Discussion Paper: Evaluating Management Effectiveness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUNE 2018 Editor: CONTENTS Ian Urquhart JUNE 2018 • VOL

JUNE 2018 Editor: CONTENTS Ian Urquhart JUNE 2018 • VOL. 26, NO. 2 Graphic Design: Keystroke Design & Production Inc. Doug Wournell B Des, ANSCAD Features Association News www.keystrokedesign.com Printing by: 4 A Wilderness Adventure with 28 The 2018 Climb for Wilderness Topline Printing Inc. My Grandkids www.toplineprinting.ca 30 Introducing AWA’s Two New 8 The Hungry Bend Sandhills Conservation Specialists Printed on FSC Certified Paper 11 Linking Nature and Persons with 32 Moments That Matter: a Disability: Introducing Coyote Wendy Ryan’s life of defending Lake Lodge the Castle Wilderness 14 Trails, Sediment, and Aquatic Habitat: McLean Creek Wilderness Watch 16 Protecting & Recovering Wildlife in Canada 34 Updates 19 Comparing Mining Liability 36 Annual General Meeting Programs: Lessons for Alberta? ALBERTA WILDERNESS 21 The Public Lands Trifecta: ASSOCIATION Department Important Progress Made “Defending Wild Alberta through Where the Wild Things Are: Awareness and Action” 24 Reader’s Corner harnessing the power of citizen 37 Alberta Wilderness Association is scientists a charitable non-government In Memoriam: Charlie Russell, 39 organization dedicated to the Louise Guy Poetry Corner August 19, 1941 – May 7, 2018 26 completion of a protected areas donation, call 403-283-2025 or contribute online at AlbertaWilderness.ca. Wild Lands Advocate is published four times a year, by Alberta Wilderness Association. The opinions expressed Cover Photos by the authors in this publication are Cotton grass (Eriophorum species), not necessarily those of AWA. The featured prominently in this Vivian editor reserves the right to edit, reject or Pharis photo, is a common and co- withdraw articles and letters submitted. -

Spiders of Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park

Spiders of Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park Xysticus obscures. Crab spider, Robert G. Holmberg Centre for Science, Athabasca University, Athabasca, Alberta, T9S 3A3 E-mail: [email protected] and Donald J. Buckle 620 Albert Avenue, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 1G7 E-mail: [email protected] Prepared for the Parks and Protected Areas Division Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation Edmonton, Alberta, Canada December 2008 Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Study Area .......................................................................................................................... 4 Methods............................................................................................................................. 10 Results ............................................................................................................................... 14 Species Collected .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park ............................................................. 26 Numbers of Species and Number of Specimens ....................................................... 26 Spiders Collected in Large Numbers ....................................................................... -

Download the 2018-2019 Annual Report

Alberta Wilderness Association Annual Report 2018 - 2019 1 2 Wilderness for Tomorrow AWA's mission to Defend Wild Alberta through Awareness and Action by inspiring communities to care is as vital, relevant and necessary as it ever was. AWA is dedicated to protecting our wild spaces and helping create a world where wild places, wildlife and our environment don't need protecting. As members and supporters, you inspire the AWA team; your support in spirit, in person and with your financial gifts makes a difference. We trust you will be inspired by the stories told in this 2018 – 2019 annual report. Contributions to the Annual Report are provided by AWA board and staff members with thanks to Carolyn Campbell, Joanna Skrajny, Grace Wark, Nissa Petterson, Ian Urquhart, Owen McGoldrick, Vivian Pharis, Cliff Wallis, Chris Saunders and Sean Nichols. - Christyann Olson, Executive Director Alberta Wilderness Association Provincial Office – AWA Cottage School 455 – 12 St NW, Calgary, Alberta T2N 1Y9 Phone 403.283.2025 • Fax 403.270.2743 Email: [email protected] Web server: AlbertaWilderness.ca Golden Eye Mother and Chicks on the Cardinal River and Mountain Bluebird at her nest © C. Olson 3 Contents Wilderness for Tomorrow .............................................. 2 Contents ......................................................................... 3 A Successful Year ............................................................ 6 Board and Staff ............................................................... 7 Board of Directors ......................................................... -

