Abigail Adams and Her Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hair Creations Catalogue - 1

Hair Creations Catalogue - 1 2 Welcome Joli Wigs Beautiful Natural Hair Creations Welcome 4 Joli Wigs 5 Luxurious Natural French Top Wigs 6 To all our friends out there who have embraced our existence and who believe in what we are Joli Vie™ 7 doing, thank you. We appreciate you more than you can know and we are privileged to serve Joli Couture™ 9 you. It is your enthusiasm and desire for great hair and artistry that energizes us in our work. Natural Lace Top, Lace Front, PU Tabs 10 Joli Esprit™ 11 Since the beginning of Joli Caméléon, we set out to achieve things that have never been done before. Rather than being tied to one hair source and one factory, we choose to be free to Joli Toujours™ 13 innovate and grow. We source our own high quality materials and take advantage of different French Top, Silicone Panels, Lace Front 14 specialty skills in a small group of personally selected craft factories. We believe that no one Joli Caresse™ 15 factory can be expert in everything they do and that larger factories are challenged to react or Joli Liberté™ 17 innovate fast enough. The success of this strategy is proven by what we have achieved in such a Joli Dancer™ 19 short time. You have made us the fastest growing wig company in the USA and Europe. Natural Toppe™ Hairpieces 22 Joli Flexi Toppe™ 23 We are proud to offer women and children everywhere this comprehensive range of hair Joli French Toppe™ 25 creations, designed just for you, whatever your reason is for wearing hair. -

The Stamp Act Crisis (1765)

Click Print on your browser to print the article. Close this window to return to the ANB Online. Adams, John (19 Oct. 1735-4 July 1826), second president of the United States, diplomat, and political theorist, was born in Braintree (now Quincy), Massachusetts, the son of John Adams (1691-1760), a shoemaker, selectman, and deacon, and Susanna Boylston. He claimed as a young man to have indulged in "a constant dissipation among amusements," such as swimming, fishing, and especially shooting, and wished to be a farmer. However, his father insisted that he follow in the footsteps of his uncle Joseph Adams, attend Harvard College, and become a clergyman. John consented, applied himself to his studies, and developed a passion for learning but refused to become a minister. He felt little love for "frigid John Calvin" and the rigid moral standards expected of New England Congregationalist ministers. John Adams. After a painting by Gilbert Stuart. Adams was also ambitious to make more of a figure than could Courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC- USZ62-13002 DLC). be expected in the local pulpits. So despite the disadvantages of becoming a lawyer, "fumbling and racking amidst the rubbish of writs . pleas, ejectments" and often fomenting "more quarrels than he composes," enriching "himself at the expense of impoverishing others more honest and deserving," Adams fixed on the law as an avenue to "glory" through obtaining "the more important offices of the State." Even in his youth, Adams was aware he possessed a "vanity," which he sought to sublimate in public service: "Reputation ought to be the perpetual subject of my thoughts, and the aim of my behaviour." Adams began reading law with attorney James Putnam in Worcester immediately after graduation from Harvard College in 1755. -

John Adams and Jay's Treaty

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 John Adams and Jay's Treaty Edgar Arthur Quimby The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Quimby, Edgar Arthur, "John Adams and Jay's Treaty" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2781. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2781 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN ADAMS AND JAT'S TREATT by EDQAE ARTHUR QDIMHr B.A. University of Mississippi, 1958 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners V /iiC ^ c r. D e a n , Graduate School Date UMI Number; EP36209 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP36209 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Presidents' Day Family

