Artmaking from Mexico to China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery of Mexican Art

V oices ofMerico /January • March, 1995 41 Gallery of Mexican Art n the early the 1930s, Carolina and Inés Amor decided to give Mexico City an indispensable tool for promoting the fine arts in whatI was, at that time, an unusual way. They created a space where artists not only showed their art, but could also sell directly to people who liked their work. It was a place which gave Mexico City a modem, cosmopolitan air, offering domestic and international collectors the work of Mexico's artistic vanguard. The Gallery of Mexican Art was founded in 1935 by Carolina Amor, who worked for the publicity department at the Palace of Fine Arts before opening the gallery. That job had allowed her to form close ties with the artists of the day and to learn about their needs. In an interview, "Carito" —as she was called by her friends— recalled a statement by the then director of the Palace of Fine Arts, dismissing young artists who did not follow prevailing trends: "Experimental theater is a diversion for a small minority, chamber music a product of the court and easel painting a decoration for the salons of the rich." At that point Carolina felt her work in that institution had come to an end, and she decided to resign. She decided to open a gallery, based on a broader vision, in the basement of her own house, which her father had used as his studio. At that time, the concept of the gallery per se did not exist. The only thing approaching it was Alberto Misrachi's bookstore, which had an The gallery has a beautiful patio. -

David Alfaro Siqueiros's Pivotal Endeavor

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-15-2016 David Alfaro Siqueiros’s Pivotal Endeavor: Realizing the “Manifiesto de New York” in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop of 1936 Emily Schlemowitz CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/68 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] David Alfaro Siqueiros’s Pivotal Endeavor: Realizing the “Manifiesto de New York” in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop of 1936 By Emily Schlemowitz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Hunter College of the City of New York 2016 Thesis Sponsor: __May 11, 2016______ Lynda Klich Date First Reader __May 11, 2016______ Harper Montgomery Date Second Reader Acknowledgments I wish to thank my advisor Lynda Klich, who has consistently expanded my thinking about this project and about the study of art history in general. This thesis began as a paper for her research methods class, taken my first semester of graduate school, and I am glad to round out my study at Hunter College with her guidance. Although I moved midway through the thesis process, she did not give up, and at every stage has generously offered her time, thoughts, criticisms, and encouragement. My writing and research has benefited immeasurably from the opportunity to work with her; she deserves a special thank you. -

Jazzamoart El Estado Chileno No Es Editor

EXCELSIOR MIÉrcoles 27 DE MAYO DE 2015 Foto: CortesíaFoto: INAH PATRICIA LEDESMA B. TEMPLO MAYOR, NUEVO TIMÓN La arqueóloga Patricia Ledesma Bouchan fue designada ayer como nueva titular del Museo del Templo Mayor, en sustitución de Carlos Javier González. Así lo anunció el Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia mediante un comunicado, en el que destacó su labor en temas relacionados “con la gestión del patrimonio arqueológico y la divulgación del conocimiento científico”. [email protected] @Expresiones_Exc Foto: Cortesía Nuria Gironés El Estado chileno no es editor “Chile tiene que hacerse cargo de un problema estructural que se arrastra desde la dictadura militar (1973-1990), cuando se destruyó el tejido cultural por la censura”, dice en entrevista Marcelo Montecinos, presidente de la Cooperativa de Editores de La Furia. >4 Reaparece Jazzamoart Una obra de carácter vibrante, que a ritmo de pinceladas “se hace lumínica y cromática”, es lo que ofrecerá el pintor y escultor mexicano Francisco Javier Vázquez, mejor conocido como Jazzamoart, Revelan la trama acerca de la sustracción, en 1904, del llamado en su exposición Improntas, que M A PA se presenta a partir de ayer en el Lienzo de Tlapiltepec, patrimonio “extraviado” de México > 5 Museo Dolores Olmedo. >6 Foto: Cortesía Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca FOTOGALERÍA ESPECIAL Exposición Visita MULTI Galería Throckmorton Recintos celebran ¿Qué me pongo? MEDIA Exhiben en Nueva York imágenes Recomendaciones para Marcelino Perelló. 2 poco comunes de Frida Kahlo. la Noche de los Museos. 2: EXPRESIONES MIÉRCOLES 27 DE MAYO DE 2015 : EXCELSIOR ¿Qué me pongo? PALACIO DE CULTURA BANAMEX MARCELINO PERELLÓ El desastre que viene Retorna La jungla sudamericana no es únicamente el pulmón de la Tierra. -

