Ornithol Sci 4: 173–177 (2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural History of Japanese Birds

Natural History of Japanese Birds Hiroyoshi Higuchi English text translated by Reiko Kurosawa HEIBONSHA 1 Copyright © 2014 by Hiroyoshi Higuchi, Reiko Kurosawa Typeset and designed by: Washisu Design Office Printed in Japan Heibonsha Limited, Publishers 3-29 Kanda Jimbocho, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 101-0051 Japan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. The English text can be downloaded from the following website for free. http://www.heibonsha.co.jp/ 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1 The natural environment and birds of Japan 6 Chapter 2 Representative birds of Japan 11 Chapter 3 Abundant varieties of forest birds and water birds 13 Chapter 4 Four seasons of the satoyama 17 Chapter 5 Active life of urban birds 20 Chapter 6 Interesting ecological behavior of birds 24 Chapter 7 Bird migration — from where to where 28 Chapter 8 The present state of Japanese birds and their future 34 3 Natural History of Japanese Birds Preface [BOOK p.3] Japan is a beautiful country. The hills and dales are covered “satoyama”. When horsetail shoots come out and violets and with rich forest green, the river waters run clear and the moun- cherry blossoms bloom in spring, birds begin to sing and get tain ranges in the distance look hazy purple, which perfectly ready for reproduction. Summer visitors also start arriving in fits a Japanese expression of “Sanshi-suimei (purple mountains Japan one after another from the tropical regions to brighten and clear waters)”, describing great natural beauty. -

Endangered Species

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Endangered species From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents For other uses, see Endangered species (disambiguation). Featured content "Endangered" redirects here. For other uses, see Endangered (disambiguation). Current events An endangered species is a species which has been categorized as likely to become Random article Conservation status extinct . Endangered (EN), as categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Donate to Wikipedia by IUCN Red List category Wikipedia store Nature (IUCN) Red List, is the second most severe conservation status for wild populations in the IUCN's schema after Critically Endangered (CR). Interaction In 2012, the IUCN Red List featured 3079 animal and 2655 plant species as endangered (EN) Help worldwide.[1] The figures for 1998 were, respectively, 1102 and 1197. About Wikipedia Community portal Many nations have laws that protect conservation-reliant species: for example, forbidding Recent changes hunting , restricting land development or creating preserves. Population numbers, trends and Contact page species' conservation status can be found in the lists of organisms by population. Tools Extinct Contents [hide] What links here Extinct (EX) (list) 1 Conservation status Related changes Extinct in the Wild (EW) (list) 2 IUCN Red List Upload file [7] Threatened Special pages 2.1 Criteria for 'Endangered (EN)' Critically Endangered (CR) (list) Permanent link 3 Endangered species in the United -

Report of the Independent Bird Survey, Bijarim Ro, Jeju, June 2019

Report of the Independent Bird Survey, Bijarim Ro, Jeju, June 2019 th Nial Moores, Birds Korea, June 24 2019 Photo 1. Black Paradise Flycatcher, Bijarim Ro, June 2019 © Ha Jungmoon 1. Survey Key Findings In the context of national obligations to the Convention on Biological Diversity; and in the recognition of the poor quality of the original assessment in June 2014 which found only 16 bird species in total and concluded that the proposed road-widening would cause an “insignificant” impact to wildlife and no impact to Endangered species (because there are no Endangered animal species in the area), this independent bird survey conducted on June 10th and 11th and again from June 14th-19th 2019 concludes that forested habitat along the Bijarim Ro is of high national and probably of high international value to avian biodiversity conservation. Although this survey was limited in time and scope (so that the populations of many species were likely under-recorded), and very little time was available to conduct additional research for this report and for translation (five days total), our survey findings include: (1) 46 species of bird in total, including six species of national conservation concern; (2) 13 territories of the nationally Endangered Fairy Pitta Pitta nympha and 23 territories of the nationally Endangered Black Paradise Flycatcher Terpsiphone atrocaudata within 500m of the Bijarim Ro, with several of these territories within 50m of the road; (3) Three territories of the nationally and globally Endangered Japanese Night Heron Gorsachius goisagi, at least two of which were within 500m of the Bijarim Ro. -