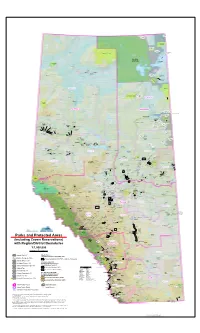

Alberta Parks and Protected Areas

126 Andrew Lake 126 Future PRA (HRS) 126 Slave River Rapids Future PRA (HRS) 125 125 125 124 124 124 123 123 123 122 Colin-Cornwall 122 Lakes Wildland 122 121 121 121 120 La Butte Creek 120 Wildland 120 119 119 Kazan 119 Future Wildland 118 (HRS) Hot Pot NA (PNT) Fidler-Greywillow 118 Wildland Caribou Mountains Wildland 118 117 117 117 116 Egg Island 116 Ecological 116 Reserve 115 115 Wood Buffalo 115 National Park 114 114 (Alberta Portion) Fidler-Greywillow 114 Wildland 113 Hay-Zama Lakes 113 Wildland 113 112 112 Watt Mountain NA (PNT) 112 111 111 111 110 110 Ponton River 110 109 NA (PNT) 109 Ponton River Caribou River NA (PNT) South NA (PNT) Caribou River NA 109 108 Boyer NA (PNT) Child Lake Meadows NA Fort Vermilion PRA 108 Richardson 107 Rainbow Lake PRA 108 Future Wildland (HRS) Maybelle River 107 Machesis Lake PRA Wildland 107 106 106 R ic 105 Harper Creek NA 106 D h u a Athabasca Dunes n rd e s s o Ecological Res. 105 W n il R 105 d iv 104 la e n r d 104 104 103 103 Buffalo Tower PRA 103 102 102 101 102 Marguerite River 101 Peace River Wildland 13 12 101 5 100 11 10 9 4 3 2 8 7 7 6 6 5 4 3 10 9 8 2 100 25 24 14 13 12 11 23 22 21 20 19 19 18 17 16 15 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 100 25 24 23 22 21 20 99 99 99 98 Burning Sulphur NA (PNT) 98 Birch Mountains 98 Birch Mountains Wildland Future Expansion 97 Twin Lakes PRA (HRS) 97 Fort McMurray 97 96 96 96 95 Notikewin 95 Prov. -

The Alberta GPI Accounts: Parks and Wilderness

The Alberta GPI Accounts: Parks and Wilderness Report # 21 by Mary Griffiths Sara Wilson Mark Anielski September 2001 The Alberta GPI Accounts: Parks and Wilderness About the Pembina Institute The Pembina Institute is an independent, citizen-based organization involved in environmental education, research, public policy development and corporate environmental management services. Its mandate is to research, develop, and promote policies and programs that lead to environmental protection, resource conservation, and environmentally sound and sustainable resource management. Incorporated in 1985, the Institute’s main office is in Drayton Valley, Alberta with additional offices in Calgary and Ottawa, and research associates in Edmonton, Toronto, Saskatoon, Vancouver and other locations across Canada. The Institute’s mission is to implement holistic and practical solutions for a sustainable world. The Green Economics Program is dedicated to designing and implementing practical, street-smart economic tools that would reorient society back to the original meaning of the word “economy”—the care and management of the wealth of the household. By developing new tools for measuring the true wealth or well-being of nations, we can help guide Canadians and Albertans to a sustainable future. For more information on the Pembina Institute’s work, please visit our website at www.pembina.org, or contact: The Pembina Institute Box 7558 Drayton Valley, AB T7A 1S7 tel: 780-542-6272 fax: 780-542-6464 e-mail: [email protected] About this Report This is one of 28 reports that provide the background for the Genuine Progress Indicators (GPI) System of Sustainable Well-being Accounts. It explains how we derived the index that was earlier published in “Sustainability Trends 2000: The Genuine Progress Statement for Alberta, 1961 to 1999.” The research for this report was completed near the end of 2000. -

Community Development Communications 740, 10405 Jasper Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4R7

