49 / Spectacle and Subversion in Trenchard-Smith's the Man from Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Reading

RECOMMENDED READING The following books are highly recommended as supplements to this manual. They have been selected on the basis of content, and the ability to convey some of the color and drama of the Chinese martial arts heritage. THE ART OF WAR by Sun Tzu, translated by Thomas Cleary. A classical manual of Chinese military strategy, expounding principles that are often as applicable to individual martial artists as they are to armies. You may also enjoy Thomas Cleary's "Mastering The Art Of War," a companion volume featuring the works of Zhuge Liang, a brilliant strategist of the Three Kingdoms Period (see above). CHINA. 9th Edition. Lonely Planet Publications. Comprehensive guide. ISBN 1740596870 CHINA, A CULTURAL HISTORY by Arthur Cotterell. A highly readable history of China, in a single volume. THE CHINA STUDY by T. Colin Campbell,PhD. The most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted. ISBN 1-932100-38-5 CHINESE BOXING: MASTERS AND METHODS by Robert W. Smith. A collection of colorful anecdotes about Chinese martial artists in Taiwan. Kodansha International Ltd., Publisher. ISBN 0-87011-212-0 CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS TRAINING MANUALS (A Historical Survey) by Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo CHRONICLES OF TAO, THE SECRET LIFE OF A TAOIST MASTER by Deng Ming-Dao. Harper San Francisco, Publisher ISBN 0-06-250219-0 (Note: This is an abridged version of a three- volume set: THE WANDERING TAOIST (Book I), SEVEN BAMBOO TABLETS OF THE CLOUDY SATCHEL (Book II), and GATEWAY TO A VAST WORLD (Book III)) CLASSICAL PA KUA CHANG FIGHTING SYSTEMS AND WEAPONS by Jerry Alan Johnson and Joseph Crandall. -

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey there, thanks for tuning in. Welcome, this is whistlekick martial arts radio and today were going to talk all about the man that I believe is the most underrated martial arts actor of today, possibly of all time, Sammo Hung. If you're new to the show you may not know my voice I'm Jeremy Lesniak, I'm the founder of whistlekick we make apparel and sparring gear and training aids and we produce things like this show. I wanna thank you for stopping by, if you want to check out the show notes for this or any of the other episodes we've done, you can find those over at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. You find our products at whistlekick.com or on Amazon or maybe if you're one of the lucky ones, at your martial arts school because we do offer wholesale accounts. Thank you to everyone who has supported us through purchases and even if you aren’t wearing a whistlekick shirt or something like that right now, thank you for taking the time out of your day to listen to this episode. As I said, here on today's episode, were talking about one of the most respected martial arts actor still working today, a man who has been active in the film industry for almost 60 years. None other the Sammo Hung. Also known as Hung Kam Bow i'll admit my pronunciation is not always the best I'm doing what I can. Hung originates from Hong Kong where he is known not only as an actor but also as an action choreographer, producer, and director. -

OUR GUARANTEE You Must Be Satisfied with Any Item Purchased from This Catalog Or Return It Within 60 Days for a Full Refund

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut February 26, 2016 These items are in limited supply and at these prices may sell out fast. DVD 1836234 ANCIENT 7623992 GIRL, MAKE YOUR MONEY 6545157 BERNSTEIN’S PROPHETS/JESUS’ SILENT GROW! A Sister’s Guide to ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: An Owner’s YEARS. Encounters with the Protecting Your Future and Enriching Manual. By David Hurwitz. In this Unexplained takes viewers on a journey Your Life. By G. Bridgforth & G. listener’s guide, and in conjunction through the greatest religious mysteries Perry-Mason. Delivers sister-to-sister with the accompanying 17-track audio of the ages. This set includes two advice on how to master the stock CD, Hurwitz presents all of Leonard investigations: Could Ancient Prophets market, grow your income, and start Bernstein’s significant concert works See the Future? and Jesus’ Silent Years: investing in your biggest asset—you. in a detailed but approachable way. Where Was Jesus All Those Years? 88 Book Club Edition. 244 pages. 131 pages. Amadeus. Paperbound. minutes SOLDon two DVDs. TLN. OU $7.95T Broadway. Orig. Pub. at $19.95 $2.95 Pub. at $24.99SOLD OU $2.95T 2719711 THE ECSTASY OF DEFEAT: 756810X YOUR INCREDIBLE CAT: 6410421 THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF Sports Reporting at Its Finest by the Understanding the Secret Powers ANTARCTIC JOURNEYS. Ed. by Jon Editors of The Onion. From painfully of Your Pet. By David Greene. E. Lewis. Collects a heart-pounding obvious steroid revelations to superstars Interweaves scientific studies, history, assortment of 32 true, first-hand who announce trades in over-the-top TV mythology, and the claims of accounts of death-defying expeditions specials, the world of sports often seems cat-owners and concludes that cats in the earth’s southernmost wilderness. -

