The Instrument of Voice an Interview with Robert Pinsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Bidart, Louise Glück, and Robert Pinsky

Chancellor's Distinguished Fellows Program 2004-2005 Selective Bibliography UC Irvine Libraries Frank Bidart, Louise Glück, Robert Pinsky March 11, 2005 Prepared by: John Novak Research Librarian for English & Comparative Literature, Classics and Critical Theory [email protected] and Lisa Payne Research Librarian Assistant [email protected] Note: For some Web links listed, access is restricted to resources licensed by the UCI Libraries. Table of Contents Frank Bidart .......................................................................................... p. 1 Louise Glück................................................................................................... p .4 Robert Pinsky ................................................................................................. p. 7 Frank Bidart Books & Poetry Collections of Bidart Bidart, Frank. Music Like Dirt. Louisville, Ky.: Sarabande Books, 2002. ________. Desire. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997. ________. In the Western Night: Collected Poems, 1965-90, ed. Joe Brainard. 1st ed. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1990. ________. "The War of Vaslav Nijinsky." (1984): 1 sound cassette (52 min.). 1 ________. The Sacrifice. New York: Random House, 1983. ________. The Book of the Body, ed. Joe Brainard. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977. ________. Golden State. New York: G. Braziller, 1973. Works edited by Bidart Lowell, Robert. Collected Poems, eds. Frank Bidart and David Gewanter. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. Essays by Bidart Bidart, Frank. "Pre-Existing Forms: We Fill Them and When We Fill Them We Change Them and Are Changed." Salmagundi 128 (Fall 2000): 109-122. ________, Wyatt Prunty, Richard Tillinghast, and James Kimbrell. "Panel: Lowell on the Page." Kenyon Review 22, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 234-248. ________. "'You Didn't Write, You Rewrote'." Kenyon Review 22, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 205-215. ________. "Like Hardy." Harvard Review 10 (Spring 1996): 115. -

Pw Ar07.Qxd:Layout 1

annual report 2006-2007 INTRODUCTION Last year, our signature Readings/Workshops program continued its nationwide expansion, made possible by our successful capital campaign in 2006, which enabled us to establish an endowment to bring the program to six new cities. In 2007, we began supporting writers participating in literary events in Washington, D.C. and in Houston. In Washington, D.C., we funded events taking place at venues, including Columbia Lighthouse for the Blind, Edmund Burke High School, and Busboys & Poets. We also partnered with Arte Publico Press, Nuestra Palabra, and Literal magazine to bring writers to audiences in Houston. In addition to the cities noted above, our Readings/Workshops program supports writers and organizations throughout New York State and California, and in Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, and Seattle. Last year, we provided $215,050 to 732 writers participating in 1,745 events. Poets & Writers Magazine celebrated its 20th anniversary last year and offered a number of helpful special sections, including a collection of articles on the increasingly popular MFA degree in creative writing. The magazine also took a look at writers conferences, including old favorites like Bread Loaf and Yaddo, as well as some newer destinations—the Macondo Workshop for Latino writers and Soul Mountain for African American writers. We also offered “The Indie Initiative,” our annual feature on small presses looking for new work, and “Big Six,” a snapshot of the country’s largest publishers of literary books. Our Information Services staff continued to provide trustworthy and personalized answers to hundreds of writers’ questions on topics ranging from vanity presses to literary agents. -

"We Must Answer for What We See": Exploring the Difficulty of Witness in the Poetry of Philip Levine, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Robert Pinsky