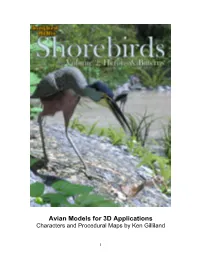

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Procedural Maps by Ken Gilliland

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Procedural Maps by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix Shorebirds Volume Two: Herons & Bitterns Contents Manual Introduction 3 Overview and Use with Poser and DAZ Studio 3 Physical-based Rendering 4 Birds in Flight 4 Pose Tips 5 Where to Find your Birds and Poses 6 Field Guide List of Species 7 Herons Great Blue Heron 8 Grey Heron 10 Little Blue Heron 12 Green Heron 14 Black-crowned Night Heron 16 Bare-throated Tiger Heron 18 Purple Heron 19 Chinese Pond Heron 21 Japanese Night Heron 22 Bitterns American Bittern 24 Eurasian Bittern 25 Australasian Bittern 27 Little Bittern 28 Yellow Bittern 30 Resources, Credits and Thanks 32 Copyrighted 2009-19 by Ken Gilliland www.songbirdremix.com Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher. 2 Songbird ReMix Shorebirds Volume Two: Herons & Bitterns Introduction “Herons and Bitterns” are birds commonly found along shorelines and mudflats. This set features such herons as the majestic Great Blue Heron, the secretive Green Heron, the endangered Japanese Night Heron and the exotic Bare-throated Tiger Heron of the Yucatan. Also included are many of the common Bitterns from around the world. Overview and Use The set is located within the Animals : Songbird ReMix folder. Here is where you will find a number of folders, such as Bird Library, Manuals and Resources . Let's look at what is contained in these folders: o Bird Library: This folder holds the actual species and poses for the "premade" birds. -

Systematics and Evolutionary Rela Tionships Among the Herons (~Rdeidae)

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 150 Systematics and Evolutionary Rela tionships Among the Herons (~rdeidae) BY ROBERT B. PAYNE and CHRISTOPHER J. RISLEY Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN August 13, 1976 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN FRANCIS C. EVANS, EDITOR The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum techniques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109. MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 150 Systematics and Evolutionary Relationships Among the Herons (Ardeidae) BY ROBERT B. PAYNE and CHRISTOPHER J. RISLEY Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN August 13, 1976 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION ....................................... -

First Report of the Palau Bird Records Committee

FIRST REPORT OF THE PALAU BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE DEMEI OTOBED, ALAN R. OLSEN†, and MILANG EBERDONG, Belau National Museum, P.O. Box 666, Koror, Palau 96940 HEATHER KETEBENGANG, Palau Conservation Society, P.O. Box 1181, Koror, Palau 96940; [email protected] MANDY T. ETPISON, Etpison Museum, P.O. Box 7049, Koror, Palau 96940 H. DOUGLAS PRATT, 1205 Selwyn Lane, Cary, North Carolina 27511 GLENN H. MCKINLAY, C/55 Albert Road, Devonport, Auckland 0624, New Zealand GARY J. WILES, 521 Rogers St. SW, Olympia, Washington 98502 ERIC A. VANDERWERF, Pacific Rim Conservation, P.O. Box 61827, Honolulu, Hawaii 96839 MARK O’BRIEN, BirdLife International Pacific Regional Office, 10 MacGregor Road, Suva, Fiji RON LEIDICH, Planet Blue Kayak Tours, P.O. Box 7076, Koror, Palau 96940 UMAI BASILIUS and YALAP YALAP, Palau Conservation Society, P.O. Box 1181, Koror, Palau 96940 ABSTRACT: After compiling a historical list of 158 species of birds known to occur in Palau, the Palau Bird Records Committee accepted 10 first records of new occur- rences of bird species: the Common Pochard (Aythya ferina), Black-faced Spoonbill (Platalea minor), Chinese Pond Heron (Ardeola bacchus), White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicurus), Eurasian Curlew (Numenius arquata), Gull-billed Tern (Gelochelidon nilotica), Channel-billed Cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae), Ruddy Kingfisher (Halcyon coromanda), Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), and Isabelline Wheatear (Oenanthe isabellina). These additions bring Palau’s total list of accepted species to 168. We report Palau’s second records of the Broad-billed Sandpiper (Calidris falcinellus), Chestnut-winged Cuckoo (Clamator coromandus), Channel- billed Cuckoo, White-throated Needletail (Hirundapus caudacutus) and Oriental Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus orientalis). -

