Estimates of the Transition Zone Temperature in a Mechanically Mixed Upper Mantle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mantle Transition Zone Structure Beneath Northeast Asia from 2-D

RESEARCH ARTICLE Mantle Transition Zone Structure Beneath Northeast 10.1029/2018JB016642 Asia From 2‐D Triplicated Waveform Modeling: Key Points: • The 2‐D triplicated waveform Implication for a Segmented Stagnant Slab fi ‐ modeling reveals ne scale velocity Yujing Lai1,2 , Ling Chen1,2,3 , Tao Wang4 , and Zhongwen Zhan5 structure of the Pacific stagnant slab • High V /V ratios imply a hydrous p s 1State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and/or carbonated MTZ beneath 2 3 Northeast Asia Beijing, China, College of Earth Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, CAS Center for • A low‐velocity gap is detected within Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, Beijing, China, 4Institute of Geophysics and Geodynamics, School of Earth the stagnant slab, probably Sciences and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 5Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of suggesting a deep origin of the Technology, Pasadena, California, USA Changbaishan intraplate volcanism Supporting Information: Abstract The structure of the mantle transition zone (MTZ) in subduction zones is essential for • Supporting Information S1 understanding subduction dynamics in the deep mantle and its surface responses. We constructed the P (Vp) and SH velocity (Vs) structure images of the MTZ beneath Northeast Asia based on two‐dimensional ‐ Correspondence to: (2 D) triplicated waveform modeling. In the upper MTZ, a normal Vp but 2.5% low Vs layer compared with L. Chen and T. Wang, IASP91 are required by the triplication data. In the lower MTZ, our results show a relatively higher‐velocity [email protected]; layer (+2% V and −0.5% V compared to IASP91) with a thickness of ~140 km and length of ~1,200 km [email protected] p s atop the 660‐km discontinuity. -

STRUCTURE of EARTH S-Wave Shadow P-Wave Shadow P-Wave

STRUCTURE OF EARTH Earthquake Focus P-wave P-wave shadow shadow S-wave shadow P waves = Primary waves = Pressure waves S waves = Secondary waves = Shear waves (Don't penetrate liquids) CRUST < 50-70 km thick MANTLE = 2900 km thick OUTER CORE (Liquid) = 3200 km thick INNER CORE (Solid) = 1300 km radius. STRUCTURE OF EARTH Low Velocity Crust Zone Whole Mantle Convection Lithosphere Upper Mantle Transition Zone Layered Mantle Convection Lower Mantle S-wave P-wave CRUST : Conrad discontinuity = upper / lower crust boundary Mohorovicic discontinuity = base of Continental Crust (35-50 km continents; 6-8 km oceans) MANTLE: Lithosphere = Rigid Mantle < 100 km depth Asthenosphere = Plastic Mantle > 150 km depth Low Velocity Zone = Partially Melted, 100-150 km depth Upper Mantle < 410 km Transition Zone = 400-600 km --> Velocity increases rapidly Lower Mantle = 600 - 2900 km Outer Core (Liquid) 2900-5100 km Inner Core (Solid) 5100-6400 km Center = 6400 km UPPER MANTLE AND MAGMA GENERATION A. Composition of Earth Density of the Bulk Earth (Uncompressed) = 5.45 gm/cm3 Densities of Common Rocks: Granite = 2.55 gm/cm3 Peridotite, Eclogite = 3.2 to 3.4 gm/cm3 Basalt = 2.85 gm/cm3 Density of the CORE (estimated) = 7.2 gm/cm3 Fe-metal = 8.0 gm/cm3, Ni-metal = 8.5 gm/cm3 EARTH must contain a mix of Rock and Metal . Stony meteorites Remains of broken planets Planetary Interior Rock=Stony Meteorites ÒChondritesÓ = Olivine, Pyroxene, Metal (Fe-Ni) Metal = Fe-Ni Meteorites Core density = 7.2 gm/cm3 -- Too Light for Pure Fe-Ni Light elements = O2 (FeO) or S (FeS) B. -

