Chapter 3. Key Recommendations and Overarching Themes for a More Resilient Comoros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ing in N the E

Migrant fishers and fishing in the Western Indian Ocean: Socio-economic dynamics and implications for management Februaryr , 2011 PIs: Innocent Wanyonyi (CORDIO E.A, Kenya / Linnaeus University, Sweden) Dr Beatrice Crona (Stockholm Resilience Center, University of Stockholm, Sweden) Dr Sérgio Rosendo (FCSH, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal / UEA, UK) Country Co‐Investigators: Dr Simeon Mesaki (University of Dar es Salaam)‐ Tanzania Dr Almeida Guissamulo (University of Eduardo Mondlane)‐ Mozambique Jacob Ochiewo (Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute)‐ Kenya Chris Poonian (Community Centred Conservation)‐ Comoros Garth Cripps (Blue Ventures) funded by ReCoMaP ‐Madagascar Research Team members: Steven Ndegwa and John Muturi (Fisheries Department)‐ Kenya Tim Daw (University of East Anglia, UK)‐ Responsible for Database The material in this report is based upon work supported by MASMA, WIOMSA under Grant No. MASMA/CR/2008/02 Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendation expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the WIOMSA. Copyright in this publication and in all text, data and images contained herein, except as otherwise indicated, rests with the authors and WIOMSA. Keywords: Fishers, migration, Western Indian Ocean. Page | 1 Recommended citation: WIOMSA (2011). Migrant fishers and fishing in the Western Indian Ocean: Socio‐economic dynamics and implications for management. Final Report of Commissioned Research Project MASMA/CR/2008/02. Page | 2 Table of Contents -

Centre Souscentreserie Numéro Nom Et Prenom

Centre SousCentreSerie Numéro Nom et Prenom MORONI Chezani A1 2292 SAID SAMIR BEN YOUSSOUF MORONI Chezani A1 2293 ADJIDINE ALI ABDOU MORONI Chezani A1 2297 FAHADI RADJABOU MORONI Chezani A4 2321 AMINA ASSOUMANI MORONI Chezani A4 2333 BAHADJATI MAOULIDA MORONI Chezani A4 2334 BAIHAKIYI ALI ACHIRAFI MORONI Chezani A4 2349 EL-ANZIZE BACAR MORONI Chezani A4 2352 FAOUDIA ALI MORONI Chezani A4 2358 FATOUMA MAOULIDA MORONI Chezani A4 2415 NAIMA SOILIHI HAMADI MORONI Chezani A4 2445 ABDALLAH SAID MMADINA NABHANI MORONI Chezani A4 2449 ABOUHARIA AHAMADA MORONI Chezani A4 2450 ABOURATA ABDEREMANE MORONI Chezani A4 2451 AHAMADA BACAR MOUKLATI MORONI Chezani A4 2457 ANRAFA ISSIHAKA MORONI Chezani A4 2458 ANSOIR SAID AHAMADA MORONI Chezani A4 2459 ANTOISSI AHAMADA SOILIHI MORONI Chezani D 2509 NADJATE HACHIM MORONI Chezani D 2513 BABY BEN ALI MSA MORONI Dembeni A1 427 FAZLAT IBRAHIM MORONI Dembeni A1 464 KASSIM YOUSSOUF MORONI Dembeni A1 471 MOZDATI MMADI ADAM MORONI Dembeni A1 475 SALAMA MMADI ALI MORONI Dembeni A4 559 FOUAD BACAR SOILIHI ABDOU MORONI Dembeni A4 561 HAMIDA IBRAHIM MORONI Dembeni A4 562 HAMIDOU BACAR MORONI Dembeni D 588 ABDOURAHAMANE YOUSSOUF MORONI Dembeni D 605 SOIDROUDINE IBRAHIMA MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 640 ABDOU YOUSSOUF MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 642 ACHRAFI MMADI DJAE MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 643 AHAMADA MOUIGNI MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 654 FAIDATIE ABDALLAH MHADJOU MORONI FoumbouniA4 766 ABDOUCHAKOUR ZAINOUDINE MORONI FoumbouniA4 771 ALI KARIHILA RABOUANTI MORONI FoumbouniA4 800 KARI BEN CHAFION BENJI MORONI FoumbouniA4 840 -

