Monopoly and Competition, and at the Same Time to Give an Analysis of English Cartels and Trusts As They Now Are

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monopolists Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the Worlds Favorite Board Game 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE MONOPOLISTS OBSESSION, FURY, AND THE SCANDAL BEHIND THE WORLDS FAVORITE BOARD GAME 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Pilon | 9781608199631 | | | | | The Monopolists Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the Worlds Favorite Board Game 1st edition PDF Book The Monopolists reveals the unknown story of how Monopoly came into existence, the reinvention of its history by Parker Brothers and multiple media outlets, the lost female originator of the game, and one man's lifelong obsession to tell the true story about the game's questionable origins. Expand the sub menu Film. Determined though her research may be, Pilon seems to make a point of protecting the reader from the grind of engaging these truths. More From Our Brands. We logged you out. This book allows a darker side of Monopoly. Cannot recommend it enough! Part journalist, part sleuth, Pilon exhausted five years researching the game's origin. Mary Pilon's page-turning narrative unravels the innocent beginnings, the corporate shenanigans, and the big lie at the center of this iconic boxed board game. For additional info see pbs. Courts slapped Parker Brothers down on those two games, ruling that the games were clearly in the public domain. Subscribe now Return to the free version of the site. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. After reading The Monopolists -part parable on the perils facing inventors, part legal odyssey, and part detective story-you'll never look at spry Mr. Open Preview See a Problem? The book is superlative journalism. Ralph Anspach, a professor fighting to sell his Anti-Monopoly board game decades later, unearthed the real story, which traces back to Abraham Lincoln, the Quakers, and a forgotten feminist named Lizzie Magie who invented her nearly identical Landlord's Game more than thirty years before Parker Brothers sold their version of Monopoly. -

Part I: Introduction

Part I: Introduction “Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.” -Thomas Paine, Common Sense (1776) “For my part, whatever anguish of spirit it may cost, I am willing to know the whole truth; to know the worst and provide for it.” -Patrick Henry (1776) “I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth. On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen -- but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue leap from its pedestal, and to hasten the resurrection of the dead.” -William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator (1831) “Gas is running low . .” -Amelia Earhart (July 2, 1937) 1 2 Dear Reader, Civilization as we know it is coming to an end soon. This is not the wacky proclamation of a doomsday cult, apocalypse bible prophecy sect, or conspiracy theory society. -

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game in 1934, Charles B

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game In 1934, Charles B. Darrow of Germantown, Pennsylvania, presented a game called MONOPOLY to the executives of Parker Brothers. Mr. Darrow, like many other Americans, was unemployed at the time and often played this game to amuse himself and pass the time. It was the game’s exciting promise of fame and fortune that initially prompted Darrow to produce this game on his own. With help from a friend who was a printer, Darrow sold 5,000 sets of the MONOPOLY game to a Philadelphia department store. As the demand for the game grew, Darrow could not keep up with the orders and arranged for Parker Brothers to take over the game. Since 1935, when Parker Brothers acquired the rights to the game, it has become the leading proprietary game not only in the United States but throughout the Western World. As of 1994, the game is published under license in 43 countries, and in 26 languages; in addition, the U.S. Spanish edition is sold in another 11 countries. OBJECT…The object of the game is to become the wealthiest player through buying, renting and selling property. EQUIPMENT…The equipment consists of a board, 2 dice, tokens, 32 houses and 12 hotels. There are Chance and Community Chest cards, a Title Deed card for each property and play money. PREPARATION…Place the board on a table and put the Chance and Community Chest cards face down on their allotted spaces on the board. Each player chooses one token to represent him/her while traveling around the board. -

Anti-Monopoly, Inc. V. General Mills Fun Group, Inc.: Ending the Monopoly on Monopoly

