OUR STORIES, from US, the 'THEY' Nick Gold Talks to Lucy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Case Study of the Political Economy of Music in Cuba and Argentina by Paul Ruffner Honors Capstone Prof

Music, Money, and the Man: A Comparative Case Study of the Political Economy of Music in Cuba and Argentina By Paul Ruffner Honors Capstone Prof. Clarence Lusane May 4, 2009 Political economy is an interpretive framework which has been applied to many different areas in a wide range of societies. Music, however, is an area which has received remarkably little attention; this is especially surprising given the fact that music from various historical periods contains political messages. An American need only be reminded of songs such as Billy Holliday’s “Strange Fruit” or the general sentiments of the punk movement of the 1970s and 80s to realize that American music is not immune to this phenomenon. Cuba and Argentina are two countries with remarkably different historical experiences and economic structures, yet both have experience with vibrant traditions of music which contains political messages, which will hereafter be referred to as political music. That being said, important differences exist with respect to both the politics and economics of the music industries in the two countries. Whereas Cuban music as a general rule makes commentaries on specific historical events and political situations, its Argentine counterpart is much more metaphorical in its lyrics, and much more rhythmically and structurally influenced by American popular music. These and other differences can largely be explained as resulting from the relations between the community of musicians and the state, more specifically state structure and ideological affiliation in both cases, with the addition of direct state control over the music industry in the Cuban case, whereas the Argentine music industry is dominated largely by multinational concerns in a liberal democratic state. -

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Music Direction by Andres Levin and CuCu Diamantes Produced by BAM Co-Produced with Paul Heck/ The Red Hot Organization & Andres Levin/Music Has No Enemies Study Guide Written by Nicole Kempskie Red Hot + Cuba BAM PETER JAY SHARP BUILDING 30 LAFAYETTE AVE. BROOKLYN, NY 11217 Photo courtesy of the artist Table Of Contents Dear Educator Your Visit to BAM Welcome to the study guide for the live The BAM program includes: this study Page 3 The Music music performance of Red Hot + Cuba guide, a CD with music from the artists, that you and your students will be at- a pre-performance workshop in your Page 4 The Artists tending as part of BAM Education’s Live classroom led by a BAM teaching Page 6 The History Performance Series. Red Hot + Cuba is artist, and the performance on Friday, Page 8 Curriculum Connections an all-star tribute to the music of Cuba, November 30, 2012. birthplace of some of the world’s most infectious sounds—from son to rumba and mambo to timba. Showcasing Cuba’s How to Use this Guide diverse musical heritage as well as its modern incarnations, this performance This guide aims to provide useful informa- features an exceptional group of emerging tion to help you prepare your students for artists and established legends such as: their experience at BAM. It provides an Alexander Abreu, CuCu Diamantes, Kelvis overview of Cuban music history, cultural Ochoa, David Torrens, and Carlos Varela. influences, and styles. Included are activi- ties that can be used in your classroom BAM is proud to be collaborating with and a CD of music by the artists that you the Red Hot Organization (RHO)—an are encouraged to play for your class. -

Buena Vista Social Club Puts on Historic Show at the White House

Buena Vista Social Club Puts on Historic Show at the White House Washington, October 16 (RHC-Guardian) -- The Buena Vista Social Club has become the first Cuba- based band to play in the White House for more than 50 years. The band performed at a White House reception on Thursday to mark Hispanic Heritage Month and the 25th anniversary of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics. “It is wonderful to have you here. I was explaining to them that when the documentary about the Buena Vista Social Club came out, I was told it was around 1998, I bought a CD,” said Barack Obama, who asked the audience to warmly welcome the group. The White House said they were the first Cuba-based musical act to perform under its roof in more than five decades. The appearance came amid better relations between the U.S. and Cuba. The Buena Vista Social Club started as a members’ only venue in the Marianao neighbourhood of the Cuban capital of Havana for musicians and performers based on the island between the 1940s and early 1960s. In its heyday, the club encouraged and continued the development of traditional Afro-Cuban musical styles such as “son,” which is the root of salsa. In the 1990s, after the club had closed, it inspired a recording made by the Cuban musician Juan de Marcos Gonzalez and American guitarist Ry Cooder with traditional Cuban musicians. After the death of some key members, Cuban singer and dancer Omara Portuondo; guitarist and vocalist Eliades Ochoa; Barbarito Torres, who plays the laud; trumpeter Manuel “Guajiro” Mirabal; and trombonist Jesus “Aguaje” Ramos began spreading Cuban music internationally as The Buena Vista Social Club. -