3494 Com Dev Cover 9/9/05 1:16 PM Page 1 ANNUAL REPORT COMMUNITYboovbm!sfqpsu BMCFSUB!DPNNVOJUZ! DEVELOPMENT EFWFMPQNFOU FOR THEgps!uif!gjtdbm!zfbs!foefe!Nbsdi!42-!3116 FISCAL YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 2005 3494 Com Dev Cover 9/9/05 1:16 PM Page 2 Note to Readers: Copies of the annual report are available on the website or by contacting: Alberta Community Development Communications 740, 10405 Jasper Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4R7 Phone: (780) 427-6530 Fax: (780) 427-1496 Website: www.cd.gov.ab.ca ISBN: 0-7785-2238-5 Table of Contents Preface ii Minister’s Accountability Statement iii Message from the Minister 1 Management’s Responsibility for Reporting 2 Overview Ministry Entities 3 Operational Overview 7 Performance Highlights 9 Financial Highlights 12 Results Analysis Message from the Deputy Minister 17 Report of the Auditor General on the Results of Applying Specified Auditing Procedures to Key Performance Measures 19 Core Businesses, Goals, Strategies and Performance Measures 20 1. Support individuals and organizations through 20 community development 2. Protect human rights, promote fairness and access, and support 29 the protection, inclusion, and participation of all Albertans 3. Preserve, protect and present Alberta's history, culture, 33 provincial parks and protected areas Cross-Ministry Priority Policy Initiatives 44 Integrated Results Analysis 47 Forward Looking Information 50 Financial Information Index of Financial Statements 51 Other Information Statement of Write-Offs 213 Acts Administered by Community Development 214 Performance Measures’ Results at a Glance 216 Performance Measures’ Data Sources and Methodology 217 Alphabetical List of Government Entities’ Financial Statements 220 Government Organization Changes, 2004-05 223 Readership Survey 225 Alberta Community Development 2004 – 05 ANNUAL REPORT i Preface Public Accounts, 2004-05 The Public Accounts of Alberta are prepared in accordance with the Financial Administration Act and the Government Accountability Act. -

Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Eaglenest Portage Site

Advancing Boreal Forest Archaeology: Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Eaglenest Portage Site A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Matthew Rawluk © Copyright, Matthew Rawluk, March 2019. All Rights Reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying, publication, or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology 55 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B1 OR Dean College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5C9 Canada i ABSTRACT This thesis presents the results of an intrasite spatial analysis study of an archaeological assemblage from the Eaglenest Portage site in the Birch Mountains of northern Alberta. -

PROGRESS REPORT a Review of Our Progress in 2015

Land-use Framework Regional Plans PROGRESS REPORT a review of our progress in 2015 LUF For more information about Land-use Framework (LUF) Regional Plans Progress Report: A Review of Our Progress in 2015 contact: Land Use Secretariat: 6th Floor, Forestry Building 9920 – 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2M4 Phone: 780.644.7972 Email: [email protected] Visit the Alberta Land-use website at landuse.alberta.ca to download a copy of this report. ISBN: ISBN 978-1-4601-3494-8 (print) ISBN 978-1-4601-3495-5 (online) Printed: November 2017 ProgressReport 2015 Introduction The Land-use Framework (LUF) introduced in 2008 provides a blueprint for land-use management and decision-making to address mounting pressures on Alberta’s land and resources. It also establishes a vision of Albertans working together to respect and care for the land as a foundation for our environmental, economic and social well-being. Since that time, many advances have been made including the establishment of the Alberta Land Stewardship Act (2011) and the adoption of an integrated and coordinated approach to resource management. This approach encourages cumulative effects management of natural assets taking into account the growing impacts of development on the land over several years. It relies on legislation, regulations and on LUF regional plans developed for each of seven regions within the province, to provide direction. To date, two regional plans – the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan (2012) for northeastern Alberta and the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan (2014) for southern Alberta – have become regulations. Regional plans are developed with input and feedback from Albertans. -

Natural Regions & Subregions of Alberta

Natural Regions & Subregions of Alberta A Framework for Alberta’s Parks Natural Regions & Subregions of Alberta A Framework for designate and secure land that will represent the variety of these landscapes within the province. Alberta’s Parks By acting now to identify and protect these areas, we can help to ensure that Alberta’s natural Alberta enjoys a wealth of natural features that diversity will continue to exist for the benefit of can be seen in the diversity of our landscapes. future generations. They vary from hot, dry badlands to vast, unbroken forests, to alpine tundra and massive This report provides an overview of the land ice fields. Within the Boreal Forest, Grassland, classification system that we use to describe Rocky Mountains, Canadian Shield, Parkland our natural landscapes and that also serves as and Foothills natural regions, protected areas a tool to help us measure our progress towards have been set aside to conserve examples of this completing a network of protected areas. natural diversity. Today and into the future, our challenge is not only to maintain the integrity Spectacular Kakwa of these protected areas but also to continue to Wildland Provincial Park 2 Natural Regions: A reduced variety of features. The largest units, the natural regions, are divided into subregions, Top-Down Classification which in turn encompass a series of natural history themes. These themes are further broken Land classification for protected areas is based down into a number of more specific categories. on natural or biogeographic features such as geology, landform, soils and hydrology. Other factors affecting classification include an area’s climate, vegetation and wildlife (see Fig. -

