Research Paper Impact Factor: 4. 695 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal IJMSRR E- ISSN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Power Politics in Kolathunadu (1663-1697)

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723 Mailaparambil, J.B. Citation Mailaparambil, J. B. (2007, December 12). The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER SIX POWER POLITICS IN KOLATHUNADU (1663-1697) In the month of October 1690, three Dutch soldiers deserted from the Dutch fortress in Cannanore and were caught by the Nayars of the Kolathiri prince, Keppoe Unnithamburan, in Maday—a place some twenty kilometres to the north of Cannanore.1 Although they tried to hide their real identity by claiming first that they were English and later Portuguese, the Nayars who were sent by the Company to track them successfully exposed their pretensions. Realizing the graveness of the situation, the soldiers desperately pleaded with the Prince not to extradite them to the Company for fear of capital punishment. Moved by their pathetic imploring, the Prince took them under his protection and ordered the Company Nayars to turn back, stating that he would take them to Cannanore personally, which, in fact, did not happen. The Company servants complained about this incident to the Ali Raja. The latter assured them he would settle the issue by promising to advise and caution the inexperienced young prince regarding this issue. -

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

M. R Ry. K. R. Krishna Menon, Avargal, Retired Sub-Judge, Walluvanad Taluk

MARUMAKKATHAYAM MARRIAGE COMMISSION. ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES BY M. R RY. K. R. KRISHNA MENON, AVARGAL, RETIRED SUB-JUDGE, WALLUVANAD TALUK. 1. Amongst Nayars and other high caste people, a man of the higher divi sion can have Sambandham with a woman of a lower division. 2, 3, 4 and 5. According to the original institutes of Malabar, Nayars are divided into 18 sects, between whom, except in the last 2, intermarriage was per missible ; and this custom is still found to exist, to a certain extent, both in Travan core and Cochin, This rule has however been varied by custom in British Mala bar, in Avhich a woman of a higher sect is not now permitted to form Sambandham with a man of a lower one. This however will not justify her total excommuni cation from her caste in a religious point of view, but will subject her to some social disabilities, which can be removed by her abandoning the sambandham, and paying a certain fine to the Enangans, or caste-people. The disabilities are the non-invitation of her to feasts and other social gatherings. But she cannot be prevented from entering the pagoda, from bathing in the tank, or touch ing the well &c. A Sambandham originally bad, cannot be validated by a Prayaschitham. In fact, Prayaschitham implies the expiation of sin, which can be incurred only by the violation of a religious rule. Here the rule violated is purely a social one, and not a religious one, and consequently Prayaschitham is altogether out of the place. The restriction is purely the creature of class pride, and this has been carried to such an extent as to pre vent the Sambandham of a woman with a man of her own class, among certain aristocratic families. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

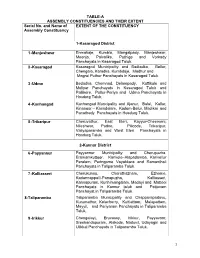

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep

Socioeconomic Monitoring for Coastal Managers of South Asia: Field Trials and Baseline Surveys Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep Project completion Report: NA10NOS4630055 Project Supervisor : Vineeta Hoon Site Coordinators: Idrees Babu and Noushad Mohammed Agatti team: Amina.K, Abida.FM, Bushra M.I, Busthanudheen P.K, Hajarabeebi MC, Hassan K, Kadeeshoma C.P, Koyamon K.G, Namsir Babu.MS, Noorul Ameen T.K, Mohammed Abdul Raheem D A, Shahnas beegam.k, Shahnas.K.P, Sikandar Hussain, Zakeer Husain, C.K, March 2012 This volume contains the results of the Socioeconomic Assessment and monitoring project supported by IUCN/ NOAA Prepared by: 1. The Centre for Action Research on Environment Science and Society, Chennai 600 094 2. Lakshadweep Marine Research and Conservation Centre, Kavaratti island, U.T of Lakshadweep. Citation: Vineeta Hoon and Idrees Babu, 2012, Socioeconomic Monitoring and Assessment for Coral Reef Management at Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep, CARESS/ LMRCC, India Cover Photo: A reef fisherman selling his catch Photo credit: Idrees Babu 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 7 Acknowledgements 8 Glossary of Native Terms 9 List of Acronyms 10 1. Introduction 11 1.1 Settlement History 11 1.2 Dependence on Marine Resources 13 1.3 Project Goals 15 1.4 Report Chapters 15 2. Methodology of Project Execution 17 2.1 SocMon Workshop 17 2.2 Data Collection 18 2.3 Data Validation 20 3. Site Description and Island Infrastructure 21 3.1 Site description 23 3.2. Community Infrastructure 25 4. Community Level Demographics 29 4.1 Socio cultural status 29 4.2 Land Ownership 29 4.3 Demographic characteristics 30 4.4 Household size 30 4.5. -

