Can Rare Hawaiian Land Snails Be Saved from Extinction?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Hawaiian Tree Snail Genetics

Appendix ES-9 Introduction Recent evolutionary radiations on island chains such as the Hawaiian Islands can provide insight into evolutionary processes, such as genetic drift and adaptation (Wallace 1880, Grant and Grant 1994, Losos and Ricklefs 2009). For limited mobility species, colonization processes hold important evolutionary stories not just among islands, but within islands as well (Holland and Hadfield 2002, Parent 2012). One such radiation produced at least 91 species of Hawaiian tree snails in the endemic subfamily Achatinellinae, on at least five of the six main Hawaiian Islands: O‘ahu, Maui, Lana‘i, Moloka‘i, and Hawai‘i (Pilsbry and Cooke 1912–1914, Holland and Hadfield 2007). As simultaneous hermaphrodites with the ability to self-fertilize, colonization events among islands may have occurred via the accidental transfer of a single individual by birds (Pilsbry and Cooke 1912–1914), or via land bridges that connected Maui, Molokai, and Lanai at various points in geologic history (Price and Elliot- Fisk 2004). Early naturalists attributed speciation solely to genetic drift, noting that this subfamily was “still a youthful group in the full flower of their evolution” (Pilsbry and Cooke 1912–1914). However, as these species evolved over dramatic precipitation and temperature gradients, natural selection and adaptation may have been quite rapid as species expanded to fill unexploited niches along environmental gradients, early in this subfamily’s history. As such, species in the subfamily Achatinellinae provide an excellent system for examining both neutral and adaptive processes of evolution. Habitat loss, predation by introduced species, and over-harvesting by collectors led to the extinction of more than 50 species in the subfamily Achatinellinae, and resulted in the declaration of all remaining species in the genus Achatinella as Endangered (Hadfield and Mountain 1980; U.S. -

Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019

Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019 Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019 Contents Current Affairs Q&A – January 2019 ..................................................................................................................... 2 INDIAN AFFAIRS ............................................................................................................................................. 2 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ......................................................................................................................... 94 BANKING & FINANCE ................................................................................................................................ 109 BUSINESS & ECONOMY ............................................................................................................................ 128 AWARDS & RECOGNITIONS..................................................................................................................... 149 APPOINTMENTS & RESIGNS .................................................................................................................... 177 ACQUISITIONS & MERGERS .................................................................................................................... 200 SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 202 ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................................................................... 215 SPORTS -

Achatinella Abbreviata (O`Ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary And

Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawai`i 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu tree snail) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION.......................................................................................... 3 1.1 Reviewers....................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review:................................................................. 3 1.3 Background: .................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy......................... 4 2.2 Recovery Criteria.......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 6 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................ 10 3.1 Recommended Classification:................................................................................... -

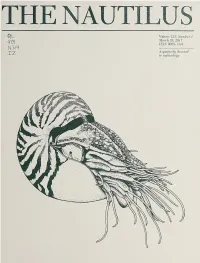

The Nautilus

THE NAUTILUS QL Volume 131, Number 1 March 28, 2017 HOI ISSN 0028-1344 N3M A quarterly devoted £2 to malacology. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Steffen Kiel Angel Valdes Jose H. Leal Department of Paleobiology Department of Malacology The Bailey-Matthews National Swedish Museum of Natural History Natural History Museum Shell Museum Box 50007 of Los Angeles County 3075 Sanibel-Captiva Road 104 05 Stockholm, SWEDEN 900 Exposition Boulevard Sanibel, FL 33957 USA Los Angeles, CA 90007 USA Harry G. Lee 4132 Ortega Forest Drive Geerat |. Vermeij EDITOR EMERITUS Jacksonville, FL 32210 USA Department of Geology University of California at Davis M. G. Harasewyeh Davis, CA 95616 USA Department of Invertebrate Zoology Charles Lydeard Biodiversity and Systematics National Museum of G. Thomas Watters Department of Biological Sciences Natural History Aquatic Ecology Laboratory University of Alabama Smithsonian Institution 1314 Kinnear Road Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 USA Washington, DC 20560 USA Columbus, OH 43212-1194 USA Bruce A. Marshall CONSULTING EDITORS Museum of New Zealand SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION Riidiger Bieler Te Papa Tongarewa Department of Invertebrates P.O. Box 467 The subscription rate for volume Field Museum of Wellington, NEW ZEALAND 131 (2017) is US $65.00 for Natural History individuals, US $102.00 for Chicago, IL 60605 USA Paula M. Mikkelsen institutions. Postage outside the Paleontological Research United States is an additional US Institution $10.00 for regular mail and US Arthur E. Bogan 1259 Trumansburg Road $28.00 for air deliver)'. All orders North Carolina State Museum of Ithaca, NY 14850 USA should be accompanied by payment Natural Sciences and sent to: THE NAUTILUS, P.O. -

