Sri Lankan Tamils Historical Context of Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London Phd In

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London PhD in Social Anthropology UMI Number: U591568 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591568 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Fig. 1. Aathumkkaavadi DECLARATION I, Jane Derges, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated the thesis. ABSTRACT Following twenty-five years of civil war between the Sri Lankan government troops and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a ceasefire was called in February 2002. This truce is now on the point of collapse, due to a break down in talks over the post-war administration of the northern and eastern provinces. These instabilities have lead to conflicts within the insurgent ranks as well as political and religious factions in the south. This thesis centres on how the anguish of war and its unresolved aftermath is being communicated among Tamils living in the northern reaches of Sri Lanka. -

The Case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences 2017 40 (1): 41-52 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/sljss.v40i1.7500 RESEARCH ARTICLE Collective ritual as a way of transcending ethno-religious divide: the case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka# Anton Piyarathne* Department of Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Sri Lanka. Abstract: Sri Lanka has been in the prime focus of national and who are Sinhala speakers, are predominantly Buddhist, international discussions due to the internal war between the whereas the ethnic Tamils, who communicate in the Tamil Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan language, are primarily Hindu. These two ethnic groups government forces. The war has been an outcome of the are often recognised as rivals involved in an “ethnic competing ethno-religious-nationalisms that raised their heads; conflict” that culminated in war between the LTTE (the specially in post-colonial Sri Lanka. Though today’s Sinhala Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a military movement and Tamil ethno-religious-nationalisms appear as eternal and genealogical divisions, they are more of constructions; that has battled for the liberation of Sri Lankan Tamils) colonial inventions and post-colonial politics. However, in this and the government. Sri Lanka suffered heavily as a context it is hard to imagine that conflicting ethno-religious result of a three-decade old internal war, which officially groups in Sri Lanka actually unite in everyday interactions. ended with the elimination of the leadership of the LTTE This article, explains why and how this happens in a context in May, 2009. -

Sri Lanka Anketell Final

The Silence of Sri Lanka’s Tamil Leaders on Accountability for War Crimes: Self- Preservation or Indifference? Niran Anketell 11 May 2011 A ‘wikileaked’ cable of 15 January 2010 penned by Patricia Butenis, U.S Ambassador to Sri Lanka, entitled ‘SRI LANKA WAR-CRIMES ACCOUNTABILITY: THE TAMIL PERSPECTIVE’, suggested that Tamils within Sri Lanka are more concerned about economic and social issues and political reform than about pursuing accountability for war crimes. She also said that there was an ‘obvious split’ between diaspora Tamils and Tamils within Sri Lanka on how and when to address the issue of accountability. Tamil political leaders for their part, notably those from the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), had made no public remarks on the issue of accountability until 18 April 2011, when they welcomed the UN Secretary-General’s Expert Panel report on accountability in Sri Lanka. That silence was observed by some as an indication that Tamils in Sri Lanka have not prioritised the pursuit of accountability to the degree that their diaspora counterparts have. At a panel discussion on Sri Lanka held on 10 February 2011 in Washington D.C., former Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia, Donald Camp, cited the Butenis cable to argue that the United States should shift its focus from one of pursuing accountability for war abuses to ‘constructive engagement’ with the Rajapakse regime. Camp is not alone. There is significant support within the centres of power in the West that a policy of engagement with Colombo is a better option than threatening it with war crimes investigations and prosecutions. -

