02 B.A.C. Ajith Balasooriya.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Commanders of the LTTE

4/29/2016 List of commanders of the LTTE Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of commanders of the LTTE From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of commanders of theLiberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers, a separatist militant Tamil nationalist organisation, which operated in northern and eastern Sri Lanka from late 1970s to May 2009, until it was defeated by the Sri Lankan Military.[1][2] Date & Place Date & Place Nom de Guerre Real Name Position(s) Notes of Birth of Death Thambi (used only by Velupillai 26 November 1954 19 May Leader of the LTTE Prabhakaran was the supreme closest associates) and Prabhakaran † Velvettithurai 2009(aged 54)[3][4][5] leader of LTTE, which waged a Anna (elder brother) Vellamullivaikkal 25year violent secessionist campaign in Sri Lanka. His death in Nanthikadal lagoon,Vellamullivaikkal,Mullaitivu, brought an immediate end to the Sri Lankan Civil War. Pottu Amman alias Shanmugalingam 1962 18 May 2009 Leader of Tiger Pottu Amman was the secondin Papa Oscar alias Sivashankar † Nayanmarkaddu[6] (aged 47) Organization Security command of LTTE. His death was Sobhigemoorthyalias Kailan Vellamullivaikkal Intelligence Service initially disputed because the dead (TOSIS) and Black body was not found. But in Tigers October 2010,TADA court judge K. Dakshinamurthy dropped charges against Amman, on the Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, accepting the CBI's report on his demise.[7][8] Selvarasa Shanmugam 6 April 1955 Leader of LTTE since As the chief arms procurer since Pathmanathan (POW) Kumaran Kankesanthurai the death of the origin of the organisation, alias Kumaran Tharmalingam Prabhakaran. -

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London Phd In

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London PhD in Social Anthropology UMI Number: U591568 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591568 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Fig. 1. Aathumkkaavadi DECLARATION I, Jane Derges, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated the thesis. ABSTRACT Following twenty-five years of civil war between the Sri Lankan government troops and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a ceasefire was called in February 2002. This truce is now on the point of collapse, due to a break down in talks over the post-war administration of the northern and eastern provinces. These instabilities have lead to conflicts within the insurgent ranks as well as political and religious factions in the south. This thesis centres on how the anguish of war and its unresolved aftermath is being communicated among Tamils living in the northern reaches of Sri Lanka. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Vaddukoddai Resolution

Vaddukoddai Resolution Unanimously adopted at the First National Convention of the TAMIL UNITED LIBERATION FRONT held at VADDUKODDAI on 14-5-1976 Chairman: S.J.V. Chelvanayakam Q.C., M.P. (K.K.S) [A Translation] Political Resolution Unanimously Adopted at the 1st National Convention of the Tamil United Liberation Front Held at Pannakam (Vaddukoddai Constituency) on 14-5-76, Presided over by Mr. Chelvanayakam, Q.C, M.P. Whereas throughout the centuries from the dawn of history the Sinhalese and Tamil nations have divided between them the possession of Ceylon, the Sinhalese inhabiting the interior of the country in its Southern and Western parts from the river Walawe to that of Chilaw and the Tamils possessing the Northern and Eastern districts; And whereas the Tamil Kingdom was overthrown in war and conquered by the Portuguese in 1619 and from them by the Dutch and the British in turn independent of the Sinhalese Kingdoms; And whereas the British Colonists who ruled the territories of the Sinhalese and Tamil Kingdoms separately joined under compulsion the territories of the Sinhalese Kingdoms for purposes of administrative convenience on the recommendation of the Colebrooke Commission in 1833; And whereas the Tamil Leaders were in the forefront of the Freedom movement to rid Ceylon of colonial bondage which ultimately led to the grant of independence to Ceylon in 1948; And whereas the foregoing facts of history were completely overlooked and power was transferred to the Sinhalese nation over the entire country on the basis of a numerical -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Pattukkottai Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Madhavan Selvarani (M) A21, New Housing Unit, Ponnavarayankottai, , 2 16/11/2020 Alangaram Ramanujam (F) 38-1/38, Taste Bakery Colony Rajapalayam Street, Pattukottai, , 3 16/11/2020 Indrani Alangaram (H) 38-1/38, Taste Bakery Colony Rajapalayam Street, Pattukottai, , 4 16/11/2020 RAMYABHARATHI SRI RAJAMOHAN (F) 27D, THACHA STREET, R M PATTUKKOTTAI, , 5 16/11/2020 Aishwarya K Kamaraj (F) 7, Kondapa Nayakan Palayam, Pattukkottai, , 6 16/11/2020 RAGAVENDHIRAN V VEERA K (F) 33, BHARATHI NAGAR, PATTUKKOTTAI, , 7 16/11/2020 rajeshwari Ragulgandhi Ragulgandhi ragulgandhi 246/3A, Adhithiravidar (H) pallikondan, pallikondan, , 8 16/11/2020 rajeshwari Ragul gandhi Ragul ganthi ragul gandhi 246/3A, adhithiravidar street, (H) pallikondan, , 9 16/11/2020 MOHAMED JAMEEL RAJIK AHAMED (F) 38B, AMBETHKAR NAGAR, RAJIK AHAMED ADIRAMPATTINAM, , 10 16/11/2020 MUSTHAQ AHAMED NIJAMUDEEN (F) 3, AMBETHKAR NAGAR, ADIRAMPATTINAM, , £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location designated location under Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office under $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated rule 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. -