Continental Flood Basalts Derived from the Hydrous Mantle Transition Zone

ARTICLE Received 4 Sep 2014 | Accepted 1 Jun 2015 | Published 14 Jul 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8700 Continental flood basalts derived from the hydrous mantle transition zone Xuan-Ce Wang1, Simon A. Wilde1, Qiu-Li Li2 & Ya-Nan Yang2 It has previously been postulated that the Earth’s hydrous mantle transition zone may play a key role in intraplate magmatism, but no confirmatory evidence has been reported. Here we demonstrate that hydrothermally altered subducted oceanic crust was involved in generating the late Cenozoic Chifeng continental flood basalts of East Asia. This study combines oxygen isotopes with conventional geochemistry to provide evidence for an origin in the hydrous mantle transition zone. These observations lead us to propose an alternative thermochemical model, whereby slab-triggered wet upwelling produces large volumes of melt that may rise from the hydrous mantle transition zone. This model explains the lack of pre-magmatic lithospheric extension or a hotspot track and also the arc-like signatures observed in some large-scale intracontinental magmas. Deep-Earth water cycling, linked to cold subduction, slab stagnation, wet mantle upwelling and assembly/breakup of supercontinents, can potentially account for the chemical diversity of many continental flood basalts. 1 ARC Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems (CCFS), The Institute for Geoscience Research (TIGeR), Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth, Western Australia 6845, Australia. 2 State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O.Box9825, Beijing 100029, China. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to X.-C.W. -

Structure of the Earth

TheThe Earth’sEarth’s StructureStructure fromfrom TravelTravel TimesTimes SphericallySpherically symmetricsymmetric structure:structure: PREMPREM --CCrustalrustal StructuStructurree --UUpperpper MantleMantle structustructurree PhasePhase transitiotransitionnss AnisotropyAnisotropy --LLowerower MantleMantle StructureStructure D”D” --SStructuretructure ofof thethe OuterOuter andand InnerInner CoreCore 3-3-DD StStructureructure ofof thethe MantleMantle fromfrom SeismicSeismic TomoTomoggrraphyaphy --UUpperpper mantlemantle -M-Miidd mmaannttllee -L-Loowweerr MMaannttllee Seismology and the Earth’s Deep Interior The Earth’s Structure SphericallySpherically SymmetricSymmetric StructureStructure ParametersParameters wwhhichich cancan bebe determineddetermined forfor aa referencereferencemodelmodel -P-P--wwaavvee v veeloloccitityy -S-S--wwaavvee v veeloloccitityy -D-Deennssitityy -A-Atttteennuuaattioionn ( (QQ)) --AAnisonisotropictropic parame parametersters -Bulk modulus K -Bulk modulus Kss --rrigidityigidity µ µ −−prepresssuresure - -ggravityravity Seismology and the Earth’s Deep Interior The Earth’s Structure PREM:PREM: velocitiesvelocities andand densitydensity PREMPREM:: PPreliminaryreliminary RReferenceeference EEartharth MMooddelel (Dziewonski(Dziewonski andand Anderson,Anderson, 1981)1981) Seismology and the Earth’s Deep Interior The Earth’s Structure PREM:PREM: AttenuationAttenuation PREMPREM:: PPreliminaryreliminary RReferenceeference EEartharth MMooddelel (Dziewonski(Dziewonski andand Anderson,Anderson, 1981)1981) Seismology and the -

