Talking Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

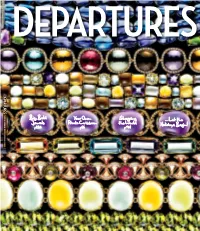

Let the Holidays Begin! Big,Bold Jewels Your Own Shopping the World

D D NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2013 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER Big, Bold Your Own Shopping ...Let the Jewels Private Caribbean the World Holidays Begin! p236 p66 p148 PERSONALBEST the business of scent A Whiff of Something Real As mass-produced perfumes become the new normal, the origin of a fragrance is more important than ever. TINA GAUDOIN reports from Grasse, the ancient home of perfume and the jasmine fields of Chanel No 5. oseph Mul drives his battered pickup into the dusty, rutted field of Jasminum gran- diflorum shrubs. It is 9 A.M. on a warm, slightly overcast September morning in Pégomas in southern France, about four miles from Grasse, the ancient home of Jperfume. In front of Mul’s truck, which is making easy work of the tough ter- rain, a small army of colorfully dressed pickers, most hailing from Eastern Europe, fans out, backs bent in pursuit of the elusive jasmine bloom that flowers over- night and must be harvested from the three-foot-high bushes before noon. By lunchtime, the petals will have been weighed by Mul, the numbers noted in the ledger (bonuses are paid by the kilo), and the pickers, who have been working since before dawn, will retire for a meal and a nap. Not so for Mul, who will oversee the beginnings of the lengthy distillation technique of turning the blooms into jasmine absolute, the essential oil and vital in- gredient in the world’s most famous and best- selling fragrance: Chanel No 5. All told, it’s a labor-intensive process. One picker takes roughly an hour to harvest one pound of jasmine; 772 pounds are required to make two pounds of concrete—the solution ARCHIVE ! WICKHAM/TRUNK ! MICHAEL !"! LTD ! NAST ! The post–World War II era marked the beginning of mass fragrance, when women wore perfume for more than just special occasions. -

Storied Perfume for Mystery Writers, Fragrance Is Often the Most Telltale Clue Left Behind at the Scene of a Crime

latimes.com LA STO RIES LA STYLE LA LIVING LA CULTURE LA BLO G S LA VIDEO S INSIDE L.A. BROWS E Past Issues Topics SEARCH S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 1 Storied Perfume For mystery writers, fragrance is often the most telltale clue left behind at the scene of a crime UNCOMMON SCENTS In the early stages of evolution, humans whose noses excelled at tracking prey—and could lead their tribe to water and alert it to big, musky predators—were rewarded with both survival and mates. DENISE HAMILTON Scientists say that while we can still distinguish up to 50,000 smells, the need for keen sniffers has dwindled in real life. And yet it flourishes in literature—especially crime fiction, where authors utilize fragrance as clues, psychological triggers and objects of obsession. Best known of the books is probably Patrick Süskind’s 1985 novel (and subsequent movie) Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, about an 18thcentury French idiot savant with olfactory perfect pitch who whips up a scent from the essence of a beautiful virgin that he has sniffed out in a secluded private garden, and the resulting odor is able to bewitch people into doing his bidding. Perfume is redolent with antique apothecaries, fragrant Grasse flower fields and enfleurage, the process of using odorless fats to capture the fragrant compounds that are exuded by plants. But crime novels featuring perfumes reach back to the 1920s and ’30s, the golden age of the classic French perfume houses. When sleuth Philo Vance sniffs the nozzle of an atomizer in a murdered lady’s bathroom in 1934’s Casino Murder Case, author S.S. -

Coco Chanel's Comeback Fashions Reflect

CRITICS SCOFFED BUT WOMEN BOUGHT: COCO CHANEL’S COMEBACK FASHIONS REFLECT THE DESIRES OF THE 1950S AMERICAN WOMAN By Christina George The date was February 5, 1954. The time—l2:00 P.M.1 The place—Paris, France. The event—world renowned fashion designer Gabriel “Coco” Cha- nel’s comeback fashion show. Fashion editors, designers, and journalists from England, America and France waited anxiously to document the event.2 With such high anticipation, tickets to her show were hard to come by. Some mem- bers of the audience even sat on the floor.3 Life magazine reported, “Tickets were ripped off reserved seats, and overwhelmingly important fashion maga- zine editors were sent to sit on the stairs.”4 The first to walk out on the runway was a brunette model wearing “a plain navy suit with a box jacket and white blouse with a little bow tie.”5 This first design, and those that followed, disap- 1 Axel Madsen, Chanel: A Woman of her Own(New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1990), 287. 2 Madsen, Chanel: A Woman of her Own, 287; Edmonde Charles-Roux, Chanel: Her Life, her world-and the women behind the legend she herself created, trans. Nancy Amphoux, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1975), 365. 3 “Chanel a La Page? ‘But No!’” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1954. 4 “What Chanel Storm is About: She Takes a Chance on a Comeback,” Life, March 1, 1954, 49. 5 “Chanel a La Page? ‘But No!’” 79 the forum pointed onlookers. The next day, newspapers called her fashions outdated. -

