Making Recreational Space: Citizen Involvement in Outdoor Recreation and Park Establishment in British Columbia, 1900-2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

CANADA's MOUNTAIN Rocky Mountain Goats

CANADA'S MOUNTAIN Rocky Mountain Goats CANADA'S MOUNTAIN PLAYGROUNDS BANFF • JASPER • WATERTON LAKES • YOHO KOOTENAY ° GLACIER • MOUNT REVELSTOKE The National Parks of Canada ANADA'S NATIONAL PARKS are areas The National Parks of Canada may, for C of outstanding beauty and interest that purposes of description, be grouped in three have been set apart by the Federal Govern main divisions—the scenic and recreational ment for public use. They were established parks in the mountains of Western Canada; the to maintain the primitive beauty of the land scenic, recreational, wild animals, and historic scape, to conserve the native wildlife of the parks of the Prairie Provinces; and the scenic, country, and to preserve sites of national his recreational, and historic parks of Eastern Can toric interest. As recreational areas they pro ada. In these pages will be found descriptions vide ideal surroundings for the enjoyment of of the national parks in the first group—areas outdoor life, and now rank among Canada's which lie within the great mountain regions outstanding tourist attractions. of Alberta and British Columbia. Canada's National Park system teas estab * * * lished in 1SS5, when a small area surrounding mineral hot springs at Banff in the Rocky This publication is compiled in co-operation Mountains was reserved as a public posses with the National Parks Branch, Department sion. From this beginning has been developed of Northern Affairs and National Resources. the great chain of national playgrounds note Additional information concerning these parks stretching across Canada from the Selkirk may be obtained from the Park Superintend Mountains in British Columbia to the Atlantic ents, or from the Canadian Government Travel Coast of Nova Scotia. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

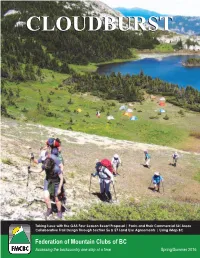

Cloudburstcloudburst

CLOUDBURSTCLOUDBURST Taking Issue with the GAS Four Season Resort Proposal | Parks and their Commercial Ski Areas Collaborative Trail Design Through Section 56 & 57 Land Use Agreements | Using iMap BC Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Accessing the backcountry one step at a time Spring/Summer 2016 CLOUDBURST Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Published by : Working on your behalf Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC PO Box 19673, Vancouver, BC, V5T 4E7 The Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC (FMCBC) is a democratic, grassroots organization In this Issue dedicated to protecting and maintaining access to quality non-motorized backcountry rec- reation in British Columbia’s mountains and wilderness areas. As our name indicates we are President’s Message………………….....……... 3 a federation of outdoor clubs with a membership of approximately 5000 people from 34 Recreation & Conservation.……………...…… 4 clubs across BC. Our membership is comprised of a diverse group of non-motorized back- Member Club Grant News …………...………. 11 country recreationists including hikers, rock climbers, mountaineers, trail runners, kayakers, Mountain Matters ………………………..…….. 12 mountain bikers, backcountry skiers and snowshoers. As an organization, we believe that Club Trips and Activities ………………..…….. 15 the enjoyment of these pursuits in an unspoiled environment is a vital component to the Club Ramblings………….………………..……..20 quality of life for British Columbians and by acting under the policy of “talk, understand and Some Good Reads ……………….…………... 22 persuade” we advocate for these interests. Garibaldi 2020…... ……………….…………... 27 Membership in the FMCBC is open to any club or individual who supports our vision, mission Executive President: Bob St. John and purpose as outlined below and includes benefits such as a subscription to our semi- Vice President: Dave Wharton annual newsletter Cloudburst, monthly updates through our FMCBC E-News, and access to Secretary: Mack Skinner Third-Party Liability insurance. -

The Use of Alpine Habitats by Migratory Birds in B.C. Parks 1998 Summary

The Use of Alpine Habitats by Migratory Birds in B.C. Parks 1998 Summary Dr. Kathy Martin Centre for Applied Conservation Biology University of British Columbia Forest Sciences Centre University of British Columbia 2424 Main Mall Vancouver, B.C. V6T 1Z4 phone: (604) 822-9695 fax: (604) 822-9102 email: [email protected] Report compiled by: Steve Ogle Cite as: Martin, K. and S. Ogle. 2000. The Use of Alpine Habitats by Migratory Birds in B.C. Parks: 1998 Summary. Unpublished report, Department of Forest Sciences, Univ. of British Columbia and Canadian Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region. 15 p. http://www.forestry.ubc.ca/alpine/docs/alpmig-2.pdf Background and objectives Our investigation is aimed at determining the relative importance of high-elevation habitats to migratory birds in southwestern British Columbia. Both altitudinal (moving upslope) and latitudinal (traveling south) migrant birds are thought to take advantage of abundant resources that occur in alpine habitats during late summer. This seasonal resource may play a significant role in the survival of many individuals of various species. Although many high-elevation habitats are protected in parks and reserves, climatologists believe that these areas could be adversely influenced by even minor climatic changes. In southwestern B.C., alpine areas form the headwaters of all major watersheds, and monitoring of avian abundance may help to model the health of downstream water resources. In general, little is known about the ecology of alpine and sub-alpine habitats and we hope that this study will broaden the understanding and awareness of these fragile ecosystems. -

Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation

Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, and Nanoose First Nation COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: Strathcona Forestry Consulting GIS mapping: Madrone Environmental Services Ltd. November 2010 Strathcona Forestry Consulting pg 1 Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation Lantzville Nanoose Bay Nanoose First Nation Community Wildfire Protection Plan Prepared for: Regional District of Nanaimo Submitted by: Strathcona Forestry Consulting GIS Mapping by: Madrone Environmental Consulting Ltd. November 2010 This Community Wildfire Protection Plan was developed in partnership with: Ministry of Forests and Range Union of British Columbia Municipalities Regional District of Nanaimo Nanoose First Nation Lantzville Fire Rescue District of Lantzville Nanoose Bay Fire Department District of Nanoose Bay CF Maritime Experimental and Test Ranges – Nanoose Range Fire Detachment Administration Preparation: RPF Name (Printed) RPF Signature Date: ___________________ RPF No: _________ Strathcona Forestry Consulting pg 2 Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 INTERFACE COMMUNITIES 4 1.2 COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN 7 1.3 LANTZVILLE, NANOOSE BAY, NANOOSE FIRST NATION CWPP 9 2.0 THE SETTING 10 2.1 COMMUNITY PROFILES 10 2.2 LANTZVILLE 11 2.3 NANOOSE BAY 15 2.4 NANOOSE FIRST NATION 18 3.0 BIOPHYSICAL DESCRIPTION 20 3.1 CLIMATE 20 3.2 PHYSIOGRAPHIC FEATURES -

To Read an Excerpt from Claiming the Land

CONTENTS S List of Illustrations / ix Preface / xi INTRODUCTION Fraser River Fever on the Pacific Slope of North America / 1 CHAPTER 1 Prophetic Patterns: The Search for a New El Dorado / 13 CHAPTER 2 The Fur Trade World / 36 CHAPTER 3 The Californian World / 62 CHAPTER 4 The British World / 107 CHAPTER 5 Fortunes Foretold: The Fraser River War / 144 CHAPTER 6 Mapping the New El Dorado / 187 CHAPTER 7 Inventing Canada from West to East / 213 CONCLUSION “The River Bears South” / 238 Acknowledgements / 247 Appendices / 249 Notes / 267 Bibliography / 351 About the Author / 393 Index / 395 PREFACE S As a fifth-generation British Columbian, I have always been fascinated by the stories of my ancestors who chased “the golden butterfly” to California in 1849. Then in 1858 — with news of rich gold discoveries on the Fraser River — they scrambled to be among the first arrivals in British Columbia, the New El Dorado of the north. To our family this was “British California,” part of a natural north-south world found west of the Rocky Mountains, with Vancouver Island the Gibraltar-like fortress of the North Pacific. Today, the descendants of our gold rush ancestors can be found throughout this larger Pacific Slope region of which this history is such a part. My early curiosity was significantly moved by these family tales of adventure, my great-great-great Uncle William having acted as fore- man on many of the well-known roadways of the colonial period: the Dewdney and Big Bend gold rush trails, and the most arduous section of the Cariboo Wagon Road that traversed and tunnelled through the infamous Black Canyon (confronted by Simon Fraser just a little over 50 years earlier). -

Journals of the Legislative Assembly O� ��E ��O�I�Ce O� ��I�Is� Co�Um�Ia

JOURNALS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY O E OICE O IIS COUMIA d, Otbr , 2 EE OCOCK .M. This being the first day of the first meeting of the Thirtieth Parliament or Legislative Assembly of the Province of British Columbia for the dispatch of busi- ness, pursuant to a Proclamation of Colonel the Honourable O R. NICHOLSON, P.C., 0.B.E., Q.C., LL.D., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province, dated the 21st day of September 1972, the members took their seats, after having taken the prescribed oath and having signed the Parliamentary Roll. Colonel the Honourable JOHN R. NICHOLSON, P.C., 0.B.E., QC., LL.D., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province, having entered the House, took his seat on the Throne. The Hon. Ernest Hall, Provincial Secretary, said: Members of the Legislative Assembly: I am commanded by His Honour the Lieutenant-Governor to announce that he does not see fit to declare the cause of his summoning you at this time, and will not do so until you have chosen a Speaker to preside over your Honourable Body. His Honour the Lieutenant-Governor hopes to be enabled to declare, during the afternoon, his reasons for calling you together. His Honour was then pleased to retire. Mr. Graham R. Lea, addressing himself to the Clerk, moved, seconded by Mr. Patrick L. McGeer, that Gordon Hudson Dowding, Esquire, member for Burnaby-Edmonds Electoral District, do take the Speaker's chair and preside over the meetings of this Assembly. Mr. Chabot moved, seconded by Mr. Phillips, that Garde B. Gardom, Esquire, second member for Vancouver-Point Grey Electoral District, do take the Speaker's chair and preside over the meetings of this Assembly. -

