used only for the information of Jesuit High School’s alumni, parents, and friends. The 2016-2017 President’s Report lists all new gifts and commitments to Jesuit from July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2017. Gifts made after that time will be recognized in the 2017-2018 President’s Report. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this list, but errors can occur. Please make us aware of any errors by contacting the Office for Advancement at 916.482.6060 or emailing [email protected]. “Field of Dreams” Photo Credit: Julie Mietus Photography: Jesuit’s Visual & Performing Arts 4 Department dear friends of Jesuit High School, he new year. 2018. Can you believe it! Now, I am not saying that we are perfect. TI don’t know about you, but I was just Certainly, there are other schools that inspire getting used to writing 2017 and now have their students to live exemplary lives. -

The Walking Dead

THE WALKING DEAD "Episode 105" Teleplay by Glen Mazzara PRODUCERS DRAFT - 7/03/2010 SECOND PRODUCERS DRAFT - 7/09/2010 REV. SECOND PRODUCERS DRAFT - 7/13/2010 NETWORK DRAFT - 7/14/2010 REVISED NETWORK DRAFT - 7/20/2010 Copyright © 2010 TWD Productions, LLC. All rights reserved. No portion of this script may be performed, published, sold or distributed by any means, or quoted or published in any medium including on any web site, without prior written consent. Disposal of this script 2. copy does not alter any of the restrictions set forth above. TEASER FADE IN: No clue where we are. A dark, mysterious shot: TIGHT ANGLE: The back of a MAN'S (Jenner's) head rises into shot, rimmed by top-light. He brings a breather helmet to his unseen face, slips it on over his head. As he tightens the enclosures at the back, a VOICE speaks from everywhere and nowhere, soothing and surreal: VOX Good morning, Dr. Jenner. JENNER Good morning, Vox. VOX How are you feeling this morning? JENNER A bit restless, I have to admit, Vox. A bit...well...off my game. Somewhat off-kilter. VOX That's understandable. JENNER Is it? I suppose it is. I fear I'm losing perspective on things. On what constitutes kilter versus off- kilter. VOX I sympathize. EDWIN JENNER turns to camera, his BUBBLE FACE-SHIELD kicking glare from the overhead lighting, the inside of his mask fogging badly and obscuring his face, as: JENNER Vox, you cannot sympathize. Don't patronize me, please. It messes with my head. -

Press™ Kit 01 Contents

NO SAFE HARBOUR ™ SEASON TWO ® ® PRESS™ KIT 01 CONTENTS 03 SYNOPSIS 04 CAST & CHARACTERS 23 PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES 28 INTERVIEW: DAVE ERICKSON EXECUTIVE PRODUCER & SHOWRUNNER 31 PRODUCTION CREDITS ® ™ SYNOPSIS Last season, Fear the Walking Dead explored a blended family who watched a burning, dead city as they traversed a devastated Los Angeles. In season two, the group aboard the ‘Abigail’ is unaware of the true breadth and depth of the apocalypse that surrounds them; they assume there is still a chance that some city, state, or nation might be unaffected - some place that the Infection has not reached. But as Operation Cobalt goes into full effect, the military bombs the Southland to cleanse it of the Infected, driving the Dead toward the sea. As Madison, Travis, Daniel, and their grieving families head for ports unknown, they will discover that the water may be no safer than land. ® ™ 03 CAST & CHARACTERS ® ™ 04 MADISON CLARK In many ways, the Madison of season two is the same woman we met in the pilot - a leader, a moral compass - but in a whole new devastated, apocalyptic world. As the season plays out, Madison will be faced with a world that often has no room for empathy or compassion. Forced to navigate a deceptive and manipulative chart of personalities, Madison’s success in this new world is predicated on understanding that, at the end of the world, lending a helping hand can often endanger those you love. She may maintain her maternal ferocity, but the apocalypse will force her to make decisions and sacrifices that could break even the strongest people. -

Lion's Pride Magazine

HONORING NICK CLARK Fourth National Championship Sports Hall of Fame Harvard officials visit EMCC u PG. 18 u PG. 6 u PG. 27 LIONS’ PRIDE 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Our Business and Office Technology department added new majors in Accounting Technology, Business Management Technology and Computer Technology. Those are but a few examples. We’ve grown. In January, the student union on our Golden Triangle campus opened and quickly became the hub of student activity. Construction on our “Communiversity,” which will house training to prepare students for work in today’s high-tech industries, is progressing rapidly and we are moving forward with efforts to build additional student resident halls on our Scooba campus. We’ve logged other milestones this year. Our accreditation was reaffirmed without a single follow-up report following an extensive review of our financial records, academic programs, faculty credentials and students outcomes. “Ranked among the Top 10 community colleges in the nation by SmartAsset.” Dr. Thomas Huebner, Jr. can be reached by email We were among four community colleges nationwide chosen at [email protected]. to take part in a new initiative to improve student success rates through a grant funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. East Mississippi Community College’s Scooba Through the grant, we partnered with InsideTrack, which works with colleges and universities to help increase student enrollment, campus was founded in 1927, the year Charles degree completion and career readiness. Lindberg completed the world’s first solo transatlantic flight, taking off from New York and landing safely in Paris 34 hours And we continue to garner national accolades. -

An Archaeology of Walls in the Walking Dead

Undead Divides: An Archaeology of Walls in The Walking Dead Howard Williams In 2010, the zombie horror genre gained even greater popularity than the huge following it had previously enjoyed when AMC’s The Walking Dead (TWD) first aired. The chapter surveys the archaeology of this fictional post-apocalyptic material world in the show’s seasons 1–9, focusing on its mural practices and environments which draw upon ancient, biblical, medieval and colonial motifs. The study identifies the moralities and socialities of wall-building, dividing not only survivors aspiring to re-found civilization from the wilderness and manifesting the distinctive identities of each mural community, but also distinguishing the living from the undead. The roles of the dead and the undead in mural iterations are also explored. As such, dimensions of past and present wall-building practices are reflected and inverted in this fictional world. As part of a broader ‘archaeology of The Walking Dead’, the chapter identifies the potentials of exploring the show’s physical barriers within the context of the public archaeology of frontiers and borderlands. Andrea: What’s your secret? The Governor: Really big walls. Andrea: That soldier had walls too and we all know how that turned out, so. The Governor: I guess we do. The real secret is what goes on within these walls. It’s about getting back to who we were, who we really are, not just waiting to be saved. You know people here have homes, medical care, kids go to school. Adults have jobs to do. It’s a sense of purpose.