The Mystery of the Purr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feline Leukemia Virus and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus, Important Information for Cat Lovers

KAR Friends June 2012 Dear Reader, Summer is here and with it -- warm weather and fun in the sun! This month we bring you some fun facts about dogs and cats. Our Ask the Vet column addresses the Feline Leukemia Virus and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus, important information for cat lovers. Doggie Den provides some helpful tips for improving your canine’s table manners, and Cat’s Corner shares the happy adoption story of two cats with feline leukemia that found the perfect forever home. Danielle Wallis Lynn Bolhuis Marketing Coordinator KAR Friends Editor P.S. Our special Spring Edition newsletter was mailed last week. This issue has more great rescue and adoption stories, and you can view it right here. Pet Fun Facts It’s A Hairy World Out There By Kerrie Jo Harvey IN THIS ISSUE… The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be Pet Fun Facts judged by the way its animals are treated. ~ Ghandi Ask the Vet ~ FeLV and FIV Did you know that when it comes to Doggie Den ~ Dog having pets, the United States is first Table Manners among nations for having the most four-legged critters as family Cats Corner ~ A Tale of members? According to pet Two Kitties population data posted on the Mapsofworld.com website, American families have 61,080,000 dogs in their households. Not that we like to brag or anything, but the US has twice the number of Brazil, who fills second place with 30,051,000 canines. Perhaps this means that American families are twice as fortunate when it comes to enjoying the companionship and loyalty of man’s best friend. -

Ectoparasites of Free-Roaming Domestic Cats in the Central United States

Veterinary Parasitology 228 (2016) 17–22 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vetpar Research paper Ectoparasites of free-roaming domestic cats in the central United States a b,1 a a,∗ Jennifer E. Thomas , Lesa Staubus , Jaime L. Goolsby , Mason V. Reichard a Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, Center for Veterinary Health Sciences, Oklahoma State University, 250 McElroy Hall Stillwater, OK 74078, USA b Department of Clinical Science, Center for Veterinary Health Sciences, Oklahoma State University, 1 Boren Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital Stillwater, OK 74078, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Free-roaming domestic cat (Felis catus) populations serve as a valuable resource for studying ectoparasite Received 11 May 2016 prevalence. While they share a similar environment as owned cats, free-roaming cats do not receive rou- Received in revised form 27 July 2016 tine veterinary care or ectoparasiticide application, giving insight into parasite risks for owned animals. Accepted 29 July 2016 We examined up to 673 infested cats presented to a trap-neuter-return (TNR) clinic in the central United States. Ectoparasite prevalences on cats were as follows: fleas (71.6%), ticks (18.7%), Felicola subrostratus Keywords: (1.0%), Cheyletiella blakei (0.9%), and Otodectes cynotis (19.3%). Fleas, ticks, and O. cynotis were found in Cat all months sampled. A total of 1117 fleas were recovered from 322 infested cats. The predominate flea Feline recovered from cats was Ctenocephalides felis (97.2%) followed by Pulex spp. -

Think Twice Before You Declaw

This article first appeared in the Winter 2006 issue of Animal Behavior Consulting: Theory and Practice, a publication of the International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants, www.iaabc.org. Copyright 2006 The IAABC. Think Twice Before You Declaw The Itch to Scratch Cats do write. They don’t communicate Asking a cat never to scratch with a pen and paper or by using a com- is asking a cat not to act like puter keyboard. Instead, their prose is cat a cat. scratch—literally. They scratch to express their excitement and pleasure. They Most of us don’t mind that scratch to leave messages, both visual and cats scratch; what bothers us aromatic. (A cat’s paws have scent glands is where they scratch. But that leave smell-o-grams; we can’t read nearly all cats can be taught them, but other cats can.) where to scratch—and where not to. Kittens are Cats also scratch, not to sharpen their nails particularly easy to train, but to remove the worn-out sheaths from but it’s not that difficult to their claws. You see the results as little cres- teach the adults, either. The cent-moon shaped bits around scratching secret is to provide attractive areas. Scratching is good exercise, too. scratching alternatives to the sofa or stereo speakers and Scratching is normal behavior for cats. then teach the cat to use those alternatives. All cats scratch; it’s part of being a cat. Reality Check Just so you know, a typical declaw on a cat who goes outdoors, since de- (called an onychectomy) is an irre- clawed cats have been disarmed. -

Vet FF 1990A.Pdf (851.4Kb)