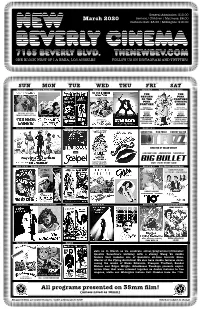

Newbev202003 FRONT

General Admission: $12.00 March 2020 Seniors / Children / Matinees: $8.00 NEW Cartoon Club: $8.00 / Midnights: $10.00 BEVERLY cinema 7165 BEVERLY BLVD. THENEWBEV.COM ONE BLOCK WEST OF LA BREA, LOS ANGELES FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM AND TWITTER! SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT March 1 & 2 Directed by Randal Kleiser March 3 March 4 & 5 March 6 & 7 Blake Edwards / Peter Sellers THE THE RETURN PINK OF THE PANTHER PINK STRIKES PANTHER AGAIN DIRECTED BY DIRECTED BY BLAKE EDWARDS BLAKE EDWARDS STARRING STARRING BROOKE SHIELDS PETER PETER CHRISTOPHER ATKINS SELLERS SELLERS CHRISTOPHER HERBERT LOM JOHN HUSTON’S PLUMMER COLIN BLAKELY CATHERINE SCHELL LEONARD ROSSITER HERBERT LOM LESLEY-ANNE DOWN March 8 & 9 Directed by Blake Edwards March 10 March 11 & 12 March 13 & 14 SIMON PEGG NICK FROST TIMOTHY DALTON DIRECTED BY EDGAR WRIGHT PLUS! BIGLAU CHING-WAN BULLET JORDAN CHAN THERESA LEE UGO TOGNAZZI MICHEL SERRAULT DIRECTED BY BENNY CHAN March 15 & 16 Barbara Stanwyck Double Feature March 17 March 18 & 19 March 20 & 21 Blake Edwards / Dudley Moore DUDLEY MOORE AMY IRVING ANN REINKING DUDLEY MOORE JULIE ANDREWS BO DEREK March 22 & 23 Directed by François Truffaut March 24 March 25 & 26 March 27 & 28 Quentin’s Birthday Double Feature JIMMY WANG YU Written, Directed by, and Starring Written & Directed by JIMMY WANG YU LO WEI March 29 & 30 March 31 Join us in March as we celebrate owner/programmer/fi lmmaker Quentin Tarantino’s birthday with a Jimmy Wang Yu double IB Tech Print feature that includes one of Quentin’s all-time favorite fi lms, IB Tech Print Master of the Flying Guillotine! We also have double features show- casing the works of Blake Edwards, François Truff aut, Randal Kleiser and Edgar Wright. -

Deathcheaters

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Goldsmith, Ben (2015) Deathcheaters. In Ryan, M, Lealand, G, & Goldsmith, B (Eds.) Directory of World Cinema: Australia and New Zealand 2. Intellect Ltd, United Kingdom, pp. 56-57. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/81217/ c Copyright 2015 Intellect Ltd. This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.intellectbooks.co.uk/ books/ view-Book,id=4951/ Pre-publication draft of chapter in Ben Goldsmith, Mark David Ryan and Geoff Lealand (eds) Directory of World Cinema: Australia -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Hong Kong Filmmakers Search: Hua Shan

