Caring for Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

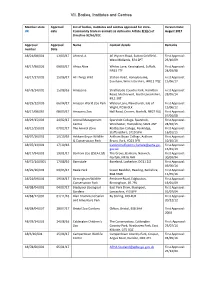

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Zoo Liability Supplemental Application (Complete in Addition to General Application and General Liability Renewal Application)

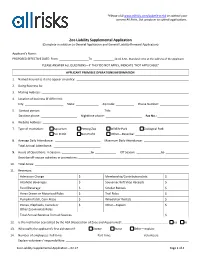

*Please visit www.allrisks.com/submit-a-risk or contact your current All Risks, Ltd. producer to submit applications. Zoo Liability Supplemental Application (Complete in addition to General Application and General Liability Renewal Application) Applicant’s Name: PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: From To 12:01 A.M., Standard Time at the address of the Applicant PLEASE ANSWER ALL QUESTIONS—IF THEY DO NOT APPLY, INDICATE “NOT APPLICABLE” APPLICANT PREMISES OPERATIONS INFORMATION 1. Named Insured as it is to appear on policy: 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: 4. Location of business (if different): City: State: Zip Code: Phone Number: 5. Contact person: Title: Daytime phone: Nighttime phone: Fax No.: 6. Website Address: 7. Type of Institution: Aquarium Petting Zoo Wildlife Park Zoological Park For Profit Non Profit Other—Describe: 8. Average Daily Attendance: Maximum Daily Attendance: Total Annual Attendance: 9. Hours of Operations: In Season: to Off Season: to Describe off-season activities or promotions: 10. Total Acres: 11. Revenues: Admission Charge $ Membership/Contributions/etc. $ Alcoholic Beverages $ Souvenier/Gift Shop Receipts $ Food/Beverage $ Stroller Rentals $ Horse Drawn or Motorized Rides $ Trail Rides $ Pumpkin Patch, Corn Maze $ Wheelchair Rentals $ Ponies, Elephants, Camels or $ Other—Explain: $ Other Zoo Animals Rides Total Annual Revenue from all Sources $ 12. Is the institution accredited by the AZA (Association of Zoos and Aquariums)? ........................................................ Yes No 13. Who staffs the applicant’s first aid station? Doctor Nurse Other—explain: 14. Number of employees: Full-time: Part-time: Volunteers: Explain volunteers’ responsibilities: Zoo Liability Supplemental Application – 02.17 Page 1 of 4 Do volunteers sign waivers of liability? ........................................................................................................................ -

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide Overview of Vancouver Vancouver is bustling, vibrant and diverse. This gem on Canada's west coast boasts the perfect combination of wild natural beauty and modern conveniences. Its spectacular views and awesome cityscapes are a huge lure not only for visitors but also for big productions, and it's even been nicknamed Hollywood North for its ever-present film crews. Less than a century ago, Vancouver was barely more than a town. Today, it's Canada's third largest city and more than two million people call it home. The shiny futuristic towers of Yaletown and the downtown core contrast dramatically with the snow-capped mountain backdrop, making for postcard-pretty scenes. Approximately the same size as the downtown area, the city's green heart is Canada's largest city park, Stanley Park, covering hundreds of acres filled with lush forest and crystal clear lakes. Visitors can wander the sea wall along its exterior, catch a free trolley bus tour, enjoy a horse-drawn carriage ride or visit the Vancouver Aquarium housed within the park. The city's past is preserved in historic Gastown with its cobblestone streets, famous steam-powered clock and quaint atmosphere. Neighbouring Chinatown, with its weekly market, Dr Sun Yat-Sen classical Chinese gardens and intriguing restaurants add an exotic flair. For some retail therapy or celebrity spotting, there is always the trendy Robson Street. During the winter months, snow sports are the order of the day on nearby Grouse Mountain. It's perfect for skiing and snowboarding, although the city itself gets more rain than snow. -