Vaddukoddai Resolution

Vaddukoddai Resolution Unanimously adopted at the First National Convention of the TAMIL UNITED LIBERATION FRONT held at VADDUKODDAI on 14-5-1976 Chairman: S.J.V. Chelvanayakam Q.C., M.P. (K.K.S) [A Translation] Political Resolution Unanimously Adopted at the 1st National Convention of the Tamil United Liberation Front Held at Pannakam (Vaddukoddai Constituency) on 14-5-76, Presided over by Mr. Chelvanayakam, Q.C, M.P. Whereas throughout the centuries from the dawn of history the Sinhalese and Tamil nations have divided between them the possession of Ceylon, the Sinhalese inhabiting the interior of the country in its Southern and Western parts from the river Walawe to that of Chilaw and the Tamils possessing the Northern and Eastern districts; And whereas the Tamil Kingdom was overthrown in war and conquered by the Portuguese in 1619 and from them by the Dutch and the British in turn independent of the Sinhalese Kingdoms; And whereas the British Colonists who ruled the territories of the Sinhalese and Tamil Kingdoms separately joined under compulsion the territories of the Sinhalese Kingdoms for purposes of administrative convenience on the recommendation of the Colebrooke Commission in 1833; And whereas the Tamil Leaders were in the forefront of the Freedom movement to rid Ceylon of colonial bondage which ultimately led to the grant of independence to Ceylon in 1948; And whereas the foregoing facts of history were completely overlooked and power was transferred to the Sinhalese nation over the entire country on the basis of a numerical -

SRI LANKA: Land Ownership and the Journey to Self-Determination

Land Ownership and the Journey to Self-Determination SRI LANKA Country Paper Land Watch Asia SECURING THE RIGHT TO LAND 216 Acknowledgments Vavuniya), Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka, Hadabima Authority of Sri Lanka, National This paper is an abridged version of an earlier scoping Aquaculture Development Authority in Sri study entitled Sri Lanka Country Report: Land Watch Asia Lanka, Urban Development Authority, Coconut Study prepared in 2010 by the Sarvodaya Shramadana Development Authority, Agricultural and Agrarian Movement through the support of the International Land Insurance Board, Coconut Cultivation Board, Coalition (ILC). It is also written as a contribution to the Janatha Estate Dvt. Board, National Livestock Land Watch Asia (LWA) campaign to ensure that access Development Board, National Water Supply and to land, agrarian reform and sustainable development for Drainage Board, Palmyra Dvt. Board, Rubber the rural poor are addressed in development. The LWA Research Board of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka Tea Board, campaign is facilitated by the Asian NGO Coalition for Land Reform Commission, Sri Lanka State Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ANGOC) and Plantation Cooperation, State Timber Cooperation, involves civil society organizations in Bangladesh, Geological Survey and Mines Bureau, Lankem Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Tea and Rubber Plantation Limited, Mahaweli Philippines, and Sri Lanka. Livestock Enterprise Ltd, National Institute of Education, National Institute of Plantation Mgt., The main paper was written by Prof. CM Madduma Department of Wildlife Conservation Bandara as main author, with research partners Vindya • Non-Governmental Organizations Wickramaarachchi and Siripala Gamage. The authors Plan Sri Lanka, World Vision Lanka, CARE acknowledge the support of Dr. -

Jfcqjsptlpq Learning-Politics-From

LEARNING POLITICS FROM SIVARAM The Life and Death of a Revolutionary Tamil Journalist in Sri Lanka MARK P. WHITAKER Pluto P Press LONDON • ANN ARBOR, MI Whitaker 00 PLUTO pre iii 14/11/06 08:40:31 First published 2007 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 839 Greene Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Mark P. Whitaker 2007 The right of Mark P. Whitaker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Hardback ISBN-10 0 7453 2354 5 ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2354 1 Paperback ISBN-10 0 7453 2353 7 ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2353 4 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, Fortescue, Sidmouth, EX10 9QG, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Printed and bound in the European Union by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne, England Whitaker 00 PLUTO pre iv 14/11/06 08:40:31 CONTENTS Acknowledgements vi Note on Transliteration, Translation, Names, and Neutrality ix Three Prologues xi 1. Introduction: Why an Intellectual Biography of Sivaram Dharmeratnam? 1 2. Learning Politics from Sivaram 18 3. The Family Elephant 32 4. Ananthan and the Readers’ Circle 52 5. From SR to Taraki – A ‘Serious Unserious’ Journey 79 6. -

Conjuring up Spirits of the Past" Identifications in Public Ritual of Living Persons with Persons from the Past