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2016 "We must answer for what we see": Exploring the Difficulty of Witness in the Poetry of Philip Levine, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Robert Pinsky Julia O. Callahan Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Callahan, Julia O., ""We must answer for what we see": Exploring the Difficulty of Witness in theoetr P y of Philip Levine, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Robert Pinsky". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2016. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/549 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! TRINITY!COLLEGE! ! ! ! Senior!Thesis! ! ! ! ! “We!must!answer!for!what!we!see”:!Exploring!the!Difficulty!of!Witness!in!the!Poetry! of!Philip!Levine,!Yusef!Komunyakaa,!and!Robert!Pinsky! ! ! submitted!by! ! ! Julia!Callahan!2016! ! ! ! In!Partial!Fulfillment!of!Requirements!for! ! the!Degree!of!BaChelor!of!Arts! ! ! 2016! ! ! Director:!Ciaran!Berry! ! Reader:!AliCe!Henton! ! Reader:!Clare!Rossini!! ! Table&of&Contents& ! Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………….……………………………...i! Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..........ii! Chapter!I:!“The!real!interrogator!is!a!voice!within”:!Vatic!Impulses!and!Civil!Obligations!in! the!Poetry!of!Philip!Levine!and!Yusef!Komunyakaa…………………………………………….....1! Chapter!II:!“In!the!haunted!ruin!of!my!consciousness”:!Robert!Pinsky’s!Representation!of! -

Exam List: Modernist Roots of Contemporary American Narrative Poetry Brian Brodeur

Exam List: Modernist Roots of Contemporary American Narrative Poetry Brian Brodeur Primary: 1. E.A. Robinson, Selected Poems (ed. Mezey) 2. Robert Frost, Robert Frost’s Poems (ed. Untermeyer) 3. Wallace Stevens, The Man with the Blue Guitar (1937) 4. T.S. Eliot, Collected Poems (1963), plus these essays: “Reflections on Vers Libre” (1917), “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1917) “Hamlet” (1919), “The Perfect Critic” (1920), “The Metaphysical Poets” (1921), “The Function of Criticism” (1923), “Ulysses, Order and Myth” (1923), and “Baudelaire” (1940) 5. Ezra Pound, Selected Cantos (1965) 6. W.C. Williams, Paterson (1963) 7. H.D., Trilogy (1946) 8. Robinson Jeffers, “Tamar” (1923), “Roan Stallion” (1925), “Prelude” (1926), “An Artist” (1928), “A Redeemer” (1928), “Cawdor” (1928), “The Loving Shepherdess” (1928), “Dear Judas” (1928), “Give Your Heart to the Hawks” (1933), “Hungerfield” (1948) 9. Hart Crane, The Bridge (1930) 10. Robert Lowell, Life Studies (1959) and The Dolphin (1973) 11. Theodore Roethke, The Far Field (1964) 12. Elizabeth Bishop, “The Man-Moth” (1946), “The Weed” (1946), “The Fish” (1946), “The Burglar of Babylon” (1965), “First Death in Nova Scotia” (1965), “In the Waiting Room” (1976), “The Moose” (1976), and “Santarem” (1978-9). 13. John Berryman, Homage to Mistress Bradstreet (1956) and The Dream Songs (1969) 14. James Merrill, The Changing Light at Sandover (1982) 15. Dana Gioia, David Mason, and Meg Schoerke, Twentieth-Century American Poetry (2003) Secondary: 1. Edgar Allan Poe, “The Poetic Principle” (1850) 2. Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature (1946) 3. Frank Kermode, “The Modern” (1967) 4. Hugh Kenner, The Pound Era (1971) 5. -

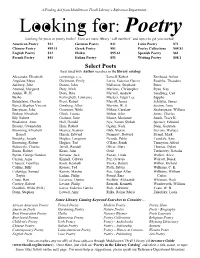

Poetry Looking for Poets Or Poetry Books? Here Are Some Library “Call Numbers” and Topics to Get You Started!

