Gabrielle Chanel (1883-1971)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

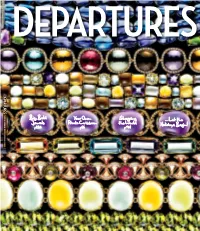

Let the Holidays Begin! Big,Bold Jewels Your Own Shopping the World

D D NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2013 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER Big, Bold Your Own Shopping ...Let the Jewels Private Caribbean the World Holidays Begin! p236 p66 p148 PERSONALBEST the business of scent A Whiff of Something Real As mass-produced perfumes become the new normal, the origin of a fragrance is more important than ever. TINA GAUDOIN reports from Grasse, the ancient home of perfume and the jasmine fields of Chanel No 5. oseph Mul drives his battered pickup into the dusty, rutted field of Jasminum gran- diflorum shrubs. It is 9 A.M. on a warm, slightly overcast September morning in Pégomas in southern France, about four miles from Grasse, the ancient home of Jperfume. In front of Mul’s truck, which is making easy work of the tough ter- rain, a small army of colorfully dressed pickers, most hailing from Eastern Europe, fans out, backs bent in pursuit of the elusive jasmine bloom that flowers over- night and must be harvested from the three-foot-high bushes before noon. By lunchtime, the petals will have been weighed by Mul, the numbers noted in the ledger (bonuses are paid by the kilo), and the pickers, who have been working since before dawn, will retire for a meal and a nap. Not so for Mul, who will oversee the beginnings of the lengthy distillation technique of turning the blooms into jasmine absolute, the essential oil and vital in- gredient in the world’s most famous and best- selling fragrance: Chanel No 5. All told, it’s a labor-intensive process. One picker takes roughly an hour to harvest one pound of jasmine; 772 pounds are required to make two pounds of concrete—the solution ARCHIVE ! WICKHAM/TRUNK ! MICHAEL !"! LTD ! NAST ! The post–World War II era marked the beginning of mass fragrance, when women wore perfume for more than just special occasions. -

The Zibby Garnett Travel Fellowship Report by Daisy Graham Textile

The Zibby Garnett Travel Fellowship Report by Daisy Graham Textile Conservation Placement at the Palais Galliera: Musée de la mode de Paris. 12th June 2017 – 3rd August 2017. 1 Contents Introduction…………………………………………..……………….……….……..5 Study Trip…………………………………………………………………..……..….5 Budget…………………………………………………………….…..………………6 Paris……………………………………………………………………………..……6 Palais Galliera: Musée de la mode de Paris……………………………………….….7 Arriving in Paris……………………………………………………………...……..11 Beginning the Placement…………………………………………………….……...12 Conserving Costume: the evening jacket…………………………………………...13 Conserving costume: the Eleonora dress……………………………………………14 Working in the Conservation Studio…………………………………………..……17 Opportunities and External Visits…………………………………………….…….19 Visit to Musée de la Vie romantique (Museum of Romantic Life)…………..……..19 Opening of “Costume Espagnols Entre ombre et lumière (Spanish Costume, between light and dark)” at La Maison Victor Hugo……………….………………………...20 Opening of “Christian Dior: Couturier des Rêves.……………….……………...….21 Trip to Angers…………………………...…………………………………………..24 Acknowledgments and thanks………………………...…………………………….26 2 List of Figures Figure 1: Map of France Figure 2: Eiffel Tower Figure3: Palais Galliera, main building Figure 4: Map of Paris. Figure 5: Recent exhibitions curated by the Palais Galliera. Figure 6: Working in the conservation studio Figure 7: Fondation Hellenqiue. Figure 8: The evening jacket on display Figure 9: The Eleonora dress on display Figure 10: Using melinex to shape the support Figure 11: Couching one of the supports in place Figure 12: Taking a pattern of the pocket Figure 13: The "rodeo trick” Figures 14 and 15: Eleonora dress left sleeve lining before and after conservation Figure 16 and 17: The front lining of the Eleonora dress before and after conservation Figure 18: Conserving the pleats Figure 19: Working on the jacket Figure 20: Musée de la Vie Romantique. -