Jfcqjsptlpq Learning-Politics-From

LEARNING POLITICS FROM SIVARAM The Life and Death of a Revolutionary Tamil Journalist in Sri Lanka MARK P. WHITAKER Pluto P Press LONDON • ANN ARBOR, MI Whitaker 00 PLUTO pre iii 14/11/06 08:40:31 First published 2007 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 839 Greene Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Mark P. Whitaker 2007 The right of Mark P. Whitaker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Hardback ISBN-10 0 7453 2354 5 ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2354 1 Paperback ISBN-10 0 7453 2353 7 ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2353 4 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, Fortescue, Sidmouth, EX10 9QG, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Printed and bound in the European Union by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne, England Whitaker 00 PLUTO pre iv 14/11/06 08:40:31 CONTENTS Acknowledgements vi Note on Transliteration, Translation, Names, and Neutrality ix Three Prologues xi 1. Introduction: Why an Intellectual Biography of Sivaram Dharmeratnam? 1 2. Learning Politics from Sivaram 18 3. The Family Elephant 32 4. Ananthan and the Readers’ Circle 52 5. From SR to Taraki – A ‘Serious Unserious’ Journey 79 6. -

Sri Lanka: Tamil Politics and the Quest for a Political Solution

SRI LANKA: TAMIL POLITICS AND THE QUEST FOR A POLITICAL SOLUTION Asia Report N°239 – 20 November 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. TAMIL GRIEVANCES AND THE FAILURE OF POLITICAL RESPONSES ........ 2 A. CONTINUING GRIEVANCES ........................................................................................................... 2 B. NATION, HOMELAND, SEPARATISM ............................................................................................. 3 C. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT AND AFTER ................................................................................ 4 D. LOWERING THE BAR .................................................................................................................... 5 III. POST-WAR TAMIL POLITICS UNDER TNA LEADERSHIP ................................. 6 A. RESURRECTING THE DEMOCRATIC TRADITION IN TAMIL POLITICS .............................................. 6 1. The TNA ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Pro-government Tamil parties ..................................................................................................... 8 B. TNA’S MODERATE APPROACH: YET TO BEAR FRUIT .................................................................. 8 1. Patience and compromise in negotiations -

Sc Spl 03/2014

SC SPL 03/2014 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA Declaration under and in terms of Article 157A(4) of the Constitution (As amended by the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution) of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Hikkadu Koralalage Don Chandrasoma G -16, National Housing Scheme, Polhena, Kelaniya. Petitioner SC SPL No. 03/2014 Vs. 1. Mawai S. Senathirajah Secretary, Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi, 30, Martin Road, Jaffna. 1(a) K. Thurairasasingham Secretary, Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi, 30, Martin Road, Jaffna. (Substituted 1st Respondent) 1 SC SPL 03/2014 1. Mahinda Deshapriya Commissioner of Elections, Elections Secretariat, Sarana Mawatha, Rajagiriya. 2. Hon. Attorney General, Attorney General’s Department Colombo 12. Respondent Before : Priyasath Dep, PC.CJ Upaly Abeyrathne, J Anil Gooneratne J. Counsel : Dharshan Weerasekera with Madhubashini Rajapaksha for Petitioner. K. Kanag-Iswaran, PC with M.A. Sumanthiran, Viran Corea and Niran Ankertel for 1A Respondent. Nerin Pulle, DSG with Suren Gnanaraj, SC for AG. 2 SC SPL 03/2014 Argued on : 18.02.2016 Written Submissions filed on : 18.04.2016 & 03.05.2016 Decided on : 04.08.2017 Priyasath Dep, PC,CJ. The Petitioner filed this action under and in terms of Article 157A (4) of the Constitution (as amended by the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution), seeking a declaration that the Illankai Thamil Arasu Kachchi (hereinafter referred to as “ITAK”) is a political party which has as its “aims” and “objects” the establishment of a separate State within the territory of Sri Lanka. The Petitioner by his Petition dated 27th March 2014, prayed for following reliefs: i) A declaration that ITAK is a political party which has as one of its “aims” and “objects” the establishment of a separate State within the territory of Sri Lanka. -