HUA Shan 華山(b. 1942.2.9) Cinematographer, Director Also known as Hua Yihong, Hua was born in Shanghai and graduated from Shanghai Film Academy, specialising in cinematography. He came to Hong Kong in 1962 and joined Shaw Brothers (Hong Kong) Ltd the following year as an assistant to Japanese cinematographer Nishimoto Tadashi (He Lanshan). He was promoted to cinematographer in 1968. The 11 titles that he shot during this period, of which most of them were produced by Shaws, included Shen Chiang’s The Winged Tiger (1970), Jimmy Wang Yu’s directorial debut The Chinese Boxer (1970), Wu Ma’s Deaf and Mute Heroine (1971) and Ho Fan’s Love and Blood (1972). In 1973, Hua left Shaws and went to Taiwan to work as a director and made Spice of life (1974) and Underworld Beauty (1974). Hua returned to Shaws as a director in 1975 and began shooting Super Inframan (1975), with Chua Lam as the producer. It was also Hong Kong’s first sci-fi film with extensive special effects. The film did not score well at the Hong Kong box office, but was a hit at other places, thus establishing Hua’s position as director. Shaws then produced a five-part film series of major criminal cases in Hong Kong. Hua was the director for three of them, including The Valley of the Hanged in The Criminals (1976), Big Sister in Homicides—The Criminals, Part Two (1976) and No Escape for the Culprit in Arson—The Criminals, Part Three (1977). Meanwhile, he also shot Brotherhood (1976), which made Anthony Lau Wing a star. -

George Lazenby -- Trivia

George Lazenby -- Trivia Was the highest paid male model in Europe prior to playing James Bond. Except for TV commercials, he had no previous acting experience when he was cast as James Bond. Bond producer Albert R. Broccoli, remarked that Lazenby could have been the best Bond had he not quit after just one film. He was a martial arts instructor in the Australian army, and holds more than one black belt in the martial arts. He studied martial arts under Bruce Lee himself. He was set to co-star in the biggest budgeted action/martial arts film of all time in 1973, along with Bruce Lee. However, Lee died two weeks before the film was to begin shooting. (The film, originally titled "Shrine of Ultimate Bliss," was eventually made, but on a considerably smaller budget, and was given a limited theatrical release, excluding the U.S.) Broke a stuntman's nose during a Bond fight screen test, and it was this physical strength that finalized his selection as Bond. Was considered by producer Kevin McClory to play James Bond 007 in Never Say Never Again (1983) but was dropped from consideration when Sean Connery confirmed he wanted the role. He was offered a seven-movie deal by the Bond producers, but quit the role because he felt that the tuxedo-clad Bond would die out in the new hippie culture that had permeated society in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Was the #1 male fashion model in the world from 1964 to 1968. His agent, Maggie Smith, told him that he should apply for Bond, since in her opinion, his arrogance would surely win him the role. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth. -

Va.Orgjackie's MOVIES

Va.orgJACKIE'S MOVIES Jackie starred in his first movie at the age of eight and has been making movies ever since. Here's a list of Jackie's films: These are the films Jackie made as a child: ·Big and Little Wong Tin-Bar (1962) · The Lover Eternal (1963) · The Story of Qui Xiang Lin (1964) · Come Drink with Me (1966) · A Touch of Zen (1968) These are films where Jackie was a stuntman only: Fist of Fury (1971) Enter the Dragon (1973) The Himalayan (1975) Fantasy Mission Force (1982) Here is the complete list of all the rest of Jackie's movies: ·The Little Tiger of Canton (1971, also: Master with Cracked Fingers) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Juan Hsao Ten, Shih Tien, Han Kyo Tsi · DIRECTOR : Chin Hsin · STUNT COORDINATOR : Chan Yuen Long, Se Fu Tsai · PRODUCER : Li Long Koon · The Heroine (1971, also: Kung Fu Girl) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Cheng Pei-pei, James Tien, Jo Shishido · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · Not Scared to Die (1973, also: Eagle's Shadow Fist) · CAST : Wang Qing, Lin Xiu, Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung) · DIRECTOR : Zhu Wu · PRODUCER : Hoi Ling · WRITER : Su Lan · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · All in the Family (1975) · CAST : Linda Chu, Dean Shek, Samo Hung, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : Chan Mu · PRODUCER : Raymond Chow · WRITER : Ken Suma · Hand of Death (1976, also: Countdown in Kung Fu) · CAST : Dorian Tan, James Tien, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : John Woo · WRITER : John Woo · STUNT COORDINATOR : Samo Hung · New Fist of Fury (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Nora Miao, Lo Wei, Han Ying Chieh, Chen King, Chan Sing · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Han Ying Chieh · Shaolin Wooden Men (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Kam Kan, Simon Yuen, Lung Chung-erh · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · WRITER : Chen Chi-hwa · STUNT COORDINATOR : Li Ming-wen, Jackie Chan · Killer Meteors (1977, also: Jackie Chan vs. -

