Download the Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 4 SECURITY for RESIDENTIAL PROPERTIES It’S One of the Most Basic Human Needs—Feeling Safe and Secure in Your Own Home

Special DOUBLE ISSUE JOURNALTHE CAMBRIDGE SECURITY Issue 4 SECURITY FOR RESIDENTIAL PROPERTIES It’s one of the most basic human needs—feeling safe and secure in your own home. Whether you own a house or townhouse in a gated community, a condominium in a luxury high rise, or rent a studio apartment in affordable housing, everyone craves the comfort of feeling “at home.” Ensuring that comfort is an important and rapidly growing part of our business. It may start with a free security survey that helps a property owner or manager identify their security needs. If it’s needed, we then develop a security plan that prioritizes those concerns and provides an integrated suite of solutions based on our client’s budget. Technology is almost always part of the solution, and while our company doesn’t make or install electronic security products, we know the industry well and often advise our clients on how they can best, and most cost-efficiently, deploy these valuable assets. What residential security always demands is people. We take enormous pride in the men and women we hire and the training we give them. We know that a Cambridge officer is likely to be the first friendly face a resident sees when she leaves in the morning, the first person to welcome her back when she returns in the evening, and the person who helps her rest easy when she’s at home. That’s a responsibility and a privilege we take very seriously. All the best, Ethan Lazar CEO, Cambridge Security For the latest news about Cambridge Security, please follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn Issue 4 SECURITY FOR RESIDENTIAL PROPERTIES Cambridge provides security for residential properties throughout the United States. -

Brian Seidman

ABSTRACT AND NOTHING BUT by Brian H. Seidman Steven Matthews’ family encouraged him to pursue acting, until rejection turns him away. Betrayed by those he trusted—their love keeping them from telling the truth—Matthews closes himself off from the world. Later, as a programmer, co-workers take advantage of Matthews, ruining his career. Disillusioned, unable to accept the help he needs, Matthews hires the company’s doorman as the most unlikely confidant. His request to the wizened James is as initially inexplicable as James’ acceptance, to take a stipend to tell Matthews the truth about himself. What follows is a picaresque San Francisco journey, from the Haight to the Golden Gate Bridge to the Tenderloin, from the minimum wage grind to the jetsetting lives of movie stars. Throughout, praise, criticism, lies, and the truth test their artificial friendship, examining truth in personal relationships and questioning the responsibilities we have to others as employees, as friends, and as human beings. AND NOTHING BUT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Brian H. Seidman Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2003 Advisor _____________________________________ Kay Sloan Reader ______________________________________ Constance Pierce Reader ______________________________________ Keith Banner © Brian H. Seidman 2003 Table of Contents PART I Chapter One How Much Does a Doorman Make? 2 Chapter Two Majordomo 12 Chapter Three The Thorn Field -

The Genesis of Theme in Salinger: a Study of the Early Stories

The genesis of theme in Salinger: a study of the early stories Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Taiz, Nard Nicholas, 1939- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 05:33:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/317934 THE GENESIS OF THEME IN SALINGER: A STUDY OF THE EARLY STORIES by Nard Nicholas Taiz A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 6 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission? provided that accurate acknowl edgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the inter ests of scholarship« In all other instances9 however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Monday 12/14/2020 Tuesday 12/15/2020 Wednesday 12/16/2020

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12/14/2020 12/15/2020 12/16/2020 12/17/2020 12/18/2020 12/19/2020 12/20/2020 4:00 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Dish Nation TMZ Live Weekend Marketplace 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 3:30 - 4:30 3:00 - 5:00 4:30 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Personal Injury Court Personal Injury Court (OTO) 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 5:00 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program PaidPatch Program v Miller Bell Paidv Young Program & Jones MyDestination.TV 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:30 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program The American Athlete 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 6:00 am Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Xploration Awesome Live Life and Win! Cutlers Cutlers Cutlers Cutlers Cutlers Planet 6:00 - 6:30 6:30 am Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Elizabeth6:00 - Stanton's 6:30 KarateTeen Kid, Kids Beating News the Schall6:30 v. -