PETER SCHALK "Conjuring Up Spirits of the Past" Identifications in Public Ritual of Living Persons with Persons from the Past Introduction Karl Marx pointed out in the first chapter of Der achzehnte Brumaire des Louis Bonaparte ("The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon") from 1852 that just as people seem to be occupied with revolutionising themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, it is precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis that they anxiously conjure up the spir- its of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time- honoured disguise and borrowed language. Thus, Luther put on the mask of the Apostle Paul. (Marx 1972: 115.) Marx called this also Totenbeschwörung or Totenerweckung, "conjuring up spirits of the past", and he saw two pos- sible outcomes of it. It can serve the purpose of glorifying the new strug- gles, but it can also end up in just parodying the old. It can magnify the given task in the imagination, but it can also result in a recoil from its solu- tion in reality. It can result in finding once more the spirit of revolution, but may also make its ghost walk again. (Marx 1972: 116.) There is a risk in repeating the past. It may just end up in comedy or even ridicule. This putting on the mask of past generations or Totenbeschwörung, I re- fer to here as historical approximation/synchronisation. This historical ap- proximation to, and synchronisation of, living persons with persons of the past is done as a conscious intellectual effort by ideologues to identify per- sons and events separated in space and time because of a similarity. -

Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 51–70 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.145 Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society Kalinga Tudor Silva1 Abstract More than a decade after the end of the 26-year old LTTE—led civil war in Sri Lanka, a particular section of the Jaffna society continues to stay as Internally Displaced People (IDP). This paper tries to unravel why some low caste groups have failed to end their displacement and move out of the camps while everybody else has moved on to become a settled population regardless of the limitations they experience in the post-war era. Using both quantitative and qualitative data from the affected communities the paper argues that ethnic-biases and ‘caste-blindness’ of state policies, as well as Sinhala and Tamil politicians largely informed by rival nationalist perspectives are among the underlying causes of the prolonged IDP problem in the Jaffna Peninsula. In search of an appropriate solution to the intractable IDP problem, the author calls for an increased participation of these subaltern caste groups in political decision making and policy dialogues, release of land in high security zones for the affected IDPs wherever possible, and provision of adequate incentives for remaining people to move to alternative locations arranged by the state in consultation with IDPs themselves and members of neighbouring communities where they cannot be relocated at their original sites. Keywords Caste, caste-blindness, ethnicity, nationalism, social class, IDPs, Panchamars, Sri Lanka 1Department of Sociology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] © 2020 Kalinga Tudor Silva. -

Sri Lanka: Tamil Politics and the Quest for a Political Solution

SRI LANKA: TAMIL POLITICS AND THE QUEST FOR A POLITICAL SOLUTION Asia Report N°239 – 20 November 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. TAMIL GRIEVANCES AND THE FAILURE OF POLITICAL RESPONSES ........ 2 A. CONTINUING GRIEVANCES ........................................................................................................... 2 B. NATION, HOMELAND, SEPARATISM ............................................................................................. 3 C. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT AND AFTER ................................................................................ 4 D. LOWERING THE BAR .................................................................................................................... 5 III. POST-WAR TAMIL POLITICS UNDER TNA LEADERSHIP ................................. 6 A. RESURRECTING THE DEMOCRATIC TRADITION IN TAMIL POLITICS .............................................. 6 1. The TNA ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Pro-government Tamil parties ..................................................................................................... 8 B. TNA’S MODERATE APPROACH: YET TO BEAR FRUIT .................................................................. 8 1. Patience and compromise in negotiations -