Type Specimens of Hawaiian Land Snails in the Paleontological Research Institution in Ithaca, New York

Type Specimens of Hawaiian Land Snails in the Paleontological Research Institution in Ithaca, New York $XWKRUV*RXOGLQJ7ULFLD&6WURQJ(OOHQ(+D\HV.HQQHWK$ 6ODSFLQVN\-RKQ.LP-D\QHH5HWDO 6RXUFH$PHULFDQ0DODFRORJLFDO%XOOHWLQ 3XEOLVKHG%\$PHULFDQ0DODFRORJLFDO6RFLHW\ 85/KWWSVGRLRUJ %LR2QH&RPSOHWH FRPSOHWH%LR2QHRUJ LVDIXOOWH[WGDWDEDVHRIVXEVFULEHGDQGRSHQDFFHVVWLWOHV LQWKHELRORJLFDOHFRORJLFDODQGHQYLURQPHQWDOVFLHQFHVSXEOLVKHGE\QRQSURILWVRFLHWLHVDVVRFLDWLRQV PXVHXPVLQVWLWXWLRQVDQGSUHVVHV <RXUXVHRIWKLV3')WKH%LR2QH&RPSOHWHZHEVLWHDQGDOOSRVWHGDQGDVVRFLDWHGFRQWHQWLQGLFDWHV\RXU DFFHSWDQFHRI%LR2QH¶V7HUPVRI8VHDYDLODEOHDWZZZELRRQHRUJWHUPVRIXVH 8VDJHRI%LR2QH&RPSOHWHFRQWHQWLVVWULFWO\OLPLWHGWRSHUVRQDOHGXFDWLRQDODQGQRQFRPPHUFLDOXVH &RPPHUFLDOLQTXLULHVRUULJKWVDQGSHUPLVVLRQVUHTXHVWVVKRXOGEHGLUHFWHGWRWKHLQGLYLGXDOSXEOLVKHUDV FRS\ULJKWKROGHU %LR2QHVHHVVXVWDLQDEOHVFKRODUO\SXEOLVKLQJDVDQLQKHUHQWO\FROODERUDWLYHHQWHUSULVHFRQQHFWLQJDXWKRUVQRQSURILW SXEOLVKHUVDFDGHPLFLQVWLWXWLRQVUHVHDUFKOLEUDULHVDQGUHVHDUFKIXQGHUVLQWKHFRPPRQJRDORIPD[LPL]LQJDFFHVVWR FULWLFDOUHVHDUFK 'RZQORDGHG)URPKWWSVELRRQHRUJMRXUQDOV$PHULFDQ0DODFRORJLFDO%XOOHWLQRQ-XO 7erms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use $FFHVVSURYLGHGE\$PHULFDQ0DODFRORJLFDO6RFLHW\ Amer. Malac. Bull. 38(1): 1–38 (2020) Type specimens of Hawaiian land snails in the Paleontological Research Institution in Ithaca, New York Tricia C. Goulding1, Ellen E. Strong2, Kenneth A. Hayes1,2,3, John Slapcinsky4, Jaynee R. Kim1, and Norine W. Yeung1,2 1Malacology, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice St., Honolulu, Hawaii 96817, U.S.A., [email protected] -

Mgnewsletter20190206

Garden Talk Volume 8 February 6, 2019 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Plant Doctor 2 John Stephens 3 Thank YOU George 4 Soils 5 Thank you for attending the Master Gardener Annual Meeting this past Saturday. Representatives from over 22 volunteer sites were present to Events 7 talk with over 200 Master Gardeners about volunteer opportunities. MGs Opportunities 9 could also talk with members of the Advisory Committee and Speakers Bu- reau. The meeting began with a trash talk by Kemper’s Phil Egart, followed by Upcoming events: Maypop’s Tammy Behm who talked about new sustainable efforts in the re- • Feb 16 MG Book tail horticulture industry. The Annual Club Meeting and the Outreach Committees • Feb 20 Master did a great job putting the event to- Pollinator Stew- ard Program gether. Master Gardener John Lorenz took the photos. Shoenberg Theater • March 2 Pruning with Ben Nature Art • March 2—MG CE iNaturalist class • March 30 I found this little gem in Chips Tynan’s office. At Healthy Yards for first glance I thought it was a donut with purple Healthy Streams icing that had been plopped down on a piece of paper and the icing splattered. The reality is so much better. Naturalist, Bill Davit, was going to show his grandson how to open a walnut. When he opened the walnut it was filled with maggots. You and I might throw it away in disgust but not Bill. He created a circle with a bunch of poke berries, and then poured the juice of a handful of the berries onto the circle. -

