Ethnology of Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 27, folder “State Visits - Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 27 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN ~ . .,1. THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN A Profile On the Occasion of The Visit by The Emperor and Empress to the United States September 30th to October 13th, 1975 by Edwin 0. Reischauer The Emperor and Empress of japan on a quiet stroll in the gardens of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Few events in the long history of international relations carry the significance of the first visit to the United States of the Em peror and Empress of Japan. Only once before has the reigning Emperor of Japan ventured forth from his beautiful island realm to travel abroad. On that occasion, his visit to a number of Euro pean countries resulted in an immediate strengthening of the bonds linking Japan and Europe. -

Old Age in Pre-Nara and Nara Periods*

Old Age in Pre-Nara and Nara Periods by Susanne Formanek (Vienna) Demographic meaning of old age and age classes In trying to establish the demographic meaning of old age in the Pre-Nara and Nara Periods we learn from the surviving evidence that it was rare for people to reach an advanced age. It is likely that only 5 % or even less of all fifteen-years- olds in the Jômon Period could expect to live until the age of 50 or more. On the basis of life tables it can be seen that life expectancy, while being very low in all age classes, stayed at either virtually the same level or declined only very slowly after the age of 40 or 50; therefore the chances of living even longer after having attained that age were comparatively good.1 Very much the same structure but with improved overall mortality rates was apparently maintained till the Nara Period, where the koseki show persons of over 60 to account for 3 to 5 % of the population, a still small but by no means insignificant number, since about 40% of the population was made up by children under the age of 15. Thus the number of the aged was of no little importance among the adult popu- lation. Furthermore, having reached the age of 40 or 50, one had very good chances to live for another 20 or 30 years.2 This essay is a slightly improved version of a paper read at the Vth International Conference on Japanese Studies of the European Association for Japanese Studies in Durham, Septem- ber 1988. -

Supernatural Elements in No Drama Setsuico

SUPERNATURAL ELEMENTS IN NO DRAMA \ SETSUICO ITO ProQuest Number: 10731611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731611 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Supernatural Elements in No Drama Abstract One of the most neglected areas of research in the field of NS drama is its use of supernatural elements, in particular the calling up of the spirit or ghost of a dead person which is found in a large number (more than half) of the No plays at present performed* In these 'spirit plays', the summoning of the spirit is typically done by a travelling priest (the waki)* He meets a local person (the mae-shite) who tells him the story for which the place is famous and then reappears in the second half of the.play.as the main person in the story( the nochi-shite ), now long since dead. This thesis sets out to show something of the circumstances from which this unique form of drama v/as developed. -

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What Is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura This ritual dance is performed to purify the kagura site, with the performer carrying a Since ancient times, people in Japan have believed torimono (prop) while remaining unmasked. Various props are carried while the dance is that gods inhabit everything in nature such as rocks and History of Izumo Kagura Shichiza performed without wearing any masks. The name shichiza is said to derive from the seven trees. Human beings embodied spirits that resonated The Shimane Prefecture is a region which boasts performance steps that comprise it, but these steps vary by region. and sympathized with nature, thus treasured its a flourishing, nationally renowned kagura scene, aesthetic beauty. with over 200 kagura groups currently active in the The word kagura is believed to refer to festive prefecture. Within Shimane Prefecture, the regions of rituals carried out at kamikura (the seats of gods), Izumo, Iwami, and Oki have their own unique style of and its meaning suggests a “place for calling out and kagura. calming of the gods.” The theory posits that the word Kagura of the Izumo region, known as Izumo kamikuragoto (activity for the seats of gods) was Kagura, is best characterized by three parts: shichiza, shortened to kankura, which subsequently became shikisanba, and shinno. kagura. Shihoken Salt—signifying cleanliness—is used In the first stage, four dancers hold bells and hei (staffs with Shiokiyome paper streamers), followed by swords in the second stage of Sada Shinno (a UNESCO Intangible Cultural (Salt Purification) to purify the site and the attendees. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

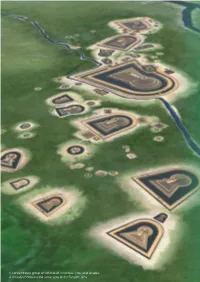

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples

Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History Vol. 179 November 2013 Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples YOSHIKAWA Shinji The abandoned temple of Okuyama (Okuyama Kumedera Temple) located at Okuyama in Asuka Village, Nara Prefecture is considered to be an old temple founded in the 620s or 630s, and identified with the Oharidadera Temple found in bibliographical sources of olden times. However, with regard to the circumstances of the foundation of the Oharidadera Temple, to date, no firmly established theory has been formed. In this paper by rereading historical materials relating to ancient times through to the medieval period, the following conclusions were obtained. 1. Oharidadera Temple in Asuka was the leading convent in the late 7th century, and even in the 8th century the temple had a close relation with the Imperial Family. It was confirmed that concurrently with the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo, the temple was moved to the northern outskirts of Heijyo-kyo, and the new temple was also called Oharidadera. 2. The Taikoji Temple in Nara, mentioned in historical materials covering the Heian period and later, in view of its geographical position, can be assumed to be the same as the Heijyo Oharidadera Temple. It would be reasonable to consider that Oharidadera Temple had the Buddhist name, Taikoji, since before the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo. 3. Private estates owned by Taikoji Temple in Yamato Province, mentioned in the Kanyo Ruijusho collection, were systematically arranged in locations convenient for overland transportation on the Nakatsu-Michi road and water transport on the Yamato River; against this background a strong admin- istrative and financial power can be inferred. -