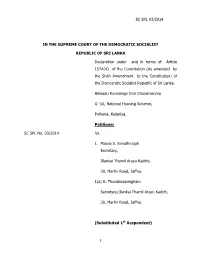

Sc Spl 03/2014

SC SPL 03/2014 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA Declaration under and in terms of Article 157A(4) of the Constitution (As amended by the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution) of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Hikkadu Koralalage Don Chandrasoma G -16, National Housing Scheme, Polhena, Kelaniya. Petitioner SC SPL No. 03/2014 Vs. 1. Mawai S. Senathirajah Secretary, Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi, 30, Martin Road, Jaffna. 1(a) K. Thurairasasingham Secretary, Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi, 30, Martin Road, Jaffna. (Substituted 1st Respondent) 1 SC SPL 03/2014 1. Mahinda Deshapriya Commissioner of Elections, Elections Secretariat, Sarana Mawatha, Rajagiriya. 2. Hon. Attorney General, Attorney General’s Department Colombo 12. Respondent Before : Priyasath Dep, PC.CJ Upaly Abeyrathne, J Anil Gooneratne J. Counsel : Dharshan Weerasekera with Madhubashini Rajapaksha for Petitioner. K. Kanag-Iswaran, PC with M.A. Sumanthiran, Viran Corea and Niran Ankertel for 1A Respondent. Nerin Pulle, DSG with Suren Gnanaraj, SC for AG. 2 SC SPL 03/2014 Argued on : 18.02.2016 Written Submissions filed on : 18.04.2016 & 03.05.2016 Decided on : 04.08.2017 Priyasath Dep, PC,CJ. The Petitioner filed this action under and in terms of Article 157A (4) of the Constitution (as amended by the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution), seeking a declaration that the Illankai Thamil Arasu Kachchi (hereinafter referred to as “ITAK”) is a political party which has as its “aims” and “objects” the establishment of a separate State within the territory of Sri Lanka. The Petitioner by his Petition dated 27th March 2014, prayed for following reliefs: i) A declaration that ITAK is a political party which has as one of its “aims” and “objects” the establishment of a separate State within the territory of Sri Lanka. -

Ancestral Groups in Sydney, 2011. Urban Geography, 37(7), 985-1008

Johnston, R., Forrest, J., Jones, K., & Manley, D. (2016). The scale of segregation: ancestral groups in Sydney, 2011. Urban Geography, 37(7), 985-1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1139867 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1080/02723638.2016.1139867 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Urban Geography on [date of publication], available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/02723638.2016.1139867 University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ The scale of segregation: ancestral groups in Sydney, 2011 Most studies of urban residential segregation analyse it at a single-scale only, usually the smallest for which relevant census data are available. Following a recent argument that such segregation is multi-scalar, this paper reports on multi-level modelling of the segregation of 42 ancestral groups in Sydney, Australia, looking at its intensity at four separate scales in which segregation at each scale is presented nett of its intensity at all higher-level scales. Most groups are more segregated at the macro- and micro-scales than at two intermediate meso-scales, with variations across them reflecting their size, recency of arrival in Australia, and cultural differences from the host society. The findings are used as the basis for developing a multi-scale appreciation of residential patterning. -

Republic at 40

! 24 Interview From Federalism to Separatism: The Impact of the 1970-72 Constitution- Making Process on Tamil Nationalism’s Ideological Transformation g D. Sithadthan1 1 Former Member of Parliament; Leader, People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE). This interview was conducted by Luwie Ganeshathasan on 20th July 2012 in Colombo. ! ! From a Tamil perspective, what were the broad political issues of the post-independence period and what were the main political and constitutional challenges that the Tamil people faced? Opinion was divided at that time among the Tamils. Some sections were advocating for a federal state but people like Mr G.G. Ponnambalam were for a unitary state. I think he believed that, at that time since the Tamils were in an advantageous position, that within a unitary state, Tamils could have a major portion of the cake. There was a belief that if the Tamils ask for a federal state they will be confined to the north and east only and will have no share of the power in the central government. The Tamil people’s opposition was on an issue-by-issue basis. For example, there was opposition to the design of the national flag because the Tamil people felt it is a symbol of the Sinhala people only. Later the green and orange stripes were added to signify the Muslim and Tamil people, but to this day the Tamil people are not willing to accept the national flag as ours. Furthermore, in spite of Section 29 of the Soulbury Constitution and the famous Kodeeswaran Case, the Sinhala Only Act was passed.