Population Transition Selected Papers of Bhopal Seminar 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Answered On:02.12.2002 Discovery of Ancient Site by Asi Chandra Vijay Singh

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM AND CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2136 ANSWERED ON:02.12.2002 DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT SITE BY ASI CHANDRA VIJAY SINGH Will the Minister of TOURISM AND CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) names of the monuments in the Moradabad and Bareilly division under ASI; (b) whether Excavations conducted at Madarpur in Moradabad District of Uttar Pradesh have unearthed an archaeological site dating to 2nd century B.C.; (c) steps taken for preservation of the site and the amount allocated for the purpose; and (d) steps proposed to be taken to further explore to excavate the area? Answer MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND CULTURE (SHRI JAGMOHAN ) (a) A list of Centrally protected monuments in Moradabad and Bareilly division is annexed. (b) The excavation conducted in January, 2000 revealed findings datable to 2nd millennium B.C. (c) & (d) Steps have been taken to conserve the site. An amount of Rs.1,84,093/- has been incurred so far. Further steps have been initiated to explore adjacent areas to assess its archaeological potentiality. ANNEXURE ANNEXURE REFFERED TO IN REPLY OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2136 TO BE ANSWERED ON 2.12.2002 REGARDING DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT SITE BY ASI (a) Moradabad Division (i) Moradabad District: S.No. Locality Name of the Centrally Protected Monument/Site 1. Alipur, Tehsil :Chandausi Amarpati Khera 2. Alipur, Tehsil:Chandausi Chandesvara Khera 3. Berni, Tehsil;Chandausi Khera or Mound reputed to be the ruin or palace or Raja Vena 4. Bherabharatpur, Tehsil Amorha Large mound, the site of an ancient temple 5. -

Division Railway Bsnl/Mtnl Location

EMERGENCY / COMML. CONTROL PHONE Nos.TO BE ACTIVATED IN CASE OF DISASTER/ACCIDENT OF NORTHERN RAILW AY DIVISION RAILWAY BSNL/MTNL LOCATION DELHI Railway Board 030-43859 011-23388230 Emergency/ 030-43600 011-23388503 punctuality control 030-43528 .... Room No. 476 P 030-43399 011-23382638 Safty cell,Room No.476 K Baroda House 030-32215 011-23384605 Emergency control 030-32268 011-23385106 ---------do--------- .... 011-23387635 ---------do--------- 030-32923 011-23381174 Commertial Control 030-32924 011-23384040 ---------do--------- Control office NDLS 030-22233 011-23366543 Conference Room. 030-26240 011-23341376 ---------do--------- 030-22427 011-23740024 Commertial Control 030-23491 011-23745466 ---------do--------- New Delhi Rly.Stn. 030-22280 011-23742292 Dy.SS/Comml./Office 030-22623 -- ---------do--------- Old Delhi Rly.Stn. 030-77201 011-23962389 ---------do--------- Hazrat Nizamuddin 030-72389 011-24359748 May I help you booth FIROZPUR Firozpur 031-22107 01632-244327 Control Conference 031-22177 01632-244154 Room Jalandhar 031-32802 0181-2456240 Stn.Supdtt.Office. 031-33440 0181-2225615 ---------do--------- Ludhiana 031-52802 0161-2441361 ---------do--------- -- 0161-2744702 ---------do--------- Amritsar 031-73700 0183-2225087 Dy.SSupdtt.Office. 031-72810 0183-2560824 ---------do--------- Pathankot 031-62810 0186-2254867 ---------do--------- 031-63435 0186-2220035 ---------do--------- Jammu Tawi 031-42802 0191-2474757 ---------do--------- 031-42882 0191-2470116 ---------do--------- LUCKNOW Lucknow 032-23532 0522-2234525 Control office Hazrat -ganj. EMERGENCY / COMML. CONTROL PHONE Nos.TO BE ACTIVATED IN CASE OF DISASTER/ACCIDENT OF NORTHERN RAILWAY DIVISION RAILWAY BSNL/MTNL LOCATION 032-23533 0522-2234525 -ganj. 032-23246 0522-2234537 Commertial control. 032-23244 0522-2234533 -----------do---------- Varanasi 032-062-204 0542-2342511 Stn.Supdtt.Varanasi Faizabad ... -

