Addiction and Celebritization: Reality Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Assigned to 2Nd Battalion, 3Rd Marine Regiment's Scout Sniper Platoon Focuses in on a Target at Range 400, Twentynine Palms, Admiral William J

Hawaii ARINEARINE MVMOLUME 36, NUMBER 27 2005 THOMAS JEFFERSON AWARD WINNING METRO FORMAT NEWSPAPER JULY 14, 2006 RIMPAC Metal Body Search A-3 B-1 C-1 Word of thanks Lance Cpl. Luke Blom Tony Blazejack A Marine assigned to 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment's Scout Sniper Platoon focuses in on a target at Range 400, Twentynine Palms, Admiral William J. Fallon, commander, United States Pacific Calif. Marines assigned to Hawaii-based 2/3 are in California where they are undergoing training for their upcoming deployment to Iraq. Command, addresses Marines from 1st Battalion, 3rd Regiment at the Base Chapel July 7. Adm. Fallon was aboard base to thank 1/3 "Lava Dogs" for their recent efforts in Afghanistan and to further coordinate with the unit's leaders. Snipers: Eye in the sky 3/3 keeps Iraq’s Lance Cpl. Luke Blom “Everyone thinks our job is just company-level assault range here, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment shooting, but I would say that close July 8. to 90 percent of our job is done Range 400 is an assault course waterways safe MARINE CORPS AIR GROUND without pulling the trigger,” said where Marines clear simulated COMBAT CENTER TWENTYNINE Cpl. Benjamin Pratt, Scout Sniper enemy positions from more than two Sgt. Roe F. Seigle PALMS, Calif. — The Marine scout Platoon, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine kilometers of desert terrain. While 1st Marine Division sniper is known to be a marksman Regiment team leader. “Most of the the rifle platoons rush the objec- who moves through a battlefield like time we’re doing surveillance, recon- tives, they’re given supporting fire HADITHA, Iraq — In Iraq, a country where temper- a ghost, taking shots from impossi- naissance, controlling indirect fire by 81mm mortars, 60mm mortars, atures often soar above 110 degrees and terrain is most- ble distances and hitting his mark or CAS (Close Air Support).” and a squad of heavy machine guns, ly fine grains of sand, Cpl. -

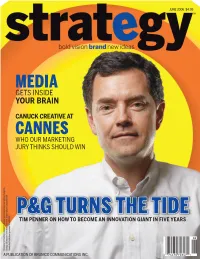

P&G Turns the Tide

MEDIA GETS INSIDE YOUR BRAIN CANUCK CREATIVE AT CANNES WHO OUR MARKETING JURY THINKS SHOULD WIN PP&G&G TTURNSURNS TTHEHE TTIDEIDE TIM PENNER ON HOW TO BECOME AN INNOVATION GIANT IN FIVE YEARS CCover.Jun06.inddover.Jun06.indd 1 55/18/06/18/06 112:13:102:13:10 PPMM SST.6637.TaylorGeorge.dps.inddT.6637.TaylorGeorge.dps.indd 2 55/18/06/18/06 44:23:10:23:10 PMPM taylor george SERVICES OFFERED: Taylor George began operations in the fall of 1995 as a General Agency/AOR two-person design studio. Over the next several years the company grew to a full service agency with a staff of Direct Agency 20. In 2003, Taylor George co founded BRAVE Strategy, Interactive Agency a creative and strategic boutique with expertise in tar- Public Relations Agency geting Canada's diverse Aboriginal population. Design Agency Taylor George and BRAVE are headquartered in Winnipeg, Media Agency Manitoba. The agencies have a sales office in Toronto and will be opening a Vancouver office in July of 2006. “Our approach is all about stories. Stories affect people. APTN Program Guide. Recent national campaigns for Stories APTN have substantially increased audience numbers create emotion. Stories get a response.” Peter George TelPay B-to-B magazine campaign. TelPay President has achieved significant growth since being rebranded by TG in 2005. Subscription Brochure, Manitoba Opera. Season campaign for Manitoba Opera increased subscriptions 28% over the previous year. CLIENT LIST KEY PERSONNEL CONTACT US. 1. Aboriginal People's 12. TelPay Peter George, President and CEO, Taylor George/BRAVE Strategy Television Network 13. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences and the Community at Large