Morton Subastas SA De CV

Morton Subastas SA de CV Lot 1 CARLOS MÉRIDA Lot 3 RUFINO TAMAYO (Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, 1891 - Ciudad de México, 1984) (Oaxaca de Juárez, México, 1899 - Ciudad de México, 1991)< La casa dorada, 1979 Mujer con sandía, 1950 Firmada a lápiz y en plancha Firmada Mixografía 97 / 100 Litografía LIX / LX Procedencia: Galería del Círculo. Publicada en: PEREDA, Juan Carlos, et al. Rufino Tamayo Catalogue Con documento de la Galería AG. Raisonné Gráfica / Prints 1925-1991, Número 32. México. Fundación Olga y "Un hombre brillante que se daba el lujo de jugar integrando todos los Rufino Tamayo, CONACULTA, INBA, Turner, 2004, Pág. 66, catalogada 32. elementos que conocía, siempre con una pauta: su amor a lo indígena que le dio Impresa en Guilde Internationale de l'Amateur de Gravures, París. su razón de ser, a través de una geometría. basado en la mitología, en el Popol 54.6 x 42.5 cm Vuh, el Chilam Balam, los textiles, etc. Trató de escaparse un tiempo (los treintas), pero regresó". Miriam Kaiser. $65,000-75,000 Carlos Mérida tuvo el don de la estilización. Su manera de realizarlo se acuñó en París en los tiempos en que se cocinaban el cubismo y la abstracción. Estuvo cerca de Amadeo Modigliani, el maestro de la estilización sutil, y de las imágenes del paraíso de Gauguin. Al regresar a Guatemala por la primera guerra mundial decide no abandonar el discurso estético adopado en Europa y más bien lo fusiona con el contexto latinoamericano. "Ningún signo de movimiento organizado existía entonces en nuestra América", escribe Mérida acerca del ambiente artístico que imperaba a su llegada a México en 1919. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

Grand Canyon, Zion and Sedona Experience”

1 2 Inverarte Art Gallery presents Jorge Obregon “Grand Canyon, Zion and Sedona Experience” Opening and Artist Reception, Wednesday, October 17th, 2018 On view October 17th, 2018 through January 9th, 2019 Inverarte Art Gallery 923 N Loop 1604 E Ste 103, San Antonio, TX 78232 Contact +1 210-305-6528 mail: [email protected] Mon - Thu 10:00 to 19:00 Fri - Sat 10:00 to 17:00 www.inverarteartgallery.com Grand Canyon, Zion, and Sedona Experience “Grand Canyon, Zion and Sedona Experience,” this could be the title showed not only the landscape, but they also included the buildings and of an adventure movie or a documentary, but in this case, it is the name of people who populated those places. Therefore those paintings were more this exhibition which consists of 18 paintings made by Jorge Obregon in than artworks but also historical testimonies of the landscape and customs his latest expedition. But looking back at it, why not, it is also the name of of that time. However, it was not until 1855, with the arrival to Mexico of the this catalogue that narrates a little of the history of such excellent artist, as Italian painter Eugenio Landesio, as a landscape and perspective professor well as his participation and relationship with the history of art in Mexico. at the Academy of San Carlos, that landscape painting truly began in Mexico. Moreover, it presents us a movie in slow motion, meaning, frame by frame, Eugenio Landesio had several excellent disciples, but the most outstanding about his adventure through the Colorado Plateau. -

Historia De Mujeres Artistas En México Del Siglo Xx

Mónica Castillo, Autorretrato como cualquiera, 1996 – 1997, óleo sobre tela, 80 x 70 cm HISTORIA DE MUJERES ARTISTAS EN MÉXICO DEL SIGLO XX ÍNDICE Presentación 3 Contexto La mujer en la historia 4 Presencia femenina en el arte 5 Ejes temáticos 7 Mujeres artistas en México. (fragmentos) 12 Una constelación de implacables buscadoras Germaine Gómez Haro Punto de Fuga (fragmentos) 16 Pura López Colomé Artistas 20 Glosario 39 Links 40 Departamento de Educación 2 PRESENTACIÓN El reconocimiento de la presencia de mujeres artistas en la historia del arte ha permitido que los contenidos, los modos de interpretación y las categorías de análisis se transformen, se especifiquen, y al mismo tiempo, se expandan: las reflexiones teóricas y prácticas se han diversificado cada vez más, desde los temas y conceptos hasta los medios por los que se expresan los artistas; permitiendo, así, las relecturas y re-significados de las obras. Historia de mujeres es una exposición que reconoce la colaboración de las mujeres artistas mexicanas, quienes aportaron con sus particulares puntos de vista a la historia del arte nacional e internacional. Así, la exposición muestra tres generaciones de creadoras a lo largo del siglo XX: La primera generación son las artistas nacidas a principios del siglo que se distinguieron por un trabajo de gran calidad técnica, como Angelina Beloff, Tina Modotti, Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo, etc. La segunda generación incluye a las que nacieron alrededor de los años 20 y 30, como Lilia Carrillo, Joy Laville, Helen Escobedo, Marta Palau y Ángela Gurría; ellas iniciaron una etapa de experimentación en las nuevas tendencias. -