I Am a Compassionate Conservation Welfare Scientist

Opinion I Am a Compassionate Conservation Welfare Scientist: Considering the Theoretical and Practical Differences Between Compassionate Conservation and Conservation Welfare Ngaio J. Beausoleil Animal Welfare Science and Bioethics Centre, School of Veterinary Science, Massey University, Private Bag 11-222, Palmerston North 4410, New Zealand; [email protected] Received: 25 October 2019; Accepted: 28 January 2020; Published: 6 February 2020 Simple Summary: The well-being of individual wild animals is threatened in many ways, including by activities aiming to conserve species, ecosystems and biodiversity, i.e., conservation activities. Scientists working in two related disciplines, Compassionate Conservation and Conservation Welfare, are attentive to the well-being of individual wild animals. The purpose of this essay is to highlight the commonalities between these disciplines and to consider key differences, in order to stimulate discussion among interested parties and use our collective expertise and energy to best effect. An emerging scenario, the use of genetic technologies for control of introduced animals, is used to explore the ways each discipline might respond to novel conservation-related threats to wild animal well-being. Abstract: Compassionate Conservation and Conservation Welfare are two disciplines whose practitioners advocate consideration of individual wild animals within conservation practice and policy. However, they are not, as is sometimes suggested, the same. Compassionate Conservation and Conservation Welfare are based on different underpinning ethics, which sometimes leads to conflicting views about the kinds of conservation activities and decisions that are acceptable. Key differences between the disciplines appear to relate to their views about which wild animals can experience harms, the kinds of harms they can experience and how we can know about and confidently evidence those harms. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Jahresbericht 2017 – Sehr Gute Besuchszahlen, Konstante Entwicklung I

Tiergarten Nürnberg Das Jahr 2017 im Tiergarten Nürnberg: sehr gute Besuchszahlen, konstante Entwicklung 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Das Jahr 2017 im Tiergarten Nürnberg: sehr gute Besuchszahlen, konstante Entwicklung Vorworte 2 Dr. Dag Encke, Leitender Direktor, Tiergarten Nürnberg 2 Christian Vogel, Bürgermeister der Stadt Nürnberg 3 Teil 1 | Part 1 5 I. Bildung | Education 5 I.1 Teilnehmende | Participants 5 I.2 Programme | Programms 5 I.3 Weitere Bildungsarbeit | Further educational projects 7 II. Forschung | Research 11 II.1 Forschungsprojekte | Research projects 11 II.2 Kooperationen und Treffen | Co-operation and meetings 12 II.3 Yaqu Pacha 14 III. Tierhaltung | Keeping of animals 17 III.1 Tierbestand | Animal population 17 III.2 Arterhalt | Species conservation 18 III.3 Schlaglichter der Tierpflege 20 III.4 Schlaglichter der Tiermedizin | Veterinary 21 IV. Gesellschaftliche Relevanz | Social relevance 23 IV.1 Kommunikation und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit | 23 Communication and Public relations IV.2 Lobbying und Verbände | Lobbying and associations 27 IV.3 Verein der Tiergartenfreunde Nürnberg e.V. mit Tierpaten | 28 Association of the Friends pf Nuremberg Zoo and Godfathers for animals V. Freizeiteinrichtung | Recreational facility 31 V.1 Besuche und Kundenbindung | Visits and customer loyalty 31 V.2 Baumaßnahmen/Investitionen | Building measures and investments 34 VI. Funktionalität | Functionality 37 Impressum VI.1 Verwaltung | Administration 37 Herausgeber Tiergarten Nürnberg, Am Tiergarten 30, 90480 Nürnberg VI.2 Personal | Staff 37 Telefon (0911) 54 54 6 / Fax (0911) 54 54 802 • www.tiergarten.nuernberg.de VI.3 Konsumtion | Consumption 37 Gestaltung hills&trees design, [email protected] VI.4 Wirtschaftlichkeit (Einnahmen/Ausgaben) | Economics 41 Redaktion Dr. Nicola A. Mögel Teil 2 | Part 2 45 Text Dr. -