9.0 Strategy for Stabilization of Koolau Achatinella Species

9-1 9.0 Strategy for Stabilization of Koolau Achatinella species General Description and Biology Achatinella species are arboreal and generally nocturnal, preferring cool and humid conditions. During the day, the snails seal themselves against leaf surfaces to avoid drying out. The snails graze on fungi growing on the surfaces of leaves and trunks. Achatinella are hermaphroditic though it is unclear whether or not individuals are capable of self-fertilization. All species in the endemic genus bear live young (USFWS 1993). Taxonomic background: The genus Achatinella is endemic to the island of Oahu and the subfamily Achatinellinae is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. A total of 41 species were recognized by Pilsbry and Cooke in a monograph of the genus (1912-1913). This treatment is still recognized for the most part by the USFWS, although several genetic studies by Holland and Hadfield (2002, 2004) have further elucidated the relationships among species. Threats: Threats to Achatinella species in general are rats (Rattus rattus, R. norvegicus, and R. exulans), predatory snails (Euglandina rosea), terrestrial flatworms Geoplana septemlineata and Platydemis manokwari, and the small terrestrial snail Oxychilus alliarius. Lower elevation sites may be under more pressure from E. rosea and rats as human disturbed sites may have provide more ingress points for these threats. Threats in the Action Area: The decline of these species has not been attributed to threats from any Army training maneuvers either direct or indirect. Rather, the decline is likely due the loss of genetic variation caused by genetic drift in the remaining small populations and predation by rats (Rattus sp.) and the introduced predatory snail Euglandina rosea. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 103. NUMBER 1 DISTRIBUTION AND VARIATION OF THE HAWAIIAN TREE SNAIL ACHATINELLA APEXFULVA DIXON IN THE KOOLAU RANGE, OAHU (With 12 Plates) BY D'ALTE A. WELCH (Publication 3684) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION DECEMBER 16, 1942 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 103, NUMBER 1 DISTRIBUTION AND VARIATION OF THE HAWAIIAN TREE SNAIL ACHATINELLA APEXFULVA DIXON IN THE KOOLAU RANGE, OAHU (With 12 Plates) BY D'ALTE A. WELCH (Publication 3684) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION DECEMBER 16, 1942 BALTIMORE, UD., 0. 8. A. DISTRIBUTION AND VARIATION OF THE HAWAIIAN TREE SNAIL ACHATINELLA APEXFULVA DIXON IN THE KOOLAU RANGE, OAHU By d'ALTE a. welch (With 12 Plates) CONTENTS Page Introduction i Scope of work i Place names of the Koolau Range 2 Climatological data and physiography g Table i. Annual precipitation records in the Koolau Range 10 Material and methods 12 Table 2. Data on material 15 Species concept 21 Taxonomy 23 Synopsis of the subspecies of Achatinclla apcxfulva Dixon 23 Group of A. a. ccstits Newcomb 28 Group of A. a. vittata Reeve 42 Group of A. a. pilshryi new subspecies 52 Group of A. a. turgida Newcomb 57 Group of A. a. polymorpha Gulick 91 Group of A. a. leiicorraphe Gulick loi Group of A. a. invini Pilsbry and Cooke 115 Group of A. a. coniformis Gulick 126 Group of A. a. lilacea Gulick 133 Group of A. a. apicata Newcomb , 146 Group of A. a. aloha Pilsbry and Cooke 160 Group of A. a. apexjulva Dixon 176 Conclusions 188 Summary 206 References 208 Explanation of plates 208 Plates 1-12 224 Index to sections, genera, species, and subspecies 225 Index to place names 229 INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF WORK In a previous paper (Welch, 1938) the species Achatinella mustelina is studied. -