The Philippine Synthesis Report

Ecosystems and People The Philippine Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) Sub-Global Assessment Ecosystems and People: The Philippine Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) Sub-global Assessment Edited by Rodel D. Lasco Ma. Victoria O. Espaldon University of the Philippines Los Baños/ University of the Philippines World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF-Philippines) Diliman Editorial Assistant Maricel A. Tapia A contribution to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment prepared by the Philippine Sub-global Assessment Published by: Environmental Forestry Programme College of Forestry and Natural Resources University of the Philippines Los Baños In collaboration with: Department of Environment Laguna Lake and Natural Resources Development Authority Published by the Environmental Forestry Programme College of Forestry and Natural Resources University of the Philippines Los Baños College, Laguna, Philippines 4031 © Copyright 2005 by College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines Los Baños ISBN 971-547-237-0 Layout and cover design: Maricel A. Tapia This report is a contribution to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment prepared by the Philippine Sub-global Assessment Team. The report has been prepared and reviewed through a process approved by the MA Board but the report itself has not been accepted or approved by the Assessment Panel or the MA Board. CONTENTS Foreword vii Acknowledgments ix Summary for Decision Makers 1 Philippine Sub-Global Assessment: Synthesis 9 Introduction 35 Laguna Lake: Conditions and Trends 1. Overview of the Laguna Lake Basin 43 2. Laguna Lake’s Tributary River Watersheds 53 3. Water Resources 63 4. Fish 115 5. Rice 133 6. Biodiversity 151 7. Climate Change 167 8. Institutional Arrangements, Social Conflicts, and Ecosystem Trends 187 9. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Malaysia

Avibase Page 1of 23 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Malaysia 2 Number of species: 799 3 Number of endemics: 14 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of introduced species: 17 6 Date last reviewed: 2020-03-19 7 8 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Malaysia. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=my [23/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Status Update on White-Eared Night Heron Gorsachius Magnificus in South China

Bird Conservation International (2001) 11:101–111. BirdLife International 2001 Status update on White-eared Night Heron Gorsachius magnificus in South China Nycticorax magnifica Ogilvie-Grant, 1899, Ibis (7) 5: 586 JOHN R. FELLOWES, ZHOU FANG, LEE KWOK SHING, BILLY C.H. HAU, MICHAEL W.N. LAU, VICKY W.Y. LAM, LLEWELLYN YOUNGand HEINZ HAFNER Summary White-eared Night Heron Gorsachius magnificus is probably the most threatened heron species in the world, and the highest priority for heron species conservation. From 1990 to 1998, there were sightings from only six localities in the wild. There are none in captiv- ity. In 1998 a caged bird was found in a wildlife market in the city of Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China. This finding prompted a 12- month survey in 1998–1999 of both markets and potential habitats in Guangxi. Several captured birds provided direct evidence of the existence of small populations in Guangxi and Guangdong Provinces. The respective habitats were surveyed in spring 2000, with emphasis on observations at dusk. The species was seen at two locations. Although some of the captured birds came from highly degraded habitat, the best sites seemed to be in areas near extensive primary forests, with streams, rice fields and marshes. The informa- tion obtained will be used to compile a detailed Action Plan designed to prevent the extinction of the species. Introduction Since its discovery in the 1890s, there have been only a few confirmed records of White-eared Night Heron Gorsachius magnificus, from scattered localities in China and Vietnam (Styan 1902; La Touche 1913, 1917;Geeet al. -

