43 Education in the Baltic Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Links Between Italian and Polish Cartography

ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 83 STANISLAW LESZCZYCKI LINKS BETWEEN ITALIAN AND POLISH CARTOGRAPHY IN THE 15TH AND 16TH CENTURIES OSSOLINEUM ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA Direttore : Bronislaw Bilinski » 2, Vicolo Ooria (Palazzo Doria) 00187 Roma Tel. 679.21.70 \ / Accademia polacca delle scienze BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 83 \ STANISLAW LESZCZYCKI LINKS BETWEEN ITALIAN AND POLISH CARTOGRAPHY IN THE 15TH AND 16TH CENTURIES WROCLAW • WARSZAWA . KRAKÓW . GDANSK . LÓDt ZAKÌAD NARODOWY I MIEN IA OSSOL1NSKICH WYDAWNICTWO POLSKIEJ AKADEMII NAUK 1981 CONSIGLIO DI REDAZIONE Alcksander Gicyszton ' presidente Witold Hensel Mieczyslaw Klimowicz Jcrzy Kolodzicjczak Roman Kulikowski Leszek Kuznicki Wladyslaw Markiewicz Stanislaw Mossakowski Maciej Nal^cz M i rostaw Nowaczyk Antoni Sawczuk Krzysztof Zaboklicki REDATTORE Bronistaw Biliriski The first contacts. Contacts between Italian and Polish cartography can be traced back as far as the early 15th century. Documents have survived to show that in 1421 a Polish delegation to Rome presented a hand-drawn map to Pope Martin V in an effort to clarify Poland's position in her with the Teutonic dispute Knights. The Poles used probably a large colour show map to that the Teutonic Knights were unlawfully holding lands that belonged to Poland and that had never been granted to them. The map itself is unfortunately no longer extant. An analysis of the available documentation made , by Professor Bozena Strzelecka has led her to helieve that the could map not have been made in Poland as cartography in fact did not exist there at that time yet. -

Review Essay

Studia Judaica (2017), Special English Issue, pp. 117–130 doi:10.4467/24500100STJ.16.020.7372 REVIEW ESSAY Piotr J. Wróbel Modern Syntheses of Jewish History in Poland: A Review* After World War II, Poland became an ethnically homogeneous state. National minorities remained beyond the newly-moved eastern border, and were largely exterminated, forcefully removed, or relocated and scattered throughout the so-called Recovered Territories (Polish: Ziemie Odzys kane). The new authorities installed in Poland took care to ensure that the memory of such minorities also disappeared. The Jews were no exception. Nearly two generations of young Poles knew nothing about them, and elder Poles generally avoided the topic. But the situation changed with the disintegration of the authoritarian system of government in Poland, as the intellectual and informational void created by censorship and political pressure quickly filled up. Starting from the mid-1980s, more and more Poles became interested in the history of Jews, and the number of publica- tions on the subject increased dramatically. Alongside the US and Israel, Poland is one of the most important places for research on Jewish history. * Polish edition: Piotr J. Wróbel, “Współczesne syntezy dziejów Żydów w Polsce. Próba przeglądu,” Studia Judaica 19 (2016), 2: 317–330. The special edition of the journal Studia Judaica, containing the English translation of the best papers published in 2016, was financed from the sources of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education for promotion of scientific research, according to the agreement 508/P-DUN/2016. 118 PIOTR J. WRÓBEL Jewish Historiography during the Polish People’s Republic (PRL) Reaching the current state of Jewish historiography was neither a quick nor easy process. -

Marceli Kosman Aleksander Gieysztor and Gerard Labuda for the 100Th Anniversary of Two Great Historians' Birthdays (1919–201