Lesbian Romance Fiction 1928-2008 – an Exegetical Essay, And, Silver Lining: a Lesbian Romance Novel Diana Pamela Simmonds University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 And that night they were not parted: lesbian romance fiction 1928-2008 – an exegetical essay, and, Silver lining: a lesbian romance novel Diana Pamela Simmonds University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Simmonds, Diana Pamela, And that night they were not parted: lesbian romance fiction 1928-2008 – an exegetical essay, and, Silver lining: a lesbian romance novel, Master of Arts - Research thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4030 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] And That Night They Were Not Parted Lesbian Romance Fiction 1928-2008 – An Exegetical Essay And SILVER LINING: A Lesbian Romance Novel Diana Pamela Simmonds – 3336906 A thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirement for the Award of the Degree of Master of Arts (Research) of the University of Wollongong November 2013 CERTIFICATION I, Diana Pamela Simmonds, declare that this exegetical essay and manuscript, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Arts (Research), in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The documents have not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Diana Simmonds 11 November 2013 2 ABSTRACT This Master of Arts (Research) involves two components: a critical essay and a creative writing project. In the essay I discuss the romantic fiction genre and its constraints as they apply to lesbian romantic fiction. -

Renter's Guide Mns.Com

Renter’s Guide mns.com RENTER’S GUIDE THE DEAL ON RENTING IN MANHATTAN THE BASICS: In a city as large, dynamic, and diverse as New York, the rental process can be exciting, but also overwhelming. From brownstones to high-rises, New York City offers a dizzying array of options, and to help you navigate this sometimes daunting variety, it is important that you work with a broker who is knowledgeable, experienced and accessible. I am absolutely committed to finding the ideal apartment for you. orkingW together, we can get you acclimated with the current rental market, help you explore your housing options and prepare you for what is necessary to “qualify” for a New York City apartment. I am the only broker you’ll need, and all I ask is that you work with me exclusively. The following pages can be used as a guide to the apartment rental process in New York City. As always, I am here for you throughout your search and welcome any questions you may have. Please call today and experience the finest real estate service New York has to offer. I look forward to hearing from you. Warmest regards, Andrew Barrocas, CEO MNS Renter’s Guide page 3 Gramercy Park 212.475.9000 Williamsburg 718.222.1545 Williamsburg 718.222.0211 115 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010 165 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11211 40 North 6th Street, Brooklyn, NY 11249 mns.com All information furnished herein is from sources deemed reliable. No representation is made by MNS, nor is any to be implied as to the accuracy thereof. -

The Foreign Service Journal, November 1935

g/« AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ★ * JOURNAL * * VOL. XII NOVEMBER. 1935 No. 11 IT'S NO PLACE LIKE HOME /UCK While we’ve never seen the statistics, we’ll wager fast in your room, it quietly appears (with a flower and there’s no home in the country staffed with such reti¬ the morning paper on the tray). If you crave in-season nues of valets and butlers, chefs and secretaries, maids or out-of-season delicacies, you'll find them in any of and men servants, as our hotel. That’s why we say the our restaurants. Prepared with finesse and served with New Yorker is "no place like home" — purposely. We finesse. You may have your railroad or air-line or theatre know that everyone secretly longs for and enjoys the tickets ordered for you and brought to you. You may luxury of perfect hotel service. And you have your shirts and suits speeded back know it is yours at the New Yorker, with¬ from laundry or valet, with buttons sewed out luxurious cost. • It is unobtrusive ser¬ 25% reduction on and rips miraculously mended.You may vice, too, that never gets on your nerves. to diplomatic and have all this service by scarcely lifting a fin¬ Everyone—from the doorman to the man¬ consular service ger. • You will find the Hotel New Yorker NOTE: the special rate ager— is always friendly, always helpful— reduction applies only conveniently located, its staff pleasantly at¬ to rooms on which the tentive, and your bill surprisingly modest. but never effusive. If you want a lazy break¬ rate is $4 a day or more. -