may 2012 NOBODY LOVES YOU A World Premiere Musical Comedy Welcome to The Old Globe began its journey with Itamar Moses and Gaby Alter’s Nobody Loves You in 2010, and we are thrilled to officially launch the piece here in its world premiere production. The Globe has a longstanding relationship with Itamar Moses. He was a Globe Playwright-in-Residence in 2007-2008 when we produced the world premieres of his plays Back Back Back and The Four of Us. Nobody Loves You is filled with the same HENRY DIROCCO HENRY whip-smart humor and insight that mark Itamar’s other works, here united with Gaby’s vibrant music and lyrics. Together they have created a piece that portrays, with a tremendous amount of humor and heart, the quest for love in a world in which romance is often commercialized. Just across Copley Plaza, the Globe is presenting another musical, the acclaimed The Scottsboro Boys, by musical theatre legends John Kander and Fred Ebb. We hope to see you back this summer for our 2012 Summer Shakespeare Festival. Under Shakespeare Festival Artistic Director Adrian Noble, this outdoor favorite features Richard III, As You Like It and Inherit the Wind in the Lowell Davies Festival Theatre. The summer season will also feature Michael Kramer’s Divine Rivalry as well as Yasmina Reza’s Tony Award-winning comedy God of Carnage. As always, we thank you for your support as we continue our mission to bring San Diego audiences the very best theatre, both classical and contemporary. Michael G. Murphy Managing Director Mission Statement The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: Creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; Producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; Ensuring diversity and balance in programming; Providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences and the community at large. -

06 2-3-09 TV Guide.Indd 1 2/3/09 7:50:44 AM

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, February 3, 2009 Monday Evening February 9, 2009 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelor True Beauty Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , FEBRUARY 6 THROUGH THURSDAY , FEBRUARY 12 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Worst CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Chuck Heroes Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX House 24 Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Saturday Night Fever Thelma & Louise ANIM It's Me or the Dog Dogs 101 Animal Cops It's Me or the Dog Dogs 101 CNN Brown-No Bias Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Destroyed Destroyed 1 Way Out 1 Way Out Man vs. Wild How-Made How-Made Destroyed Destroyed DISN Twitches As the Be Wizards Life With Sonny Sonny So Raven Cory E! True Hollywood Story Girls Girls Fashion Police E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter NFL Live Final ESPN2 Women's College Basketball E:60 Challenge NASCAR FAM Secret-Teen Kyle XY Secret-Teen The 700 Club Secret-Teen FX Walk the Line Body Shots HGTV Property Genevieve House My First House Buy Me HGTV Showdown Property Genevieve HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Ancient Discoveries Modern Marvels LIFE Rita Rock Reba Wife Swap DietTribe Will Will Frasier Frasier Listings: MTV Daddy Daddy Hedsor Hall The City Daddy The City Daddy Hedsor Hall NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

President's Message

July/Aug 2021 Vol 56-4 63 Years of Dedicated Service to L.A. Your Pension and Health Care Watchdog County Retirees www.relac.org • e-mail: [email protected] • (800) 537-3522 RELAC Joins National Group to Lobby President’s Against Unfair Social Security Reductions Message RELAC has joined the national Alliance for Public Retirees by Brian Berger to support passage of H.R. 2337, proposed legislation to reform the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) of the Social The recovery appears to be on a real path Security Act. to becoming a chapter of our history with whatever sadness or tragedy of which The Alliance for Public Retirees was created nearly a decade we might each have witnessed or been ago by the Retired State, County and Municipal Employees a part. The next few months will be critical as we continue to Association of Massachusetts (Mass Retirees) and the Texas see a further lessening or elimination of restrictions. I don't Retired Teachers Association to resolve the issues of WEP know how I'll ever be able to leave the house or see friends and the Government Pension Offset (GPO). without a mask, at least in the car or in my pocket. In all this Together with retiree organizations, public employee unions past period, however, work has not lessened at RELAC and the and civic associations across the country, the organization programs have continued with positive gains. For that I thank has worked to advance federal legislation through Congress the support staff, each Board member, and the many of you aimed at reforming both the WEP and GPO laws. -