A Study of Violent Tamil Insurrection in Sri Lanka, 1972-1987

SECESSIONIST GUERRILLAS: A STUDY OF VIOLENT TAMIL INSURRECTION IN SRI LANKA, 1972-1987 by SANTHANAM RAVINDRAN B.A., University Of Peradeniya, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1988 @ Santhanam Ravindran, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Political Science The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date February 29, 1988 DE-6G/81) ABSTRACT In Sri Lanka, the Tamils' demand for a federal state has turned within a quarter of a century into a demand for the independent state of Eelam. Forces of secession set in motion by emerging Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism and the resultant Tamil nationalism gathered momentum during the 1970s and 1980s which threatened the political integration of the island. Today Indian intervention has temporarily arrested the process of disintegration. But post-October 1987 developments illustrate that the secessionist war is far from over and secession still remains a real possibility. -

Republic at 40

! 24 Interview From Federalism to Separatism: The Impact of the 1970-72 Constitution- Making Process on Tamil Nationalism’s Ideological Transformation g D. Sithadthan1 1 Former Member of Parliament; Leader, People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE). This interview was conducted by Luwie Ganeshathasan on 20th July 2012 in Colombo. ! ! From a Tamil perspective, what were the broad political issues of the post-independence period and what were the main political and constitutional challenges that the Tamil people faced? Opinion was divided at that time among the Tamils. Some sections were advocating for a federal state but people like Mr G.G. Ponnambalam were for a unitary state. I think he believed that, at that time since the Tamils were in an advantageous position, that within a unitary state, Tamils could have a major portion of the cake. There was a belief that if the Tamils ask for a federal state they will be confined to the north and east only and will have no share of the power in the central government. The Tamil people’s opposition was on an issue-by-issue basis. For example, there was opposition to the design of the national flag because the Tamil people felt it is a symbol of the Sinhala people only. Later the green and orange stripes were added to signify the Muslim and Tamil people, but to this day the Tamil people are not willing to accept the national flag as ours. Furthermore, in spite of Section 29 of the Soulbury Constitution and the famous Kodeeswaran Case, the Sinhala Only Act was passed. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

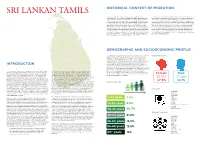

Sri Lankan Tamils Historical Context of Migration

SRI LANKAN TAMILS HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF MIGRATION The fi rst international migration wave occurred right after the According to the Department of Home Affairs (2016), the fi rst Sri Lankan independence in 1948, mostly consisted of professionals and students immigrants to Australia were recruited to work in the cane plantation in mainly from the upper class and upper caste backgrounds (Van Hear the late 19th century. Many Tamils and Burghers migrated to Australia et al. 2004). People with English profi ciency migrated during this time after the introduction of the Sinhala Only Act in 1956. The changes in (Orjuela 2008). The fi rst wave cannot be labelled as ‘forced’ migration Australia’s immigration policies in the late 1960s and early 1970s paved a or ‘victim’ experience. The strength of literacy, English competency, path for further Tamil migration to Australia. While there were many who affordability, and established attachments abroad might have been fl ed the war and reached Australia as humanitarian entrants, after the among the main reasons for Tamils to migrate at that time. The second ethnic genocide in 1983 and 2009, there was also a signifi cant number migration wave occurred after the election in 1956. It consisted of those of Tamils migrating under skilled and family migration programs. It is who were in search of higher education and employment opportunities. also important to note the Australian government relentless campaign The civil war between Tamil militants and the government intensifi ed against asylum seekers from Sri Lanka in the post-war context despite after 1980s causing the next waves of Tamil migration, mostly in the form the reporting on human rights violations and ongoing ethnic outbidding of asylum after the riot in 1983, increasingly from the lower class and in Sri Lanka (Fernandes 2019).