Feline Forum Courtesy of: FIV Threatens Health of Cats Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) Diagnosis is based on the cat’s his can prescribe drugs to control secon is a newly recognized feline virus. tory, clinical signs, and results of an dary infections, inflammatory conditions Although it is in the same family of FIV-antibody test. A positive FlV-anti- such as gingivitis, and weight loss. viruses (retroviruses) as feline leuke body test indicates that a cat is infected Currently, there is no vaccine available mia virus, FIV does not cause cancer with FIV. It is recommended that FIV- to protect cats against FIV infection. and is not classified in the same sub positive cats have no contact with non family of retroviruses as feline leuke infected cats. If a cat is infected with mia. FIV is in the lentivirus subfamily, FIV there is no drug that will cure the along with the viruses causing pro disease. However, your veterinarian gressive pneumonia in sheep, infec tious anemia in horses and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in humans. (Although FIV is structurally Vaccinate Your Cat similar to AIDS, it is a highly species- The incidence of feline infectious How Do specific agent. There has been no evi diseases has been reduced significantly dence of human infection from FIV, or through the use of vaccines. Vaccines Cats Purr? vice versa.) contain adjuvants (substances that enhance the immune response) and The primary mode of transmission the infectious agent either as modified One scientific theory states that of FIV is unknown, but bite wounds are live or inactivated. -

Check List: for a Healthy Cat

CHECK LIST: FOR A HEALTHY CAT Congrats on your new pet! This welcome kit is a great reference for tips from Cascade Pet Hospital on how to keep your kitty healthy and happy. NECESSITIES OTHER SUGGESTED ITEMS • Premium Grade Food • Cat Treats for Training and Play, with or without Catnip • Bowls - Ceramic or Stainless Steel for Food & Water (Cats are Prone • Air-Tight Food Container & Scoop to Plastic Allergies) • Regular Grooming Program Cat • Litter Box & Litter (1 per Cat, Plus Bed 1 Additional in Multi-Cat Homes) • Change or Scoop Litter Daily • ID Tag & Microchip Safe • Books on Cat Care (breed specific) • Toys • Litter Genie • Pet Carrier (Appropriate for Size) • De-Shedding Tool • Stain Remover & Odor Eliminator (Do Not Use Ammonia) • Vertical Cat Tree • Flea Comb & Flea & Tick Control Products • Toothbrush Kit & Dental Aids (TD, CET Chews, etc.) • Bi-Yearly Exam with your Veterinarian DAILY PET CHECK: FOR A HEALTHY CAT MY PET • Is acting normal, active and happy. • Does not tire easily after moderate exercise. Does not have seizures or fainting episodes. • Has a normal appetite, with no significant weight change. Does not vomit or regurgitate food. • Has normal appearing bowel movements (firm, formed, mucus-free). Doesn’t scoot on the floor or chew under the tail excessively. • Has a full glossy coat with no missing hair, mats or excessive shedding. Doesn’t scratch, lick or chew excessively. • Has skin that is free of dry flakes, not greasy, and is odor-free. Is free from fleas, ticks or mites. • Has a body free from lumps and bumps. Has ears that are clean and odor-free. -

Pet Care Tips for Cats

Pet Care Tips for cats What you’ll need to know to keep your companion feline happy and healthy . Backgroun d Cats were domesticated sometime between 4,000 and 8,000 years ago, in Africa and the Middle East. Small wild cats started hanging out where humans stored their grain. When humans saw cats up close and personal, they began to admire felines for their beauty and grace. There are many different breeds of cats -- from the hairless Sphinx and the fluffy Persian to the silvery spotted Egyptian Mau . But the most popular felines of all are non-pedigree —that includes brown tabbies, black-and-orange tortoiseshells, all-black cats with long hair, striped cats with white socks and everything in between . Cost When you first get your cat, you’ll need to spend about $25 for a litter box, $10 for a collar, and $30 for a carrier. Food runs about $170 a year, plus $50 annually for toys and treats, $175 annually for litter and an average of $150 for veterinary care every year. Note: Make sure you have all your supplies (see our checklist) before you bring your new pet home. Basic Care Feeding - An adult cat should be fed one large or two or three smaller meals each day . - Kittens from 6 to 12 weeks must eat four times a day . - Kittens from three to six months need to be fed three times a day . You can either feed specific meals, throwing away any leftover canned food after 30 minutes, or keep dry food available at all times. -