He's Got the Flavor and the Fav(Or)

small fleet business [ PROFILE He’s Got the Flavor and ] the Fav(or) “Big Rick” heads up a Las Vegas limousine company that has served celebrities, weekend partygoers, and a rapper star from a hit reality VH1 series By Conor Izzett hen your nickname is ance as driver and sidekick to rapper Big Rick, you tend to Flavor Flav on VH1’s hit reality show, get noticed. But Rick B. “Flavor of Love.” Opportunity fi rst Head, standing 6 feet, 9 knocked when the production compa- Winches tall, never expected the kind of ny working for VH1 was looking for a attention he gets now. His wife, Ursula driver for Flav’s original show, “Strange Head, explains. Love,” co-starring former supermodel “We were staying at the Four Sea- Brigitte Nielsen. ■ Big Rick got lots of attention for sons, and these ladies had all their “They wanted a driver who knew his role as chauffeur sidekick to rap- bags, and they all dropped them and Vegas, someone who was not camera per Flavor Fav on VH1. His experi- ence working with celebrities and said, ‘Oh my god, are you Big Rick?’ shy, and was comfortable around ce- partygoers led to steady corporate And he said yes. So then these ladies lebrities,” Big Rick says. “They needed work. start digging though their luggage right someone to do their job and not be in- there in front of the hotel, looking for timidated by the camera. I said, ‘What ‘you’re‘you’re one bigbig mother—’ And the rest their cameras. It was just funny.” camera?’” is history.” Big Rick, owner of Head Limo in Las After that, the audition was simple. -

Reality TV and Interpersonal Relationship Perceptions

REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS ___________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of MissouriColumbia ______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________________ by KRISTIN L. CHERRY Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2008 © Copyright by Kristin Cherry 2008 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS presented by Kristin L. Cherry, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Michael Porter Professor Jon Hess Professor Mary Jeanette Smythe Professor Joan Hermsen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge all of my committee members for their helpful suggestions and comments. First, I would like to thank Jennifer Stevens Aubrey for her direction on this dissertation. She spent many hours providing comments on earlier drafts of this research. She always made time for me, and spent countless hours with me in her office discussing my project. I would also like to thank Michael Porter, Jon Hess, Joan Hermsen, and MJ Smythe. These committee members were very encouraging and helpful along the process. I would especially like to thank them for their helpful suggestions during defense meetings. Also, a special thanks to my fiancé Brad for his understanding and support. Finally, I would like to thank my parents who have been very supportive every step of the way. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………..ii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………..…….…iv LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………….……v ABSTRACT………………………………………………………….…………………vii Chapter 1. -

Newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 212 - September 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/07 (Nr. 212) September 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, schen und japanischen DVDs Aus- Nach den in diesem Jahr bereits liebe Filmfreunde! schau halten, dann dürfen Sie sich absolvierten Filmfestivals Es gibt Tage, da wünscht man sich, schon auf die Ausgaben 213 und ”Widescreen Weekend” (Bradford), mit mindestens fünf Armen und 214 freuen. Diese werden wir so ”Bollywood and Beyond” (Stutt- mehr als nur zwei Hirnhälften ge- bald wie möglich publizieren. Lei- gart) und ”Fantasy Filmfest” (Stutt- boren zu sein. Denn das würde die der erfordert das Einpflegen neuer gart) steht am ersten Oktober- tägliche Arbeit sicherlich wesent- Titel in unsere Datenbank gerade wochenende das vierte Highlight lich einfacher machen. Als enthu- bei deutschen DVDs sehr viel mehr am Festivalhimmel an. Nunmehr siastischer Filmfanatiker vermutet Zeit als bei Übersee-Releases. Und bereits zum dritten Mal lädt die man natürlich schon lange, dass Sie können sich kaum vorstellen, Schauburg in Karlsruhe zum irgendwo auf der Welt in einem was sich seit Beginn unserer Som- ”Todd-AO Filmfestival” in die ba- kleinen, total unauffälligen Labor merpause alles angesammelt hat! dische Hauptstadt ein. Das diesjäh- inmitten einer Wüstenlandschaft Man merkt deutlich, dass wir uns rige Programm wurde gerade eben bereits mit genmanipulierten Men- bereits auf das Herbst- und Winter- offiziell verkündet und das wollen schen experimentiert wird, die ge- geschäft zubewegen. -