Schedule at a Glance Smith Center Powers Room Learning Center The Pavilion Exhibit Galleries Accessibility: Performances Hands-on | Crafts Performances | Activities “Make and Take” Craft Activities Special Activities Learning Wheelchairs are available Shaping A New Nation Suffrage Centennial Center at the Visitor Admission 10:00 Desk on a first come, first served basis. Video Popsicle presentations in the Museum Stick Flags 10:30 Mini RFK 10:00 – 11:00 Foyer Elevators are captioned for visitors John & Abigail Adams WPA Murals Smith Center who are deaf or hard 10:30 – 11:10 Suffragist 10:00 – 11:30 Kennedy Scrimshaw of hearing. 11:00 Read Aloud Sashes & Campaign Hats 10:30 – 11:30 10:45 – 11:15 Sunflowers & Buttons James & Dolley Madison 10:00 – 12:30 10:00 – 12:15 Powers Café 11:30 11:10 – 11:50 Colonial Clothes Lucretia Mott Room 11:00 – 12:15 11:15 – 11:40 Adams Astronaut Museum Tour 11:15 – 12:20 Helmets 11:30 – 12:15 12:00 Eleanor Roosevelt 11:15 – 12:30 Restrooms 11:50 – 12:30 PT 109 Cart 12:30 Sojourner Truth Protest Popsicle 12:00 – 1:00 Presidential Press Conference 12:15 – 1:00 Posters Stick Flags 12:30 – 1:00 Museum Evaluation Station Presidential 12:00 – 1:30 12:00 – 1:30 Homes Store 1:00 James & Dolley Madison 12:30 – 1:30 Pavilion Adams Letter Writing 1:00 – 1:30 Astronaut Museum 1:00 – 1:40 to the President Space Cart Lucretia Mott Helmets Lobby 12:30 – 2:15 1:00 – 2:00 1:30 Eleanor Roosevelt 1:15 – 1:45 1:00 – 2:00 Entrance 1:30 – 2:00 2:00 John & Abigail Adams Sojourner Truth 2:00 – 2:30 2:00-2:30 Museum Tour Zines Scrimshaw 2:00 – 2:45 1:00 – 3:30 Mini 2:00 – 3:00 Sensory 2:30 Powerful Women Jeopardy WPA Murals Accommodations: 2:30 – 3:00 2:00 – 3:30 Kennedy The John F. -

Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783

2014 Felicia Y. Thomas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ENTANGLED WITH THE YOKE OF BONDAGE: BLACK WOMEN IN MASSACHUSETTS, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Deborah Gray White and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Entangled With the Yoke of Bondage: Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS Dissertation Director: Deborah Gray White This dissertation expands our knowledge of four significant dimensions of black women’s experiences in eighteenth century New England: work, relationships, literacy and religion. This study contributes, then, to a deeper understanding of the kinds of work black women performed as well as their value, contributions, and skill as servile laborers; how black women created and maintained human ties within the context of multifaceted oppression, whether they married and had children, or not; how black women acquired the tools of literacy, which provided a basis for engagement with an interracial, international public sphere; and how black women’s access to and appropriation of Christianity bolstered their efforts to resist slavery’s dehumanizing effects. While enslaved females endured a common experience of race oppression with black men, gender oppression with white women, and class oppression with other compulsory workers, black women’s experiences were distinguished by the impact of the triple burden of gender, race, and class. This dissertation, while centered on the experience of black women, considers how their experience converges with and diverges from that of white women, black men, and other servile laborers. -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ). -

Abigail Adams As a Typical Massachusetts Woman at the Close of the Colonial Era

V/ax*W ad Close + K*CoW\*l ^V*** ABIGAIL ADAMS AS A TYPICAL MASSACHUSETTS WOMAN AT THE CLOSE OF THE COLONIAL ERA BY MARY LUCILLE SHAY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1917 - UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS m^ji .9../. THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ./?^..f<r*T) 5^.f*.l^.....>> .&*r^ ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF i^S^«4^jr..^^ UA^.tltht^^ Instructor in Charge Approved :....<£*-rTX??. (QS^h^r^r^. lLtj— HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF ZL?Z?.f*ZZS. 376674 * WMF ABIGAIL ARAMS AS A TYPICAL MASSACHUSETTS '.70MJEN AT THE CLOSE OP THE COLONIAL ERA Page. I. Introduction. "The Woman's Part." 1 II. Chapter 1. Domestic Life in Massachusetts at the Close of the Colonial Era. 2 III. Chapter 2. Prominent V/omen. 30 IV. Chapter 3. Abigail Adacs. 38 V. Bibliography. A. Source References 62 B. Secondary References 67 I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/abigailadamsastyOOshay . 1 ABIJAIL ARAMS A3 A ISP1CAL MASSACHUSETTS .VOMAIJ aT THE GLOSS OF THE COLOHIAL SEA. I "The Woman's Part" It was in the late eighteenth century that Abigail Adams lived. It was a time not unlike our own, a time of disturbed international relations, of war. School hoys know the names of the heroes and the statesmen of '76, but they have never heard the names of the women. Those names are not men- tioned; they are forgotten. -