Comoros Business Profile

COMOROS BUSINESS PROFILE Country official Name Union of the COMOROS Area 1 861 km² Population 0.851 Million Inhabitants Time UTC+3 Capital Moroni Comoros Franc (KMF) Currency 1 KMF = 0,0024 USD, 1 USD = 417,5767 KMF Language Arabic, French Major cities Moutsamoudou, Fomboni, Domoni, Tsimbeo, Adda-Douéni, Sima, Ouani, Mirontsi Member since 1976 OIC Member State Date Bilateral Investment Treaties Within OIC United Arab Emirates, Burkina Faso, Egypt Member States TPSOIC and protocols (PRETAS and Rules of Signed, not Ratified Origin) WTO Observer Regional and bilateral trade Agreements Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) GDP growth (annual %) 2.50 % in 2019 The country mainly exports cloves (45%), vanilla (32.3%), essential oils (12.3%), machines for cleaning or Economic sectors grading seeds (2%), and motor vehicles (1.7%). Its main imports include motor vehicles (11.9%), electric sound or visual signalling apparatus (11.6%), rice (9.3%), cement (7.1%), and meat (5%). 2019 World Exports USD 49 Millions World Imports USD 204 Millions Market Size USD 253 Millions Intra-OIC Exports USD 3.7 Millions Intra-OIC Exports share 7.43% UAE, Pakistan, Benin, Sudan, Oman, Turkey, Malaysia, Uganda, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Morocco, Egypt, Top OIC Customers Mozambique, Tunisia, Bangladesh Cloves, whole fruit, cloves and stems, Vanilla, Motor vehicles for the transport of goods, incl. chassis with engine and cab, Containers, incl. containers for the transport of fluids, specially designed and equipped for . Flat-rolled products of iron or non-alloy steel, of a width of >= 600 mm, cold-rolled "cold- reduced", Trunks, suitcases, vanity cases, executive-cases, briefcases, school satchels, spectacle Major Intra-OIC exported products cases, Fuel wood, in logs, billets, twigs, faggots or similar forms; wood in chips or particles; sawdust . -

Comoros 2018 Human Rights Report

COMOROS 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Union of the Comoros is a constitutional, multiparty republic. The country consists of three islands--Grande Comore (also called Ngazidja), Anjouan (Ndzuani), and Moheli (Mwali)--and claims a fourth, Mayotte (Maore), that France administers. In 2015 successful legislative elections were held. In April 2016 voters elected Azali Assoumani as president of the union, as well as governors for each of the three islands. Despite a third round of voting on Anjouan--because of ballot-box thefts--Arab League, African Union, and EU observer missions considered the elections generally free and fair. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. On July 30, Comorians passed a referendum on a new constitution, which modified the rotating presidency, abolished the islands’ vice presidents, and significantly reduced the size and authority of the islands’ governorates. On August 6, the Supreme Court declared the referendum free and fair, although the opposition, which had called for a boycott of the referendum, rejected the results and accused the government of ballot-box stuffing. Human rights issues included torture; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; political prisoners; use of excessive force against detainees; restrictions on freedom of movement; corruption; criminalization of same-sex sexual conduct, trafficking in persons, and ineffective enforcement of laws protecting workers’ rights. Impunity for violations of human rights was widespread. Although the government discouraged officials from committing human rights violations and sometimes arrested or dismissed officials implicated in such violations, they were rarely tried. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. -