Rapper-Repped Clothing Co. Hits Under Armour with TM Suit - Law360 Page 1 of 2

Rapper-Repped Clothing Co. Hits Under Armour With TM Suit - Law360 Page 1 of 2 Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Rapper-Repped Clothing Co. Hits Under Armour With TM Suit By Aaron Vehling Law360, New York (March 06, 2015, 2:07 PM ET) -- Hydro Clothing, an apparel brand featured on several VH1 reality shows featuring former Public Enemy rapper Flavor Flav, on Thursday sued Under Armour Inc. in a California federal court, alleging that Under Armour’s similarly named products infringe on Hydro’s trademarks. Hydro Clothing, a name under which Cohen International Inc., does business, says in its suit that Under Armour’s line of shirts, board shorts, pants, hoodies and other apparel under the name “Hydro” and “Hydro Armour” is deceptive and likely to confuse consumers. The complaint also names Dick’s Sporting Goods Inc., which sells Under Armour’s clothing line. “[Under Armour]’s unauthorized use of the Hydro mark is a trademark use which is likely to confuse the reasonably prudent consumer into believing that [Under Armour]’s infringing apparel products are produced by Cohen,” the complaint says. “On information and belief, Dick’s and [other] retailers are continuing to sell [Under Armour] products bearing the Hydro mark, despite being requested in writing by Cohen to cease their infringement of the Hydro mark.” Before filing the lawsuit, Hydro Clothing also sent Under Armour directly a cease-and- desist notice, but the apparel company continues to promote and sell products under the Hydro mark, the complaint says. -

Faith in Trump, Moral Foundations

SRDXXX10.1177/2378023120956815SociusGraham et al. 956815research-article2020 Original Article Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World Volume 6: 1 –23 © The Author(s) 2020 Faith in Trump, Moral Foundations, and Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions Social Distancing Defiance during the DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120956815 10.1177/2378023120956815 Coronavirus Pandemic srd.sagepub.com Amanda Graham1 , Francis T. Cullen2, Justin T. Pickett3 , Cheryl Lero Jonson4, Murat Haner5, and Melissa M. Sloan5 Abstract Purpose: Over the past several months, the coronavirus has infected more than six million Americans and killed nearly 200,000. Governors have issued stay-at-home orders, and prosecutors have filed criminal charges against individuals for defying those orders. And yet many Americans have still refused to keep their distance from their fellow citizens, even if they had symptoms of infection. The authors explore the underlying causes for those who intend to defy these norms. Methods: Using national-level data from a March 2020 survey of 989 Americans, the authors explore intentions to defy social distancing norms by testing an interactionist theory of foundation-based moral behavior in combination with faith in President Trump during the coronavirus pandemic. The analysis controls for a range of variables, including measures of low self-control and deterrence. Results: Low self-control is the strongest predictor of defiance intentions. Consistent with interactionist theory, defiance intentions are significantly higher for those holding specific faith in Trump and those endorsing binding foundations. Furthermore, the interaction of these two variables is significant and in the predicted direction. The results hold for two different measures of faith in Trump. -

College Admissions, Rigged for the Rich

$2.75 DESIGNATED AREASHIGHER©2019 WSCE D WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13,2019 latimes.com College admissions, riggedfor therich Scheme paid coaches, faked test scores to securespots forchildren of the wealthy By Joel Rubin, Hannah Fry, Richard Winton and MatthewOrmseth When it came to getting their daughtersintocollege, actress Lori Loughlinand fashion designer J. Mossimo Giannulli were taking no chances. The wealthy,glamorous couple were determined their girls would attend USC, ahighly competitive school that offers seats only CJ Gunther EPA/Shutterstock to afractionofthe thou- WILLIAM SINGER sands of students who apply pleaded guiltyTuesdayto eachyear. racketeering and other So they turned to William charges in the scheme. Singer and the “side door” the NewportBeach busi- nessman said he had built intoUSC and otherhighly The big sought afteruniversities. Half amillion dollars later — Allen J. Schaben Los Angeles Times $400,000ofitsent to Singer FOR MILLIONS OF CALIFORNIANS who live near thecoast, the threatofrising sea levels and storms is and $100,000 to an adminis- business very real. Last year,winter stormseroded Capistrano Beach in Dana Point, causing aboardwalk to collapse. trator in USC’s vaunted ath- leticprogram —the girls were enrolled at the school. of getting Despitehaving nevercom- peted in crew,both had been ‘Massive’damagemay givencoveted slots reserved NEWSOM for rowers who were ex- accepted pected to join the school’s team. “This is wonderful news!” Experts call for TO HALT be the norm by 2100 Loughlin emailed Singer af- terreceiving word that a reforms to levelthe spotfor her second daughter playing field in a DEATH had been secured. She add- thriving industrythat Rising seas and routine storms couldbemore ed ahigh-five emoji.