Urban Morphology Moradabad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Answered On:02.12.2002 Discovery of Ancient Site by Asi Chandra Vijay Singh

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM AND CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2136 ANSWERED ON:02.12.2002 DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT SITE BY ASI CHANDRA VIJAY SINGH Will the Minister of TOURISM AND CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) names of the monuments in the Moradabad and Bareilly division under ASI; (b) whether Excavations conducted at Madarpur in Moradabad District of Uttar Pradesh have unearthed an archaeological site dating to 2nd century B.C.; (c) steps taken for preservation of the site and the amount allocated for the purpose; and (d) steps proposed to be taken to further explore to excavate the area? Answer MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND CULTURE (SHRI JAGMOHAN ) (a) A list of Centrally protected monuments in Moradabad and Bareilly division is annexed. (b) The excavation conducted in January, 2000 revealed findings datable to 2nd millennium B.C. (c) & (d) Steps have been taken to conserve the site. An amount of Rs.1,84,093/- has been incurred so far. Further steps have been initiated to explore adjacent areas to assess its archaeological potentiality. ANNEXURE ANNEXURE REFFERED TO IN REPLY OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2136 TO BE ANSWERED ON 2.12.2002 REGARDING DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT SITE BY ASI (a) Moradabad Division (i) Moradabad District: S.No. Locality Name of the Centrally Protected Monument/Site 1. Alipur, Tehsil :Chandausi Amarpati Khera 2. Alipur, Tehsil:Chandausi Chandesvara Khera 3. Berni, Tehsil;Chandausi Khera or Mound reputed to be the ruin or palace or Raja Vena 4. Bherabharatpur, Tehsil Amorha Large mound, the site of an ancient temple 5. -

Govind Swarup

In Memoriam: Govind Swarup rof. Govind Swarup (Figure 1), the at Sydney, Australia, in August 1952. Pdoyen of radio astronomy in India Among other things, he there learnt about and also an internationally acclaimed the dramatic and remarkable discoveries radio astronomer, breathed his last on in the fi eld of radio astronomy being made September 7, 2020, in Pune, India. He by Joseph Pawsey and his group at the is survived by his wife, Mrs. Bina Swa- Radio Physics Division of CSIRO (the rup; their son, Vipin Swarup; and their Australian equivalent of CSIR in India). daughter, Anju Basu. Prof. Swarup was This group was comprised of some of the a legendary fi gure who will be remem- most outstanding experimentalists, such bered in the times to come, not just for as J. Paul Wild, Wilbur N. Christiansen, pioneering radio astronomy in India, but John G. Bolton, and Bernard Y. Mills. also as one who had big ideas and knew Upon his return, Krishnan gave a how to make them real. colloquium at NPL in which he described Figure 1. Govind Swarup these momentous discoveries. That Govind Swarup was born on March (1929–2020). is how Govind got interested in radio 23, 1929, in Thakurdwara, a small town astronomy! Govind was also greatly in the Moradabad district of Uttar Pradesh. His father, Ram enthused by Krishnan’s announcement that he wanted to Raghuvir Saran, established the fi rst theater in Delhi, the start radio astronomy activities at NPL, despite their meager capital of India. His mother, Gunavati Devi, was a housewife resources. -

MATHEMATICAL ASSESSMENT of WATER QUALITY at SAMBHAL, MORADABAD, UTTAR PRADESH (INDIA) ASHUTOSH Dixita, NAVNEET Kumarb and D

Int. J. Chem. Sci.: 10(4), 2012, 2033-2038 ISSN 0972-768X www.sadgurupublications.com MATHEMATICAL ASSESSMENT OF WATER QUALITY AT SAMBHAL, MORADABAD, UTTAR PRADESH (INDIA) ASHUTOSH DIXITa, NAVNEET KUMARb and D. K. SINHA* K.G.K. College, MORADABAD (U.P.) INDIA aSinghania University (Raj.) INDIA bCollege of Engineering, Teerthanker Mahaveer University, MORADABAD (U.P.) INDIA ABSTRACT Underground water samples at ten different water sites of public places were collected and analyzed for different water quality parameters following standard methods of sampling and estimation. The water quality index has been calculated for all the sites using the data of all parameters and WHO drinking water standards. The calculated data reveals that the underground water at Sambhal, Moradabad is severely polluted invariably at all the sites of study. The present study suggests that people exposed to this water are prone to health hazards of polluted drinking water. Key words: Water quality, Water quality index, Unit weight, Quality rating. INTRODUCTION Though water is renewable resource, improper management and reckless use of water systems are causing serious threats to the availability and quality of water1-3. It is the duty of scientists to test the available water in any locality in and around any residential area. As a part of society, it is a must. Attention on water pollution and its management has become a need of hour because of far reaching impact on human health4,5. Moradabad is a ‘B’ class city of western Uttar Pradesh. It is situated at the bank of Ram Ganga river and its altitude from the sea level in about 670 feet. -