The Eyes Have It

news and views flow of heat and matter in the interior2. This Irifune and Isshiki1 have shown such transition to higher pressures (as can be seen flow, in turn, drives the tectonic evolution artificial separation to be misleading by in Irifune and Isshiki’s Fig. 3 on page 704), so of the surface, including the occurrence of experimentally demonstrating Mg–Fe ex- the onset of the transition in pyrolite is post- volcanism and seismicity. change between a, b, garnet and clino- poned to greater depths relative to that in Olivine, a solid solution of forsterite pyroxene. We have known5 for some time Fo89. On the other side of the phase change, b (Mg2SiO4) and fayalite (Fe2SiO4), has the that the proportions of these minerals vary does not partition Fe into garnet as strong- a b approximate composition (Mg0.89 Fe0.11)2SiO4 with depth, as shown by the bold white lines ly as does , so is not initially Mg-enriched, (called forsterite-89 or Fo89) in samples from in Fig. 1, but Irifune and Isshiki have now and the completion of the a–b transition the shallow mantle. It transforms from the measured the accompanying variations in is not postponed relative to Fo89. The net olivine (a) phase to wadsleyite (b), changing the compositions of coexisting minerals, effect of postponing onset but not co8m- again to ringwoodite (g) at greater depths shown by the colours. In isolated Fo89 pletion is to concentrate the transition into and eventually breaking down to a mixture of olivine, mineral compositions must remain a narrower range of depths, decreasing the silicate perovskite and magnesiowüstite. -

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone Daniel J. Frost* DOI: 10.2113/GSELEMENTS.4.3.171 he upper mantle is the source of almost all magmas. It contains major body wave velocity structure, such as PREM (preliminary reference transitions in rheological and thermal behaviour that control the character Earth model) (e.g. Dziewonski and Tof plate tectonics and the style of mantle dynamics. Essential parameters Anderson 1981). in any model to describe these phenomena are the mantle’s compositional The transition zone, between 410 and thermal structure. Most samples of the mantle come from the lithosphere. and 660 km, is an excellent region Although the composition of the underlying asthenospheric mantle can be to perform such a comparison estimated, this is made difficult by the fact that this part of the mantle partially because it is free of the complex thermal and chemical structure melts and differentiates before samples ever reach the surface. The composition imparted on the shallow mantle by and conditions in the mantle at depths significantly below the lithosphere must the lithosphere and melting be interpreted from geophysical observations combined with experimental processes. It contains a number of seismic discontinuities—sharp jumps data on mineral and rock properties. Fortunately, the transition zone, which in seismic velocity, that are gener- extends from approximately 410 to 660 km, has a number of characteristic ally accepted to arise from mineral globally observed seismic properties that should ultimately place essential phase transformations (Agee 1998). These discontinuities have certain constraints on the compositional and thermal state of the mantle. features that correlate directly with characteristics of the mineral trans- KEYWORDS: seismic discontinuity, phase transformation, pyrolite, wadsleyite, ringwoodite formations, such as the proportions of the transforming minerals and the temperature at the discontinu- INTRODUCTION ity. -

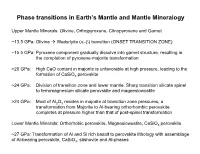

Phase Transitions in Earth's Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy

Phase transitions in Earth’s Mantle and Mantle Mineralogy Upper Mantle Minerals: Olivine, Orthopyroxene, Clinopyroxene and Garnet ~13.5 GPa: Olivine Æ Wadsrlyite (DE) transition (ONSET TRANSITION ZONE) ~15.5 GPa: Pyroxene component gradually dissolve into garnet structure, resulting in the completion of pyroxene-majorite transformation >20 GPa: High CaO content in majorite is unfavorable at high pressure, leading to the formation of CaSiO3 perovskite ~24 GPa: Division of transition zone and lower mantle. Sharp transition silicate spinel to ferromagnesium silicate perovskite and magnesiowustite >24 GPa: Most of Al2O3 resides in majorite at transition zone pressures, a transformation from Majorite to Al-bearing orthorhombic perovskite completes at pressure higher than that of post-spinel transformation Lower Mantle Minerals: Orthorhobic perovskite, Magnesiowustite, CaSiO3 perovskite ~27 GPa: Transformation of Al and Si rich basalt to perovskite lithology with assemblage of Al-bearing perovskite, CaSiO3, stishovite and Al-phases Upper Mantle: olivine, garnet and pyroxene Transition zone: olivine (a-phase) transforms to wadsleyite (b-phase) then to spinel structure (g-phase) and finally to perovskite + magnesio-wüstite. Transformations occur at P and T conditions similar to 410, 520 and 660 km seismic discontinuities Xenoliths: (mantle fragments brought to surface in lavas) 60% Olivine + 40 % Pyroxene + some garnet Images removed due to copyright considerations. Garnet: A3B2(SiO4)3 Majorite FeSiO4, (Mg,Fe)2 SiO4 Germanates (Co-, Ni- and Fe- -