CLIVE FARAHAR RARE BOOKS 11 Middle Street Montacute Somerset TA15 6UZ U.K

MONTACUTE MISCELLANY CATALOGUE 94 ITEM 15 CLIVE FARAHAR RARE BOOKS 11 Middle Street Montacute Somerset TA15 6UZ U.K. +44(0)1935 593086 +44(0)7780 434713 [email protected] www. clivefarahar.com CONTENTS AFRICA 3,7,8,15,49. JAPAN 21,30. AMERICAN JUVENILE MANUSCRIPTS 8,10,11,18,20,49. BROADSHEETS 1. MEDCINE 20,38. THE AMERICAS MIDDLE EAST 67. 2,16,23,32,33,62,63,70,89. MILITARY 60. ARAB DICTIONARY POOLE 35. NELSON VICTORY COPPER 69. ASIA 51,52,61,64. PHOTOGRAPHY 29,31. AUSTRALASIA 36 POLARIS NEUCLEAR BAKER (SIR SAMUEL) 3 PROGRAMME 47 BURTON (CAPT. SIR R.F.) 7,8,9. RAEMAEKERS GREAT WAR 97 CALLIGRAPHY 10,11. SHIPWRECKS 54 – 58. CATHOLICISM 12. SLAVERY 50. CHINA 4,6,13,31,40-46, 71-87. TURKEY 66. FRANCE 17. WALEY (ARTHUR)) 71-87. GENERAL 5,10. WEST INDIES 88 GREENLAND 68. WILDE (OSCAR) 89. INDIA 19,22,24 – 29,37, WILLIAM IV CORONATION 90. 48,65,91,97. WORLD WARS I & II 92 - 97. The prices are in pounds sterling. Postage is added at cost. Any item may be returned within a week of receipt for whatever reason. VAT is charged where relevant. My registration number is 941496700. For Bank Transfers National Westminster C.R. Farahar Account no. 50868608 Sort code 60 02 05 1. AMERICAN JUVENILE. A Collection of 43 Hand Coloured Catch Penny Broad Sheets each with between 12 and 20 woodcut illustrations, numbered 7,8,18,19,21 - 50,52-60.12 x 16 ins. 28 x 40.5 cms. some marginal staining affecting a few, Printed expressly for the Humoristic Publishing Co. -

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present)

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present) STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 Complementary Course of BA English/Economics/Politics/Sociology (CBCSS - 2019 ADMISSION) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Calicut University P.O, Malappuram, Kerala, India 673 635. 19302 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 : MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT) COMPLEMENTARY COURSE FOR BA ENGLISH/ECONOMICS/POLITICS/SOCIOLOGY Prepared by : Module I & II : Haripriya.M Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Scrutinised by : Sunil kumar.G Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Module III&IV : Dr. Ancy .M.A Assistant professor of History School of Distance Education University of Calicut Scrutinised by : Asharaf koyilothan kandiyil Chairman, Board of Studies, History (UG) Govt. College, Mokeri. Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 2 School of Distance Education CONTENTS Module I 4 Module II 35 Module III 45 Module IV 49 Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 3 School of Distance Education MODULE I INDIA AS APOLITICAL ENTITY Battle Of Plassey: Consolodation Of Power By The British. The British conquest of India commenced with the conquest of Bengal which was consummated after fighting two battles against the Nawabs of Bengal, viz the battle of Plassey and the battle of Buxar. At that time, the kingdom of Bengal included the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Wars and intrigues made the British masters over Bengal. The first conflict of English with Nawab of Bengal resulted in the battle of Plassey. -