Gabrielle Chanel, Fashion Manifesto by Lili Tisseyre

www.smartymagazine.com Gabrielle Chanel, Fashion Manifesto by Lili Tisseyre >> PARIS While Paris Fashion Week is in full swing, far from the usual catwalks, the Palais Galliera, dedicated to fashion, offers a sublime retrospective that celebrates the allure and vision of Chanel. The exhibition, which opened last October, could not welcome the expected public due to (re)confinement and the tribute did not have the expected echo. In those years when Paul Poiret dominated women's fashion, Gabrielle Chanel, from 1912 onwards, in Deauville, then in Biarritz and Paris, revolutionized the world of couture, printing a true fashion manifesto on the bodies of her contemporaries. SEE THE VIDEO The scenography is chronological. In the first room of the exhibition, the curator has chosen to evoke the beginnings of Coco Chanel by highlighting a few emblematic pieces, including the famous jersey sailor jacket created in 1916. Then we are invited to follow the evolution of Chanel's chic style: from the little black dresses and sporty models of the Roaring Twenties to the sophisticated dresses of the 1930s. Further on, an entire room is devoted to N°5. The flagship perfume and quintessence of the spirit of "Coco" Chanel, this fragance is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. Dialoguing with the ten chapters dedicated to it, ten photographic portraits of Gabrielle Chanel punctuate the scenography and affirm how much the couturier still embodies the brand. Then came the war and the closure of the fashion house; the only thing that remained in Paris was the sale of perfumes and accessories at 31 rue Cambon. -

Teacher's Notes

For readers aged 4+ | 9781847807717 | Hardback | £9.99 Lots of the activities and discussion topics in these teacher’s notes are deliberately left open to encourage pupils to develop independent thinking around the book. This will help pupils build confidence in their ability to problem solve as individuals and also as part of a group. Little People, BIG DREAMS | teacher’s notes notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, 1 Little People, BIG DREAMS Teachers’ Notes © 2018 Frances Lincoln Children’s Books. All Rights Reserved. Written by Eva John. www.quartoknows.com The Front Cover What do you think Coco Chanel’s big dream might have been? Do you know anything about Coco Chanel? The Blurb Does the blurb suggest that your idea about Coco’s big dream was correct? Check your understanding of the following words and phrases: • orphanage • cabaret singer • seamstress • fashion designer • style icon If you are not quite sure, you could consult with friends, use a dictionary, or read the book to see if you can work it out for yourself. The Endpapers What effect does looking at the end papers have on you? Why do you think the illustrator decided on this design? This is the story of a young girl called Gabrielle. When she was little, Gabrielle lived in an orphanage. What is an orphanage? Who do you think ran the orphanage? What sort of childhood do you imagine Gabrielle had there? Little People, BIG DREAMS | teacher’s notes notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, 2 Little People, BIG DREAMS Teachers’ Notes © 2018 Frances Lincoln Children’s Books. -

“The Most Courageous Act Is Still to Think for Yourself. Aloud.” Coco Chanel

COCO CHANEL – MAVERICK TO ICON “The most courageous act is still to think for yourself. Aloud.” Coco Chanel Coco Chanel needs little introduction as a woman whose name has come to be synonymous with classic fashion and effortless style. During her lifetime she became the most famous female couturier in Europe and after her death was listed on the TIME’s 100 Most Influential People of the 20th Century. Few know the story behind the rise of the woman behind the interlocking CC emblem that represents the multibillion-dollar, privately owned luxury goods Chanel empire of today. What can we learn from this pioneering businesswoman that is relevant to this day? Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel was born 19th August 1883. Her mother was an unmarried laundry woman. Her father a nomadic street vendor. The couple had five children, including young Coco Chanel, all living in a crowded one-room lodging. When Chanel was just 12 years old, her mother died of tuberculosis. Her brothers were sent to work as farm labourers, and Chanel and her sisters were sent to the convent Aubazine which ran an orphanage in central France. It was in this frugal and austere period of her childhood that Chanel learned to sew, the skill that would make her an international fashion icon. At age 18 Chanel moved to a boarding house for Catholic girls in the town of Moulins. She sought work as a seamstress and in her free time sang in a cabaret bar frequented by cavalry officers. By the time she was 23, Coco had come to realise she would not have a serious stage career. -