South Africa 12 Nights / 13 Days

SOUTH AFRICA 12 NIGHTS / 13 DAYS 304, SUKH SAGAR BUILDING, 3RD FLOOR, N. S. PATKAR MARG, HUGHES ROAD, CHOWPATTY, MUMBAI – 400 007. TEL: 2369 7578 / 2361 7578 / 2368 2421 / 2367 2160 / 2362 2160 / 2362 2421 / 9920045551 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE : www.comfort-voyages.com DEPARTURE DATES APRIL: 16, 20, 24, 28 MAY: 02, 04, 06, 08, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30 JUNE: 03, 07, 11, 15, 19, 23 DAY 00: MUMBAI – ADDIS ABABA Arrive at Mumbai International Airport to board flight to Addis Ababa. On arrival into Addis Ababa airport proceed for your connecting flight to Cape Town. DAY 01: ADDIS ABABA – CAPE TOWN Arrive into Cape Town & proceed to clear your customs & immigration. Later board your coach and proceed towards your hotel & check in. Evening free at Leisure. Dinner and Overnight in Cape Town. DAY 02 : CAPE TOWN After breakfast proceed to the cable car station, for a cable car ride up Table Mountain (if weather permits), It gives breath-taking views over the city and its beaches. Later we proceed for an Orientation City Tour visiting Houses of Parliament, the Castle, Signal Hill, Sea Point, V&A Water Front & Malay Quarters. Later proceed for Helicopter Ride (Included) and evening free at leisure. Dinner and Overnight in Cape Town. DAY 03 : CAPE TOWN After breakfast we drive towards Hout Bay and take a boat trip to Seal Island a 45 minutes boat trip. The island is long and narrow, 800 meter long and only 50 meter wide. Some rock made by sealers in the 1930s are still evident. -

Plan D'aménagement Et De Gestion Du Parc National Cœlacanthe 2017

Parcs Nationaux RNAPdes Comores UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement Vice-Présidence Chargée du Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Pêche, de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme Parcs Nationaux des Comores Plan d’Aménagement et De Gestion du Parc National Cœlacanthe 2017-2021 Janvier 2018 Les avis et opinions exprimés dans ce document sont celles des auteurs, et ne reflètent pas forcément les vues de la Vice Présidence - Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Pêche, de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme, ni du PNUD, ni du FEM (UNDP - GEF) Mandaté par L’Union des Comores, Vice-Présidence Chargée du Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Pêche, de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme, Parcs nationaux des Comores Et le Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement, PNUD Fonds Mondial pour l’Environnement, FEM Maison du PNUD, Hamramba BP. 648, Moroni, Union des Comores T +269 7731558/9, F +269 7731577 www.undp.org Titre du Projet d’appui RNAP Développement d’un réseau national d’aires protégées terrestres et marines représentatives du patrimoine naturel unique des Comores et cogérées par les communautés villageoises locales. PIMS : 4950, ID ATLAS : 00090485 Citation : Parcs nationaux des Comores (2017). Plan d’Aménagement et de Gestion du Parc National Cœlacanthe. 2017-2021. 134 p + Annexes 98 p. Pour tous renseignements ou corrections : Lacroix Eric, Consultant international UNDP [email protected] Fouad ABDOU RABI, Coordinateur RNAP [email protected] Plan d’aménagement et de gestion du Parc national Cœlacanthe - 2017 2 Avant-propos Depuis 1994 le souhait des Comoriennes et Comoriens et de leurs amis du monde entier est de mettre en place un Système pour la protection et le développement des aires protégées des Comores. -

WIND SPEED POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT of SELECTED CLIMATIC ZONES of ETHIOPIA Endalew Ayenew1, Santoshkumar Hampannavar2 •