Report of the Regional Workshop to Share, Learn and Plan with Quality and Sustainability of Swachh Bharat Mission (G)

Report of the Regional workshop to share, learn and plan with quality and sustainability of Swachh Bharat Mission (G) 1 Report and Proceedings of a regional workshop on Rapid Action Learning, sharing and planning with quality and sustainability of Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) Duration- 11th to 13th September, 2017 Objective- Achieving District-Wide Quality and Sustainability with the SBM-G Across Uttar Pradesh Organised by - Divisional Swachh Bharat Team, Moradabad In collaboration, with Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) & CLTS Knowledge Hub at Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, UK 2 Table of Contents Subject Page 1. Introduction -------------------------------------------------04 2. Background & Context-------------------------------------04 3. Objectives of the workshop-------------------------------05 4. Process & Methodology-----------------------------------05 5. Selected practical action----------------------------------06 6. Feedback from participants------------------------------08 7. Key learnings------------------------------------------------09 8. Follow-up and way forward------------------------------10 9. Annexure 01 – Selected Practical Actions shared 10. Annexure 02 – Guidance notes for convening 11. Annexure 03- Feedback from the participants 12. Annexure 04 –Note on Quality and Sustainability 13. Annexure 05 – Schedule of the Workshop 14. Annexure 06 – List of participants 15. Annexure 07- Photo Gallery 3 Introduction This Regional Workshop to share, learn and plan with quality -

![" *!' Trdvd, ERS]Zxyzd F Uvc ]V D 0DUND] FOHDUHG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7407/trdvd-ers-zxyzd-f-uvc-v-d-0dund-fohduhg-1127407.webp)

" *!' Trdvd, ERS]Zxyzd F Uvc ]V D 0DUND] FOHDUHG

) 0&+1 % !. !% !. VRGR $"#(!#1')VCEBRS WWT!Pa!RT%&!$"#1$# $(")$!*+, ,01-1,-2 +,-./ !0,3 4 1 ! ( *(*(2 *&&* 3"4 7( 1?*&1?( ,, &O, +(,- ,78 ? @-?1, @-7@(* +(1(+(8( &- 4"56'1& 1,7/( )&8-(* *8-(+7,(+ ? B7( 8- 17 8-+/- +(-+7 -3+(@+ AB3+ , 8 %&49: $$' ;< - . ././0 ,1 = * ( ( +(,- admitted to isolation wards in various States in the country n its biggest spike till date, following the disclosure that IIndia over the past 24 hours they had attended the Tablighi till Wednesday night recorded conference. A total of 16 States 386 new cases of coronavirus have been searching for taking the tally to 1,906 with Tablighi members. the Government blaming the According reports, at least spurt in cases on the travel by 200 from Karnataka, 140 from members of Tablighi Jamaat Andhra Pradesh and 45 from and asserted that it was not a Telangana have been identi- national trend. fied. The total number of “The number of positive those who attended the con- cases has gone up since ference varies from State to Tuesday. One of main reasons State with Maharashtra listing for it is travel by members of 185 and Karnataka estimating Tablighi. This is not a nation- 342 to have participated in the al trend,” said Lav Agarwal, meeting. Joint Secretary in the Union With the Tabligh incident Ministry of Health. spiking the coronavirus num- According to Ministry’s bers in the country, Prime website, the total number of Minister Narendra Modi spoke active COVID-19 cases to Maharashtra Chief Minister reached 1,637 in India by and asked the State to trace out Wednesday noon, whereas the & P the missing Jamaat members death toll has risen to 42 from "#$%&'() * .% who attended the Delhi con- 32 recorded on Tuesday. -