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 17 Number 4 Article 6 9-1-1984 Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. General Mills Fun Group, Inc.: Ending the Monopoly on Monopoly Thomas J. Daly Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas J. Daly, Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. General Mills Fun Group, Inc.: Ending the Monopoly on Monopoly, 17 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 1021 (1984). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol17/iss4/6 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANTI-MONOPOL Y, INC. v. GENERAL MILLS FUN GROUP, INC.: ENDING THE MONOPOLY ON "MONOPOLY" I. INTRODUCTION In Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. GeneralMills Fun Group, Inc. (4nti-Mo- nopoly I1),1 the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the trade- mark registration of MONOPOLY2 for Parker Brothers' popular real estate board game was invalid because the term had become "ge- neric."3 This followed an earlier decision by the Ninth Circuit in the same case Qinti-Monopoly J),4 which set out the basic test to be used to determine if MONOPOLY was "generic." These decisions have received criticism from commentators 5 and trademark lawyers,6 have provoked alarm among trademark owners,7 and have prompted political activity aimed at amending the Lanham Trademark Act.' This response is due to the court's departure from 1. -

Anti-Monopoly Law

October 2002 China’s Draft Anti-Monopoly Law Paul, Weiss has recently obtained a draft of the Anti-Monopoly Law (the "AML") of the People's Republic of China ("PRC" or "China") dated February 26, 2002. We attach for your information the Paul, Weiss translation of the draft AML, and provide in this memorandum an initial analysis of the draft AML and other PRC statutes related to anti-monopoly review and regulation. The current draft is apparently not the final version, but as the AML has been in the drafting process since 1994, we believe it represents something close to the principles that will be reflected in the legislation if and when it is finally adopted. I. Outline of the AML A. General The AML governs three types of activities: (a) "activities restricting competition in market transactions" within China, (b) the "abuse of administrative powers to restrict competition" within China, and (c) activities outside China that violate the AML and that restrict or affect competition within China.1 In general, it regulates the activities of "operators," defined in Article 4 to mean legal persons and other organizations and individuals engaged in the production and operation of commodities or services. Article 4 further states that the term "commodities" under the AML includes services. Finally, "market" for purposes of the AML means a geographical area within which operators compete with respect to a given commodity over a certain period of time.2 A key element of the AML is its provision in Chapter 6 for the establishment of a new government agency charged with enforcement. -

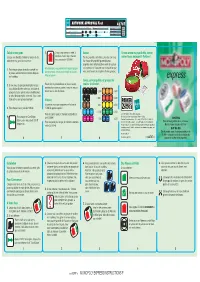

MONOPOLY EXPRESS INSTRUCTIONS F MONOPOLY 101 Hasbro Design Centre (STU) Design Centre Hasbro

ITEM CODE First 42787 Artwork Originator: Hasbro Design Centre (STU) File Name: Express Instructions 101 Line Year: 2005 APPLY Artwork Start: 19.05.05 APPROVAL Product: Monopoly Express LID BASE CARTON GAMEBOARD RULES NOTE Repro Start: 00.05.05 Instructions CARDS DIECUT SHEET DECALS HERE! Calcul de vos gains 5. Si vous avez obtenu un hôtel, à Astuce Si vous aimez les jeux de dés, tentez Lorsque vous décidez d'arrêter les lancers de dés, condition d’avoir déjà 4 maisons, Plus les propriétés sont chères, plus elles sont rares. votre chance en jouant à Yahtzee ! € additionnez vos gains durant ce tour : vous avez touché 5 000 . Sur chaque dé propriété figurent plusieurs propriétés alors réfléchissez-bien avant de le placer sur le plateau, car il pourrait vous manquer lorsque 1. Pour chaque groupe de couleur complet sur N’oubliez pas, vous perdez tout l’argent gagné vous aurez besoin de compléter d'autres groupes. le plateau, additionnez les montants indiqués durant ce tour, si vous avez rempli les 3 cases sur le plateau. Allez en prison. express Gares, services publics et groupes de 2. Si vous avez des groupes incomplets lorsque Passez alors la piste de lancer au joueur suivant, couleur à collecter : vous décidez d’arrêter votre tour, choisissez le remettez les maisons au centre si vous en avez, et groupe de la plus grande valeur et additionnez retirez tous les dés du plateau. = 2 500 = 1 800 la valeur de chaque dé à votre total. Vous n’avez droit qu’à un seul groupe incomplet. Victoire = 800 = 2 200 Le premier joueur qui empoche une fortune de = 600 = 2 700 3. -