Read and Download Our New Report Here

A report to the Labour Animal Welfare Society May 2021 A review of the animal welfare, public health, and environmental, ecological and conservation implications of rearing, releasing and shooting non-native gamebirds in Britain Professor Stephen Harris BSc PhD DSc A REPORT TO THE LABOUR ANIMAL WELFARE SOCIETY A review of the animal welfare, public health, and environmental, ecological and conservation implications of rearing, releasing and shooting non-native gamebirds in Britain A report to the Labour Animal Welfare Society Professor Stephen Harris BSc PhD DSc May 2021 NON-NATIVE GAMEBIRDS IN BRITAIN - A REVIEW A REPORT TO THE LABOUR ANIMAL WELFARE SOCIETY Instructions Contents I was asked to review the scientific I was told that:- Summary of the key points 1 evidence on:- l I should identify any animal welfare concerns Sources of information 5 and potential effects on wildlife and public 1. The potential welfare and public health issues Introduction 6 associated with rearing, releasing and shooting health large numbers of non-native gamebirds in l I should identify the actual or potential The legal status of non-native gamebirds in Britain 7 Britain direct and indirect effects of activities Good-practice guidelines for gamebird shooting 10 2. Whether rearing and releasing large numbers associated with rearing, releasing and shooting gamebirds, and the distances of non-native gamebirds in Britain, and How many foxes are there in Britain? 12 associated predator-control activities, have an that may be required for any precautionary actions, prohibitions or mitigation impact on the numbers of different species How much food do foxes require? 16 of avian and mammalian predators, and the l I should consider any potential environmental, character and extent of any possible species ecological and/or conservation impacts of The number of pheasants and red-legged partridges 17 interactions widespread supplementary feeding by the reared, released and shot in Britain 3. -

Human Conflict and Animal Welfare Lecture Notes

Module 28 Human Conflict and Animal Welfare Lecture Notes Slide 1: This lecture was first developed for World Animal Protection by Dr David Main (University of Bristol) in 2003. It was revised by World Animal Protection scientific advisors in 2012 using updates provided by Dr Caroline Hewson. Slide 2: This module will introduce you to the ways in which collective human conflict affects animals. By human conflict, we mean fighting or war in a very broad sense, not domestic violence or aggression between private individuals. We will start by clarifying terminology because there are different kinds of human conflict. We will then focus on how animals may be affected by conflict. That is: • the ways in which animals are affected when conflict occurs in the region where they live • the ways in which animals are used actively in a conflict or the planning for conflict. We will conclude with examples of how we can help to improve animal welfare in areas where there is conflict. Slide 3: Starting with terminology: the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University in Sweden provides the online UCDP Conflict Encyclopedia. The following definitions are taken from there. Conflict has several characteristics, shown on the slide: • there is disagreement between at least two parties • the demands of each side cannot be met by the same resources at the same time. Typically, the resource is territory which contains a commodity needed for economic survival and growth, e.g. grazing for livestock; oil; minerals; water • the parties use armed force to solve their disagreement • this causes at least 25 battle-related human deaths in one year. -