Storied Perfume for Mystery Writers, Fragrance Is Often the Most Telltale Clue Left Behind at the Scene of a Crime

latimes.com LA STO RIES LA STYLE LA LIVING LA CULTURE LA BLO G S LA VIDEO S INSIDE L.A. BROWS E Past Issues Topics SEARCH S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 1 Storied Perfume For mystery writers, fragrance is often the most telltale clue left behind at the scene of a crime UNCOMMON SCENTS In the early stages of evolution, humans whose noses excelled at tracking prey—and could lead their tribe to water and alert it to big, musky predators—were rewarded with both survival and mates. DENISE HAMILTON Scientists say that while we can still distinguish up to 50,000 smells, the need for keen sniffers has dwindled in real life. And yet it flourishes in literature—especially crime fiction, where authors utilize fragrance as clues, psychological triggers and objects of obsession. Best known of the books is probably Patrick Süskind’s 1985 novel (and subsequent movie) Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, about an 18thcentury French idiot savant with olfactory perfect pitch who whips up a scent from the essence of a beautiful virgin that he has sniffed out in a secluded private garden, and the resulting odor is able to bewitch people into doing his bidding. Perfume is redolent with antique apothecaries, fragrant Grasse flower fields and enfleurage, the process of using odorless fats to capture the fragrant compounds that are exuded by plants. But crime novels featuring perfumes reach back to the 1920s and ’30s, the golden age of the classic French perfume houses. When sleuth Philo Vance sniffs the nozzle of an atomizer in a murdered lady’s bathroom in 1934’s Casino Murder Case, author S.S. -

Coco Chanel's Comeback Fashions Reflect

CRITICS SCOFFED BUT WOMEN BOUGHT: COCO CHANEL’S COMEBACK FASHIONS REFLECT THE DESIRES OF THE 1950S AMERICAN WOMAN By Christina George The date was February 5, 1954. The time—l2:00 P.M.1 The place—Paris, France. The event—world renowned fashion designer Gabriel “Coco” Cha- nel’s comeback fashion show. Fashion editors, designers, and journalists from England, America and France waited anxiously to document the event.2 With such high anticipation, tickets to her show were hard to come by. Some mem- bers of the audience even sat on the floor.3 Life magazine reported, “Tickets were ripped off reserved seats, and overwhelmingly important fashion maga- zine editors were sent to sit on the stairs.”4 The first to walk out on the runway was a brunette model wearing “a plain navy suit with a box jacket and white blouse with a little bow tie.”5 This first design, and those that followed, disap- 1 Axel Madsen, Chanel: A Woman of her Own(New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1990), 287. 2 Madsen, Chanel: A Woman of her Own, 287; Edmonde Charles-Roux, Chanel: Her Life, her world-and the women behind the legend she herself created, trans. Nancy Amphoux, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1975), 365. 3 “Chanel a La Page? ‘But No!’” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1954. 4 “What Chanel Storm is About: She Takes a Chance on a Comeback,” Life, March 1, 1954, 49. 5 “Chanel a La Page? ‘But No!’” 79 the forum pointed onlookers. The next day, newspapers called her fashions outdated. -

Representations of the Olfactory Concept in Advertising: a Case Study

Argumentum. Journal of the Seminar of Discursive Logic, Argumentation Theory and Rhetoric 16 (1): 80-93, 2018 Brînduşa-Mariana AMALANCEI “Vasile Alecsandri” University of Bacău (Romania) Representations of the Olfactory Concept in Advertising: A Case Study Abstract: The analysis of a perfume advertising image can be done from multiple perspectives, the endeavors to provide possible reading paths and interpretations being among the most diverse in the literature. Whether it is to meet the consumers’ psychological desires, to relate to fashion trends, or to create a rare scent, perfume advertising is a real challenge, which often needs to be answered just by juxtaposing an image and the product name. Our paper highlights the way in which the correlation between the visual and olfactory forms of perfumes is attempted, through product name, vial, characters, context and text (Julien 1997). Because in many advertisements the perfume is replacing the character, we chose as a case study an advertising image that we consider illustrating in this respect, that of the new olfactory creation of Chanel, Gabrielle, which appeared in September 2017. We have to mention that the launch of this product has been marked by the appearance of homage articles in glossy magazines, which contributes, through the information provided, to a better understanding of the message the advertisement transmits. Keywords: image, visual identity, olfactory concept, olfactory memory, brand name, perfume name, perfume bottle, advertising context 1. Fragrances ‒ Vectors of Communication Considered a privileged way of communication, perfumes are an identity mark (Vettraino-Soulard 1992, 106). We can often hear in advertisements about perfumes for strong women, perfumes that suit active women, perfumes for romantic women, etc. -