Island Narratives in the Making of Japan: the Kojiki in Geocultural Context

Island Studies Journal, Ahead of print Island narratives in the making of Japan: The Kojiki in geocultural context Henry Johnson University of Otago [email protected] Abstract: Shintō, the national religion of Japan, is grounded in the mythological narratives that are found in the 8th-Century chronicle, Kojiki 古事記 (712). Within this early source book of Japanese history, myth, and national origins, there are many accounts of islands (terrestrial and imaginary), which provide a foundation for comprehending the geographical cosmology (i.e., sacred space) of Japan’s territorial boundaries and the nearby region in the 8th Century, as well as the ritualistic significance of some of the country’s islands to this day. Within a complex geocultural genealogy of gods that links geography to mythology and the Japanese imperial line, land and life were created along with a number of small and large islands. Drawing on theoretical work and case studies that explore the geopolitics of border islands, this article offers a critical study of this ancient work of Japanese history with specific reference to islands and their significance in mapping Japan. Arguing that a characteristic of islandness in Japan has an inherent connection with Shintō religious myth, the article shows how mythological islanding permeates geographic, social, and cultural terrains. The discussion maps the island narratives found in the Kojiki within a framework that identifies and discusses toponymy, geography, and meaning in this island nation’s mythology. Keywords: ancient Japan, border islands, geopolitics, Kojiki, mapping, mythology https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.164 • Received July 2020, accepted April 2021 © Island Studies Journal, 2021 Introduction This study interprets the significance of islands in Japanese mythological history. -

Origins of the Japanese Languages. a Multidisciplinary Approach”

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master’s Thesis “Origins of the Japanese languages. A multidisciplinary approach” verfasst von / submitted by Patrick Elmer, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 843 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Japanologie UG2002 degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Mag. Dr. Bernhard Seidl Mitbetreut von / Co-Supervisor: Dr. Bernhard Scheid Table of contents List of figures .......................................................................................................................... v List of tables ........................................................................................................................... v Note to the reader..................................................................................................................vi Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... vii 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Research question ................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Methodology ........................................................................................................ -

Speeltuin Der Kami

VAN RENTERGEM Stephanie Master Oosterse talen en culturen UGent: Academiejaar 2016-2017 Speeltuin der kami Volksgeloof in Yamato Verhandeling voor de lectuuropdracht in het kader van het vak “Masterproef: Japanologie” (Professor Christian Uhl) 0 Inhoudsopgave 1. Inleiding 3 2. De weg van de kami begint: het vroegste shintoïsme 6 2.1. Verklaring van termen 6 2.1.1. Shintoïsme 6 2.1.2. Kami 7 2.2. De oorsprong van het shintoïsme 13 2.3. Yamato: shintō wordt een systeem 16 3. Bloed, moeders en geesten: kenmerken van animisme 22 3.1. Inleiding 22 3.2. Spreken met geesten 24 3.2.1. Inleiding 24 3.2.2. Aard en benadering van de allervroegste "goden" (en kami) 24 3.2.3. Ouders van de Japanse eilanden 29 3.2.4. Rituele onzuiverheid in Yamato 31 3.3. Spelen met geesten 36 3.3.1. Inleiding 36 3.3.2.1. Bezetenheid in Yamato: menselijk subject 38 3.3.2.1.1. Bezetenheid van buitenuit 39 3.3.2.1.2. Bezetenheid van binnenuit 40 3.3.2.1.3. Bezetenheid van alle kanten 41 3.3.2.1.4. Bezetenheid als macht 43 3.3.2.1.5. Bezetenheid als de allerindividueelste expressie 47 3.3.2.2. Bezetenheid in Yamato: bovenmenselijk subject 47 3.3.3. Conclusie 51 3.4. "Moedermacht" 53 3.4.1. Inleiding 53 3.4.2. Matriarchaat in Yamato 55 3.5. Do ut des 62 3.5.1. Inleiding 62 3.5.2. Offers in Yamato: de vier variëteiten 63 3.5.2.1. -

Japanese Demon Lore Noriko T

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 1-1-2010 Japanese Demon Lore Noriko T. Reider [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Reider, N. T. (2010). Japanese demon lore: Oni, from ancient times to the present. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Japanese Demon Lore Oni from Ancient Times to the Present Japanese Demon Lore Oni from Ancient Times to the Present Noriko T. Reider U S U P L, U Copyright © 2010 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322 Cover: Artist Unknown, Japanese; Minister Kibi’s Adventures in China, Scroll 2 (detail); Japanese, Heian period, 12th century; Handscroll; ink, color, and gold on paper; 32.04 x 458.7 cm (12 5/8 x 180 9/16 in.); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; William Sturgis Bigelow Collection, by exchange, 32.131.2. ISBN: 978-0-87421-793-3 (cloth) IISBN: 978-0-87421-794-0 (e-book) Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free, recycled paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reider, Noriko T. Japanese demon lore : oni from ancient times to the present / Noriko T. Reider.