Marceli Kosman Aleksander Gieysztor and Gerard Labuda for the 100th anniversary of two great historians’ birthdays (1919–2016) Historia Slavorum Occidentis 2(11), 243-264 2016 Historia Slavorum Occidentis 2016, nr 2(11) ISSN 2084–1213 DOI: 10.15804/hso160211 MARCELI KOSMAN (POZNAŃ) AALEKSANDERLEKSANDER GGIEYSZTORIEYSZTOR AANDND GGERARDERARD LLABUDAABUDA FFOROR TTHEHE 1100TH00TH AANNIVERSARYNNIVERSARY OOFF TTWOWO GGREATREAT HHISTORIANS’ISTORIANS’ BBIRTHDAYSIRTHDAYS ((1916–2016)1916–2016) Słowa kluczowe: mediewistyka, nauka i polityka, kultura historyczna, kultura polityczna Keywords: Medievalism, science and politics, historical culture, political culture Abstract: Gerard Labuda and Aleksander Gieysztor were among the most distin- guished Polish historians. Their impact on the development of Polish Medieval stud- ies has been tremendous as testifi ed by a large group of their disciples who continue the research commenced by the Poznań and Warsaw historians. These two historians and friends, both born in 1916, were among the most eminent medievalists in Poland in the 20th century. Their academic debut came in the years preceding the outbreak of WWII, while their careers pro- gressed brilliantly in the years following the end of the war. For several dec- ades, they marked their academic presence as the authors of great works, and they held the most prominent offi ces in academic life in Poland while being highly renowned in the international arena. They took an active part in the process of political transition, leading to Poland regaining full sovereignty in 1989, and they approved of its evolutionary mode. They were unquestion- able moral authorities for their circles and beacons in public activities. Al- eksander Gieysztor died ten years after the transformation (1999), followed another eleven years later by Gerard Labuda (2010), who remained active until his last days, although he was gradually limiting his organizational 244 MARCELI KOSMAN posts. -

Zessin-Jurek on Dabrowski, 'Poland: the First Thousand Years'

Habsburg Zessin-Jurek on Dabrowski, 'Poland: The First Thousand Years' Review published on Thursday, January 21, 2016 Patrice M. Dabrowski. Poland: The First Thousand Years. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2014. 506 pp. $45.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-87580-487-3. Reviewed by Lidia Zessin-Jurek (Deutsch-Polnisches Forschungsinstitut am Collegium Polonicum) Published on HABSBURG (January, 2016) Commissioned by Jonathan Kwan Polish History for the General Reader The desire to write yet another single-volume history of one country may arise from several motivations, most obviously among them: market needs, challenging traditional narratives, and—finally—a genuine author’s sympathy to the object of study. In the case of Patrice M. Dabrowski’s undertaking, the third reason seems to be the most fitting. From the book’s first pages, the reader will appreciate the author’s undaunted enthusiasm in dealing with a thousand years of Poland’s history. Dabrowski starts her synthesis with the observation that Poland occasionally serves as a metaphorical “nowhere.” Outside native historiography, on the one hand, the first mentions of Poland generally appear—paradoxically—when this once strong and large state ceased to exist, partitioned by its neighbors in the late eighteenth century. Polish historiography, on the other hand, has undoubtedly privileged a very national—if not out-and-out nationalistic—perspective, often losing sight of the outside factors influencing the course of Poland’s historical development. Consequently, there remains a need for historical overviews that do not marginalize the Polish experience while at the same time placing Poland’s history in a larger European context. -

Touring the Lands of the Old Rzeczpospolita: a Historic Travelogue Michael Rywkin Starting out on a a Warm Day in July 1997

Touring the Lands of the old Rzeczpospolita: a historic travelogue Michael Rywkin Starting out On a a warm day in July 1997, I was sitting in a tourist bus going from Warsaw, Poland, to Vilnius, Lithuania, with two dozen young graduate students recruited from the western republics of the former Soviet Union. The bus was chartered by the University of Warsaw Eastern Summer School for a mobile session to be held in Warsaw, Vilnius, Minsk, and Lviv, after which we would travel back to Warsaw. Our twenty or so students (or rather, auditors, since they were all at the advanced graduate level) comprised an assortment of nationalities, abilities, characters, and appearances. Among them were a very energetic young lady radio producer from Minsk, an assertive student of nationalism from Kiev, a couple of tall literature-minded Russian girls from Moscow, an inquisitive Bulgarian pair, and a friendly, picture-pretty Ukrainian teacher, to name just a few. The accompanying staff consisted of several Polish professors (each joining us for a portion of the trip) and myself (I was taking the risk of remaining for the entire length of the expedition). Our academic organizer, Jan Malicki, was doggedly determined to make us consume the totality of the cultural menu without neglecting to visit a single site; Inga Kotanska, the financial organizer adept at joggling with all the soft currencies of the region, was to assume our solvency; and Wojciech Stanislawski, the administrative assistant, was in charge of the physical well-being of the travelers. A Polish Radio reporter was also aboard. The chartered bus had seen better days, but it was air-conditioned and shook only moderately. -