MAC1 Abstracts – Oral Presentations

Oral Presentation Abstracts OP001 Rights, Interests and Moral Standing: a critical examination of dialogue between Regan and Frey. Rebekah Humphreys Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom This paper aims to assess R. G. Frey’s analysis of Leonard Nelson’s argument (that links interests to rights). Frey argues that claims that animals have rights or interests have not been established. Frey’s contentions that animals have not been shown to have rights nor interests will be discussed in turn, but the main focus will be on Frey’s claim that animals have not been shown to have interests. One way Frey analyses this latter claim is by considering H. J. McCloskey’s denial of the claim and Tom Regan’s criticism of this denial. While Frey’s position on animal interests does not depend on McCloskey’s views, he believes that a consideration of McCloskey’s views will reveal that Nelson’s argument (linking interests to rights) has not been established as sound. My discussion (of Frey’s scrutiny of Nelson’s argument) will centre only on the dialogue between Regan and Frey in respect of McCloskey’s argument. OP002 Can Special Relations Ground the Privileged Moral Status of Humans Over Animals? Robert Jones California State University, Chico, United States Much contemporary philosophical work regarding the moral considerability of nonhuman animals involves the search for some set of characteristics or properties that nonhuman animals possess sufficient for their robust membership in the sphere of things morally considerable. The most common strategy has been to identify some set of properties intrinsic to the animals themselves. -

Housing, Husbandry and Welfare of a “Classic” Fish Model, the Paradise Fish (Macropodus Opercularis)

animals Article Housing, Husbandry and Welfare of a “Classic” Fish Model, the Paradise Fish (Macropodus opercularis) Anita Rácz 1,* ,Gábor Adorján 2, Erika Fodor 1, Boglárka Sellyei 3, Mohammed Tolba 4, Ádám Miklósi 5 and Máté Varga 1,* 1 Department of Genetics, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter stny. 1C, 1117 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] 2 Budapest Zoo, Állatkerti krt. 6-12, H-1146 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] 3 Fish Pathology and Parasitology Team, Institute for Veterinary Medical Research, Centre for Agricultural Research, Hungária krt. 21, 1143 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] 4 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Helwan University, Helwan 11795, Egypt; [email protected] 5 Department of Ethology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter stny. 1C, 1117 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (M.V.) Simple Summary: Paradise fish (Macropodus opercularis) has been a favored subject of behavioral research during the last decades of the 20th century. Lately, however, with a massively expanding genetic toolkit and a well annotated, fully sequenced genome, zebrafish (Danio rerio) became a central model of recent behavioral research. But, as the zebrafish behavioral repertoire is less complex than that of the paradise fish, the focus on zebrafish is a compromise. With the advent of novel methodologies, we think it is time to bring back paradise fish and develop it into a modern model of Citation: Rácz, A.; Adorján, G.; behavioral and evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) studies. The first step is to define the Fodor, E.; Sellyei, B.; Tolba, M.; housing and husbandry conditions that can make a paradise fish a relevant and trustworthy model. -

Veganism: a New Approach to Health Miljana Z

Chapter Veganism: A New Approach to Health Miljana Z. Jovandaric Abstract The word vegan was given by Donald Watson in 1944 in Leicester, England, who, together with several other members of the Vegetarian Society, wanted to establish a group of vegetarians who did not consume milk or dairy products. When the proposal was rejected, Watson and like-minded people founded The Vegan Society, which advocated a complete plant-based diet, excluding meat, fish, eggs, milk and dairy products (cheese, butter) and honey. Vegans do not wear fur items, wool, bone, goat, coral, pearl or any other material of animal origin. According to surveys, vegans make up between 0.2% and 1.3% of the US population and between 0.25% and 7% of the UK population. Vegan foods contain lower levels of cholesterol and fat than the usual diet. Keywords: veganism, health, supplements 1. Introduction Veganism is a philosophy and lifestyle that seeks to exclude the use of animals for food or clothing and includes all other forms of diet of non-animal origin. Vegan diet is based on cereals, legumes, fruits and vegetables. Vegans do not eat meat, fish, seafood, eggs, milk, dairy products, honey threads carry things made of fur, wool, bones, leather, coral, pearls or any other materials of animal origin. Within the commitment to a vegan lifestyle, there is a group of people who eat exclusively fresh raw fruits, vegetables without heat treatment. This group of vegans is called a row food diet. Veganism differs from vegetarianism in that it is reduced entirely to a plant-based diet, while vegetarians also eat some products of animal origin, when animals are not killed when obtaining these products, e.g.