Therisksofupperrespiratoryinfe

® Expert information on medicine, behavior andhealth from a world leader in veterinary medicine INSIDE The Risks ofUpper Respiratory Infedions Short Takes 2 Ocean-going farewells; ahealth They're often ultimately harmless, but kittens are especially bene~\t \)~ pet \)\fm~C)h\p. vulnerable, and secondary diseases can have serious effects ADeadly Threat to Outdoor Cats 3 Hypothermia can cause adrop in igns that your cat • The infections can be blood pressure and cardiac arrest. Shas an infection of highly communicable in his upper respiratory multi-cat households. The first Oue: a Persistent Cough 4 tract can mimic the Unfortunately, vac Wheezing and breathing through the ones you suffer with cines for respiratory tract mouth are also hallmarks of asthma. a cold: watery eyes, infections don't provide Ask Elizabeth 8 runny nose, wheezing, total protection, although sneezing and coughing. they can reduce the illness' Chewing and scratching hot spots Just as you're likely to length and severity. About will perpetuate the damage. rebound in a few days, 80 percent of feline up ------------4 in most instances a cat per respiratory infections IN THE NEWS ••• will, too. ~ are caused by one of two In some cases, how ~ viruses: feline herpesvirus 'Kitty cams' reveal ever, bacterial and viral in (FRV), also known as their hidden world respiratory infections can carry Significant risks: feline rhinotracheitis virus (FRV), and feline • Complications such as pneumonia, calicivirus (FCV). A third and far less fre Two thousand hours of video blindness or chronic breathing problems quent cause of upper respiratory infections in recorded by "kitty cams" from the can develop. -

The Cat's Meow Is Her Way of Communicating with People

Meowing and Yowling The cat’s meow is her way of communicating with people. Cats meow for many reasons—to say hello, to ask for things and to tell us when something’s wrong. Meowing is an interesting vocalization because adult cats don’t actually meow at each other, just at people. Kittens meow to let their mother know they’re cold or hungry, but once they get a bit older, cats no longer meow to other cats. But they continue to meow to people throughout their lives, probably because meowing gets people to do what they want. Cats also yowl—a sound similar to the meow but more drawn out and melodic. Although they don’t meow, adult cats do yowl at one another, specifically during the breeding season. When does meowing become excessive? That’s a tough call to make, as it’s really a personal issue. All cats are going to meow to some extent—this is normal communication behavior. But some cats meow incessantly and drive their pet parents crazy! Bear in mind that some cat breeds, notably the Siamese, are prone to excessive meowing and yowling. Why Cats Meow These are the most common reasons why cats meow: • To greet people You can expect your cat to meow in greeting when you come home, when she meets up with you in the house or yard, and when you speak to her. • To get attention Cats enjoy social contact with people, and some will be quite vocal in their requests for attention. Your cat might want you to stroke her, play with her or simply talk to her. -

Catnip Anyone? by Dawn Pettinelli, Uconn Home & Garden Education Center

Catnip Anyone? By Dawn Pettinelli, UConn Home & Garden Education Center Most plants we grow, indoors or out, are either useful to us, like vegetables, or attractive additions to our gardens and landscapes. One plant your pet cat will thank you for growing is catnip (Nepeta cataria). Catnip is a perennial member of the mint family native to parts of Asia and Europe. Like most mints, it is fairly easy to grow. If anything, mints are rather boisterous plants, always looking to expand their range, especially given their preferred conditions of sun and plenty of moisture. They can be restrained to some degree by growing them in partly shaded, drier parts of the garden. In the case of catnip, given a sunny window, it is perfectly happy to be grown as a houseplant, which is how I grow it for our inside cat. The scalloped-edged, pointy leaves are an attractive medium green and slightly hairy on the undersides. Stems are characteristically square. If grown outside, plants usually bloom once during the summer. The flowers are small and white with purple spots. Like all mints, they are attractive to honeybees and other pollinators. Catnip is easily grown from seed and will self-seed if the flowers are left to mature on the plant so remove them after blooming if this is not a desirable trait. A cat’s response to catnip may vary but can include rubbing or rolling on the plant, sniffing, licking, chewing on the leaves, vocalizing, drooling as well as other crazy antics. It’s not just domestic felines that find catnip alluring; big cats too are drawn to this aromatic herb. -