Motoring Memories

MOTORING MEMORIES ONE MOTORIST’S EXPERIENCES i TABLE OF CONTENTS Motoring Memories 1 1954 Packard Clipper Deluxe Sedan 2 1956 Buick Century Riviera Coupe 16 Also Rans 23 1973 Buick Riviera 26 1979 Oldsmobile 98 Regency Sedan 28 1978 Cadillac DeVille Sedan 30 Other Cadillacs 32 1983 Ford Mustang GLX Convertible 33 1961 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II Sedan 34 Other People’s Cars 42 Grandfather White 42 The Pierce Arrow 43 Sylvia’s Hudson 44 ii My Father’s Riders 45 Clem’s Studebaker 46 My Parents’ 1955 Chevrolet 46 The Plymouth Valiant 48 More Packard Tales 48 Governor Browning’s Cadillac 49 The Cadillacs of Kroger 49 The Packards of Kroger 51 The Rolls-Royces of Kroger 53 The 1962 Buick Electra 54 Hodo’s Ford 55 The English Rental 57 Finale, For the Moment 58 iii MOTORING MEMORIES Motoring is an experience with an automobile, something that makes one=s interaction with an automobile memorable. It can be good or bad, a life changing experience, or just a memorable event or occasion. It can fix in your memory a series of sights, smells, and associations that linger there forever. Driving is just the function of taking a car from one place to another. Most of the time all of us merely drive, but there are times when we motor memorably. These are some of those stories. I cannot remember a time when cars were not important to me. After AMama@ and ADaddy,@ I am told that some of the first words I learned to say were ABuick@ and ADeSoto,@ cars then driven by two of the members of my family who drove me around a lot. -

The Foreign Service Journal, February 1935

9L AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ★ * JOURNAL * * IT'S NO PLACE LIKE HOME.J,u*h<*eU/ While we’ve never seen the statistics, we’ll wager fast in your room, it quietly appears (with a flower and there’s no home in the country staffed with such reti¬ the morning paper on the tray). If you crave in-season nues of valets and butlers, chefs and secretaries, maids or out-of-season delicacies, you'll find them in any of and men servants, as our hotel. That’s why we say the our restaurants. Prepared with finesse and served with New Yorker is "no place like home" — purposely. We finesse. You may have your railroad or air-line or theatre know that everyone secretly longs for and enjoys the tickets ordered for you and brought to you. You may luxury of perfect hotel service. And you have your shirts and suits speeded back know it is yours at the New Yorker, with¬ from laundry or valet, with buttons sewed out luxurious cost. • It is unobtrusive ser¬ 25^6 reduction on and rips miraculously mended. You may vice, too, that never gets on your nerves. to diplomatic and have all this service by scarcely lifting a fin¬ Everyone—from the doorman to the man¬ consular service ger. • You will find the Hotel New Yorker NOTE: the special rate ager—is always friendly, always helpful— reduction applies only conveniently located, its staff pleasantly at¬ to rooms on which the but never effusive. If you want a lazy break¬ rate is $4 a day or more. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Šárka Tripesová The Anatomy of Humour in the Situation Comedy Seinfeld Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Šárka Tripesová ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. for the invaluable guidance he provided me as a supervisor. Also, my special thanks go to my boyfriend and friends for their helpful discussions and to my family for their support. iii Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SEINFELD AS A SITUATION COMEDY 3 2.1 SEINFELD SERIES: THE REALITY AND THE SHOW 3 2.2 SITUATION COMEDY 6 2.3 THE PROCESS OF CREATING A SEINFELD EPISODE 8 2.4 METATHEATRICAL APPROACH 9 2.5 THE DEPICTION OF CHARACTERS 10 3 THE TECHNIQUES OF HUMOUR DELIVERY 12 3.1 VERBAL TECHNIQUES 12 3.1.1 DIALOGUES 12 3.1.2 MONOLOGUES 17 3.2 NON-VERBAL TECHNIQUES 20 3.2.1 PHYSICAL COMEDY AND PANTOMIMIC FEATURES 20 3.2.2 MONTAGE 24 3.3 COMBINED TECHNIQUES 27 3.3.1 GAG 27 4 THE METHODS CAUSING COMICAL EFFECT 30 4.1 SEINFELD LANGUAGE 30 4.2 METAPHORICAL EXPRESSION 32 4.3 THE TWIST OF PERSPECTIVE 35 4.4 CONTRAST 40 iv 4.5 EXAGGERATION AND CARICATURE 43 4.6 STAND-UP 47 4.7 RUNNING GAG 49 4.8 RIDICULE AND SELF-RIDICULE 50 5 CONCLUSION 59 6 SUMMARY 60 7 SHRNUTÍ 61 8 PRIMARY SOURCES 62 9 REFERENCES 70 v 1 Introduction Everyone as a member of society experiences everyday routine and recurring events. -

