Afghanistan Transport Sector Master Plan Update (2017–2036)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UN Adopts Resolution on Afghanistan, Calls for End to Violence

Quote of the Day Experience www.outlookafghanistan.net Do you know” the difference between education” and facebook.com/The.Daily.Outlook.Afghanistan experience? Education is when you read the fine print; Email: [email protected] experience is what you get when you don’t. Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Add: In front of Habibia High School, Pete Seeger District 3, Kabul, Afghanistan Volume No. 4496 Saturday December 12, 2020 Qaws 22, 1399 www.outlookafghanistan.net Price: 20/-Afs Known Writer, Ghani Stresses Rapid Novelist UN Adopts Resolution on NFP Implementation Rahnaward Afghanistan, Calls for NFP on July 19 and at the time he had said that food items worth Zaryab $244 million would be distributed End to Violence to vulnerable families. Passes Away However, the Wolesi Jirga reject- ed the program on July 21 while the government stressed on its implementation. A statement from the Presiden- tial Palace received by Pajhwok Afghan News said that a meeting chaired by President Ghani dis- cussed the launch of the program KABUL - President Ashraf Ghani in the palace on Wednesday even- has said implementation of the ing. KABUL - Well-known writer, National Food Package (NFP) The meeting, also attended by novelist, journalist and liter- should be accelerated on the ac- first vice-president Amrullah ary scholar Rahnaward Zaryab count of the second wave of coro- Saleh, was briefed about the ad- passed away at the age of 77 years navirus in the country. vancement of the program by of- old at a hospital in Kabul early President Ghani inaugurated the ficials ...( More on P4)...(2) Friday morning. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

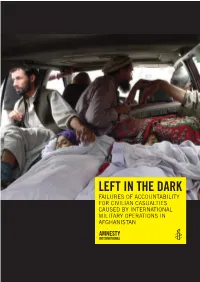

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Security Transitions∗

Security Transitions∗ Thiemo Fetzery Pedro CL Souzaz Oliver Vanden Eyndex Austin L. Wright{ March 18, 2020 Abstract How do foreign powers disengage from a conflict? We study the recent large- scale security transition from international troops to local forces in the context of the ongoing civil conflict in Afghanistan. We construct a new dataset that com- bines information on this transition process with declassified conflict outcomes and previously unreleased quarterly survey data. Our empirical design leverages the staggered roll-out of the transition onset, together with a novel instrumental variables approach to estimate the impact of the two-phase security transition. We find that the initial security transfer to Afghan forces is marked by a significant, sharp and timely decline in insurgent violence. This effect reverses with the ac- tual physical withdrawal of foreign troops. We argue that this pattern is consistent with a signaling model, in which the insurgents reduce violence strategically to facilitate the foreign military withdrawal. Our findings clarify the destabilizing consequences of withdrawal in one of the costliest conflicts in modern history and yield potentially actionable insights for designing future security transitions. Keywords:Counterinsurgency,Civil Conflict,Public Goods Provision JEL Classification: D72, D74, L23 ∗We thank Ethan Bueno de Mesquita, Wioletta Dziuda, Anthony Fowler, Hannes Mueller, Christo- pher Price, Jacob Shapiro, and audiences at the Chicago Harris Political Economy, ESOC Annual Con- ference, University of Warwick, IAE Barcelona Workshop on Prediction for Prevention, HiCN confer- ence, CREST Political Economy Workshop, and Labex OSE Aussois Days. Manh Duc Nguyen provided excellent research assistance. Support from the Pearson Institute for the Study and Resolution of Con- flicts is gratefully acknowledged. -

