Remaking the Iconic Lulu: Transformations of Character, Context, and Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Invoiced Expenditure Jan

Essex County Fire and Rescue Service January 2017 Purchase Invoice Data INVOICE DOCUMEN DEPARTMENT NOMINAL TYPE OF EXPENDITURE DESCRIPTION PERIOD YEARCODE VALUE ECFRS Ref SUPPLIER DATE T TYPE ICT 2510 IT Communications PAGER RENTAL 28/10/16-27/01/17 10 2017 4180.50 154808 05/10/2016 FPIN PAGEONE COMMUNICATIONS LTD Service Leadership Team 2902 Legal Expenses CANCELLED BY FPIN 157818 10 2017 28476.00 155469 04/11/2016 FPIN ESSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 52.00 155824 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 26.00 155824 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 598.00 155825 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 136.00 155825 18/11/2016 FPIN SI MEDICAL LTD Property Services 4003 Postage Direct Mailing & Carriage METER RESET 07.11.16 10 2017 25.50 156252 26/11/2016 FPIN PURCHASE POWER - PITNEY BOWES ICT 4005 IT Consumables HP - Low Voltage Power Supply 10 2017 229.00 156261 29/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC ICT 4005 IT Consumables call out charge to inspect/ser 10 2017 190.00 156261 29/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC ICT 4005 IT Consumables CREDIT FPIN 156261 10 2017 -95.00 156263 30/11/2016 FPIN UTILIZE PLC Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 112.00 156340 02/12/2016 FPIN PHYSIOTHERAPY ESSEX LTD Human Resources 0960 Occupational Health Occupational Health 10 2017 600.00 156340 02/12/2016 -

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Policing: Ethnic Identification Among African American Police in Washington, D.C

“Black-on-Black” Policing: Ethnic Identification Among African American Police in Washington, D.C. and Oakland, CA The study advances an emerging literature on African American intra- ethnic distinction in examining the phenomenon in the context of policing. Data from the study derives from in-depth interviews with African American police officers in Oakland, California and Washington, D.C. – two cities with substantial African American authority in the police department and in local government. I find that the African American officers interviewed in the study situate themselves within "ethnic mobility” narratives in which their work in the criminal justice system furthers African American group interests, in contrast with the perceptions of police work expressed by friends and family. I show that these narratives conceptualize low-income African American communities in both inclusive and exclusive terms, depending on how officers define ethnic mobility and ethnic welfare. The findings lend credibility to research on the malleability of ethnic solidarity, while also informing socio-legal scholarship investigating ethnic diversity as an avenue toward police reform. Keywords: police, African American, race, ethnicity, urban. The Negro, more than perhaps a member of any other group, is bound by his ethnic definition even when he becomes a policeman. Nicholas Alex, Black in Blue (1969) “If it were up to me, I’d build big walls and just flood the place. Biblical like. Flood the place and start a-fresh. I think that’s all you can do….I’d let the good people build an ark and float out. Old people, working people, line ‘em up two by two” [emphasis added]. -

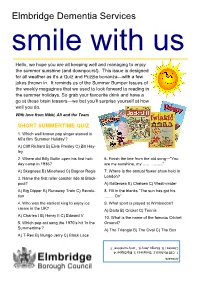

Elmbridge Dementia Services Smile with Us

Elmbridge Dementia Services smile with us Hello, we hope you are all keeping well and managing to enjoy the summer sunshine (and downpours!). This issue is designed for all weather as it’s a Quiz and Puzzle bonanza—with a few jokes thrown in. It reminds us of the Summer Bumper Issues of the weekly magazines that we used to look forward to reading in the summer holidays. So grab your favourite drink and have a go at these brain teasers—we bet you’ll surprise yourself at how well you do. With love from Nikki, Ali and the Team SHORT SUMMERTIME QUIZ 1. Which well known pop singer starred in 60’s film ‘Summer Holiday’? A) Cliff Richard B) Elvis Presley C) Bill Hay- ley 2. Where did Billy Butlin open his first holi- 6. Finish the line from the old song—”You day camp in 1936? are my sunshine, my ….. ……..” A) Skegness B) Minehead C) Bognor Regis 7. Where is the annual flower show held in 3. Name the first roller coaster ride at Black- London? pool? A) Battersea B) Chelsea C) Westminster A) Big Dipper B) Runaway Train C) Revolu- 8. Fill in the blanks “The sun has got his tion ……. On” 4. Who was the earliest king to enjoy ice 9. What sport is played at Wimbledon? cream in the UK? A) Darts B) Cricket C) Tennis A) Charles I B) Henry II C) Edward V 10. What is the name of the famous Cricket 5. Which pop act sang the 1970’s hit ‘In the Ground? Summertime’? A) The Triangle B) The Oval C) The Box A) T-Rex B) Mungo Jerry C) Black Lace ” 7. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Oscar Straus Beiträge Zur Annäherung an Einen Zu Unrecht Vergessenen