Underground Water Quality at Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh

International Journal of Advance Research In Science And Engineering http://www.ijarse.com IJARSE, Vol. No.4, Special Issue (01), February 2015 ISSN-2319-8354(E) UNDERGROUND WATER QUALITY AT SAMBHAL, UTTAR PRADESH, INDIA Navneet Kumar1, Ashutosh Dixit2 1College of Engineering, Teerthanker Mahaveer University, Moradabad, (India) 2IFTM University, Moradabad, (India) ABSTRACT Underground water samples at five different water sites of public places were collected and analyzed for different water quality parameters following standard methods of sampling and estimation. The water quality index has been calculated for all the sites using the data of all parameters and WHO drinking water standards. The calculated data reveals that the underground water at Sambhal, Moradabad is severely polluted invariably at all the sites of study. The present study suggests that people exposed to this water are prone to health hazards of polluted drinking water. Key Words: Water Quality, Water Quality Index, Unit Weight, Quality Rating. I. INTRODUCTION It is the duty of scientists to test the available water in any locality in and around any residential area. As a part of society, it is a must. Attention on water pollution and its management has become a need of hour because of far reaching impact on human health1,5. Sambhal is head quarter of tehsil previously a part of Moradabad district now of Sambhal district itself. It is 38 Km from district Moradabad, 52 Km from Gajraula and about 90 Km from J.P. Nagar. The total area of Sambhal Tehsil is 45 Km2 with total population of more than 3 lacs. It is famous for mentha production and seeng work. -

Division Railway Bsnl/Mtnl Location

EMERGENCY / COMML. CONTROL PHONE Nos.TO BE ACTIVATED IN CASE OF DISASTER/ACCIDENT OF NORTHERN RAILW AY DIVISION RAILWAY BSNL/MTNL LOCATION DELHI Railway Board 030-43859 011-23388230 Emergency/ 030-43600 011-23388503 punctuality control 030-43528 .... Room No. 476 P 030-43399 011-23382638 Safty cell,Room No.476 K Baroda House 030-32215 011-23384605 Emergency control 030-32268 011-23385106 ---------do--------- .... 011-23387635 ---------do--------- 030-32923 011-23381174 Commertial Control 030-32924 011-23384040 ---------do--------- Control office NDLS 030-22233 011-23366543 Conference Room. 030-26240 011-23341376 ---------do--------- 030-22427 011-23740024 Commertial Control 030-23491 011-23745466 ---------do--------- New Delhi Rly.Stn. 030-22280 011-23742292 Dy.SS/Comml./Office 030-22623 -- ---------do--------- Old Delhi Rly.Stn. 030-77201 011-23962389 ---------do--------- Hazrat Nizamuddin 030-72389 011-24359748 May I help you booth FIROZPUR Firozpur 031-22107 01632-244327 Control Conference 031-22177 01632-244154 Room Jalandhar 031-32802 0181-2456240 Stn.Supdtt.Office. 031-33440 0181-2225615 ---------do--------- Ludhiana 031-52802 0161-2441361 ---------do--------- -- 0161-2744702 ---------do--------- Amritsar 031-73700 0183-2225087 Dy.SSupdtt.Office. 031-72810 0183-2560824 ---------do--------- Pathankot 031-62810 0186-2254867 ---------do--------- 031-63435 0186-2220035 ---------do--------- Jammu Tawi 031-42802 0191-2474757 ---------do--------- 031-42882 0191-2470116 ---------do--------- LUCKNOW Lucknow 032-23532 0522-2234525 Control office Hazrat -ganj. EMERGENCY / COMML. CONTROL PHONE Nos.TO BE ACTIVATED IN CASE OF DISASTER/ACCIDENT OF NORTHERN RAILWAY DIVISION RAILWAY BSNL/MTNL LOCATION 032-23533 0522-2234525 -ganj. 032-23246 0522-2234537 Commertial control. 032-23244 0522-2234533 -----------do---------- Varanasi 032-062-204 0542-2342511 Stn.Supdtt.Varanasi Faizabad ... -