A Finding Aid from Middletown Thrall Library’s Reference Department… Looking for: Poetry Looking for poets or poetry books? Here are some library “call numbers” and topics to get you started! American Poetry 811 German Poetry 831 Latin Poetry 871 Chinese Poetry 895.11 Greek Poetry 881 Poetry Collections 808.81 English Poetry 812 Haiku 895.61 Spanish Poetry 861 French Poetry 841 Italian Poetry 851 Writing Poetry 808.1 Select Poets (best used with Author searches in the library catalog) Alexander, Elizabeth cummings, e. e. Lowell, Robert Rimbaud, Arthur Angelou, Maya Dickinson, Emily Lorca, Federico Garcia Roethke, Theodore Ashbery, John Donne, John Mallarme, Stephane Rumi Atwood, Margaret Doty, Mark Marlowe, Christopher Ryan, Kay Auden, W. H. Dove, Rita Marvell, Andrew Sandburg, Carl Basho Ferlinghetti, Lawrence Masters, Edgar Lee Sappho Baudelaire, Charles Frost, Robert Merrill, James Schuyler, James Benet, Stephen Vincent Ginsberg, Allen Merwin, W. S. Sexton, Anne Berryman, John Giovanni, Nikki Milosz, Czeslaw Shakespeare, William Bishop, Elizabeth Gluck, Louise Milton, John Simic, Charles Bly, Robert Graham, Jorie Moore, Marianne Smith, Tracy K. Bradstreet, Anne Hall, Donald Nye, Naomi Shihab Spenser, Edmund Brooks, Gwendolyn Hass, Robert Ogden, Nash Stein, Gertrude Browning, Elizabeth Heaney, Seamus Olds, Sharon Stevens, Wallace Barrett Hirsch, Edward Nemerov, Howard Strand, Mark Brodsky, Joseph Hughes, Langston Neruda, Pablo Teasdale, Sara Browning, Robert Hughes, Ted O'Hara, Frank Tennyson, Alfred Bukowski, Charles Jarrell, Randall Oliver, Mary Thomas, Dylan Burns, Robert Keats, John Ovid Trethewey, Natasha Byron, George Gordon Kerouac, Jack Pastan, Linda Walker, Alice Carson, Anne Kinnell, Galway Paz, Octavio Walcott, Derek Chaucer, Geoffrey Koch, Kenneth Pinsky, Robert Wilbur, Richard Collins, Billy Kooser, Ted Plath, Sylvia Williams, C. -

Poetry in America: the City from Whitman to Hip Hop

Poetry in America: The City from Whitman to Hip Hop SYLLABUS | Fall 2019 Course Team Instructor Elisa New, PhD, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, Harvard University Teaching Instructors Gillian Osborne, PhD, Instructor, Harvard Extension School ([email protected]) Sharon Howell, PhD, Instructor, Harvard Extension School (Contact via Canvas inbox) Course Managers Caitlin Ballotta Rajagopalan, Director of Educational Programs, Verse Video Education ([email protected]) Hogan Seidel, Course Designer, Video Production, & Course Manager, Poetry in America ([email protected]) Teaching Fellows Donald (Field) Brown ([email protected]) Jenna Ross ([email protected]) Alyssa Dawson (Contact via Canvas Inbox) Khriseten Bellows Contact via Canvas Inbox) Edyson Julio (Contact via Canvas Inbox) Brandon Lewis ([email protected]) Jesse Raber ([email protected]) Samantha St. Lawrence (Contact via Canvas Inbox) Sara Falls ([email protected]) MG Prezioso ([email protected]) Faith Henley Padgett ([email protected]) Course Overview In this course, we will consider American poets whose themes, forms, and voices have given expression to visions of the city since 1850. Beginning with Walt Whitman, the great poet of nineteenth-century New York, we will explore the diverse and ever-changing environment of the modern city—from Chicago to Washington, DC, from San Francisco to Detroit—through the eyes of such poets as Carl Sandburg, Emma Lazarus, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Langston Hughes, Marianne Moore, Frank O’Hara, Gwendolyn Brooks, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Hayden, and Robert Pinsky, as well as contemporary hip hop and spoken word artists. This course is especially designed for high school students and their teachers. -