Endalew Ayenew RT&A, Special Issue № 1 (60) WIND SPEED POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT Volume 16, Janyary 2021 WIND SPEED POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT OF SELECTED CLIMATIC ZONES OF ETHIOPIA Endalew Ayenew1, Santoshkumar Hampannavar2 • 1College of Electrical & Mechanical Engineering, Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Ethiopia Professor, School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, REVA University, Bengaluru, India [email protected] Abstract In this paper the wind speed potential assessment of different climatic zones of Ethiopia are proposed. Statistical analysis of wind speed were carried out using Rayleigh and Weibull probability density functions (PDF) for a specific location. Real time Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) data was used for the wind speed potential assessment of three different climatic zones and to plot wind rose diagram. Keywords: Wind speed assessment, Statistical analysis, Wind Energy I. Introduction Wind is one of the globally recognized potential renewable energy source and it is important to have an inclusive knowledge about the wind characteristics for efficient planning and implementation of wind power generation plants. The wind energy assessment is very crucial and draws attention of researchers. Wind resources assessment is a basic requirement for the following reasons: i) wind power is proportional to the cube of the wind speed (10% difference in wind speed leads to 33% changes in wind power), ii) fluctuating wind speed and wind shears. According to the statistics the country has existing wind energy capacity of about 18.7GW with wind speed of 7.5 to 8.8 m/s at 50m height above the ground level. Wind energy is recognized throughout the world as a cost-effective energy plant. -

Résultats CCD 5

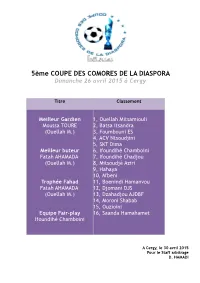

5ème COUPE DES COMORES DE LA DIASPORA Dimanche 26 avril 2015 à Cergy Titre Classement Meilleur Gardien 1, Ouellah Mitsamiouli Moussa TOURE 2, Batsa Itsandra (Ouellah M.) 3, Foumbouni ES 4, ACV Ntsoudjini 5, SKT Dima Meilleur buteur 6, Ifoundihé Chamboini Fatah AHAMADA 7, Ifoundihé Chadjou (Ouellah M.) 8, Mitsoudjé Aziri 9, Hahaya 10, M'beni Trophée Fahad 11, Boenindi Hamanvou Fatah AHAMADA 12, Djomani DJS (Ouellah M.) 13, Dzahadjou AJDBF 14, Moroni Shabab 15, Ouzioini Equipe Fair-play 16, Saanda Hamahamet Ifoundihé Chamboini A Cergy, le 30 avril 2015 Pour le Staff arbitrage D. HAMADI CCD 2015 / POULE A Tableau des matches Matches Équipes Scores Équipes Foumbouni E-S 2 – 0 AJDBF Dzahadjou Ouzioini 0 – 1 Mitsoudjé AZIRI AJDBF Dzahadjou 0 – 2 Mitsoudjé AZIRI Foumbouni E-S 3 – 0 Ouzioini Foumbouni E-S 2 – 2 Mitsoudjé AZIRI Ouzioini 1 – 1 AJDBF Dzahadjou Tableau des points 1er Match 2ème Match 3ème Match Total Diff. Foumbouni E-S 3 3 1 7 7 AJDBF Dzahadjou 0 0 1 1 / Ouzioini 0 0 1 1 / Mitsoudjé AZIRI 3 3 1 7 5 Rappel : victoire : + 3 / nul : + 1 / défaite : 0 Premier : Foumbouni ES / Deuxième : Mitsoudjé AZIRI CCD 2015 / POULE B Tableau des matches Matches Équipes Scores Équipes Ifoundihé Chamboini 1 – 1 Ifoundihé Chadjou Djomani DJS 1 – 0 Hahaya Ifoundihé Chadjou 0 – 1 Hahaya Djomani DJS 0 – 1 Ifoundihé Chamboini Ifoundihé Chadjou 5 – 2 Djomani DJS Hahaya 0 – 0 Ifoundihé Chamboini Tableau des points 1er Match 2ème Match 3ème Match Total Diff. Ifoundihé Chamboini 1 3 1 5 / Ifoundihé Chadjou 1 0 3 4 6 Djomani DJS 3 0 0 3 3 Hahaya 0 3 1 4 / Rappel : victoire : + 3 / nul : + 1 / défaite : 0 Premier : Ifoundihé Chamboini / Deuxième : Ifoundihé Chadjou CCD 2015 / POULE C Tableau des matches Matches Équipes Scores Équipes Batsa Itsandra 0 – 0 ACV Ntsoudjini Moroni Al-Shabab 2 – 1 Saada Hamahamet ACV Ntsoudjini 2 – 0 Saada Hamahamet Batsa Itsandra 2 – 0 Moroni Al-Shabab Moroni Al-Shabab 1 – 3 ACV Ntsoudjini Saada Hamahamet 0 – 2 Batsa Itsandra Tableau des points 1er Match 2ème Match 3ème Match Total Diff. -