Korea - the Role of Competition Policy in Regulatory Reform 2000

Korea - The Role of Competition Policy in Regulatory Reform 2000 The Review is one of a series of country reports carried out under the OECD’s Regulatory Reform Programme, in response to the 1997 mandate by OECD Ministers. This report on the role of competition policy in regulatory reform analyses the institutional set-up and use of policy instruments in Korea. This report was principally prepared by Mr. Michael Wise for the OECD. BACKGROUND REPORT ON THE ROLE OF COMPETITION POLICY IN REGULATORY REFORM* * This report was principally prepared by Michael Wise in the Directorate for Financial and Fiscal Affairs of the OECD. It has benefited from extensive comments provided by colleagues throughout the OECD Secretariat, by the Government of Korea, and by Member countries as part of the peer review process. This report was peer reviewed in October 1999 in the OECD’s Competition Law and Policy Committee. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. FOUNDATIONS OF COMPETITION POLICY 2. SUBSTANTIVE ISSUES: CONTENT OF THE COMPETITION LAW 3. INSTITUTIONAL ISSUES: ENFORCEMENT STRUCTURES AND PRACTICES 4. LIMITS OF COMPETITION POLICY: EXEMPTIONS AND SPECIAL REGULATORY REGIMES 5. COMPETITION ADVOCACY FOR REGULATORY REFORM 6. CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY OPTIONS BIBLIOGRAPHIE Tables 1. Actions against abuse of dominance 2. Korean industries with “market-dominant enterprises” 3. Trends in competition policy resources 4. Trends in competition policy actions 2 Executive Summary Background Report on The Role of Competition Policy in Regulatory Reform Competition policy must be integrated into the general policy framework for regulation. Competition policy is central to regulatory reform, because its principles and analysis provide a benchmark for assessing the quality of economic and social regulations, as well as motivate the application of the laws that protect competition. -

Toward a New Model for US Telecommunications Policy

Adjusting Regulation to Competition: Toward a New Model for U.S. Telecommunications Policy t Howard A. Shelanski This Article explains the monopoly rationalefor conventional approaches to telecommunications regulation, demonstrates how the U.S. telecommunications market has changed since the Telecommunications Act of 1996, and then examines whether, in the light of those changes, the conventional approach remains an appropriate paradigm for U.S. telecommunications policy. This Article finds that the general answer is no, and that ex ante regulation that depends for its rationale on monopoly market structure should give way to ex post intervention against specific, anti- competitive acts on the model of conventional antitrust and competition policy. The Article finds, however, that certain kinds of regulation-notably interconnection-still have a role to play in advancing telecommunications policy objectives. This study's conclusions thus challenge the argument that policymakers should wait until market conditions become more competitive to deregulate. But it also challenges claims that the market has developed to the point that Congress should eliminate all industry-specific regulation and regulatory authority in the U.S. telecommunications market. This Article insteadproposes eliminating ex ante regulation that depends on monopoly for its rationale in favor of ex post competition enforcement, but makes allowance for other regulation in those specific circumstances where experience proves such intervention necessary and effective for protectingconsumer -

42749 Rules Monopoly

HOTELS If you owe the Bank more than you can pay, even by selling off buildings and mortgaging property, You must have four houses on each property of a you must turn over all assets to the Bank. The Bank complete color-group before you can buy a hotel. You will immediately auction all property so taken, may then buy a hotel from the Bank to be built on any except buildings. property of that color-group. Remove your token from the board once bankruptcy To build a hotel, you must ask the Bank to exchange the proceedings are completed. four houses on the chosen property for a hotel as well as make the payment printed on the Title Deed. WINNING It can be very advantageous to build hotels because very The last player remaining in the game wins. large rents are charged for them. ONLY ONE HOTEL MAY BE BUILT ON ANY ONE ABRIDGED VERSIONS OF THE GAME PROPERTY. Short Game (60 to 90 Minutes) SELLING PROPERTY There are five changed rules for this version of the game: ® Undeveloped properties, railroads and utilities (but 1. During PREPARATION, the Banker shuffles then not buildings) may be sold to any player as a private deals three Title Deed cards to each player. These transaction for a sum agreeable to the owner. No property, BRAND are free – no payment to the Bank is required. Property Trading Game from Parker Brothers ® however, may be sold to another player if any buildings 2. You need only three houses (instead of four) on each stand on any property of that color-group. -