The Chirakkal Dynasty: Readings Through History

THE CHIRAKKAL DYNASTY: READINGS THROUGH HISTORY Kolathunadu is regarded as one of the old political dynasties in India and was ruled by the Kolathiris. The Mushaka vamsam and the kings were regarded as the ancestors of the Kolathiris. It was mentioned in the Mooshika Vamsa (1980) that the boundary of Mooshaka kingdom was from the North of Mangalapuram – Puthupattanam to the Southern boundary of Korappuzha in Kerala. In the long Sanskrit historical poem Mooshaka Vamsam, the dynastic name of the chieftains of north Malabar (Puzhinad) used is Mooshaka (Aiyappan, 1982). In the beginning of the fifth Century A.D., the kingdom of Ezhimala had risen to political prominence in north Kerala under Nannan… With the death of Nannan ended the most glorious period in the history of the Ezhimala Kingdom… a separate line of rulers known as the Mooshaka kings held sway over this area 36 (Kolathunad) with their capital near Mount Eli. It is not clear whether this line of rulers who are celebrated in the Mooshaka vamsa were subordinate to the Chera rulers of Mahodayapuram or whether they ruled as an independent line of kings on their own right (in Menon, 1972). The narration of the Mooshaka Kingdom up to the 12th Century A.D. is mentioned in the Mooshaka vamsa. This is a kavya (poem) composed by Atula, who was the court poet of the King Srikantha of Mooshaka vamsa. By the 14th Century the old Mooshaka kingdom had come to be known as Kolathunad and a new line of rulers known as the Kolathiris (the ‘Colastri’ of European writers) had come into prominence in north Kerala. -

Kannur School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 13001 Govt H S Pulingome G 13002 St. Marys H S Cherupuzha a 13003 St

Kannur School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 13001 Govt H S Pulingome G 13002 St. Marys H S Cherupuzha A 13003 St. Josephs English High School P 13004 Govt V H S S for Girls Kannur G 13005 Govt V H S S Kannur G 13006 ST TERESAS AIHSS KANNUR A 13007 ST MICHAELS AIHSS KANNUR A 13008 TOWN GHSS KANNUR G 13009 Govt. City High School, Kannur G 13010 DIS GIRLS HSS KANNUR CITY A 13011 Deenul Islam Sabha E M H S P 13012 GHSS PALLIKUNNU G 13013 CHOVVA HSS, CHOVVA A 13014 CHM HSS ELAYAVOOR A 13015 Govt. H S S Muzhappilangad G 13016 GHSS THOTTADA G 13017 Azhikode High School, Azhikode A 13018 Govt. High School Azhikode G 13019 Govt. Regional Fisheries Technical H S G 13020 CHMS GOVT. H S S VALAPATTANAM G 13021 Rajas High School Chirakkal A 13022 Govt. High School Puzhathi G 13023 Seethi Sahib H S S Taliparamba A 13024 Moothedath H S Taliparamba A 13025 Tagore Vidyanikethan Govt. H S S G 13026 GHSS KOYYAM G 13027 GHSS CHUZHALI G 13028 Govt. Boys H S Cherukunnu G 13029 Govt. Girls V H S S Cherukunnu G 13030 C H M K S G H S S Mattool G 13032 Najath Girls H S Mattool North P.O P 13033 Govt. Boys High School Madayi G 13034 Govt. H S S Kottila G 13035 Govt. Higher Secondary School Cheruthazham G 13036 Govt. Girls High School Madayi G 13037 Jama-Ath H S Puthiyangadi A 13038 Cresent E M H S Mattambram P 13039 Govt.