Mission 1 Cadre Institutionnel

UNION DES COMORES --------------------- VICE –PRESIDENCE EN CHARGE DU MINISTERE DE LA PRODUCTION, DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT, DE L’ENERGIE, DE L’INDUSTRIE ET DE L’ARTISANAT ------------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DE L’ENERGIE, DES MINES ET DE L’EAU (DGEME) UNITE DE GESTION DU PROJET ALIMENTATION EN EAU POTABLE ET ASSAINISSEMENT --------------------- PROJET D ’A LIMENTATION EN EAU POTABLE ET D SSAINISSEMENT DANS LES ILES DE ’A (AEPA) 3 L’U NION DES COMORES (F INANCEMENT BAD) ETUDES TECHNIQUES, DU CADRE INSTITUTIONNEL ET DU PROGRAMME NATIONAL D’AEPA Mission 1 : Elab oration du cadre institutionnel, o rganisationnel et financier du s ecteur d’AEPA Edition définitive JUIN 2013 71, Avenue Alain Savary Bloc D – 2ème étage - App 23 ENTREPRISE D’ETUDES DE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL 1003 Cité El Khadra - Tunis EEDR MAMOKATRA S.A. Tél : (216) 71 809 686 Société Anonyme au capital de 20.000.000 d’Ariary Fax : (216) 71 806 313 Siège social : Villa Mamokatra Nanisana E-mail : [email protected] 101 ANTANANARIVO Site web : www.hydroplante.com …: (261.20) 22 402-14 ; 22 403-78 * 961 E-mail : [email protected] 1 Elaboration du cadre institutionnel, organisationnel et financier du secteur de l’AEPA des Comores PAEPA PREFACE L’élaboration du cadre institutionnel, organisationnel et financier du secteur d’eau potable et d’Assainissement s’inscrit dans le cadre de la composante 1 du Projet d’Alimentation en Eau Potable et d’Assainissement (PAEPA – Comores – projet n : P-KM-EA0-001) financé par un don de la Banque Africaine de Développement. Tel que défini par le rapport d’évaluation du projet, le PAEPA comprend quatre (4) composantes: (i) l’Etude du Cadre institutionnel, organisationnel et financier ainsi que l’élaboration d’un plan stratégique à l’horizon 2030; (ii) le développement et la réhabilitation des infrastructures d’alimentation en eau potable et d’assainissement (AEPA) de plusieurs localités dont Moroni, Ouani, Mutsamudu, Fomboni et Mbéni; (iii) l’Appui Institutionnel et (iv) la Gestion du Projet. -