Trade Mark Decisions (O/223/17)

O-223-17 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION NO. 3139335 BY COCO’S LIBERTY LTD TO REGISTER THE TRADE MARK Coco’s Liberty IN CLASS 14 AND IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER NO. 406269 BY CHANEL LIMITED Background and pleadings 1) Coco’s Liberty Ltd (“the applicant”) applied to register under no 3139335 the mark “Coco’s Liberty” in the UK on 5 December 2015. It was accepted and published in the Trade Marks Journal on 18 December 2015 in respect of the following list of goods: Class 14: Jewellery, precious stones; Jewellery being articles of precious metals; Jewellery being articles of precious stones; Jewellery chain of precious metal for anklets; Jewellery chain of precious metal for necklaces; Jewellery coated with precious metal alloys; Jewellery coated with precious metals; Jewellery containing gold; Jewellery fashioned from bronze; Jewellery fashioned from non-precious metals; Jewellery fashioned of precious metals; Jewellery fashioned of semi-precious stones; Jewellery for personal adornment; Jewellery for personal wear; Jewellery in non-precious metals; Jewellery in semi-precious metals; Jewellery incorporating diamonds; Jewellery incorporating precious stones; Jewellery made from gold; Jewellery made from silver; Jewellery made of bronze; Jewellery made of non-precious metal; Jewellery made of precious metals; Jewellery made of precious stones; Jewellery made of semi-precious materials; Jewellery products; Jewellery rope chain for anklets; Jewellery rope chain for bracelets; Jewellery rope chain for necklaces; Jewellery plated with precious metals; Jewellery; Jewellery in precious metals; Jewellery of precious metals; Jewellery boxes. 2) Chanel Limited (“the opponent”) opposes the mark on the basis of section 5(2)(b), of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the Act”). -

Gabrielle Chanel, Fashion Manifesto by Lili Tisseyre

www.smartymagazine.com Gabrielle Chanel, Fashion Manifesto by Lili Tisseyre >> PARIS While Paris Fashion Week is in full swing, far from the usual catwalks, the Palais Galliera, dedicated to fashion, offers a sublime retrospective that celebrates the allure and vision of Chanel. The exhibition, which opened last October, could not welcome the expected public due to (re)confinement and the tribute did not have the expected echo. In those years when Paul Poiret dominated women's fashion, Gabrielle Chanel, from 1912 onwards, in Deauville, then in Biarritz and Paris, revolutionized the world of couture, printing a true fashion manifesto on the bodies of her contemporaries. SEE THE VIDEO The scenography is chronological. In the first room of the exhibition, the curator has chosen to evoke the beginnings of Coco Chanel by highlighting a few emblematic pieces, including the famous jersey sailor jacket created in 1916. Then we are invited to follow the evolution of Chanel's chic style: from the little black dresses and sporty models of the Roaring Twenties to the sophisticated dresses of the 1930s. Further on, an entire room is devoted to N°5. The flagship perfume and quintessence of the spirit of "Coco" Chanel, this fragance is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. Dialoguing with the ten chapters dedicated to it, ten photographic portraits of Gabrielle Chanel punctuate the scenography and affirm how much the couturier still embodies the brand. Then came the war and the closure of the fashion house; the only thing that remained in Paris was the sale of perfumes and accessories at 31 rue Cambon. -

Product Placement in Movie Industry

www.pwc.com/it 2012 Product Placement in Movie Industry Strategic Insights & Fashion Apparel Case Studies Agenda Page 1 Product Placement Overview in the Movie Industry 1 2 Product Placement in Movie Industry – Fashion Apparel 10 Case studies Section 1 Product Placement Overview in the Movie Industry PwC 1 Section 1 – Product Placement Overview in the Movie Industry PwC Strategy advises fashion clients in defining their marketing strategies There is a multiplicity of channels/means from which consumers can receive messages • Fashion shows Brand Awareness Seasonal • Media (TV, magazine, etc.) Exhibitions Instruments • • Catalogues • Sponsorships • … Customer Fidelisation • Showrooms • Corporate Magazines Institutional • Testimonials Instruments • … Product Sales increase Placement • Product Placements Emotional • Star Endorsements Lifestyle activities instruments • Global Reach • Shopping experience • … • Web site, social network, blog • Trunk Shows Stimulate a Relational • Word of mouth (co-marketing) Reaction instruments • Events • … PwC 2 Section 1 – Product Placement Overview in the Movie Industry How to reach a captive and involved audience? Product placement is a way of promoting a company or a product by using movies and other types of media to advertise the product or company. Product placements are often established by an agreement between a product manufacturer and the media company, in which the media company receives economic benefit. The Product Visual Placement - the (Placed product or brand) product, service, or logo can -