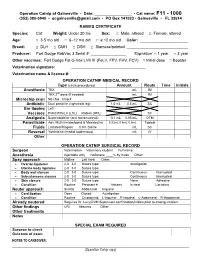

Operation Catnip Medical Records

Operation Catnip of Gainesville • Date: _________________ • Cat name: F11 - 1000 (352) 380-0940 • [email protected] • PO Box 141023 • Gainesville • FL 32614 RABIES CERTIFICATE Species: Cat Weight: Under 20 lbs Sex: □ Male, altered □ Female, altered Age: □ 3-5 mo old □ 6–12 mo old □ ≥ 12 mo old Color: ______________________ Breed: □ DLH □ DMH □ DSH □ Siamese/pointed ____________________________ Producer: Fort Dodge RabVac 3 Serial #: ________________ Expiration: □ 1 year □ 3 year Other vaccines: Fort Dodge Fel-O-Vax LVK III (FeLV, FPV, FHV, FCV) □ Initial dose □ Booster Veterinarian signature: __________________________________ Veterinarian name & license #: __________________________________ OPERATION CATNIP MEDICAL RECORD Type (circle procedures) Amount Route Time Initials Anesthesia TKX mL IM TKX 2nd dose (if needed) mL IM Microchip scan No chip Chip # Antibiotic Dual penicillin (right front leg) 1.0 mL 0.5 mL SC Ear tipping Left Vaccines FVRCP/FeLV (LHL) Rabies (RHL) SC Analgesia Buprenorphine (oral transmucosal) 0.1 mL 0.05 mL OTM Parasiticide Adv. Multi (Imidacloprid & Moxidectin) 0.23mL 0.4mL 0.8mL Topical Fluids Lactated Ringers 0.9% Saline mL SC Reversal Yohimbine (medial saphenous) mL IV Other OPERATION CATNIP SURGICAL RECORD Surgeon Veterinarian Veterinary student Full name: Anesthesia Injectable only Isoflurane ____% by mask Other: Spay approach Midline Left flank Other: Ovarian ligatures 2-0 3-0 Suture type: Autoligation Uterine body ligatures 2-0 3-0 Suture type: Body wall closure 2-0 3-0 Suture type: Continuous Interrupted Subcutaneous closure 2-0 3-0 Suture type: Continuous Interrupted Skin closure 2-0 3-0 Suture type: None Adhesive Condition Routine Pregnant #_______ fetuses In heat Lactating Neuter approach Scrotal Abdominal Inguinal Cord ligation Open Closed Autoligation Condition Routine Cryptorchid: L-Inguinal R-Inguinal L-Abdominal R-Abdominal Already neutered Requires Dr. -

Catnip Recipes 21

1 Letter from the Publisher Catnip is an herb that I love to use with kids and people who are highly sensitive to calming nervines. It is a main ingredient in my Calm Kid tea recipe, which is quite popular with my clients and customers at farmers markets. Every time someone unfamiliar with medicinal herbs looks at the ingredients, I get the same reaction: “Catnip! That makes cats crazy! How is it calming?” Well, as it turns out the nervous systems of cats and humans are different, and while the terpenoid nepetalactone makes 70–80% of cats wacky, it is a relaxant and mild sedative to humans. Not only is it a calming nervine that is wonderfully gentle for kids, it is also a well-known digestif and helps to reduce flatulence, cramps, and colic. It is quite gentle, and therefore perfect to use with young children; it’s a must-have for teething, screaming, and spasms related to crying fits. You know the ones, where the child’s body bows backward, their thighs and arms tighten, and they won’t let you soothe or cuddle them into feeling better? Being a part of the mint family, it is quite easy to grow and is often found growing rogue in waste areas, near water runoff, and around the ruins of long-gone homesteads. Many herbalists believe that the plants most common around us are meant to be our most-used medicine. Perhaps that is why catnip is so simple to grow and so widely distributed and used. We all need a little bit of calm in our lives. -

The Behaviour of the Domestic Cat, Second Edition

12 Physiological and Pathological Causes of Behavioural Change Introduction Overt behaviour is the consequence of a cat perceiving some change in its environment, evaluating this change, deciding on an appropriate response and the response being generated through the motor systems of the brain to the elements of the skeletal system that control activity. Hence, although behaviour occurs as a consequence of changes in the external environment, the responses generated also depend on internal variations in the processing of information. These processes are susceptible to alteration due not only to normal physiological variations but also to pathological changes. Interpretation of behaviour, therefore, requires an understanding of how the generation of behaviour is modulated by factors influencing the internal state, as well as how responses are generated to events in the external environment. Pathological changes can be the sole cause of behavioural change – indeed, behavioural signs such as lameness are common first indicators of disease in veterinary medicine. In some cases complex behavioural signs, such as aggressive behaviour towards an owner, can occur entirely as a consequence of pathological events, such as focal seizures. Although such events are rare, their characteristics need to be distinguished from behaviours generated in response to external stimuli when investigating the cause of undesired behaviours. However, physiological or pathological changes more commonly modify cats’ behaviour rather than solely cause it. This is through alterations in one or more of the following: (i) perception of external events; (ii) the motivation to show a response; (iii) the threshold at which a response is shown; and (iv) the manner in which a response is generated.