Label and Describe the Earth Diagram

Name_________________________class______ Label and Describe the Earth Diagram Read the definitions then use the information to color code, label and describe IN YOUR OWN WORDS each section of the diagram below. Definitions: crust – (green) the rigid, rocky outer surface of the Earth, composed mostly of basalt and granite. The crust is the thinnest of all layers. It is thicker on continents & thinner under the oceans. inner core – (gray) the solid iron-nickel center of the Earth that is very hot and under great pressure. mantle – (orange) a rocky layer located under the crust - it is composed of silicon, oxygen, magnesium, iron, aluminum, and calcium. Convection (heat) currents carry heat from the hot inner mantle to the cooler outer mantle. outer core – (red) the molten iron-nickel layer that surrounds the inner core. ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________ Name_________________________________cLass________ Label the OUTER LAYERS of the Earth This is a cross section of only the upper layers of the Earth’s surface. Read the definitions below and use the information to locate label and describe IN TWO WORDS the outer layers of the Earth. One has been done for you. continental crust – thick, top Continental Crust – (green) the thick parts of the Earth's crust, not located under the ocean; makes up the comtinents. Oceanic Crust – (brown) thinner more dense parts of the Earth's crust located under the oceans. Ocean – (blue) large bodies of water sitting atop oceanic crust. Lithosphere– (outline in black) made of BOTH the crust plus the rigid upper part of the upper mantle. -

Time-Varying Subduction and Rollback Velocities in Slab Stagnation

Phase transformation of harzburgite and stagnant slab in the mantle transition zone Y. Zh ang 1,2, Y. Wu1, Y. Wang2, Z. Jin1, C. R. Bina3 1State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources (GPMR), China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China 2Center for Advanced Radiation Sources, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA 3Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA Subducted materials play an important role in affecting chemical composition and structure of the mantle transition zone. Harzburgite is generally accepted as an important part of subducting slabs, overlain by a layer of basalt. Seismic tomography studies have detected widespread fast anomalies in the mantle transition zone (MTZ) and lower mantle around the circum-Pacific and the Mediterranean region. These anomalies have been interpreted as stagnant oceanic lithosphere materials as these regions are closely associated with subduction zones, where the oceanic lithosphere plunges deeply into the MTZ. However, experimental studies on the phase transformations of harzburgite have been very limited, and no experimental studies have been conducted on the physical properties of harzburgite under MTZ conditions. In this study, we conducted high-temperature and high-pressure experiments, using a 1000-ton Kawai-type multi-anvil apparatus at GPMR, on a natural harzburgite at 14.1-24.2 GPa and 1473-1673 K. At 1673 K, harzburgite transformed to wadsleyite + garnet + clinopyroxene below 19 GPa and further decomposed into an assemblage of ringwoodite + garnet + stishovite above 20 GPa. Some amounts of akimotoite were produced at still higher pressures (22-23 GPa), and finally perovskite and magnesiowustite were found to coexist with garnet at 24.2 GPa. -