2016/17 Alberta Parks Capital Programs

2016/17 Alberta Parks Capital Programs Capital Maintenance and Renewal (CMR) Major Projects Region Park Description Central Blackfoot/Cooking Lake Trail System Upgrade Provincial Recreation Area Central Jarvis Bay Provincial Park Park Upgrade Central Miquelon Lake Provincial Lift station upgrade Park Central Miquelon Lake Provincial Staff Residence Park Central Miquelon Lake Provincial Water Plant Upgrade Park Central Miquelon Provincial Park Sewer Main Upgrade Central Pigeon Lake Provincial Park Water Tower Refurbishment Central Strathcona Science Provincial Park Upgrade Park Central Wabamun Lake Provincial Parking lots Expansion Park Kananaskis Kananaskis Region Program to upgrade campgrounds and day-use areas throughout Kananaskis Kananaskis Kananaskis Region Program to upgrade or replace vault toilets throughout Kananaskis Kananaskis Kananaskis Region Program to upgrade water and wastewater systems throughout Kananaskis Kananaskis Kananaskis Region Regional fuel systems upgrades Kananaskis Peter Lougheed Provincial Design work to replace cabins C & D at William Watson Lodge in 2017/18 Park Northeast Sr. Winston Churchill SWC Water-Sewer Upgrade Provincial Park Northwest Lesser Slave Lake Provincial BCBC power upgrade Park Northwest Lesser Slave Lake Provincial Boreal centre for Bird Conservation Project implementation beginning in 2016/17 in beginning implementation Project Park Northwest Lesser Slave Lake Provincial Devonshire Beach parking conversion Park Northwest Northwest Region Regional Outhouse Replacement/Upgrades Northwest -

History of the Archaeological Society in Lethbridge

Archaeolo No. 42 ISSN 0701-1176 Spring 2005 ilfllilllf WMMSvmmMk lii llillllll^lllllll IPS Road cut ihrcuMU vVsf»cv Point Wmm lor Moiirrt ysth«rs&! starts •••' ''•••:v,:--r:::~y« IIIPI yll Abraham Lake 111 Illil lllllli 111!! ^iliiiiiiliiliil Hill ilil Contents 2 Provincial Society Officers 2004- Features 2005 5 Alberta Fieldwork News 2004 10 SCAPE Report of Activities 2004 News & Short Reports 15 Searching for David Thompson 3 Editor's Note 20 Alberta Archaeological Review 3 In Memory Index: Issues 1-41 4 Scanning the Literature 30 A History of the Archaeological Society in Lethbridge ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF ALBERTA Charter #2805, registered under the Societies Act of Alberta on February 7, 1957 PROVINCIAL SOCIETY OFFICERS 2004-2005 RED DEER CENTRE: President: Karen Kehoe President Dr. Shawn Bubel 3706-43 Avenue Department of Geography Red Deer AB T2N 3B6 University of Lethbridge Phone: 403-358-2391 Lethbridge AB T1K3M4 [email protected] Phone: 403-329-2531 Provincial Rep: Jean Kaufmann [email protected] SOUTHEASTERN ALBERTA Past-President Kate R. Chapman ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY: R.R.#2, Lacombe AB President: Janice Andreas T4L 2N2 46 Rossland Crescent SE Phone: 403-885-2924 Medicine Hat AB T1B 2B6 k_r_chapman @ hotmail.com Phone: 403-526-3346 Provincial Rep: Ray Lusty Executive/ Jim McMurchy Secretary/ 97 Eton Road West STRATHCONA CENTRE; Treasurer Phone:403-381-2655 President: George Chalut [email protected] 14716-65 Street Edmonton AB T5A 2E1 Alberta Dr. John Dormaar Phone:780-431-2329 Archaeological Research Centre Email: Review: -

Survey of the Odonate Fauna in Willmore Wilderness Park

Survey of the Odonate Fauna in Willmore Wilderness Park Prepared by Doug Macaulay, P. Biol. (Alberta Lepidopterists’ Guild) March 4, 2008 Prepared for Parks Resource Management Coordination Branch Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 1 RESULTS ................................................................................................... 1 SPECIES NOTES ...................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................... 5 REFERENCES........................................................................................... 6 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Habitats and locations of collection sites in Willmore Wilderness Park....................................................................... 1 Table 2. Odonate species confirmed for Willmore Wilderness Park, western portion........................................................................ 3 Table 3. Other odonate species predicted to occur within Willmore Wilderness Park....................................................................... 3 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Collection sites in the western part of Willmore Wilderness Park.......................................................................................... 2 APPENDICES Appendix 1. List of species found in Willmore Wilderness Park .......... 8 Appendix 2. Complete data for specimens collected in