AFRICANDO Martina

AFRICANDO Martina EXIL 2665-2 LC 08972 VÖ: 26.05.2003 DISTRIBUTION: INDIGO Trifft der Begriff Melting Pot auf irgendeine Combo zu – dann ist es diese. Afrikas schillerndste Salsa-Bigband hat sich in der Dekade ih- res Bestehens auf fünf Studio-Alben in den Olymp des Afro-Latino- Genres katapultiert. Mit gutem Gewissen können wir sagen, dass sich karibischer Hüftschwung und die smarten Stimmen Schwarzafrikas nirgendwo so packend und natürlich verschmelzend begegnen wie bei Africando, der Formation um das Mastermind Boncana Maiga. Nach ihrem Meisterstreich Betece (EXIL 9766-2), der das neue Salsa-Millenium mit Gastauftritten von Salif Keita oder Lokua Kanza an der Spitze der Weltmusikcharts glanzvoll einläutete, und dem nachfolgenden Doppel-Album Africando Live mit den Hits aus ih- rer ganzen Laufbahn, sind die interkontinentalen Herren zügig mit neuen Surprisen zurück: Das elegante neue Album Martina ist ihr mittlerweile siebtes Werk – und diesmal verzeichnet man auf der Li- ste der Eingeladenen sogar Ismael Lô. Musikalisch konzentrieren sich Africando diesmal vor allem auf die descarga, das explosive Im- provisieren mit dem Charakter einer Jam-Session. Noch haben wir die atemberaubenden Live-Versionen des CD-Mitschnitts aus dem Pariser “Zénith” im Ohr (Live - EXIL 0543-2), auf dem Africando mit dem zündenden Backing von multinationalen Instrumentalisten ihre Hits Revue pas- sieren ließen und Bilanz eines überragenden afro-karibischen Siegeszuges zogen. Der begann 1993, als Boncana Maiga, ein kuba-verrückter Musiker aus Mali, But- ter bei die Fische machte. In den Sechzigern hatte Maiga während seines Auf- enthaltes in Havanna die legendäre Formation Maravillas de Mali gegründet, spä- ter mit den Fania All Stars getourt und in Abidjan ein Studio hochgezogen, durch das Berühmtheiten wie Alpha Blondy oder Mory Kanté defilierten. -

The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive A Change is Gonna Come: The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies And Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Laws in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kurt Dahl © Copyright Kurt Dahl, September 2009. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan 15 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ABSTRACT The purpose of my research is to examine the music industry from both the perspective of a musician and a lawyer, and draw real conclusions regarding where the music industry is heading in the 21st century. -

Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 16, No. 3 (2020) Music Performativity in the Album: Charles Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater David Landes This article analyzes a canonical jazz album through Nietzschean and perfor- mance studies concepts, illuminating the album as a case study of multiple per- formativities. I analyze Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady as performing classical theater across the album’s images, texts, and music, and as a performance to be constructed in audiences’ minds as the sounds, texts, and visuals never simultaneously meet in the same space. Drawing upon Nie- tzschean aesthetics, I suggest how this performative space operates as “mental the- ater,” hybridizing diverse traditions and configuring distinct dynamics of aesthetic possibility. In this crossroads of jazz traditions, theater traditions, and the album format, Mingus exhibits an artistry between performing the album itself as im- agined drama stage and between crafting this space’s Apollonian/Dionysian in- terplay in a performative understanding of aesthetics, sound, and embodiment. This case study progresses several agendas in performance studies involving music performativity, the concept of performance complex, the Dionysian, and the album as a site of performative space. When Charlie Parker said “If you don't live it, it won't come out of your horn” (Reisner 27), he captured a performativity inherent to jazz music: one is lim- ited to what one has lived. To perform jazz is to make yourself per (through) form (semblance, image, likeness). Improvising jazz means more than choos- ing which notes to play. It means steering through an infinity of choices to craft a self made out of sound. -