A Promenade Trough the Visual Arts in Carlos Monsivais Collection

A Promenade Trough the Visual Arts in Carlos Monsivais Collection So many books have been written, all over the world and throughout all ages about collecting, and every time one has access to a collection, all the alarms go off and emotions rise up, a new and different emotion this time. And if one is granted access to it, the pleasure has no comparison: with every work one starts to understand the collector’s interests, their train of thought, their affections and their tastes. When that collector is Carlos Monsiváis, who collected a little bit of everything (that is not right, actually it was a lot of everything), and thanks to work done over the years by the Museo del Estanquillo, we are now very aware of what he was interested in terms of visual art in the 20th Century (specially in painting, illustration, engraving, photography). It is only natural that some of the pieces here —not many— have been seen elsewhere, in other exhibitions, when they were part of the main theme; this time, however, it is a different setting: we are just taking a stroll… cruising around to appreciate their artistic qualities, with no specific theme. This days it is unusual, given that we are so used to looking for an overarching “theme” in every exhibition. It is not the case here. Here we are invited to partake, along with Carlos, in the pleasures of color, texture, styles and artistic schools. We’ll find landscapes, portraits, dance scenes, streetscapes, playful scenes. All executed in the most diverse techniques and styles by the foremost mexican artist of the 20th Century, and some of the 21st as well. -

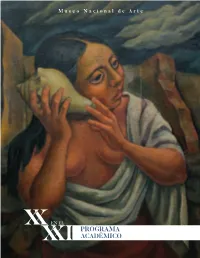

PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Imagen De Portada

Museo Nacional de Arte PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Imagen de portada: Gabriel Fernández Ledesma (1900-1983) El mar 1936 Óleo sobre tela INBAL / Museo Nacional de Arte Acervo constitutivo, 1982 PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Diego Rivera, Roberto Montenegro, Gerardo Murillo, Dr. Atl, Joaquín Clausell, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Lola Cueto, María Izquierdo, Adolfo Best Maugard, Pablo O’Higgins, Francisco Goitia, Jorge González Camarena, Rufino Tamayo, Abraham Ángel, entre muchos otros, serán los portavoces de los grandes cometidos de la plástica nacional: desde los pinceles transgresores de la Revolución Mexicana hasta los neomexicanismos; de las Escuelas al Aire Libre a las normas metódicas de Best Maugard; del dandismo al escenario metafísico; del portentoso género del paisaje al universo del retrato. Una reflexión constante que lleva, sin miramientos, del XX al XXI. Lugar: Museo Nacional de Arte Auditorio Adolfo Best Maugard Horario: Todos los martes de octubre y noviembre De 16:00 a 18:00 h Entrada libre XX en el XXI OCTUBRE 1 de octubre Conversatorio XX en el XXI Ponentes: Estela Duarte, Abraham Villavicencio y David Caliz, curadores de la muestra. Se abordarán los grandes ejes temáticos que definieron la investigación, curaduría y selección de obras para las salas permanentes dedicadas al arte moderno nacional. 8 de octubre Decadentismo al Modernismo nacionalista. Los modos de sentir del realismo social entre los siglos XIX y XX Ponente: Víctor Rodríguez, curador de arte del siglo XIX del MUNAL La ponencia abordará la estética finisecular del XIX, con los puentes artísticos entre Europa y México, que anunciaron la vanguardia en la plástica nacional. 15 de octubre La construcción estética moderna. -