Comoros Mission Notes

Peacekeeping_4.qxd 1/14/07 2:29 PM Page 109 4.5 Comoros The 2006 elections in the Union of the support for a solution that preserves the coun- Comoros marked an important milestone in the try’s unity. After Anjouan separatists rejected peace process on the troubled archipelago. New an initial deal in 1999, the OAU, under South union president Ahmed Abdallah Mohamed African leadership, threatened sanctions and Sambi won 58 percent of the vote in elections, military action if the island continued to pur- described by the African Union as free and fair, sue secession. All parties eventually acceded and took over on 27 May 2006, in the islands’ to the 2001 Fomboni Accords, which provided first peaceful leadership transition since 1975. for a referendum on a new constitution in The AU Mission for Support to the Elections in advance of national elections. the Comoros (AMISEC), a short-term mission The core of the current deal is a federated devoted to the peaceful conduct of the elections, structure, giving each island substantial auton- withdrew from Comoros at the end of May, hav- omy and a turn at the presidency of the union, ing been declared a success by the AU and the which rotates every four years. Presidential Comorian government. The Comoros comprises three islands: Grande Comore (including the capital, Moroni), Anjouan, and Moheli. Following independ- ence from France in 1975, the country experi- enced some twenty coups in its first twenty- five years; meanwhile, Comoros slid ever deeper into poverty, and efforts at administra- tive centralization met with hostility, fueling calls for secession and/or a return to French rule in Anjouan and Moheli. -

Eies) Et Plan De Gestion Environnementale Et Sociale (Pges) Du Projet Comoresol – Grandes Comores

UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement ---------------- MINISTERE DES FINANCES ET DU BUDGET ---------------- PROGRAMME REGIONAL D’INFRASTRUCTURES DE COMMUNICATION RCIP-4 ------ ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL (EIES) ET PLAN DE GESTION ENVIRONNEMENTALE ET SOCIALE (PGES) DU PROJET COMORESOL – GRANDES COMORES Version finale Novembre 2019 SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE 1 - RESUME EXECUTIF EN FRANCAIS ..................................................................... 7 2 - UFUPIZI WA MTRILIYO NDZIANI .................................................................... 27 3 - CONTEXTE GENERAL, OBJECTIFS ET METHODOLOGIE D’ELABORATION DE L’EIES ........................................................................................................................ 46 4 - BREVE DESCRIPTION DU PROJET ................................................................... 51 5 - CADRE JURIDIQUE ET LES POLITIQUES DE SAUVEGARDE DE LA BANQUE MONDIALE .............................................................................................................. 81 6 - DESCRIPTION ET ANALYSE DE L’ETAT INITIAL DU SITE ET DE SON ENVIRONNEMENT .................................................................................................. 97 7 - CONSULTATION DU PUBLIC .......................................................................... 154 8 - ANALYSE ET EVALUATION DES IMPACTS ENVIRONNEMENTAUX ET SOCIAUX DU PROJET ........................................................................................... 155 ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL -

Socmon Comoros NOAA

© C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands Programme 2010 C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands Programme is a collaborative initiative between Community Centred Conservation (C3), a non-profit company registered in England no. 5606924 and local partner organizations. The study described in this report was funded by the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program. Suggested citation: C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands Programme (2010) SOCIO- ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT AND IDENTIFICATION OF POTENTIAL SITES FOR COMMUNITY-BASED CORAL REEF MANAGEMENT IN THE COMOROS. A Report Submitted to the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program, USA 22pp FOR MORE INFORMATION C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program Islands Programme (Comoros) Office of Response and Restoration BP8310 Moroni NOAA National Ocean Service Iconi 1305 East-West Highway Union of Comoros Silver Spring, MD 20910 T. +269 773 75 04 USA CORDIO East Africa Community Centred Conservation #9 Kibaki Flats, Kenyatta Beach, (C3) Bamburi Beach www.c-3.org.uk PO BOX 10135 Mombasa 80101, Kenya [email protected] [email protected] Cover photo: Lobster fishers in northern Grande Comore SOCIO-ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT AND IDENTIFICATION OF POTENTIAL SITES FOR COMMUNITY-BASED CORAL REEF MANAGEMENT IN THE COMOROS Edited by Chris Poonian Community Centred Conservation (C3) Moroni 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report is the culmination of the advice, cooperation, hard work and expertise of many people. In particular, acknowledgments are due to the following for their contributions: COMMUNITY CENTRED