Department of Art & Design

Whitburn Academy Department of Art & Design Art & Design Studies Learners Higher: Art & Design Studies Design Analyse the factors influencing designers and design practice by Booklet Fashion 1.1 Describing how designers use a range of design materials, techniques and technology in their work 1.2 Analysing the impact of the designers’ creative choices in a range of design work 1.3 Analysing the impact of social and cultural influences on selected designers and their design practice. A study of Coco Chanel Day dress, ca. 1924 Gabrielle Theater suit, 1938, Gabrielle Evening dress, ca. 1926–27 "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883–1971) "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883– Attributed to Gabrielle "Coco" Wool 1971) Silk Chanel (French, 1883–1971) Silk, metallic threads, sequins What is Fashion Design? Fashion design is a form of art dedicated to the creation of clothing and other lifestyle accessories. Modern fashion design is divided into two basic categories: haute couture and ready-to-wear. The haute couture collection is dedicated to certain customers and is custom sized to fit these customers exactly. In order to qualify as a haute couture house, a designer has to be part of the Syndical Chamber for Haute Couture and show a new collection twice a year presenting a minimum of 35 different outfits each time. Ready-to-wear collections are standard sized, not custom made, so they are more suitable for large production runs. They are also split into two categories: designer/creator and confection collections. Designer collections have a higher quality and finish as well as an unique design. They often represent a certain philosophy and are created to make a statement rather than for sale. -

THE SECTRET of for the First Time, a Couturier Revolu- Cionizes the Insular World of Perfume by Creating in 1921 Her Own Fragrance, the First of Its Kind

THE SECTRET OF For the first time, a couturier revolu- cionizes the insular world of perfume by creating in 1921 her own fragrance, the first of its kind. Coco Chanel seeks, in her own words, “ a woman’s perfume with a woman’s scent.” Her scent should be as important as her style of dress. Coco Chanel calls upon Ernest Beaux, perfumer to the Czars. In search of inspiration, Ernest Beaux ven- tures as far as the Arctic circle, finding his muse in the exhilarating air issuing from the northern lakes under the midnight sun. The couturier encourages him to be ever more audacious, demanding still more jasmine, the most precious of essences. He composes a bouquet of over 80 scents for her. An abstract, mysterious perfume radiaing an extravagance floral richness. For the first time, No5 transforms the alchemy of scent, through Ernest Beauxe’s innovtive use of al- dehydes, synthetic components which exalt perfumes, like lemon which accentuates the taste of strawberry. Aldehydes add layers of complexity, making No5 even more mysteri- ous and impsible to decipher. No5, a code, an identification number, makes the sentimental names for the perfumes of the day seem in- stantly out of date. It receives its name because Mademoiselle chanel prefers the fifth sample Ernes Beaux presents to her. For the first time, a perfume is presented in a simple laboratory flacon. From the United States to japan, the fragrance’s fame spreads, it soon becomes the best-selling perfume in the world. No5 pioneers a new form of advertising in the world of fragrance. -

28 March – 13 September 2015

KARL LAGERFELD. MODEMETHODE 28 March – 13 September 2015 Karl Lagerfeld is one of the world’s most renowned fashion designers and widely celebrated as an icon of the zeitgeist. Karl Lagerfeld. Modemethode at the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany is the first comprehensive exhibition to explore the fashion cosmos of this exceptional designer and, with it, to present an important chapter of the fashion history of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Karl Lagerfeld is known for injecting classic shapes with new life and for taking fashion into new directions. For the past sixty years – from 1955 to today – Lagerfeld’s creations have consistently demonstrated his extraordinary feel for the ‘now’. Right from the start of his career, the designer has worked for luxury houses such as Balmain, Patou, Fendi, Chlo, Karl Lagerfeld and Chanel. As creative director and chief designer of Chanel since 1983, he is regarded among experts as the sole legitimate successor to the founder and fashion legend Coco Chanel. Since 1965 Lagerfeld has been designing two – of late even four – collections per year for the Italian house of Fendi, not to mention his own eponymous label. Karl Lagerfeld is celebrated as a fashion genius not only for continuously revitalising classics like the Chanel suit, but also for endlessly reinventing himself. Having realised by the early 1960s that the future of fashion could not lie in haute couture alone, Lagerfeld embraced the younger ready-to-wear (prt-- porter) lines: ‘Fashion that does not reach the streets is not fashion’ (Lagerfeld). In addition to clothing, Lagerfeld designs a wide range of accessories to accompany his collections. -