Project Summary

Project Summary Proposed Protected forest land to be diverted for Doubling of Railway Track from (Km No.- 0.00 to 80.30) Roza to Sitapur Railway {KM No.- 0.00 – 11.00 in Shahjahanpur district}, {KM No.- 11.00 to 28.00 & 34.00 to 46.00 in Lakhimpur Kheri district}, {KM No.- 28.00 to 34.00 in Hardoi district} and {KM No.- 46.00 to 80.30 in Sitapur district} in Northern Railway Division Moradabad. District wise details of forest land and non forest land are as follows: Sr. No. DISTRICT PROTECTED NON FOREST FOREST LAND LAND Area (in Ha) Area (in Ha) 1 Shahjahanpur 8.80 0.0175 2 Lakhimpur Kheri 24.06 0.3235 3 Hardoi 6.1133 0.0851 4 Sitapur 30.6259 0.6435 Total Area 69.5992 1.0696 Mahesh Chand Executive Engineer/Con Northern Railway,Moradabad Area Calculation Sheet Proposed Protected Forest Land to be Diverted For Proposed new 2nd line along with existing Railway line under Roza - Sitapur Railway Track (Km. no. 0.00 - 80.30) Doubling Project of Northern Railway, from Km. 0.00 to 11.00, in Moradabad Division, District: Shahjahanpur (Uttar Pradesh) Protected Forest Land Area Calculation From To Length Width Area Area Sr. No. (Km) (Km) (m) (m) (SqM) (Ha) 1 1.900 7.360 5460.00 8.00 43680.00 4.3680 2 8.670 11.000 2330.00 8.00 18640.00 1.8640 7790.00 62320.00 6.2320 Proposed Protected Forest Land Area 6.2320Ha Protected Forest Land along Railway Yards Forest Land Area Calculation From To Length Width Area Area Sr. -

Prefrenceformat Upcircle190718.Pdf

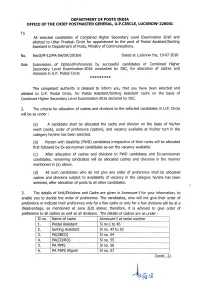

DEPARTMENT OF POSTS INDIA oFFICE OF THE CHIEF POSTMASTER GENERAL, U.P.CIRCLE, LUCKNOW-226OOL All selected candidates of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination 2016 and allotted to Uttar Pradesh Circle for appointment to the post of Postal Assistant/Softing Assistant in Department of Posts, Ministry of Communications. No. RecttiM-12/PA-SA/DR/20L816 Dated at Lucknow the, 19-07-2018 Sub: Submission. of Option/Preferences by successful candidates of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination-2016 conducted by SSC, for allocation of cadres and divisions in U.P. Postal Circle ********* The competent authority is pleased to inform you, that you have been selected and allotted to U.P. Postal Circle, for Postal Assistant/Sorting Assistant cadre on the basis of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination-2016 declared by SSC. 2. The criteria for allocation of cadres and divisions to the selbcted candidates in U.P. Circle will be as under : (a) A candidate shall be allocated the cadre and division on the basis of his/her merit (rank), order of preference (option), and vacanry available at his/her turn in the category he/she has been selected. (b) Person with disability (PWD) candidates irrespective of their ranks will be allocated first followed by Ex-seruiceman candidates as per the vacancy available. (c) After allocation of cadres and divisions to PWD candidates and Ex-seruiceman candidates, remaining candidates will be allocated cadres and divisions in the manner mentioned in (a) above. (d) All such candidates who do not give any order of preference shall be allocated cadres and divisions subject to availability of vacanry in the category he/she has been selected, after allocation of posts to all other candidates. -