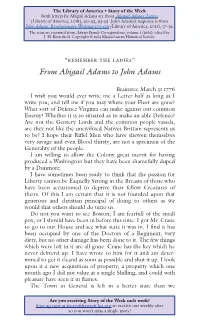

From Abigail Adams to John Adams

The Library of America • Story of the Week Both letters by Abigail Adams are from Abigail Adams: Letters (Library of America, 2016), 90–93, 93–95. John Adams’s response is from John Adams: Revolutionary Writings 1775–1783 (Library of America, 2011), 57–59. The texts are reprinted from Adams Family Correspondence, volume 1 (1963), edited by J. H. Butterfield. Copyright © 1963 Massachusetts Historical Society. “REMEMBER THE LADIES” From Abigail Adams to John Adams Braintree March 31 1776 I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone? What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence? Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be? I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people. I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore. I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us. Do not you want to see Boston; I am fearfull of the small pox, or I should have been in before this time. -

CHRONOLOGY of WOMEN's SUFFRAGE 1776 Abigail Adams

CHRONOLOGY of WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE 1776 Abigail Adams writes to her husband, John Adams, asking him to "remember the ladies" in the new code of laws. Adams replies the men will fight the "despotism of the petticoat. Thus begins the long fight for Women's suffrage. 1869 Wyoming Territory grants suffrage to women 1870 Utah Territory grants suffrage to women 1880 New York State grants school suffrage to women 1890 Wyoming joins the Union as the first state with voting rights for women. By 1900 women also have full suffrage in Utah, Colorado and Idaho. New Zealand is the first nation to give women suffrage 1902 Women of Australia are enfranchised. 1906 Women of Finland are enfranchised. 1912 Suffrage referendums are passed in Arizona, Kansas and Oregon 1913 territory of Alaska grants suffrage 1914 Montana and Nevada grant voting rights to women, 1915 Women of Denmark are enfranchised. 1917 Women win the right to vote in North Dakota, Ohio, Indiana, Rhode Island, Nebraska, Michigan, New York, and Arkansas 1918 Women of Austria, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Scotland, and Wales are enfranchised. 1919 Women of Azerbaijan Republic, Belgium, British East Africa, Holland, Iceland, Luxembourg, Rhodesia, and Sweden are enfranchised. Suffrage Amendment is passed by the US Senate on June 4th and the battle for ratification by at least 36 states begins. 1920 In February the LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS was formed by Carrie Chapman Catt at the close of the National American Women Suffrage Alliance last Convention. The League of Women Voters is to this day one of the country's preeminent nonpartisan voter education groups. -

(Microsoft Powerpoint

Milestones and Key Figures in Women’s History Life in Colonial America 1607-1789 Anne Hutchinson Challenged Puritan religious authorities in Massachusetts Bay Banned by Puritan authorities for: Challenging religious doctrine Challenging gender roles Challenging clerical authority Claiming to have had revelations from God Legal Status of Colonial Women Women usually lost control of their property when they married Married women had no separate legal identity apart from their husband Could NOT: Hold political office Serve as clergy Vote Serve as jurors Legal Status of Colonial Women Single women and widows did have the legal right to own property Women serving as indentured servants had to remain unmarried until the period of their indenture was over The Chesapeake Colonies Scarcity of women, especially in the 17 th century High mortality rate among men Led to a higher status for women in the Chesapeake colonies than those of the New England colonies The Early Republic 1789-1815 Abigail Adams An early proponent of women’s rights A famous letter to John demonstrates that some colonial women hoped to benefit from republican ideals of equality and individual rights “. And by the way in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Remember, men would be tyrants if they could.” --Abigail Adams The Cult of Domesticity / Republican Motherhood The term cult of domesticity refers to the idealization of women in their roles as wives and mothers The term republican mother suggested that women would be responsible for rearing their children to be virtuous citizens of the new American republic By emphasizing family and religious values, women could have a positive moral influence on the American political character The Cult of Domesticity / Republican Motherhood Middle-Class Americans viewed the home as a refuge from the world rather than a productive economic unit. -