Monopoly: a Game of Strategy…Or Luck? EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Serene Li Hui Heng , Xiaojun Jiang , Cheewei Ng, Li Xue Alison Then Team 5, MS&E220 Autumn 2008

Monopoly: A Game of Strategy…Or Luck? EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Serene Li Hui Heng , Xiaojun Jiang , Cheewei Ng, Li Xue Alison Then Team 5, MS&E220 Autumn 2008 A popular board game since 1935, Monopoly is a game that may be dependent on both luck and strategy. A player can bet on his or her own luck alone, think carefully and buy up strategic properties, or use strategy to complement his or her luck to gain dominance in the game. Our report seeks to present our findings on the importance of strategy in Monopoly, as well as which strategies are the most successful. So is Monopoly a game of strategy, or luck, or both? Our methodology involved examining the inter-relationships between the various factors in the game, for example, the throw of the 2 dice, the number of throws that a player has played, the number of rounds he is in, accounting for jail and rent etc. After establishing the inter-relations, we built up our model by gradually adding more factors (which increase uncertainty) that affect the game, and thereby incorporated more realism into the model. We thus proceeded to build 3 main models, by using dynamic equations. First we used the propagation of probability flow method to determine the chances of landing on a particular square in a given number of throws (Model 1). Next, we included regeneration points in the case where jail is considered (Model 2). Lastly, from the probability flow sequences obtained, we calculated the expected value of landing on each square on the board, taking into account the rents paid and $200 that a player gets each time after he passes a round, to analyze the wealth effect when multiple players are involved (Model 3). -

DO NOT PASS GO: PATENTS, TRADEMARKS, and “MONOPOLY” Research Report for WR227 Sinnett, James Winter Term, 2018

Sinnett, James DO NOT PASS GO: PATENTS, TRADEMARKS, AND “MONOPOLY” Research Report for WR227 Sinnett, James Winter Term, 2018 1 Sinnett, James Table of Contents Table of Contents.............................................................................................................................2 Introduction......................................................................................................................................3 Developing the Property..................................................................................................................3 Elizabeth Magie..........................................................................................................................3 Charles Darrow...........................................................................................................................4 Developing a Monopoly..................................................................................................................5 Anti-Monopoly................................................................................................................................5 Genericide........................................................................................................................................6 -Opoly..............................................................................................................................................8 Summary..........................................................................................................................................9 -

E.XTENSIONS of REMARKS ISRAEL TODAY Dechai Gur, Has Also Said There Would Be Ber 113,378

9206 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April 15, 1969 E.XTENSIONS OF REMARKS ISRAEL TODAY dechai Gur, has also said there would be ber 113,378. There are 39,305 registered chil fewer acts of terrorism if the standard of dren not on the UNRWA ration list because llving was raised. Israel should invest more of lack of funds. Somehow, they get fed, HON. GEORGE E. BROWN, JR. in industry and vocational tra1n1ng, he said. though, Mr. Geaney told us. When a refu At the Gaza UNRWA Headquarters, Mr. gee becomes a wage earner of 1120 llras per OF CALIFORNIA Geaney the Director had gone to trouble month, his ration is cut. Were the rolls in IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES shoot at the vocational training center where fiated, we asked. That has been greatly ex Monday, April 14, 1969 the students were out of classes and "demon aggerated, he said. strating in sympathy to the political situa There is no vocational training for girls, Mr. BROWN of California. Mr. Speak tion," a phrase used by most Palestinians but there are two six-month sewing courses er, I have been calling the attention of we talked to about the strikes. Mr. Filfil, a a year that women can take, and embroidery my colleagues to a series of articles writ translator at UNRWA, drove us over to see ls encouraged. UNRWA provides for up to ten by Miss Carol Stevens Kovner, writ the center, which was what we had come for. the 9th grade in separate girls and boys ten in Israel and giving a vivid firsthand Mr.