Navigate in India

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-2, Issue-4, April 2013 Navigate In India B. Veeramallu, M.Aparna Abstract-Indian Railways is one of the world's largest railway III. PROBLEMS IN THE EXISTING SYSTEM networks comprising 115,000 km (71,000 mi) of track over a route of 65,000 km (40,000 mi) and 7,500 stations. IR carries When a user selects connecting trains, he should know about about 7,500 million passengers annually or more than 20 million the path or the route in which the train travels, which would passengers daily (more than a half of which are suburban not be possible all the time. Even if the user knows one of passengers) and 2.8 million tons of freight daily. the major stops like junction stations, it is not always Railways are divided into Zones Indian railways has 17 zones possible to find out a connecting train from that point at that (SC, WCR, WR, NFR...). Zones are divided into divisions instance of time. So the user has to find out the connecting [Vijayawada division, Bhopal division Varanasi division, points and then search for the trains from that point to the Moradabad division, Lucknow division etc.] Divisions are headed destination; and even the user has to synchronize the timings by a DRM [Divisional Railway Manager]. with previous train timing. This is a very time consuming Under DRM each department has one officer as in-charge for maintenance of their equipment. Indian Railways has 68 process and so is not user-friendly. -

NORTHERN RAILWAY ASSETS-ACQUISITION, CONSTRUCTION and REPLACEMENT for 2014-15 (Figures in Thousand of Rupees) Item Particulars Allocation RE 2014-15 No

3.1.1 NORTHERN RAILWAY ASSETS-ACQUISITION, CONSTRUCTION AND REPLACEMENT FOR 2014-15 (Figures in thousand of Rupees) Item Particulars Allocation RE 2014-15 No. NEW LINES (CONSTRUCTION) A - Works in Progress 1 Nangal Dam-Talwara (83.74 km) - New broad gauge line & taking over siding Cap. 30,00,16 Mukerian-Talwara (29.16 km) 2 Abohar-Fazilka (42.717 km) Cap. 1,00,00 3 Tarantaran-Goindwal (21.5 km) Cap. 30,00 4 Chandigarh-Ludhiana (112 km) Cap. 20,25,00 EBR 5,00,00 5 Rewari-Rohtak (81.26 km) incl. new material modification for shifting of Rohtak - Cap. 12,00,00 Gohana - Panipat through bypass line EBR 20,00,00 6 Jind-Sonepat (88.9 km) Cap. 117,49,78 EBR 45,00,00 7 Jawarhar Lal Nehru Port-Tughlakabad-Dadri via Ahmedabad & Palanpur - Dedicated Cap. 764,00,00 multimodal high axle load freight corridor - Land acquisition 8 Dankuni - Ludhiana - Dedicated multimodal high axle load freight corridor - Land Cap. 286,00,00 acquisition 9 Chandigarh-Baddi (33.23 km) Cap. 13,00 EBR 2,00,00 10 Deoband (Muzaffarnagar)-Roorkee (27.45 km) Cap. 1,00,00 EBR 5,00,00 11 Bhanupalli-Bilaspur-Beri (63.1 km) Cap. 2,00,00 EBR 5,00,00 12 Rishikesh-Karnaprayag (125.09 km) Cap. 20,00,00 13 Qadian-Beas (39.68 km) Cap. 1 14 Unchahar-Amethi (66.17 km) Cap. 56,00 15 Rohtak-Meham-Hansi (68.8 km) Cap. 1,00,00 EBR 10,00,00 16 Delhi - Sohna - Nuh - Firozpur Jhirka - Alwar (104 km) Cap. -