Fashion in an Age of Technology

MANUS X MACHINA: FASHION IN AN AGE OF TECHNOLOGY INTRODUCTION The traditional distinction between the haute couture and prêt-à-porter has always been between the custom-made and the ready-made. Haute couture clothes are singular models fitted to the body of a specific individual, while prêt-à-porter garments are produced in multiples for the mass market in standard sizes to fit many body types. Implicit in this difference is the assumption that the handwork techniques involved in the haute couture are superior to the mechanized methods of prêt-à-porter. Over the years, however, each discipline has regularly embraced the practices of the other. Despite the fact that this mutual exchange continues to accelerate, the dichotomy between the hand (manus) and the machine (machina) still characterizes the production processes of the haute couture and prêt-à-porter in the twenty-first century. Instead of presenting the handmade and the machine-made as oppositional, this exhibition suggests a spectrum or continuum of practice, whereby the hand and the machine are equal and mutual protagonists in solving design problems, enhancing design practices, and, ultimately, advancing the future of fashion. It prompts a rethinking of the institutions of the haute couture and prêt-à-porter, especially as the technical separations between the two grow increasingly ambiguous and the quality of designer prêt-à-porter more refined. At the same time, the exhibition questions the cultural and symbolic meanings of the hand-machine dichotomy. Typically, the hand has been identified with exclusivity and individuality as well as with elitism and the cult of personality. -

Fashioning Coco Chanel Sarah Wiggins Bridgewater State College, [email protected]

Bridgewater Review Volume 34 | Issue 1 Article 12 May-2015 Book Review: Fashioning Coco Chanel Sarah Wiggins Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Recommended Citation Wiggins, Sarah (2015). Book Review: Fashioning Coco Chanel. Bridgewater Review, 34(1), 35-36. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol34/iss1/12 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. suits, or schoolboy sports clothes and BOOK REVIEWS blazers, the ‘Chanel woman’ conjured the silhouette of the war’s millions of Fashioning Coco Chanel soldiers – the young men dying just out Sarah Wiggins of sight of the general population” (87). Unfortunately, as the book contin- Rhonda K. Garelick, Mademoiselle: Coco Chanel and ues, the figure of Chanel is lost to the the Pulse of History (New York: Random House, reader. Garelick structures individual chapters on Chanel’s romantic inter- 2014). ests, including the exiled Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, poet pectators are drawn to the grandeur of a Chanel Pierre Reverdy, the wealthy Duke of runway performance, captivated by the clothing Westminster, and French illustrator design, models, and theatrical staging. Embedded and nationalist, Paul Iribe. There is one S chapter dedicated to her female friend- in the drama of a Chanel show is the vision of its ships, in particular with society force, original founder, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel (1883- Misia Sert, but the majority of writing focuses on her male companions. In her 1971). When we hear the term “Chanel,” we think of quest to discover what these relation- the Chanel suit, strings of pearls, the little black dress, ships “might offer beyond their anec- and basic, classic style. -

Hemmerle Bangle in Ebony, Iron, Silver and White Gold Set with Diamonds. POA

Hemmerle Bangle in ebony, iron, silver and white gold set with diamonds. POA. www.hemmerle.com Ring with one 3.10-carat emerald-cut diamond set on Lucite or acrylic glass (nothing else is involved in this extraordinary creation, where the diamond and synthetic material just seamlessly merge together) by Theodoros Savopoulos “Challenging the borders of creativity www.instagram.com/theodoros_jeweler has been my aim and I have come to realise that new design is not necessarily limited to new forms, but it can also be achieved with new materials”, There is a sense of reaching towards some- Theodoros Savopoulos notes thing new or is it déjà vu? In any case, the resurgence of jewellery made with metals other than gold could certainly be labelled as a back-to-the-future phenomenon. Some forward-thinking private jewellers, famous for their high jewellery credentials, have in- deed been toying with unconventional alloys or common metals that have an industrial or domestic application (aluminium, steel, copper or iron, etc). In what could be seen as a bold move that reconciles low and high- brow materials, these practitioners keep ex- ploring the physical potential of those met- als in order to broaden their creative scope. “Different philosophies and approaches to making jewellery can affect the choice of metals used. For many jewellers today, luxury does not mean the largest diamond or gold or platinum; true luxury lies in the craftsman- ship, the design, the artistic sensibility. It di- rects itself more to aesthetics and less to the value inherent in a metal”, Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos head of Mahnaz Collection adds.