Appendix ES-8B Achatinella Dietary Preferences

Appendix ES-8B Achatinella Dietary Preferences Escaping the captive diet: enhancing captive breeding of endangered species by determining dietary preferences Richard O’Rorke1, Brenden S Holland2, Gerry M Cobian1, Kapono Gaughen1, Anthony S Amend1 1 Department of Botany, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 2 Center for Conservation Research & Training, Pacific Biosciences Research Center, University of Hawaii, Honolulu HI 98822 USA Abstract Endangered species can be safeguarded against extinction by raising subpopulations in ex situ facilities that mimic their wild habitats. This is difficult when the endangered animal’s diet is cryptic. We present a combined molecular and behavioral approach to assess the ex situ diet of Achatinella, a critically endangered genus of tree snail, to determine how diet of captive snails differs from wild snails. Ex situ snails are currently fed biofilms growing on the surface of leaves, as well as a cultured fungus isolated from this same habitat. Amplicon sequencing of DNA extracted from feces of cultured snails confirms that this cultured fungus is abundant in the wild, but that it dominates the diet of the ex situ snail diet (comprising ~38% of sequences). The diet of captive snails is significantly less diverse compared to wild snails. To test the hypothesis that snails have diet preferences, we conducted feeding trials. These used a surrogate snail species, Auriculella diaphana, which is a confamilial Oahu endemic, though non-federally listed. Contrary to our expectations we found that snails do have feeding preferences. Furthermore, our feeding preference trials show that over all other feeding options snails most preferred the “no-microbe” control, which consisted only of potato dextrose agar (PDA). -

COA Supplement No. 1 a Review of National and International Regulations Concerned with Collection, Importation

Page 2 COA Supplement No. 1 In 1972, a group of shell collectors saw the need for a national organization devoted to the interests of shell collec- tors; to the beauty of shells, to their scientific aspects, and to the collecting and preservation of mollusks. This was the start of COA. Our member- AMERICAN CONCHOLOGIST, the official publication of the Conchol- ship includes novices, advanced collectors, scientists, and shell dealers ogists of America, Inc., and issued as part of membership dues, is published from around the world. In 1995, COA adopted a conservation resolution: quarterly in March, June, September, and December, printed by JOHNSON Whereas there are an estimated 100,000 species of living mollusks, many PRESS OF AMERICA, INC. (JPA), 800 N. Court St., P.O. Box 592, Pontiac, IL 61764. All correspondence should go to the Editor. ISSN 1072-2440. of great economic, ecological, and cultural importance to humans and Articles in AMERICAN CONCHOLOGIST may be reproduced with whereas habitat destruction and commercial fisheries have had serious ef- proper credit. We solicit comments, letters, and articles of interest to shell fects on mollusk populations worldwide, and whereas modern conchology collectors, subject to editing. Opinions expressed in “signed” articles are continues the tradition of amateur naturalists exploring and documenting those of the authors, and are not necessarily the opinions of Conchologists the natural world, be it resolved that the Conchologists of America endors- of America. All correspondence pertaining to articles published herein es responsible scientific collecting as a means of monitoring the status of or generated by reproduction of said articles should be directed to the Edi- mollusk species and populations and promoting informed decision making tor. -

Demographic and Genetic Factors in the Recovery Or Demise of Ex Situ Populations Following a Severe Bottleneck in Fifteen Species of Hawaiian Tree Snails

Demographic and genetic factors in the recovery or demise of ex situ populations following a severe bottleneck in fifteen species of Hawaiian tree snails Melissa R. Price1,2 , David Sischo3, Mark-Anthony Pascua4 and Michael G. Hadfield1 1 Kewalo Marine Laboratory, Pacific Biosciences Research Center, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa,¯ Honolulu, HI, USA 2 Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa,¯ Honolulu, HI, USA 3 Division of Forestry and Wildlife, Department of Land and Natural Resources, Honolulu, HI, USA 4 Biology Department, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa,¯ Honolulu, HI, USA ABSTRACT Wild populations of endangered Hawaiian tree snails have declined precipitously over the last century due to introduced predators and other human impacts. Life history traits, such as very low fecundity (<5 oVspring per year across taxa) and maturity at approximately four years of age have made recovery diYcult. Conservation eVorts such as in situ predator-free enclosures may increase survival to maturity by protecting oVspring from predation, but no long-term data existed prior to this study demonstrating the demographic and genetic parameters necessary to maintain populations within those enclosures. We evaluated over 20 years of evidence for the dynamics of survival and extinction in captive ex situ populations of Hawaiian tree snails established from wild-collected individuals. From 1991 to 2006, small numbers of snails (<15) from fifteen species were collected from the wild to initiate captive-reared populations as a hedge against extinction. This small number of founders resulted in a severe bottleneck in each of the captive-reared Submitted 6 July 2015 Accepted 26 October 2015 populations.