Teacher's Notes

For readers aged 4+ | 9781847807717 | Hardback | £9.99 Lots of the activities and discussion topics in these teacher’s notes are deliberately left open to encourage pupils to develop independent thinking around the book. This will help pupils build confidence in their ability to problem solve as individuals and also as part of a group. Little People, BIG DREAMS | teacher’s notes notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, 1 Little People, BIG DREAMS Teachers’ Notes © 2018 Frances Lincoln Children’s Books. All Rights Reserved. Written by Eva John. www.quartoknows.com The Front Cover What do you think Coco Chanel’s big dream might have been? Do you know anything about Coco Chanel? The Blurb Does the blurb suggest that your idea about Coco’s big dream was correct? Check your understanding of the following words and phrases: • orphanage • cabaret singer • seamstress • fashion designer • style icon If you are not quite sure, you could consult with friends, use a dictionary, or read the book to see if you can work it out for yourself. The Endpapers What effect does looking at the end papers have on you? Why do you think the illustrator decided on this design? This is the story of a young girl called Gabrielle. When she was little, Gabrielle lived in an orphanage. What is an orphanage? Who do you think ran the orphanage? What sort of childhood do you imagine Gabrielle had there? Little People, BIG DREAMS | teacher’s notes notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, 2 Little People, BIG DREAMS Teachers’ Notes © 2018 Frances Lincoln Children’s Books. -

Press Kit Shangri-La Hotel, Paris

PRESS KIT SHANGRI-LA HOTEL, PARIS CONTENTS Shangri-La Hotel, Paris – A Princely Retreat………………………………………………..…….2 Remembering Prince Roland Bonaparte’s Historic Palace………………………………………..4 Shangri-La’s Commitment To Preserving French Heritage……………………………………….9 Accommodations………………………………………………………………………………...12 Culinary Experiences…………………………………………………………………………….26 Health and Wellness……………………………………………………………………………..29 Celebrations and Events………………………………………………………………………….31 Corporate Social Responsibility………………………………………………………………….34 Awards and Talent..…………………………………………………………………….…….......35 Paris, France – A City Of Romance………………………………………………………………40 About Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts……………………………………………………………42 Shangri-La Hotel, Paris – A Princely Retreat Shangri-La Hotel, Paris cultivates a warm and authentic ambience, drawing the best from two cultures – the Asian art of hospitality and the French art of living. With 100 rooms and suites, two restaurants including the only Michelin-starred Chinese restaurant in France, one bar and four historic events and reception rooms, guests may look forward to a princely stay in a historic retreat. A Refined Setting in the Heart of Paris’ Most Chic and Discreet Neighbourhood Passing through the original iron gates, guests arrive in a small, protected courtyard under the restored glass porte cochere. Two Ming Dynasty inspired vases flank the entryway and set the tone from the outset for Asia-meets-Paris elegance. To the right, visitors take a step back in time to 1896 as they enter the historic billiard room with a fireplace, fumoir and waiting room. Bathed in natural light, the hotel lobby features high ceilings and refurbished marble. Its thoughtfully placed alcoves offer discreet nooks for guests to consult with Shangri-La personnel. Imperial insignias and ornate monograms of Prince Roland Bonaparte, subtly integrated into the Page 2 architecture, are complemented with Asian influence in the decor and ambience of the hotel and its restaurants, bar and salons. -