Geochemistry

GEOCHEMISTRY “Structure & Composition of the Earth” (M.Sc. Sem IV) Shekhar Assistant Professor Department of Geology Patna Science College Patna University E-mail: [email protected] Mob: +91-7004784271 Structure of the Earth • Earth structure and it’s composition is the essential component of Geochemistry. • Seismology is the main tool for the determination of the Earth’s interior. • Interpretation of the property is based on the behaviour of two body waves travelling within the interior. Structure of the Earth Variation in seismic body-wave paths, which in turn represents the variation in properties of the earth’s interior. Structure of the Earth Based on seismic data, Earth is broadly divided into- i. The Crust ii. The Mantle iii. The Core *Figure courtesy Geologycafe.com Density, Pressure & Temperature variation with Depth *From Bullen, An introduction to the theory of seismology. Courtesy of Cambridge Cambridge University Press *Figure courtesy Brian Mason: Principle of Geochemistry The crust • The crust is the outermost layer of the earth. • It consist 0.5-1.0 per cent of the earth’s volume and less than 1 per cent of Earth’s mass. • The average density is about “2.7 g/cm3” (average density of the earth is 5.51 g/cm³). • The crust is differentiated into- i) Oceanic crust ii) Continental crust The Oceanic crust • Covers approx. ~ 70% of the Earth’s surface area. • Average thickness ~ 6km (~4km at MOR : ~10km at volcanic plateau) • Mostly mafic in nature. • Relatively younger in age. The Oceanic crust Seismic study shows layered structural arrangement. - Seawater - Sediments - Basaltic layer - Gabbroic layer *Figure courtesy W.M.White: Geochemistry The Continental crust • Heterogeneous in nature. -

Crystal Structures of Minerals in the Lower Mantle

6 Crystal Structures of Minerals in the Lower Mantle June K. Wicks and Thomas S. Duffy ABSTRACT The crystal structures of lower mantle minerals are vital components for interpreting geophysical observations of Earth’s deep interior and in understanding the history and composition of this complex and remote region. The expected minerals in the lower mantle have been inferred from high pressure‐temperature experiments on mantle‐relevant compositions augmented by theoretical studies and observations of inclusions in natural diamonds of deep origin. While bridgmanite, ferropericlase, and CaSiO3 perovskite are expected to make up the bulk of the mineralogy in most of the lower mantle, other phases such as SiO2 polymorphs or hydrous silicates and oxides may play an important subsidiary role or may be regionally important. Here we describe the crystal structure of the key minerals expected to be found in the deep mantle and discuss some examples of the relationship between structure and chemical and physical properties of these phases. 6.1. IntrODUCTION properties of lower mantle minerals [Duffy, 2005; Mao and Mao, 2007; Shen and Wang, 2014; Ito, 2015]. Earth’s lower mantle, which spans from 660 km depth The crystal structure is the most fundamental property to the core‐mantle boundary (CMB), encompasses nearly of a mineral and is intimately related to its major physical three quarters of the mass of the bulk silicate Earth (crust and chemical characteristics, including compressibility, and mantle). Our understanding of the mineralogy and density, -

Lithospheric Strength Profiles

21 LITHOSPHERIC STRENGTH PROFILES To study the mechanical response of the lithosphere to various types of forces, one has to take into account its rheology, which means knowing how it flows. As a scientific discipline, rheology describes the interactions between strain, stress and time. Strain and stress depend on the thermal structure, the fluid content, the thickness of compositional layers and various boundary conditions. The amount of time during which the load is applied is an important factor. - At the time scale of seismic waves, up to hundreds of seconds, the sub-crustal mantle behaves elastically down deep within the asthenosphere. - Over a few to thousands of years (e.g. load of ice cap), the mantle flows like a viscous fluid. - On long geological times (more than 1 million years), the upper crust and the upper mantle behave also as thin elastic and plastic plates that overlie an inviscid (i.e. with no viscosity) substratum. The dimensionless Deborah number D, summarized as natural response time/experimental observation time, is a measure of the influence of time on flow properties. Elasticity, plastic yielding, and viscous creep are therefore ingredients of the mechanical behavior of Earth materials. Each of these three modes will be considered in assessing flow processes in the lithosphere; these mechanical attributes are expressed in terms of lithospheric strength. This strength is estimated by integrating yield stress with depth. The current state of knowledge of rock rheology is sufficient to provide broad general outlines of mechanical behavior but also has important limitations. Two very thorny problems involve the scaling of rock properties with long periods and for very large length scales.