Report of the Regional Workshop to Share, Learn and Plan with Quality and Sustainability of Swachh Bharat Mission (G)

Report of the Regional workshop to share, learn and plan with quality and sustainability of Swachh Bharat Mission (G) 1 Report and Proceedings of a regional workshop on Rapid Action Learning, sharing and planning with quality and sustainability of Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) Duration- 11th to 13th September, 2017 Objective- Achieving District-Wide Quality and Sustainability with the SBM-G Across Uttar Pradesh Organised by - Divisional Swachh Bharat Team, Moradabad In collaboration, with Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) & CLTS Knowledge Hub at Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, UK 2 Table of Contents Subject Page 1. Introduction -------------------------------------------------04 2. Background & Context-------------------------------------04 3. Objectives of the workshop-------------------------------05 4. Process & Methodology-----------------------------------05 5. Selected practical action----------------------------------06 6. Feedback from participants------------------------------08 7. Key learnings------------------------------------------------09 8. Follow-up and way forward------------------------------10 9. Annexure 01 – Selected Practical Actions shared 10. Annexure 02 – Guidance notes for convening 11. Annexure 03- Feedback from the participants 12. Annexure 04 –Note on Quality and Sustainability 13. Annexure 05 – Schedule of the Workshop 14. Annexure 06 – List of participants 15. Annexure 07- Photo Gallery 3 Introduction This Regional Workshop to share, learn and plan with quality -

Meerut Development Authority, Meerut

Meerut Development Authority, Meerut Expression of Interest for Consultancy Services and Preparation of Detailed Project Report (DPR) For Rehabilitation and Improvement of Abu Drain in Meerut. Meerut Development Authority invites capable consultants with an expression of interest for preparation of detailed project report for Rehabilitation and Improvement of Abu Drain Meerut. Interested consultants should provide the necessary details in format available on MDA website www.mdameerut.in based on which the consultants will be shortlisted. The submission of EOI document shall be accompanied with processing charge of Rs. 10000/- (Rupees ten thousand only) in the form of a demand draft payable in favour of Vice Chairman, MDA Meerut. Note, the processing charge is non refundable. MDA reserves the right to accept or reject any application without explanation or reason. If the EOI process is cancelled by MDA for administrative or any other reasons, the processing fees shall not be refunded. The shortlisted consultants will be issued RPF documents and provided 30 days from the issue date of RPF documents to submit the bids. The RFP invitee will be based on QCBS (Quality and Cost Based Selection). Detailed scope of work and terms of reference shall be provided in the RFP. If required, a pre-proposal conference will be organized after issue of RPF to discuss and make changes to the RPF document. Any communication should be through Email/Fax/RPAD to the person and address i.e. Superintending Engineer-II Meerut Development Authority Meerut Ph. 0121-2649198, 2641910, Fax No. 0121-2640911 Mob. 09412784155 Email:[email protected]. EOI shall be submitted by RPAD/speed post only before 31st August, 2015 to the address mentioned above Any EOI received after due date shall be returned unopened. -

![" *!' Trdvd, ERS]Zxyzd F Uvc ]V D 0DUND] FOHDUHG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7407/trdvd-ers-zxyzd-f-uvc-v-d-0dund-fohduhg-1127407.webp)