Status Update on White-Eared Night Heron Gorsachius Title Magnificus in South China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Status update on White-eared Night Heron Gorsachius Title magnificus in South China Fellowes, JR; Fang, Z; Kwok Shing, LEE; Hau, BCH; Lau, MWN; Author(s) Lam, VWY; Young, L; Hafner, H Citation Bird Conservation International, 2001, v. 11 n. 2, p. 101-111 Issued Date 2001 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/42099 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License Bird Conservation International (2001) 11:101–111. BirdLife International 2001 Status update on White-eared Night Heron Gorsachius magnificus in South China Nycticorax magnifica Ogilvie-Grant, 1899, Ibis (7) 5: 586 JOHN R. FELLOWES, ZHOU FANG, LEE KWOK SHING, BILLY C.H. HAU, MICHAEL W.N. LAU, VICKY W.Y. LAM, LLEWELLYN YOUNGand HEINZ HAFNER Summary White-eared Night Heron Gorsachius magnificus is probably the most threatened heron species in the world, and the highest priority for heron species conservation. From 1990 to 1998, there were sightings from only six localities in the wild. There are none in captiv- ity. In 1998 a caged bird was found in a wildlife market in the city of Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China. This finding prompted a 12- month survey in 1998–1999 of both markets and potential habitats in Guangxi. Several captured birds provided direct evidence of the existence of small populations in Guangxi and Guangdong Provinces. The respective habitats were surveyed in spring 2000, with emphasis on observations at dusk. The species was seen at two locations. -

Avibase Page 1Of 30

Avibase Page 1of 30 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Australia 2 Description includes outlying islands (Macquarie, Norfolk, Cocos Keeling, 3 Christmas Island, etc.) 4 Number of species: 986 5 Number of endemics: 359 6 Number of breeding endemics: 8 7 Number of globally threatened species: 83 8 Number of extinct species: 6 9 Number of introduced species: 28 10 Date last reviewed: 2016-12-09 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2019. Checklist of the birds of Australia. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc- eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=au&list=ioc&format=1 [30/04/2019]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

First Breeding Record of Japanese Night Heron Gorsachius Goisagi in Korea

Ornithol Sci 9: 131–134 (2010) ORIGINAL ARTICLE First Breeding Record of Japanese Night Heron Gorsachius goisagi in Korea Hongshik OH1,#, Youngho KIM1 and Namkyu KIM2 1 Department of Science Education, Jeju National University, Jeju 690–756, Republic of Korea 2 Korea International Photo Movie Interchange Association, IdoI-dong, Jeju-si, Jeju Special Self-governing Province 690–120, Republic of Korea Abstract We studied the breeding biology of the Japanese Night Heron Gorsachius ORNITHOLOGICAL goisagi from 21 June to 2 August 2009. This species was previously considered an SCIENCE endangered endemic breeding species of southern Japan only, but was found breeding © The Ornithological Society in a valley at the bottom of Mt. Halla at Ara-dong, Jeju City, the southernmost island of Japan 2010 of Korea. This marks the first record of this species ever to be found breeding in Korea. The forested area consisted predominantly of plants such as Morus bombycis, Cryptomeria japonica, Styrax japonica, Orixa japonica, Viburnum dilatatum, and Lindera erythrocarpa. Materials for the nest were largely M. bombycis, followed by S. japonica, C. japonica, and so forth. There were three eggs in the clutch, and the brooding period lasted for 42 days. A close look into the pellets demonstrated that their main prey items were earthworms, snails, and cicadas. The results of this study represent valuable data, allowing for the mapping out of new methods for managing Gorsachius goisagis, a species currently on the brink of extinction. Key words Breeding record, Conservation, Gorsachius goisagi, Japanese Night Heron, Jeju Island The Japanese Night Heron Gorsachius goisagi a Environment of the Republic of Korea as a Class II species belonging to the Ardeidae family in the Ci- endangered species and is now under close protec- coniiformes order, resembles other night herons, but tion.