Fedora Wesseler, Stefan Schmidl (Hg.), Oscar Straus Beiträge zur Annäherung an einen zu Unrecht Vergessenen Amsterdam 2017 © 2017 die Autorinnen und Autoren Diese Publikation ist unter der DOI-Nummer 10.13140/RG.2.2.29695.00168 verzeichnet Inhalt Vorwort Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................5 Avant-propos Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................7 Wien-Berlin-Paris-Hollywood-Bad Ischl Urbane Kontexte 1900-1950 Susana Zapke (Wien) ................................................................................................................ 9 Von den Nibelungen bis zu Cleopatra Oscar Straus – ein deutscher Offenbach? Peter P. Pachl (Berlin) ............................................................................................................. 13 Oscar Straus, das „Überbrettl“ und Arnold Schönberg Margareta Saary (Wien) .......................................................................................................... 27 Burlesk, ideologiekritisch, destruktiv Die lustigen Nibelungen von Oscar Straus und Fritz Oliven (Rideamus) Erich Wolfgang Partsch† (Wien) ............................................................................................ 48 Oscar Straus – Walzerträume Fritz Schweiger (Salzburg) ..................................................................................................... 54 „Vm. bei Oscar Straus. Er spielte mir den tapferen Cassian vor; -

<H1>The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes</H1>

The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes "Lover and friend hast thou put far from me, and mine acquaintance into darkness." PSALM lxxxviii. 18 CHAPTER I Robert Bunting and Ellen his wife sat before their dully burning, carefully-banked-up fire. The room, especially when it be known that it was part of a house standing in a grimy, if not exactly sordid, London thoroughfare, was exceptionally clean and well-cared-for. A casual stranger, more particularly one of a Superior class to their own, on suddenly opening the door of that sitting-room; would have thought that Mr. page 1 / 387 and Mrs. Bunting presented a very pleasant cosy picture of comfortable married life. Bunting, who was leaning back in a deep leather arm-chair, was clean-shaven and dapper, still in appearance what he had been for many years of his life--a self-respecting man-servant. On his wife, now sitting up in an uncomfortable straight-backed chair, the marks of past servitude were less apparent; but they were there all the same--in her neat black stuff dress, and in her scrupulously clean, plain collar and cuffs. Mrs. Bunting, as a single woman, had been what is known as a useful maid. But peculiarly true of average English life is the time-worn English proverb as to appearances being deceitful. Mr. and Mrs. Bunting were sitting in a very nice room and in their time--how long ago it now seemed!--both husband and wife had been proud of their carefully chosen belongings. -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE COMPLETED SYMPHONIC COMPOSITIONS OF ALEXANDER ZEMLINSKY DISSERTATION Volume I Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert L. -

How the Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Fall 2019 Show Her It's a Man's World: How the Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda Leann Bishop [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the American Literature Commons, Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Military History Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Bishop, Leann, "Show Her It's a Man's World: How the Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda" (2019). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1001. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1001 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Show Her It’s a Man’s World: The Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda An essay submitted to the University of Akron Williams Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors By: Leann Bishop December 2019 Bishop 1 1. -

Hans Rosbaud and the Music of Arnold Schoenberg Joan Evans

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 01:22 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Hans Rosbaud and the Music of Arnold Schoenberg Joan Evans Volume 21, numéro 2, 2001 Résumé de l'article Cette étude documente les efforts de Hans Rosbaud (1895–1962) pour URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014484ar promouvoir la musique d’Arnold Schoenberg. L’essai est en grande partie basé DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014484ar sur vingt années de correspondance entre le chef d’orchestre et le compositeur, échange demeuré inédit. Les tentatives de Rosbaud portaient déjà fruit Aller au sommaire du numéro pendant qu’il était en fonction à la radio de Francfort au début des années 1930. À la suite de l’interruption forcée due aux années nazies (au cours desquelles il a travaillé en Allemagne et dans la France occupée), Rosbaud a Éditeur(s) acquis une réputation internationale en tant que chef d’orchestre par excellence dédié aux œuvres de Schoenberg. Ses activités en faveur de Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités Schoenberg dissimulaient le projet, que la littérature sur celui-ci n’avait pas canadiennes encore relevé, de ramener le compositeur vieillissant en Allemagne. ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Evans, J. (2001). Hans Rosbaud and the Music of Arnold Schoenberg. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 21(2), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014484ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Eamonn Bell All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Music studies’s turn to computation during the twentieth century has engendered particular habits of thought about music, habits that remain in operation long after the music scholar has stepped away from the computer. The computational attitude is a way of thinking about music that is learned at the computer but can be applied away from it. It may be manifest in actual computer use, or in invocations of computationalism, a theory of mind whose influence on twentieth-century music theory is palpable. It may also be manifest in more informal discussions about music, which make liberal use of computational metaphors. In Chapter 1, I describe this attitude, the stakes for considering the computer as one of its instruments, and the kinds of historical sources and methodologies we might draw on to chart its ascendance. The remainder of this dissertation considers distinct and varied cases from the mid-twentieth century in which computers or computationalist musical ideas were used to pursue new musical objects, to quantify and classify musical scores as data, and to instantiate a generally music-structuralist mode of analysis. I present an account of the decades-long effort to prepare an exhaustive and accurate catalog of the all-interval twelve-tone series (Chapter 2). This problem was first posed in the 1920s but was not solved until 1959, when the composer Hanns Jelinek collaborated with the computer engineer Heinz Zemanek to jointly develop and run a computer program.