" *!' Trdvd, ERS]Zxyzd F Uvc ]V D 0DUND] FOHDUHG

) 0&+1 % !. !% !. VRGR $"#(!#1')VCEBRS WWT!Pa!RT%&!$"#1$# $(")$!*+, ,01-1,-2 +,-./ !0,3 4 1 ! ( *(*(2 *&&* 3"4 7( 1?*&1?( ,, &O, +(,- ,78 ? @-?1, @-7@(* +(1(+(8( &- 4"56'1& 1,7/( )&8-(* *8-(+7,(+ ? B7( 8- 17 8-+/- +(-+7 -3+(@+ AB3+ , 8 %&49: $$' ;< - . ././0 ,1 = * ( ( +(,- admitted to isolation wards in various States in the country n its biggest spike till date, following the disclosure that IIndia over the past 24 hours they had attended the Tablighi till Wednesday night recorded conference. A total of 16 States 386 new cases of coronavirus have been searching for taking the tally to 1,906 with Tablighi members. the Government blaming the According reports, at least spurt in cases on the travel by 200 from Karnataka, 140 from members of Tablighi Jamaat Andhra Pradesh and 45 from and asserted that it was not a Telangana have been identi- national trend. fied. The total number of “The number of positive those who attended the con- cases has gone up since ference varies from State to Tuesday. One of main reasons State with Maharashtra listing for it is travel by members of 185 and Karnataka estimating Tablighi. This is not a nation- 342 to have participated in the al trend,” said Lav Agarwal, meeting. Joint Secretary in the Union With the Tabligh incident Ministry of Health. spiking the coronavirus num- According to Ministry’s bers in the country, Prime website, the total number of Minister Narendra Modi spoke active COVID-19 cases to Maharashtra Chief Minister reached 1,637 in India by and asked the State to trace out Wednesday noon, whereas the & P the missing Jamaat members death toll has risen to 42 from "#$%&'() * .% who attended the Delhi con- 32 recorded on Tuesday. -

Project Summary

Project Summary Proposed Protected forest land to be diverted for Doubling of Railway Track from (Km No.- 0.00 to 80.30) Roza to Sitapur Railway {KM No.- 0.00 – 11.00 in Shahjahanpur district}, {KM No.- 11.00 to 28.00 & 34.00 to 46.00 in Lakhimpur Kheri district}, {KM No.- 28.00 to 34.00 in Hardoi district} and {KM No.- 46.00 to 80.30 in Sitapur district} in Northern Railway Division Moradabad. District wise details of forest land and non forest land are as follows: Sr. No. DISTRICT PROTECTED NON FOREST FOREST LAND LAND Area (in Ha) Area (in Ha) 1 Shahjahanpur 8.80 0.0175 2 Lakhimpur Kheri 24.06 0.3235 3 Hardoi 6.1133 0.0851 4 Sitapur 30.6259 0.6435 Total Area 69.5992 1.0696 Mahesh Chand Executive Engineer/Con Northern Railway,Moradabad Area Calculation Sheet Proposed Protected Forest Land to be Diverted For Proposed new 2nd line along with existing Railway line under Roza - Sitapur Railway Track (Km. no. 0.00 - 80.30) Doubling Project of Northern Railway, from Km. 0.00 to 11.00, in Moradabad Division, District: Shahjahanpur (Uttar Pradesh) Protected Forest Land Area Calculation From To Length Width Area Area Sr. No. (Km) (Km) (m) (m) (SqM) (Ha) 1 1.900 7.360 5460.00 8.00 43680.00 4.3680 2 8.670 11.000 2330.00 8.00 18640.00 1.8640 7790.00 62320.00 6.2320 Proposed Protected Forest Land Area 6.2320Ha Protected Forest Land along Railway Yards Forest Land Area Calculation From To Length Width Area Area Sr. -

Prefrenceformat Upcircle190718.Pdf

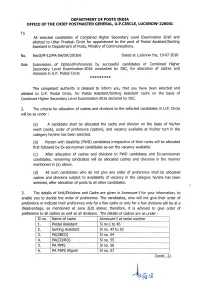

DEPARTMENT OF POSTS INDIA oFFICE OF THE CHIEF POSTMASTER GENERAL, U.P.CIRCLE, LUCKNOW-226OOL All selected candidates of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination 2016 and allotted to Uttar Pradesh Circle for appointment to the post of Postal Assistant/Softing Assistant in Department of Posts, Ministry of Communications. No. RecttiM-12/PA-SA/DR/20L816 Dated at Lucknow the, 19-07-2018 Sub: Submission. of Option/Preferences by successful candidates of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination-2016 conducted by SSC, for allocation of cadres and divisions in U.P. Postal Circle ********* The competent authority is pleased to inform you, that you have been selected and allotted to U.P. Postal Circle, for Postal Assistant/Sorting Assistant cadre on the basis of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination-2016 declared by SSC. 2. The criteria for allocation of cadres and divisions to the selbcted candidates in U.P. Circle will be as under : (a) A candidate shall be allocated the cadre and division on the basis of his/her merit (rank), order of preference (option), and vacanry available at his/her turn in the category he/she has been selected. (b) Person with disability (PWD) candidates irrespective of their ranks will be allocated first followed by Ex-seruiceman candidates as per the vacancy available. (c) After allocation of cadres and divisions to PWD candidates and Ex-seruiceman candidates, remaining candidates will be allocated cadres and divisions in the manner mentioned in (a) above. (d) All such candidates who do not give any order of preference shall be allocated cadres and divisions subject to availability of vacanry in the category he/she has been selected, after allocation of posts to all other candidates. -