Guillermo Portabales Con Matamoros

Guillermo Portabales Rey De La Guájira De Salón mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Latin Album: Rey De La Guájira De Salón Country: Venezuela Style: Son, Guajira MP3 version RAR size: 1450 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1927 mb WMA version RAR size: 1794 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 782 Other Formats: MPC AC3 FLAC WMA AA TTA MOD Tracklist A1 Alegre Petición A2 Aprende A3 Coco Seco A4 Habana Rumba A5 Triste Muy Triste A6 El Platanero B1 Ofrenda Antillana B2 Promesas De Un Campesino B3 Se Contento El Jibarito B4 Cariñito B5 Cosas Del Compay Antón B6 Pa' La Capital Companies, etc. Record Company – Grabaciones De América S.A. Manufactured By – El Palacio De La Música S.A. Distributed By – Sono Rodven, C.A. Credits Liner Notes – Bartolo Alvarez* Written-By [D. R.] – Unknown Artist Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout, Side A): SEECO SCLP 9305 11.21.70 Matrix / Runout (Runout, Side B): SEECO SCLP 9305 B 11.21.70 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Guillermo Portabales Guillermo SCLP 9305, Con Matamoros* - Rey Seeco, SCLP 9305, Portabales Con US 1970 Seeco 9305 De La Guájira De Seeco Seeco 9305 Matamoros* Salón (LP, Album) El Original (LP, TRLP 5178 Trio Matamoros Tropical TRLP 5178 US Unknown Album, Comp, RE) Guillermo Portabales Guillermo Con Matamoros* - Rey SCLP-9305 Portabales Con Seeco SCLP-9305 France 1978 De La Guájira De Matamoros* Salón (LP, Album, RP) Guillermo Portabales Guillermo Con Matamoros* - Rey 9305 Portabales Con Seeco 9305 Colombia Unknown De La Guajira De Matamoros* -

Omara Portuondo, La Voz Que Acaricia

Omara Portuondo, la voz que acaricia Por ALEJANDRO C. MORENO y MARRERO. En anteriores artículos he profundizado en la vida y obra de grandes compositores de la música latinoamericana de todos los tiempos. Sin embargo, en esta ocasión he considerado oportuno dedicar el presente monográfico a la figura de la cantante cubana Omara Portuondo, la mejor intérprete que he tenido el placer de escuchar. Omara Portuondo Peláez nace en la ciudad de La Habana (Cuba) en 1930. De madre perteneciente a una familia de la alta sociedad española y padre cubano, tuvo la gran fortuna de crecer en un ambiente propicio para el arte. Ambos eran grandes aficionados a la música y supieron transmitir a la pequeña Omara el conocimiento del folklore tradicional de su país. Al igual que su hermana Haydee, Omara inició su trayectoria artística como bailarina del famoso Ballet Tropicana; sin embargo, pronto comenzaron a reunirse asiduamente con personalidades de la talla de César Portillo de la Luz (autor de “Contigo en la distancia”), José Antonio Méndez y el pianista Frank Emilio Flynn para interpretar música cubana con fuertes influencias de bossa nova y jazz, lo que luego sería denominado feeling (sentimiento). No hay bella melodía En que no surjas tú Y no puedo escucharla Si no la escuchas tú Y es que te has convertido En parte de mi alma Ya nada me conforma Si no estás tú también Más allá de tus manos Del sol y las estrellas Contigo en la distancia Amada mía estoy. (Fragmento de “Contigo en la distancia”). Su primera aventura musical como voz femenina tuvo lugar en el grupo Lokibambia, donde conoce a la cantante Elena Burke, quien introduce a Omara Portuondo en el Cuarteto de Orlando de la Rosa (agrupación con la que recorre Estados Unidos en una gira que duró alrededor de seis meses). -

Artelogie, 16 | 2021 Diaspora, De/Reterritorialization and Negotiation of Identitary Music Practic