Reduced Annualreport1972.Pdf

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND CONSERVATION HON. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS, Minister LLOYD BROOKS, Deputy Minister REPORT OF THE Department of Recreation and Conservation containing the reports of the GENERAL ADMINISTRATION, FISH AND WILDLIFE BRANCH, PROVINCIAL PARKS BRANCH, BRITISH COLUMBIA PROVINCIAL MUSEUM, AND COMMERCIAL FISHERIES BRANCH Year Ended December 31 1972 Printed by K. M. MACDONALD, Printer to tbe Queen's Most Excellent Majesty in right of the Province of British Columbia. 1973 \ VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 To Colonel the Honourable JOHN R. NICHOLSON, P.C., O.B.E., Q.C., LLD., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: Herewith I beg respectfully to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS Minister of Recreation and Conservation 1_) VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 The Honourable Robert A. Williams, Minister of Recreation and Conservation. SIR: I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. LLOYD BROOKS Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation CONTENTS PAGE Introduction by the Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation_____________ 7 General Administration_________________________________________________ __ ___________ _____ 9 Fish and Wildlife Branch____________ ___________________ ________________________ _____________________ 13 Provincial Parks Branch________ ______________________________________________ -

Stanley Park Ecological Action Plan

Date: January 10, 2011 TO: Board Members – Vancouver Park Board FROM: General Manager – Parks and Recreation SUBJECT: Stanley Park Ecological Action Plan RECOMMENDATION A. That the Board approve the recommended actions identified in this report and summarized in Appendix E to improve the ecological integrity of Stanley Park in the following five priority areas of concern: Beaver Lake’s rapid infilling; Lost Lagoon’s water quality; invasive plant species; fragmentation of habitat; and Species of Significance. B. That the Board approve a consultancy to develop a vision and implementation strategy for Beaver Lake in 2011 to ensure the lake’s long-term viability, to be funded from the 2011 Capital Budget. POLICY The Park Board’s Strategic Plan 2005 – 2010 includes five strategic directions, one of which is Greening the Park Board. The plan states that that the “preservation and enhancement of the natural environment is a core responsibility of the Park Board" and that the Board “will develop sustainable policies and practices that achieve environmental objectives while meeting the needs of the community”. It includes actions relevant to the ecological integrity of Stanley Park, such as: advocate for a healthy urban environment, integrate sustainability concepts into the design, construction and maintenance of parks, preserve existing native habitat and vegetation and promote and improve natural environments. The Stanley Park Forest Management Plan, approved on June 15, 2009, includes relevant Goals and Management Emphasis Areas. It identifies Wildlife Emphasis Areas, areas of the forest as having high importance to the ecological integrity of the park, and recommends facilitating projects that protect or enhance wildlife and their habitats. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Rare Birds of Vancouver Island: May 1, 2018: 3Rd Edition Compiled by Rick Toochin, Paul Levesque, Jamie Fenneman, and Don Cecile

Rare Birds of Vancouver Island: rd May 1, 2018: 3 Edition Compiled by Rick Toochin, Paul Levesque, Jamie Fenneman, and Don Cecile. Comments? Contact E-Fauna BC Area Covered This is a list of all known, published and unpublished records of casual and accidental species that have been reported on and around Vancouver Island. This list of records covers all of the land mass of Vancouver Island from Cape Scott at the northern most point of Vancouver Island to East Sooke Park which is the southern most point of land on Vancouver Island. The rare bird records found within this document also cover the waters that surround all of Vancouver Island. On the west coast this extends out to the 200 mile limit of what is considered Canadian waters. On the northern part of Vancouver Island this extends up into Queen Charlotte Sound down the Johnstone Strait to the middle of the Strait of Georgia south to the International Boundary and west through the Juan de Fuca Strait following the International Boundary back out to the 200 mile edge. The islands included on this list area includes Triangle Island and the Scott Islands at the northwest tip of the island. The list also includes the islands off the northeast coast of Vancouver Island such as Hope Island, Nigei Island, Hurst Island south to Malcolm Island and Hanson Island. Then the boundary travels south through Johnstone Strait including Sonora Island, Stuart Island, Quadra Island, Maurelle Island, Reed Island, Cortes Island, Martina Island, Hernando Island, Savary Island, Mitlenach Island, Harwood Island, Texada Island and Lasquetti Islands in the northern Strait of Georgia.