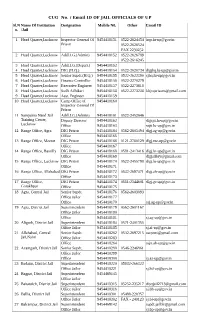

CUG No. / Email ID of JAIL OFFICIALS of up Sl.N Name of Institution Designation Mobile N0

CUG No. / Email ID OF JAIL OFFICIALS OF UP Sl.N Name Of Institution Designation Mobile N0. Other Email ID o. /Jail 1 Head Quarter,Lucknow Inspector General Of 9454418151 0522-2624454 [email protected] Prison 0522-2626524 FAX 2230252 2 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418152 0522-2626789 0522-2616245 3 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Depart.) 9454418153 4 Head Quarter,Lucknow DIG (H.Q.) 9454418154 0522-2620734 [email protected] 5 Head Quarter,Lucknow Senior Supdt.(H.Q.) 9454418155 0522-2622390 [email protected] 6 Head Quarter,Lucknow Finance Controller 9454418156 0522-2270279 7 Head Quarter,Lucknow Executive Engineer 9454418157 0522-2273618 8 Head Quarter,Lucknow Sodh Adhikari 9454418158 0522-2273238 [email protected] 9 Head Quarter,Lucknow Asst. Engineer 9454418159 10 Head Quarter,Lucknow Camp Office of 9454418160 Inspector General Of Prison 11 Sampurna Nand Jail Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418161 0522-2452646 Training Center, Deputy Director 9454418162 [email protected] Lucknow Office 9454418163 [email protected] 12 Range Office, Agra DIG Prison 9454418164 0562-2605494 [email protected] Office 9454418165 13 Range Office, Meerut DIG Prison 9454418166 0121-2760129 [email protected] Office 9454418167 14 Range Office, Bareilly DIG Prison 9454418168 0581-2413416 [email protected] Office 9454418169 [email protected] 15 Range Office, Lucknow DIG Prison 9454418170 0522-2455798 [email protected] Office 9454418171 16 Range Office, Allahabad DIG Prison 9454418172 0532-2697471 [email protected] Office 9454418173 17 Range Office, DIG Prison 9454418174 0551-2344601 [email protected] Gorakhpur Office 9454418175 18 Agra, Central Jail Senior Supdt. -

District Name: Amroha

District Name: Amroha District Name: Amroha DISTRICT Amroha NAME STATE Uttar Pradesh YEAR 2020-21 As – Is Scenario Aggregate Demand • Map the District Map the Primary Demand • Topography Agriculture – Major Crops • Climate Animal Husbandry • Economic Profile Horticulture • Literacy Poultry • Population Others • Identify the Target Population Producer Groups/ SHG Base Map the Secondary Demand • Population of District Major manufacturing clusters • Rural Urban Products/ Trade • Gender • Large Towns/ Villages Map the Service/ Tertiary • Map the Infra Sector • Skill Training Centers Retail across schemes and Tourism departments long and Others short term Map the Traditional Arts and • Current Courses and Crafts performance (E/T/P) SHG Map emerging sectors IT … Self-Employment opportunity Analyse the Gap Action Plan What’s the SWOT for the • Develop Execution plan district (skill and livelihood • Baseline data ecosystem perspective) ? • What are we trying to achieve What are the Demand Supply through this activity(physical and Gaps – aggregate and block other targets) level? • Target audience/beneficiary Migration – Inward and Identify Sectors roles and Outward? courses Knowledge Partners TPs Budget and other resources Develop monitoring and evaluation plan& templates Perceived risks and mitigation strategies 2 District Name: Amroha District Information:- District Name: Amroha District Amroha lies in the west of Moradabad District adjoining district Hapur, Sambhal & Buland Shahar,Bijnor. The district came into being on 15th April 1997 in the memory of famous social reformer Sant Mahatama Jyotiba Phule by combining Amroha, Dhanora & Hasanpur Tehsils of Moradabad district vide UP Gazette no. 1071/1-5-97/224/sa-5 dated 15th April 1997 whose headoffice is situated in the ancient city Amroha.