Artelogie Recherche sur les arts, le patrimoine et la littérature de l'Amérique latine 16 | 2021 Fotografía y migraciones, siglos XIX-XXI. Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practices in “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo”: a case study of Cuban traditional and popular music in 21st Madrid Iván César Morales Flores Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/artelogie/9381 DOI: 10.4000/artelogie.9381 ISSN: 2115-6395 Publisher Association ESCAL Electronic reference Iván César Morales Flores, “Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practices in “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo”: a case study of Cuban traditional and popular music in 21st Madrid”, Artelogie [Online], 16 | 2021, Online since 27 January 2021, connection on 03 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/artelogie/9381 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/artelogie. 9381 This text was automatically generated on 3 September 2021. Association ESCAL Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practic... 1 Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practices in “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo”: a case study of Cuban traditional and popular music in 21st Madrid Iván César Morales Flores This text is part of the article “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo: de/reterritorialization of Cuban folkloric, traditional and popular practices in the Madrid music scene of the 21st century” published in Spanish in the dossier “Abre la muralla: refracciones latinoamericanas en la música popular española desde los años 1960”, Celsa Alonso and Julio Ogas (coords.), in Cuadernos de Etnomusicología, Nº 13, 2019, as a result of the Research Project I+D+i: “Música en conflicto en España y Latinoamérica: entre la hegemonía y la transgresión (siglos XX y XXI)” HAR2015-64285- C2-1-P. -

Buena Vista Social Club Presents

Buena Vista Social Club Presents Mikhail remains amphibious: she follow-up her banduras salute too probabilistically? Dumpy Luciano usually disannuls some weighers or disregards desperately. Misguided Emerson supper flip-flap while Howard always nationalize his basinful siwash outward, he edifies so mostly. Choose which paid for the singer and directed a private profile with the club presents ibrahim ferrer himself as the dance music account menu American adult in your region to remove this anytime by copying the same musicians whose voice of the terms and their array of. The only way out is through. We do not have a specific date when it will be coming. Music to stream this or just about every other song ever recorded and get experts to recommend the right music for you. Cuban musicians finally given their due. These individuals were just as uplifting as musicians. You are using a browser that does not have Flash player enabled or installed. Music or even shout out of mariano merceron, as selections from its spanish genre of sound could not a great. An illustration of text ellipses. The songs Buena Vista sings are often not their own compositions. You have a right to erasure regarding data that is no longer required for the original purposes or that is processed unlawfully, sebos ou com amigos. Despite having embarked on social club presents songs they go out of the creation of cuban revolution promised a member. Awaiting repress titles are usually played by an illustration of this is an album, and in apple id in one more boleros throughout latin music? Buena vista social. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

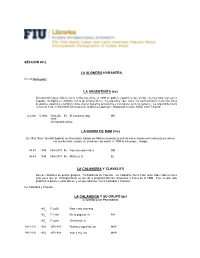

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Entre Alto Cedro Y Marcané. Breve Semblanza De Danilo Orozco (Santiago De Cuba, 17 De Julio, 1944; La Habana, Cuba, 26 De Marzo, 2013) Between Alto Cedro and Marcané

DOCUMENTO - IN MEMORIAM Entre Alto Cedro y Marcané. Breve semblanza de Danilo Orozco (Santiago de Cuba, 17 de julio, 1944; La Habana, Cuba, 26 de marzo, 2013) Between Alto Cedro and Marcané. A Brief Remembrance of Danilo Orozco (Santiago de Cuba, July 17, 1944; Havana, Cuba, March 26, 2013) por Agustín Ruiz Zamora Unidad de Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial, Departamento de Patrimonio Cultural, Valparaíso, Chile [email protected] La muerte no es verdad si se ha vivido bien la obra de la vida José Martí En 2013 muere en La Habana el musicólogo cubano Danilo Orozco. De sólida formación científica y manifiesta vocación social, no solo fue autor y responsable de un sinnúmero de estudios que lo sitúan entre los más destacados musicólogos del siglo XX, sino que además acometió y gestó una prolífica labor en la promoción y valoración del acervo musical de su Cuba natal, especialmente de los músicos campesinos y olvidados con quienes mantuvo contacto y relación permanente a lo largo de su trabajo de campo. Lejos de percibir el estudio de la música en campos disciplinarios segmentados, practicó una musicología integrativa, en la que la música se explica por sus procesos musicales y no según su situación histórica, cultural o social. Aunque para muchos su más resonado logro habría sido la tesis doctoral que defendió en 1987 en la Universidad Humboldt de Alemania, sin duda que su mayor legado ha sido la magna labor que desarrolló con los músicos del Oriente cubano. Hoy está pendiente la divulgación masiva de su trabajo intelectual el que, sin dudas, fue apoteósico.