Carlos Mérida 2019

EXPOSICIONES INDIVIDUALES 1910 CARLOS MÉRIDA. Periódico El Economista. Guatemala. Guatemala. 1915 CARLOS MÉRIDA. Edificio Rosenthal. Guatemala, Guatemala. 1919 CARLOS MÉRIDA. El Diario de los Altos. Guatemala. Guatemala. 1920 INTROITO DE CARLOS MÉRIDA. Antigua Academia de Bellas Artes. México, D.F. 1926 CARLOS MÉRIDA. Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes. Guatemala. Guatemala. 1927 AQUARELLES/PEINTURES. Galerie Des Quatre Chemins. París, Francia. 1930 RECENT PAINTINGS AND AQUARELLES BY CARLOS MÉRIDA. Delphic Studios. Nueva York, NY, EUA. 1931 DIEZ ACUARELAS DE CARLOS MÉRIDA. Club de Escritores. México, D.F. 1932 CATORCE ACUARELAS RECIENTES. Galería Posada. México, D.F. 1935 PAINTINGS AND WATERCOLORS BY CARLOS MÉRIDA, CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN PAINTER. Katherine Kuh Gallery. Chicago, IL, EUA. 1936 MÉRIDA NEW OILS. Stendhal and Stanley Rose Galleries. Los Ángeles, CA, EUA. NEW PAINTINGS BY CARLOS MÉRIDA. Stendhal and Stanley Rose Galleries. Los Ángeles, CA, EUA. 1937 CARLOS MÉRIDA. Georgette Passedoit Gallery. Nueva York, NY, EUA. ÓLEOS, ACUARELAS, LITOGRAFÍAS DE CARLOS MÉRIDA. Departamento de Bellas Artes, Secretaría de Educación Pública. México, D.F. 1939 TEN VARIATIONS ON A MAYAN MOTIF. TEN PLASTIC CONCEPTS ON A LOVE THEME. The Katherine Kuh Gallery. Chicago, IL, EUA. TWENTY RECENT PAINTINGS. TEN VARIATIONS ON A MAYAN MOTIF. TEN PLASTIC CONCEPTS ON A LOVE THEME. Georgette Passedoit Gallery. Nueva York, NY, EUA. VEINTE PINTURAS RECIENTES. DIEZ VARIACIONES SOBRE UN ANTIGUO MOTIVO MAYA. DIEZ CONCEPTOS PLÁSTICOS SOBRE UN TEMA DE AMOR. Galería de Arte UNA. México, D.F. 1940 COLORED DRAWINGS, EIGHT VARIATIONS ON A MAYAN MOTIF, AND EIGHT PLASTIC CONCEPTS ON A LOVE THEME. Witte Memorial Museum. San Antonio, TX, EUA. 1942 EL CORRIDO DE LA MUSARAÑA, LA CUCAÑA Y LA CARANTOÑA. -

INFORME ANUAL CORRESPONDIENTE AL ÚLTIMO SEMESTRE DEL 2013 Y PRIMER SEMESTRE DE 2014

INFORME ANUAL CORRESPONDIENTE AL ÚLTIMO SEMESTRE DEL 2013 y PRIMER SEMESTRE DE 2014. Informe presentado por el Consejo Directivo Nacional de la Sociedad Mexicana de Autores de las Artes Plásticas, Sociedad De Gestión Colectiva De Interés Público, correspondiente al segundo semestre del 2013 y lo correspondiente al año 2014 ante la Asamblea General de Socios. Nuestra Sociedad de Gestión ha tenido varios resultados importantes y destacables con ello hemos demostrado que a pesar de las problemáticas presentadas en nuestro país se puede tener una Sociedad de Gestión como la nuestra. Sociedades homologas como Arte Gestión de Ecuador quienes han recurrido al cierre de la misma por situaciones económicas habla de la crisis vivida en nuestros días en Latinoamérica. Casos como Guatemala, Colombia, Honduras en especial Centro América, son a lo referido, donde les son imposibles abrir una representación como Somaap para representar a sus autores plásticos, ante esto damos las gracias a todos quienes han hecho posible la creación y existencia de nuestra Sociedad Autoral y a quienes la han presidido en el pasado enriqueciéndola y dándoles el impulso para que siga existiendo. Es destacable mencionar los logros obtenidos en las diferentes administraciones donde cada una han tenido sus dificultades y sus aciertos, algunas más o menos que otras pero a todas les debemos la razón de que estemos en estos momentos y sobre una estructura solida para afrontar los embates, dando como resultado la seguridad de la permanencia por algunos años más de nuestra querida Somaap. Por ello, es importante seguir trabajando en conjunto para lograr la consolidación de la misma y poder pensar en la Somaap por muchas décadas en nuestro país, como lo ha sido en otras Sociedades de Gestión. -

Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica Opularp

Schmucker Art Catalogs Schmucker Art Gallery Fall 2020 Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica opularP Carolyn Hauk Gettysburg College Joy Zanghi Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs Part of the Book and Paper Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latina/o Studies Commons, and the Printmaking Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Hauk, Carolyn and Zanghi, Joy, "Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica opularP " (2020). Schmucker Art Catalogs. 35. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs/35 This open access art catalog is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica Popular Description During its most turbulent and formative years of the twentieth century, Mexico witnessed decades of political frustration, a major revolution, and two World Wars. By the late 1900s, it emerged as a modernized nation, thrust into an ever-growing global sphere. The revolutionary voices of Mexico’s people that echoed through time took root in the arts and emerged as a collective force to bring about a new self- awareness and change for their nation. Mexico’s most distinguished artists set out to challenge an overpowered government, propagate social-political advancement, and reimagine a stronger, unified national identity. Following in the footsteps of political printmaker José Guadalupe Posada and the work of the Stridentist Movement, artists Leopoldo Méndez and Pablo O’Higgins were among the founders who established two major art collectives in the 1930s: Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR) and El Taller de Gráfica opularP (TGP).