BIULETYN ARCHIWUM POLSKIEJ AKADEMII NAUK NR 59 Warszawa 2018

BIULETYN ARCHIWUM POLSKIEJ AKADEMII NAUK NR 59 Warszawa 2018 Przygotowuje Komitet Redakcyjny w składzie Joanna Arvaniti, Anita Chodkowska, Hanna Krajewska, Katarzyna Słojkowska Redakcja Joanna Arvaniti Korekta Joanna Arvaniti, Tomasz Rudzki Tłumaczenie Urszula Pawlik Adres Redakcji Archiwum PAN 00-330 Warszawa, ul. Nowy Świat 72 Wydano z dotacji Ministerstwa Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego ISSN: 0551-3782 Skład, łamanie i druk AMALKER 03-715 Warszawa, ul. Okrzei 21/4 www.amalker.com Spis treści Wykaz ważniejszych skrótów występujących w inwentarzach ........ 5 Joanna Arvaniti Inwentarze archiwalne .................................................................... 6 Katarzyna Słojkowska Materiały Kazimierza Albina i Hanny Dobrowolskich ................... 8 Katarzyna Słojkowska Materiały Romana i Jadwigi Kobendzów ..................................... 22 Alicja Kulecka Archiwa osobiste — problemy gromadzenia i opracowywania .... 48 Izabela Gass Abacja w czasach belle époque ..................................................... 59 Mateusz Sobeczko Wyjazdy naukowe śląskich akademików do Stanów Zjednoczonych i Wielkiej Brytanii — na podstawie zasobu Polskiej Akademii Nauk Archiwum w Warszawie Oddziału w Katowicach ................................................................................ 67 Mateusz Sobeczko Fotografia jako źródło historyczne — na podstawie zasobu Polskiej Akademii Nauk Archiwum w Warszawie Oddziału w Katowicach ................................................................................ 77 Joanna Arvaniti Wystawy -

Acta 123.Indd

SHORT NOTES SHORT NOTES* Acta Poloniae Historica 123, 2021 PL ISSN 0001–6829 GENERAL WORKS1 Jarosław Kłaczkow (ed.), Ewangelicy w regionie kujawsko-pomorskim na przestrzeni wieków [Protestants in the Cuiavian-Pomeranian Region Through the Centuries], Toruń, 2020, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 512 pp., ills, bibliog., index of personal names This joint publication is the conclusion of many years of research by the authors into the history of Protestantism in the Cuiavian-Pomeranian region – one of the most important territories for the development of Protestantism (both Lutheranism and Calvinism) in the history of the Polish-Lithuanian Com- monwealth – but it also contains a number of new insights and conclusions by the experts involved in its compilation. Signifi cantly, it was published shortly after the quincentenary of the Reformation in Poland. It is an anthology of thirteen articles, prefaced with an introduction by the editor of the volume, Jarosław Kłaczkow. The articles can be described as short, insightful summaries concerning the history of the Protestant communities in various parts of the region and in various periods, from the sixteenth century and the beginning of the Reformation in the early modern age up to the twentieth century. The book is divided into sections on a geographical basis: Cuiavia (diachronic articles by Marek Romaniuk, Tomasz Łaszkiewicz and Tomasz Krzemiński on the Protestant communities in Bydgoszcz, Inowrocław, and Eastern Cuiavia respectively, and a contribution on the history -

Aleksander Gieysztor and Gerard Labuda. for the 100Th Anniversary of Two Great Historians' Birthdays