BARED Chapter 1 Excerpt

Chapter 1 “We should head to a bar and celebrate.” I wasn’t surprised by my roommate’s emphatic pronouncement. Cary Taylor found excuses to celebrate, no matter how small and inconsequential. I’d always considered it part of his charm. “I’m sure drinking the night before starting a new job is a bad idea.” “Come on, Eva.” Cary sat on our new living room floor amid a half dozen moving boxes and flashed his winning smile. We’d been unpacking for days, yet he still looked amazing. Leanly built, dark-haired, and green-eyed, Cary was a man who rarely looked anything less than absolutely gorgeous on any day of his life. I might have resented that if he hadn’t been the dearest person on earth to me. “I’m not talking about a bender,” he insisted. “Just a glass of wine or two. We can hit a happy hour and be in by eight.” “I don’t know if I’ll make it back in time.” I gestured at my yoga pants and fitted workout tank. “After I time the walk to work, I’m going to hit the gym.” “Walk fast, work out faster.” Cary’s perfectly executed arched brow made me laugh. I fully expected his million-dollar face to appear on billboards and fashion magazines all over the world one day. No matter his expression, he was a knockout. “How about tomorrow after work?” I offered as a substitute. “If I make it through the day, that’ll be worth celebrating.” “Deal. I’m breaking in the new kitchen for dinner.” “Uh . -

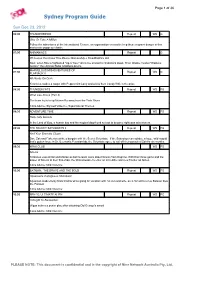

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 36 Sydney Program Guide Sun Dec 23, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Give Or Take A Million Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 ANIMANIACS Repeat G Of Course You Know This Means Warners/Up a Tree/Wakko's Giz Next, when Rita is frightened "Up a Tree," she's too scared to climb back down. Then Wakko creates "Wakko's Gizmo," the ultimate Rube Goldberg device. MARVELOUS MISADVENTURES OF 07:30 Repeat WS G FLAPJACK II All Hands On Deck K’nuckles makes a wager with Peppermint Larry and a kiss from Candy Wife is the prize. 08:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG What Lies Above (Part 2) The team try to keep Mumm-Ra away from the Tech Stone. Cons.Advice: Stylised Violence, Supernatural Themes 08:30 ADVENTURE TIME Repeat WS PG Holly Jolly Secrets In the Land of Ooo, a human boy and his magical dog friend set out to become righteous adventurers. 09:00 THE SECRET SATURDAYS II Repeat WS PG And Your Enemies Closer Doc, Zak and Fiskerton strike a bargain with the Secret Scientists. If the Saturdays can subdue a huge, wild cryptid that's gotten loose in Dr. Beeman's Peruvian lab, the Scientists agree to call off their pursuit of Zak for six months. 09:30 WINX CLUB WS PG Sirenix Tritannus uses Oritel and Marion as bait to learn more about Sirenix from Daphne. With their three gems and the power of Sirenix at their fingertips, the Winx prepare to enter an incredible and new frontier as fairies.