Second Quarter 2021

UPDATE ON NEGATIVE BLOOD AND URINE ANALYSES RESULTS IN 2021 IN THE EADCM PROGRAMME (updated 20.07.2021) DATE CATEGORY PLACE COUNTRY HORSE'S NAME NF PR April 01 - 04 CEI3*160/ MACRAES FLAT NZL GLENDAAR FIRE MAID NZL CEI2*120/CEI1*100/ GLENDAAR NISSAR NZL CEIYJ3*160/CEIYJ2*120/CEIYJ1*100 GLENDAAR WINDSONG NZL 02 - 04 CCI4*-S/ BRIGADOON AUS MISTY ISLE VALENTINO AUS CCI3*-S/CCI3*-L/ KENDLESTONE PARK HOLLYWOOD AUS CCI2*-S/CCI2*-L HAZID ROAD AUS ESB IRISH NYMPH AUS DVZ SOLITAIRE AUS ASTI HERA AUS 08 - 11 CCI4*-S/CCI4*-L/ PASO ROBLES USA DIEGO USA CCI3*-S/CCI3*-L/CCI2*-L DR. HART USA CAMPARI FFF USA LAGUNA SECA USA CINZANO USA CARAVAGGIO AUS HAPPINESS IS USA ADDYSON USA 09 - 11 CCI3*-S/ LIDGETON - DOLCOED RSA JEMADA JESTER RSA CCI2*-S/CCI1*-Intro WOW'S RJ RSA GIOVANNI RSA CALLAHO LISANDOR RSA WRAP UP RSA WRAP UP RSA PERIDOT RSA JUST JASPER AUS JUST JASPER AUS DAVENPORT RESOLUTION RSA 13 CEI1*100 GREOUX-LES-BAINS FRA DEMONJOI AL SHAQAB FRA BALKA DE SOMMANT FRA DANAT AL MONTASIR FRA VADJAL FRA 13 - 18 CSI4*/CSIJ-B/ MONTERREY MEX CLOCKWISE OF GREENHILL Z NZL CSICh-B/CSIAm-A ULRICH DU BOSCQ MEX TINO LA CHAPELLE MEX BOSTON ASK IRL STAN MEX HORTENSIA VAN DE LEEUWERK MEX PUERTAS LIZ MEX XUL HA MEX 14 - 18 CSIOY/CSIOJ/CSIYJ-A/ OPGLABBEEK BEL EASY KOLIBRA MO GER CSIOCh/CSIOP EYE OF THE TIGER BEL CONTIKI AH Z BEL PICOBELLE VAN DE BARTHOEVE BEL BINA NED VOODSTOCK DE L'ASTREE NED 14 - 18 CSI3*/CSI1*/CSIYH1* GORLA MINORE ITA CAIRON 10 FRA QUIN VON WORRENBERG Z FRA FORLAN VAN DE SPRENGENBERG NED LITTLE LUMPI E SUI COTTEE GBR PAXCRISTO VAN'T LAARHOF ITA ARAMIS DE LA BRESSE SUI 14 - 18 CSI2*/CSI1*/CSIYH1*/ AREZZO ITA KENTUCKY DV ITA CSIJ-B/CSICh-B/CSIP ARI DE KREISKER ITA CHACCO LOVER JR. -

“The Most Courageous Act Is Still to Think for Yourself. Aloud.” Coco Chanel

COCO CHANEL – MAVERICK TO ICON “The most courageous act is still to think for yourself. Aloud.” Coco Chanel Coco Chanel needs little introduction as a woman whose name has come to be synonymous with classic fashion and effortless style. During her lifetime she became the most famous female couturier in Europe and after her death was listed on the TIME’s 100 Most Influential People of the 20th Century. Few know the story behind the rise of the woman behind the interlocking CC emblem that represents the multibillion-dollar, privately owned luxury goods Chanel empire of today. What can we learn from this pioneering businesswoman that is relevant to this day? Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel was born 19th August 1883. Her mother was an unmarried laundry woman. Her father a nomadic street vendor. The couple had five children, including young Coco Chanel, all living in a crowded one-room lodging. When Chanel was just 12 years old, her mother died of tuberculosis. Her brothers were sent to work as farm labourers, and Chanel and her sisters were sent to the convent Aubazine which ran an orphanage in central France. It was in this frugal and austere period of her childhood that Chanel learned to sew, the skill that would make her an international fashion icon. At age 18 Chanel moved to a boarding house for Catholic girls in the town of Moulins. She sought work as a seamstress and in her free time sang in a cabaret bar frequented by cavalry officers. By the time she was 23, Coco had come to realise she would not have a serious stage career.