LIBRARY of CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 Poetry Nation

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 poetry nation INSIDE Rosa Parks and the Struggle for Justice A Powerful Poem of Racial Violence PLUS Walt Whitman’s Words American Women Poets How to Read a Poem WWW.LOC.GOV In This Issue MARCH/APRIL 2015 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE FEATURES Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 4 No. 2: March/April 2015 Mission of the Library of Congress The Power of a Poem 8 Billie Holiday’s powerful ballad about racial violence, “Strange Fruit,” The mission of the Library is to support the was written by a poet whose works are preserved at the Library. Congress in fulfilling its constitutional duties and to further the progress of knowledge and creativity for the benefit of the American people. National Poets 10 For nearly 80 years the Library has called on prominent poets to help Library of Congress Magazine is issued promote poetry. bimonthly by the Office of Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and Beyond the Bus 16 The Rosa Parks Collection at the Library sheds new light on the research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in remarkable life of the renowned civil rights activist. 6 the United States. Research institutions and Walt Whitman educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. LCM is also available on the web at www.loc.gov/lcm. -

Writing America

A MILLENNIUM ARTS PROJECT REVISED EDITION NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS Contents Chairman’s Message 3 NEA Literature Fellows by State 4 Editor’s Note 5 The Writer’s Place by E.L. Doctorow 7 Biographies and Excerpts 8 2 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE WRITERS record the triumphs and tragedies of the human spirit and so perform an important role in our society. They allow us—in the words of the poet William Blake—“to see a world in a grain of sand,” elevating the ordinary to the extraordinary and finding signifi- cance in the seemingly insignificant. Creative writers in our own country deserve our support and encouragement. After all, America’s writers record America. They tell America’s story to its citizens and to the world. The American people have made an important investment in our nation’s writers through the National Endowment for the Arts’ Literature Fellowships. Since the program was established 35 years ago, $35 million has enhanced the creative careers of more than 2,200 writers. Since 1990, 34 of the 42 recipients of poetry and fiction awards through the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award have been recipients of Arts Endowment fellowships early in their careers. Beyond statistics, however, these writers have given a lasting legacy to American literature by their work. This revised edition of WRITINGAMERICA features the work of 50 Literature Fel- lowship winners—one from each state—who paint a vivid portrait of the United States in the last decades of the twentieth century. Collectively, they evoke the magnificent spectrum of people, places, and experiences that define America. -

“Newspoet” Tess Taylor

Agenda Item No. 4(B) EL CERRITO CITY COUNCIL PROCLAMATION In Recognition of El Cerrito Poet, Tess Taylor WHEREAS, El Cerrito Poet, Tess Taylor, was recently selected as National Public Radios's "All Things Considered," NewsPoet for the month of August and the El Cerrito City Council wishes to recognize and celebrate this and the many accomplishments of one its own residents; and WHEREAS, Ms. Taylor grew up in El Cerrito an4 attended Amherst College where she got her B.A, and New York University and Boston University where she obtained M.A.s in Journalism and Creative Writing; and WHEREAS, Ms. Taylor's work has appeared in a number of literary reviews such as the Atlantic Monthly, the Boston Review, The Times Literary Supplement, Memorious, and The New Yorker and she is the author of a chapbook of poems, The Misremembered World, which was published by the Poetry Society of America, and WHEREAS, in 2010-2011, Ms. Taylor was the Amy Clampitt Resident in Lenox, Massachusetts and in addition to being a poet she also works as a project editor and does freelance work as a journalist to publications such as the New York Times Magazine and Barnes and Noble Review; and WHEREAS, after 17 years away, Ms. Taylor returned to the City of El Cerrito and her first book, The Forage House, is due out in 2013 from Red Hen Press. NOW THEREFORE, the City Council of the City of El Cerrito does hereby recognize Ms. Tess Taylor for her many accomplishments in the literary field and celebrates her contributions in the areas of Arts and Humanities both locally and nationally. -