A Different Brilliance—The D & B Story

1. Yes, Madam (1985): Michelle Yeoh 2. Love Unto Wastes (1986): (left) Elaine Jin; (right) Tony Leung Chiu-wai 3. An Autumn’s Tale (1987): (left) Chow Yun-fat; (right) Cherie Chung 4. Where’s Officer Tuba? (1986): Sammo Hung 5. Hong Kong 1941 (1984): (from left) Alex Man, Cecilia Yip, Chow Yun-fat 6. It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World (1987): (front row from left) Loletta Lee, Elsie Chan, Pauline Kwan, Lydia Sum, Bill Tung; (back row) John Chiang 7. The Return of Pom Pom (1984): (left) John Sham; (right) Richard Ng 8. Heart to Hearts (1988): (from left) Dodo Cheng, George Lam, Vivian Chow Pic. 1-8 © 2010 Fortune Star Media Limited All Rights Reserved Contents 4 Foreword Kwok Ching-ling, Wong Ha-pak 〈Chapter I〉 Production • Cinema Circuits 10 D & B’s Development: From Production Company to Theatrical Distribution Po Fung Circuit 19 Retrospective on the Big Three: Dickson Poon and the Rise-and-Fall Story of the Wong Ha-pak D & B Cinema Circuit 29 An Unconventional Filmmaker—John Sham Eric Tsang Siu-wang 36 My Days at D & B Shu Kei In-Depth Portraits 46 John Sham Diversification Strategies of a Resolute Producer 54 Stephen Shin Targeting the Middle-Class Audience Demographic 61 Linda Kuk An Administrative Producer Who Embodies Both Strength and Gentleness 67 Norman Chan A Production Controller Who Changes the Game 73 Terence Chang Bringing Hong Kong Films to the International Stage 78 Otto Leong Cinema Circuit Management: Flexibility Is the Way to Go 〈Chapter II〉 Creative Minds 86 D & B: The Creative Trajectory of a Trailblazer Thomas Shin 92 From -

Golden Swallow, King Hu, and the Cold War = 《大醉俠》 : 金燕子、胡金銓與冷戰時代

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 8 Issue 1 Vol. 8.1 八卷一期 (2007) Article 10 1-1-2007 Come drink with me : If you dare : Golden Swallow, King Hu, and the Cold War = 《大醉俠》 : 金燕子、胡金銓與冷戰時代 Gina MARCHETTI University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Marchetti, G. (2007). Come drink with me: If you dare: Golden Swallow, King Hu, and the Cold War = 《大 醉俠》 : 金燕子、胡金銓與冷戰時代. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 8(1), 133-163. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Gina MARCHETTI 馬蘭清 Department of Comparative Literature, University of Hong Kong 香港大學比較文學系 COME DRINK WITH M E ------ If You Dare: Golden Swallow, King Hu, and the Cold War 《大醉俠》—— 金燕子、胡金銓與冷戰時代 133 A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.1 Mao Tse-tung, 1927 While the Chinese title f〇「Dazu/x/’a (大醉俠 Come D nM Me, 1 966) 「efe「s to its male lead, Drunken Cat (丫ueh Hua 岳華 )as the “ big drunk hero,” 1 1 "Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan" (March 1927), Selected Works o f Mao Tsu- tung, Vol.