Czech-Polish Historical and Pedagogical Journal 50 Aleksander Gieysztor and Gerard Labuda. For the 100th Anniversary of Two Great historians’ Birthdays (1916–2016) Marceli Kosman / e-mail: [email protected] Institut of Political Sciencies, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland Kosman, M. (2016). Aleksander Gieysztor and Gerard Labuda (For the 100th anniversary of two great Historians’ birthdays 1919–2016). Czech-Polish Historical and Pedagogical Journal, 8/2, 50–68. Two Polish historians and friends, both born in 1916, were among the most eminent medievalists in Poland in the 20th century. Their academic debut came in the years preceding the outbreak of WWII, while their careers progressed brilliantly in the years following the end of the war. For several decades, they marked their academic presence as the authors of great works, and they held the most prominent offices in academic life in Poland and in the international arena. They took an active part in the process of political transition, leading to Poland regaining full sovereignty in 1989, and they approved of its evolutionary mode. They were unquestionable moral authorities for scolarly circles and beacons in public activities. Aleksander Gieysztor died in 1999, followed eleven years later by Gerard Labuda (2010), who remained active until his last days. The 100th anniversary of their birthdays reminds historical circles, first and foremost, albeit not only, of Warsaw and Poznań, about their academic and public achievements. Key words: Poland in the second half of the nineteenth century; Medievalism; science and politics; historical culture; political culture I The Gieysztor family came from the Trock region in historical Lithuania. -

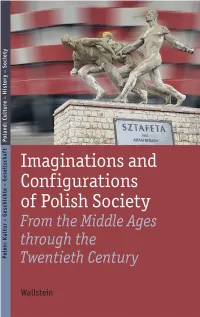

Imaginations and Configurations of Polish Society. from the Middle

Imaginations and Configurations of Polish Society Polen: Kultur – Geschichte – Gesellschaft Poland: Culture – History – Society Herausgegeben von / Edited by Yvonne Kleinmann Band 3 / Volume 3 Imaginations and Configurations of Polish Society From the Middle Ages through the Twentieth Century Edited by Yvonne Kleinmann, Jürgen Heyde, Dietlind Hüchtker, Dobrochna Kałwa, Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Katrin Steffen and Tomasz Wiślicz WALLSTEIN VERLAG Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Deutsch-Polnischen Wissenschafts- stiftung (DPWS) und der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (Emmy Noether- Programm, Geschäftszeichen KL 2201/1-1). Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2017 www.wallstein-verlag.de Vom Verlag gesetzt aus der Garamond und der Frutiger Umschlaggestaltung: Susanne Gerhards, Düsseldorf © SG-Image unter Verwendung einer Fotografie (Y. Kleinmann) von »Staffel«, Nationalstadion Warschau Lithografie: SchwabScantechnik, Göttingen ISBN (Print) 978-3-8353-1904-2 ISBN (E-Book, pdf) 978-3-8353-2999-7 Contents Acknowledgements . IX Note on Transliteration und Geographical Names . X Yvonne Kleinmann Introductory Remarks . XI An Essay on Polish History Moshe Rosman How Polish Is Polish History? . 19 1. Political Rule and Medieval Society in the Polish Lands: An Anthropologically Inspired Revision Jürgen Heyde Introduction to the Medieval Section . 37 Stanisław Rosik The »Baptism of Poland«: Power, Institution and Theology in the Shaping of Monarchy and Society from the Tenth through Twelfth Centuries . 46 Urszula Sowina Spaces of Communication: Patterns in Polish Towns at the Turn of the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times . 54 Iurii Zazuliak Ius Ruthenicale in Late Medieval Galicia: Critical Reconsiderations . -

Alexandro Gieysztor Homini-Civi Polono-Viro Doctissimo-Professori Praestantissimo in Memoriam Professor Aleksander Gieysztor (1916-1999)