Basic Information of Urban Local Bodies – Uttar Pradesh

BASIC INFORMATION OF URBAN LOCAL BODIES – UTTAR PRADESH As per 2006 As per 2001 Census Election Name of S. Growth Municipality/ Area No. of No. Class House- Total Rate Sex No. of Corporation (Sq. Male Female SC ST (SC+ ST) Women Rate Rate hold Population (1991- Ratio Wards km.) Density Membe rs 2001) Literacy 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 I Saharanpur Division 1 Saharanpur District 1 Saharanpur (NPP) I 25.75 76430 455754 241508 214246 39491 13 39504 21.55 176 99 887 72.31 55 20 2 Deoband (NPP) II 7.90 12174 81641 45511 36130 3515 - 3515 23.31 10334 794 65.20 25 10 3 Gangoh (NPP) II 6.00 7149 53913 29785 24128 3157 - 3157 30.86 8986 810 47.47 25 9 4 Nakur (NPP) III 17.98 3084 20715 10865 9850 2866 - 2866 36.44 1152 907 64.89 25 9 5 Sarsawan (NPP) IV 19.04 2772 16801 9016 7785 2854 26 2880 35.67 882 863 74.91 25 10 6 Rampur Maniharan (NP) III 1.52 3444 24844 13258 11586 5280 - 5280 17.28 16563 874 63.49 15 5 7 Ambehta (NP) IV 1.00 1739 13130 6920 6210 1377 - 1377 27.51 13130 897 51.11 12 4 8 Titron (NP) IV 0.98 1392 10501 5618 4883 2202 - 2202 30.53 10715 869 54.55 11 4 9 Nanauta (NP) IV 4.00 2503 16972 8970 8002 965 - 965 30.62 4243 892 60.68 13 5 10 Behat (NP) IV 1.56 2425 17162 9190 7972 1656 - 1656 17.80 11001 867 60.51 13 5 11 Chilkana Sultanpur (NP) IV 0.37 2380 16115 8615 7500 2237 - 2237 27.42 43554 871 51.74 13 5 86.1 115492 727548 389256 338292 65600 39 65639 23.38 8451 869 67.69 232 28 2 Muzaffarnagar District 12 Muzaffarnagar (NPP) I 12.05 50133 316729 167397 149332 22217 41 22258 27.19 2533 892 72.29 45 16 13 Shamli -

List of Uttar Pradesh Administrative Divisions

List of Uttar Pradesh Administrative Divisions No Divisions Headquarters Districts 1. Agra 2. Firozabad 1 Agra division Agra 3. Mainpuri 4. Mathura 1. Aligarh 2. Etah 2 Aligarh division Aligarh 3. Hathras 4. Kasganj 1. Prayagraj 2. Fatehpur 3 Prayagraj division Prayagraj 3. Kaushambi 4. Pratapgarh 1. Azamgarh 4 Azamgarh division Azamgarh 2. Ballia 3. Mau 1. Badaun 2. Bareilly 5 Bareilly division Bareilly 3. Pilibhit 4. Shahjahanpur 1. Basti 6 Basti division Basti 2. Sant Kabir Nagar 3. Siddharthnagar 1. Banda 2. Chitrakoot 7 Chitrakoot division Chitrakoot 3. Hamirpur 4. Mahoba 1. Bahraich 2. Balarampur 8 Devipatan division Gonda 3. Gonda 4. Shravasti 1. Ambedkar Nagar 2. Barabanki 9 Ayodhya division Ayodhya 3. Ayodhya 4. Sultanpur 5. Amethi 1. Deoria 2. Gorakhpur 10 Gorakhpur division Gorakhpur 3. Kushinagar 4. Maharajganj 1. Jalaun 11 Jhansi division Jhansi 2. Jhansi 3. Lalitpur 1. Auraiya 2. Etawah 3. Farrukhabad 12 Kanpur division Kanpur 4. Kannauj 5. Kanpur Dehat 6. Kanpur Nagar 1. Hardoi 2. Lakhimpur Kheri 3. Lucknow 13 Lucknow division Lucknow 4. Raebareli 5. Sitapur 6. Unnao 1. Baghpat 2. Bulandshahar 3. Gautam Buddha Nagar 14 Meerut division Meerut 4. Ghaziabad 5. Meerut 6. Hapur 1. Mirzapur 15 Mirzapur division Mirzapur 2. Bhadohi 3. Sonbhadra 1. Bijnor 2. Amroha 16 Moradabad division Moradabad 3. Moradabad 4. Rampur 5. Sambhal 1. Muzaffarnagar 17 Saharanpur division Saharanpur 2. Saharanpur 3. Shamli 1. Chandauli 2. Ghazipur 18 Varanasi division Varanasi 3. Jaunpur 4. Varanasi List of Districts in Uttar Pradesh No. Districts -