Social Studies Summer Project

Person of Interest Project Assignment: The student will choose one person from the course, about whom we will learn, and research the person's life in detail. The student will record details and various pieces of informa<on about their chosen person in a format that is easily understood and will make an oral report. The student is responsible for finding credible informa<on from the internet, books, encyclopedias, etc. Objec<ve: The student's objec<ve is to learn proper research techniques, as well as grasping the importance of individuals throughout the course of U.S. History. People: Christopher Columbus Frederick Douglass John Paul Jones Pocahontas Meriwether Lewis Abigail Adams William Clark John Adams Stonewall Jackson Samuel Adams Susan B. Anthony Benjamin Franklin Elizabeth Cady Stanton King George III Jefferson Davis Patrick Henry Ulysses S. Grant Paul Revere Robert E. Lee Thomas Jefferson Abraham Lincoln the Marquis de LafayeXe John Quincy Adams Thomas Paine John C. Calhoun George Washington Henry Clay Eli Whitney Daniel Webster Alexander Hamilton Harriet Tubman James Madison Clara Barton James Monroe Mary Todd Lincoln Betsy Ross Harriet Beecher Stowe Andrew Jackson Nat Turner Thomas Hooker Charles de Montesquieu John Locke William Penn Instruc<ons: Find the following informa<on for your person of interest. AIer you have researched and found the necessary informa<on, create a poster/power point that includes all the informa<on you found, 3 pictures, and include an essay of at least 2 pages of how your person of interest impacted the United States and you must have all your informa<on and sources properly cited. -

Candi Menu 2021.Indd

menu Wash & Style Wash & Condition (excludes styling) Wash + Condition R95 Wash + Condition Only (LOC Method) R100 Wash + Condition Only (Detangling wash) R150 Wig Wash R130 Blow-Wave (No Wash) Blow-Wave + Iron R125 Blow-Wave + Curls R165 Blow-Wave + Straightening Serum R150 Iron Iron only R100 Silk Press (incl. wash) R495 Upstyle Short (incl. wash) R365 Long (incl. wash) R395 Wigs & Weaves Wigs Wig Installation Combo R390 (Hair Wash + Wig Wash + Wig lines + Wig Style) Personalised Wig-making (excl. wig-cap) R395 Machine Wig-making (excl. wig-cap) R350 Frontal Installation Combo R595 (Hair Wash + Wig lines + Install + Style) Frontal Installation Only R350 Weaves Weave Touch Up (Wash + Fix + Style) R260 Weaves Installation Combo R595 (Wash + Cornrows + Install + Style) Weave Full House Combo R795 (Remove + Hair & Weave Wash + Cornrows + Install + Style) Removals: 30mins 60mins 90mins R90 R170 R270 Removal & Style Combo R295 (*Removal + Hair Wash + Blow-Wave or Wig-lines) *30 minute removal service Hair Treatments (includes wash + styling) Hair Growth Stimulator Hair Treatment R495 Scalp Hair Treatment (great for braids & wigs) R495 Moisture or Protein Treatment R495 Top-Up Treatment (excl. shampoo + styling) R95 Chemical Treatments Relaxer (includes wash + styling) Relaxer: Mizani R395 Relaxer + PH Bond Treatment: Mizani R495 Sensitive Relaxer: Mizani R460 Relaxer: Dark & Lovely R195 Relaxer: Ladine R295 Relaxer Half Head (excl. styling) R100 Texturiser (includes wash + styling) Texturiser: Mizani R390 Texturiser: Ladine R290 Perm & S-Curl