AFGHANISTAN Logar Province

AFGHANISTAN Logar Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Logar Province Reference Map 69°0'0"E 69°30'0"E Jalrez Paghman Legend District Kabul District District Bagrami ^! Capital Maydanshahr District District !! Provincial Center ! District Center ! Chaharasyab Musayi Surobi !! Chaharasyab District Administrative Boundaries Maydanshahr District District Nerkh Musayi ! ! Khak-e-Jabbar International ! Province Kabul Hesarak Distirict Wa rd ak Province District Transportation Province Khak-e-Jabbar Hesarak District Nangarhar ! Primary Road Province Secondary Road o Airport Chak Nerkh District District p Airfield Mohammadagha ! Mohammadagha River/Stream District River/Lake p Azra ! Azra Logar District Province Khoshi Pul-e-Alam Alikhel ! Saydabad Khoshi ! District !! (Jaji) Date Printed: 30 March 2014 08:40 AM 34°0'0"N 34°0'0"N District Barakibarak ! Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI Pul-e-Alam Alikhel Schools - Ministry of Education District (Jaji) ! ° ! Fata Health Facilities - Ministry of Health Kurram Barakibarak Agency Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 Saydabad District District 0 20 Kms Dand Wa Patan Lija District Ahmad Disclaimers: Khel The designations employed and the presentation of material ! Chamkani on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion District Charkh whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Chamkani District Paktya ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation ! Charkh Province Lija Ahmad Khel of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Afghanistan Partial Threat Assessment: the Taliban and Isis

CAITLIN FORREST AND ROB DENABURG with harleen gambhir Feburary 23, 2016 AFGHANISTAN PARTIAL THREAT ASSESSMENT: THE TALIBAN AND ISIS Key Takeaway: Security in Afghanistan has been deteriorating since U.S. force levels dropped from a high of 100,000 in 2011 to the current force size of 9,800 they reached in June 2014. Lt. Gen. John W. “Mick” Nicholson, the incoming commander of Operation Resolute Support and U.S. Forces in Afghanistan, agreed with the remark that “the security situation in Afghanistan has been deteriorating rather than improving” in a Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) hearing on January 28. Outgoing Resolute Support Commander General John Campbell reiterated this concern on February 2, stating that the ability to train Afghan security forces will be “very limited” if U.S. forces are reduced to 5,500 by the end of January 2017 as planned. Taliban militants are capitalizing on the overextension of the Afghanistan National Security Forces (ANSF) and dearth of U.S. and NATO forces to increase attacks, particularly in Helmand Province. ISW last published its Afghanistan Threat Assessment on December 11, 2015. Since then, Taliban militants have regained much of their traditional stronghold of Helmand Province, taking control of Now Zad and Musa Qal’ah Districts after ANSF withdrew between February 20 and 22. Militants are also besieging ANSF in Sangin and Marjah Districts while attacking ANSF near Gereshk, the district center of Nahr-e Saraj. The Taliban is thereby gaining freedom of maneuver around Helmand’s provincial capital, Lashkar Gah, even though they do not control the city itself. -

Afghanistan - United States Department of State

Afghanistan - United States Department of State https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-trafficking-in-persons-report/afghani... The Government of Afghanistan does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking and is not making significant efforts to do so; therefore Afghanistan was downgraded to Tier 3. Despite the lack of significant efforts, the government took some steps to address trafficking, including continuing to identify trafficking victims, prosecuting and convicting some traffickers, including two perpetrators of bacha bazı for kidnapping, and conducting four trainings for provincial anti-trafficking officers. The government increased the number of Child Protection Units (CPUs) at Afghan National Police (ANP) recruitment centers, which prevented the recruitment of 357 child soldiers. The government also took several broad child protection efforts, including authorizing formation of a National Child Protection Committee to address bacha bazı and hiring additional social workers. In response to allegations of the sexual abuse and sex trafficking of 165 boys in Logar province, an attorney general’s office (AGO) investigation identified 20 perpetrators; by the end of this reporting period, the investigation had produced nine arrests and two convictions for related offenses. However, during the reporting period, there was a government policy or pattern of sexual slavery in government compounds (bacha bazı) and recruitment and use of child soldiers. Despite local officials’ widespread acknowledgement that many police, especially commanders at remote checkpoints, recruited boys for Bacha bazı, some high-level and provincial authorities, including at the Ministry of Interior (MOI), categorically denied the existence of bacha bazı among police and would not investigate reports. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Politics and Governance in Afghanistan: the Case of Nangarhar