Longfellow House Bulletin, Vol. 2, No. 1, June 1998

on fellow ous L g ulletinH e Volume 2 No. 1 A Newsletter of the Friends of the Longfellow House June 1998 Longfellow House RehabilitationB Project: The Next Phase hase two, the planning stage, of the PLongfellow House Rehabilitation Pro- ject is now in process and is expected to continue through this summer and fall. After a year of extensive study of the House’s needs and resources, experts are drawing up plans for fre suppression, secu- rity, and electrical systems, an external fur- nace, handicap accessibility, climate control, and improved collection storage, as well as interior carriage house renovations. In addition to installing a state-of-the- art fre suppression system, upgrading the electrical system, and relocating the furnace from the basement to an external position, the renovations being planned will improve the House’s role as a research center. The rehabilitated research facilities will better preserve the collections and make them more accessible to researchers and the pub- The Longfellow House parlor as it looks today lic. Through the addition of climate con- provide a large meeting room for public lec- erations and to add to the House’s use as a trols and more storage shelves to the vault, tures and seminars with space for staV and scholarly and cultural center. the collection of over 600,000 photographs, research work. A small kitchen will be avail- Phase one of the Rehabilitation Project, letters, books, and art objects stored inside able for staV and House functions. a thorough assessment of the site’s needs will be archivally preserved, better orga- Phase two is part of the most extensive funded by the National Park Service, is now nized, and more easily retrievable. -

How-To-Read-A-Poem.Pdf

How to read a poem from Oak Meadow’s Write It Right: A Handbook for Student Writers Learning how to read and understand a poem take practice. It helps to approach poetry with an open mind and no prior expectations. Most readers make three false assumptions when addressing an unfamiliar poem. The first is assuming that they should understand what they encounter on the first reading, and if they don’t, that something is wrong with them or with the poem. The second is assuming that the poem is a kind of code, that each detail corresponds to one, and only one, thing, and unless they can crack this code, they’ve missed the point. The third is assuming that the poem can mean anything readers want it to mean. (“How to Read a Poem,” excerpted from Modern American Poetry) There is no one right way to approach a poem, but if you are new to poetry, these guidelines may be helpful. First, read the poem aloud, just experiencing the sound and rhythm of the words as a kind of music. Read the poem aloud several more times, speaking slowly. This helps you attend to each carefully chosen word. Use a natural tone of voice—no need to give a dramatic reading like an actor on stage. Let the words “speak” for themselves. Pause only when punctuation dictates, not at the end of each line break (which can interrupt the flow of the words). Read the poem again, this time paying attention to how the line breaks encourage you to phrase things or pause. -

Nature, Fidelity, and the Poetry of Robert Hass

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Nature, Fidelity, and the Poetry of Robert Hass A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Sarah Jane Barnett 2014 Abstract This thesis uses two methods of investigation—a critical essay on Robert Hass and a collection of poetry—to explore the relationship between contemporary poetry and the natural world. Central to the early collections of American poet Robert Hass is the question of whether language can depict the natural world. Hass uses techniques to try to accurately describe the natural world in some poems, while suggesting in others that language is limited in its ability to represent the natural world. Hass’s use and refusal of poetic technique, and the tension it creates, has not previously been explored in the critical literature. To address this critical gap, I use a third-wave ecocritical approach to examine Hass’s depiction of “nature” in his collections Field Guide, Praise, Human Wishes, and Sun Under Wood. The examination explores Hass’s use of scientifically accurate names and descriptions to realistically depict the natural world, which suggest that Hass sees the natural world as knowable, particular, and valuable; the way his poems depict humans as animals by drawing comparisons between human and nonhuman behaviour, but also suggests that humans are separated from other animals by language, rational thought, and self-awareness; and Hass’s use of three strategies—that of showing the limitations of language, qualifying language, and the theme of loss—to explore the role of the poem in our relationship to the natural world.