ORGANON 32:2003 Jan Malicki (Warsaw, Poland) ALEXANDRO GIEYSZTOR HOMINI - CIVI POLONO - VIRO DOCTISSIMO - PROFESSORI PRAESTANTISSIMO IN MEMORIAM PROFESSOR ALEKSANDER GIEYSZTOR (1916-1999) A MAN - A POLE - A HUMANIST - A SCHOLAR Alexander Gieysztor* natus est die XVII mensis Julii a. MCMXVI, obiit die IX m. Februarii anni MCMXCIX, quae sunt vitae limina unius ex virorum Polonorum doctissimorum saeculi vicesimi. De cuius vitae momentis singula- ribus, de origine familiari, de investigationibus, de fascinationibus, de illius scientia atque doctrina, de positione in virorum doctorum vita intemationali adepta, deinde de illius civis Poloni atque militis in saeculo vicesimo Poloniae et Europae terribili atque turbulento breviter elucubratione in nostra narra- bimus, ut memoriae mandemus. Non minimi momenti est quinto post obitum anno illius Professoris reminisci aliquem, qui de illo non aliter dicere possit, quam «O, non obliviscende Magister!» Hunc textum iam hodierna lingua intemationali continuare constituimus, dum veremur, ne, etsi mori orationum in memoriam conscriptarum tradito ge- ramus, eorum, qui commemorationes nostras lecturi sint, coetus nimis commi- nuatur, quod vitandum esse putamus. Aleksander Gieysztor*, one of the greatest Polish 20th century scholars and humanists was born on 17 July 1916 and died on 9 February 1999. This remembrance article briefly outlines some of the elements of his biography, family roots, his scientific research, fascinations and achievements, his inter national position as well as his life as a Polish citizen and as a soldier in the 20th century, which was such a turbulent time for both Poland and Europe. The fact that this article on the fifth anniversary of the Professor’s death has been written by someone who has until now not been able to call him otherwise than «Unforgettable Master!» is probably of some importance, too. -

Constructing Community In

Miraslau Shpakau THE ROMAN MYTH: CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY LITHUANIA MA Thesis in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Central European University Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2016 THE ROMAN MYTH: CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY IN SIXTEENTH- CENTURY LITHUANIA by Miraslau Shpakau (Belarus) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2016 THE ROMAN MYTH: CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY IN SIXTEENTH- CENTURY LITHUANIA by Miraslau Shpakau (Belarus) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2016 THE ROMAN MYTH: CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY IN SIXTEENTH- CENTURY LITHUANIA by Miraslau Shpakau (Belarus) Thesis submitted -

Melting Puzzle RIENTALIS O UROPAE E IBLIOTHECA XLIX Studia 7 B U K O W a E • N • O W a W R T

Melting Puzzle B IBLIOTHECA EUROPAE ORIENTALIS XLIX studia 7 U K O W A E • N • O W A W R T S S Z Y A Z W E R A S K W I E O T • • Warsaw Scientific Society Societas Scientiarum Varsaviensis Leszek Zasztowt MELTING PUZZLE THE NOBILITY, SOCIETY, EDUCATION AND SCHOLARLY LIFE IN EAST-CENTRAL EUROPE (1800s-1900s) WARSAW 2018 Finananced by The Józef Mianowski Fund – A Foundation for the Promotion of Science: Jadwiga June Kruszewski Fund The University of Texas at El Paso (The Kruszewski Family Foundation) Translation and English editors: Tristan Korecki and Bolesław Jaworski Technical editing: Dorota Kozłowska Index compiled: Dorota Kozłowska Cover and cover pages design by: Jan Jerzy Malicki (based on the BEO series design by Maryna Wiśniewska) Typesetting: OFI, Warszawa Front cover illustrations: Dariusz Grajek, Szlachciury (Petty nobles), oil on canvas, 2016 Tomasz Makowski, The Radziwill’s map of the Great Duchy of Lithuania, 1613. A copy from the Willem Janszoon Blauew’s Appendix Theatri, 1631 (copy of the map from T. Niewodniczański Collection, deposit at the Royal Castle in Warsaw - Museum, sign. TN 1141) © Copyright by Leszek Zasztowt © Copyright by Centre for East European Studies, University of Warsaw, Warsaw 2018 © Copyright by Oficyna Wydawnicza ASPRA-JR, Warszawa 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Centre for East European Studies, University of Warsaw Published by: Studium Europy Wschodniej Oficyna Wydawnicza ASPRA-JR Uniwersytet Warszawski 03-982 Warszawa, Dedala 8/44 Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28 phone 602 247 367, fax 22 870 03 60 00-927 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected] www.studium.uw.edu.pl www.aspra.pl ISBN 978-83-61325-63-5 ISBN 978-83-7545-816-9 23,5 ark.