Uzbekistan Tajikistan n Researching livelihoods and China Turkmenistan Tu Nangarhar Kabul Afghanistan Iran Pakistan Politics and Governance in Arabian Sea Afghanistan: the Case of Nangarhar Province Working Paper 16 Ashley Jackson June 2014 Funded by the EC About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people in conflict-affected situations (CAS) make a living, access basic services like health care, education and water, and perceive and engage with governance at local and national levels. Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and international efforts at peace- and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one-year inception phase: § State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations § State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations § Livelihood trajectories and economic activity in conflict-affected situations The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), Focus1000 -

Ands) Final Report

Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ministry of Economy Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS) FINAL REPORT June 2014 I General Directorate of Policy & Result Based Monitoring Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ministry of Economy Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS) FINAL REPORT June 2014 General Directorate of Policy & Result Based Monitoring II Foreword by the President III Foreword by the Minister of Economy IV TABLE OF CONTENTS Titles Pages Foreword by the President III Foreword by Minister of Economy IV Table of Contents V – VII Executive Summery 1 CHAPTER ONE 13 Macroeconomic Updates 13 . Real Sector 13 13 . Gross Domestic Products (GDP) . 13 Nominal GDP Growth Rate 14 . GDP per Capita . 15 GDP Composition 16 Fiscal Sector 16 . Government Revenue . 18 Expenditure 19 Monetary Sector 19 . Monetary Inflation . Currency Exchange Rate 19 . 20 Foreign Currency Auction 20 . Commercial Banking . 21 Debts 22 . Foreign Direct Investment . 22 Currency In Circulation 23 . Trade Balance CHAPTER TWO 24 24 Details of the Report Security Sector 24 . 25-31 Outcome 1 – Outcome 9 31 . Challenges V . Suggestions 31 Governance Sector 32 . 33-44 Outcome 1 – Outcome 18 Justice Sector 45 45-51 . Outcome 1 – Outcome 9 Infrastructural Development & Natural Resources Sector 52 Energy Sub-sector 53 . 54-57 Outcome 1 – Outcome 5 58 . Challenges . 58 Suggestions and Recommendations 59 Water Resources Sub-sector 59-62 . Outcome 1 – Outcome 3 . 64 Key findings across this sector 64 . Suggestions and Recommendations Transportation and Civil Aviation Sub-sector 65 . 65-72 Outcome 1 – Outcome 8 73 . Challenges . 73 Recommendations 75 Telecommunication and Information Technology Sub-sector 75-78 . -

The Rise and Stall of the Islamic State in Afghanistan

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Casey Garret Johnson This report details the structure, composition, and growth of the Islamic State’s so-called Khorasan province, particularly in the eastern Afghan province of Nangarhar, and outlines considerations for international policymakers. More than sixty interviews with residents of Nangarhar and provincial and The Rise and Stall of national Afghan security officials carried out by The Liaison Office, an Afghan research and peacebuilding organization, in Nangarhar and Kabul in the spring and summer of 2016 informed this report. the Islamic State in ABOUT THE AUTHOR Afghanistan Casey Garret Johnson is an independent researcher focusing on violent extremism and local politics in Afghanistan. Summary • The Islamic State’s Khorasan province (IS-K) is led by a core of former Tehrik-e-Taliban Paki- stan commanders from Orakzai and Khyber Agencies of Pakistan; the majority of mid-level commanders are former Taliban from Nangarhar, with the rank and file a mixture of local Afghans, Pakistanis, and foreign jihadists mostly from Central Asia. • IS-K receives funding from the Islamic State’s Central Command and is in contact with lead- ership in Iraq and Syria, but the setup and day-to-day operations of the Khorasan province have been less closely controlled than other Islamic State branches such as that in Libya. • IS-K emerged in two separate locations in Afghanistan in 2014—the far eastern reaches of Nangarhar province along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, and Kajaki district of southern Helmand province.