Railway Network in NCR

Functional Plan on Transport for National Capital Region-2032 4 Railway Network in NCR The railway network in NCR consists of complex rail radials and hubs which have got developed over the last hundred years. It serves the National capital – New Delhi and strives to meet transportation needs of India’s populations, people visiting it for business and social requirements. Unlike other major metros of the country, rail network in the capital also operates as a transit point for passengers and freight volumes moving between Punjab, Haryana, Himachal, J&K, Rajasthan on one side and rest of the country on the other. 4.1 Rail Radials around NCT-Delhi NCT-Delhi is served by the following 8 rail radials: 5 Major Radials i. New Delhi – Faridabad – Palwal (to and from Central India) ii. New Delhi – Sonipat – Panipat (to and from Northern States) iii. New Delhi – Rohtak (to and from parts of Haryana & Punjab) iv. New Delhi – Gurgaon – Rewari – Alwar (to and from Western India) v. New Delhi – Shahdara – Shamli (to and from Western UP) 3 Radials converging at Ghaziabad i. Delhi – Ghaziabad – Khurja – Aligarh (to and from Eastern India) ii. Delhi – Ghaziabad – Hapur – Garhmukteswhwar (to and from UP and Utrakhand iii. Delhi – Ghaziabad – Meerut (to and from Western UP) The following sub sections complete the rail network in NCR and around NCT: i. Delhi – New Delhi – Nizamuddin – Patel Nagar – Delhi Kishanganj – New Delhi/DLI (GAL) ii. Delhi – Shahdara/Sahibabad – Anand Vihar- New Delhi/Delhi (DAL) iii. Khurja – Hapur – Meerut (connecting DLI-Howarh route with DLI-Meerut- Saharanpur and Delhi-Moradabad links) iv. -

Invasive Alien Flora of District Moradabad (U

DIVERSITY, DISTRIBUTION AND USES OF INVASIVE ALIEN ANGIOSPERMS OF RAMPUR DISTRICT (U.P.), INDIA Anupam Pratap Singh1* and Beena Kumari2 1,2 Angiosperms Taxonomy Laboratory Department of Botany, Hindu College, Moradabad, 244001 (U.P.) *Corresponding Author: Anupam Pratap Singh Abstract Invasive alien angiosperms have become an environmental concern in India. A survey of invasive alien angiosperms of Rampur district was made. The data revealed that both aquatic and terrestrial invasive alien angiosperms are becoming threat to the native flora as they reproduce rapidly and crowding out native species. In the present paper 33 invasive alien angiosperms belonging to 23 families are recorded. The contribution of tropical America (70 %) including South America (15 %) is noteworthy. From the interaction with local people and literature survey it was found that invasive alien angiosperms were used as medicine (20), fodder (8), ornamental (8), vegetable (2) and fibre (1). Keywords: Invasive alien angiosperms, Uses, Nativity, Rampur district. I. INTRODUCTION Alien species are non-native or exotic species which introduced either accidentally or deliberately by humans to fulfill their needs. After introduction, they can expand their population and create monospecific thickets. These alien invasive species not only compete for nutrients, moisture and light but for space too. Invasion is usually noticed once the plant has already naturalized. As a result, the introduction of alien species has been recognized as one of the most serious threats to our ecological, social and economic well- being (Cox, 2004; Kohli et al., 2004). About 25 % of the introduced species in India became invasive in a short period of time of 50-100 years (Dogra et al., 2010).