Retelling the Nation: Narrating the Nation Through Biopics, Preeti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Movies, Brand Australia and the Marketing of Australian Cosmopolitanism

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2013 Indian movies, brand Australia and the marketing of Australian cosmopolitanism Andrew Hassam University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hassam, Andrew, "Indian movies, brand Australia and the marketing of Australian cosmopolitanism" (2013). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 919. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/919 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Indian movies, brand Australia and the marketing of Australian cosmopolitanism Abstract Indian movies shot overseas have attracted the attention of not only advertising agencies keen to see their clients' brands appearing on-screen, but also government tourism commissions eyeing India's growing middle classes as potential visitors. Australian federal and state governments offer Indian film producers financial incentives to film in Australia, and Australian cities now regularly supply Indian movies with backdrops of upmarket shopping malls, stylish apartments and exclusive restaurants. Yet in helping to project the lifestyle fantasies of India's new middle classes, Australian government agencies are supporting an Indian view of Australia. While this image may attract Indian tourists to Australia, it presumes Australia is culturally White and British, and as a result Australian agencies market an Australian cosmopolitanism defined not in terms of cultural diversity but in terms of the availability of global brands. -

Androcentrism in Indian Sports

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Androcentrism in Indian sports Bijit Das [email protected] Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Sociology Dibrugarh University Dibrugarh, Assam, India 786004 Abstract The personality of every individual concerning caste, creed, religion, gender in India depends on the structures of society. The society acts as a ladder in diffusing stereotypes from generation to generation which becomes a fundamental constructed ideal type for generalizing ideas on what is masculine or feminine. The gynocentric and androcentric division of labor in terms of work gives more potential for females in household works but not as the position of males. This paper is more concentrated on the biases of women in terms of sports and games which are male- dominated throughout the globe. The researcher looks at the growing stereotypes upon Indian sports as portrayed in various Indian cinemas. Content analysis is carried out on the movies Dangal and Chak de India to portray the prejudices shown by the Indian media. A total of five non-fictional sports movies are made in India in the name of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013), Paan Singh Tomar(2012), MS Dhoni: An untold story(2016), Azhar(2016), Sachin: A billion dreams(26 May 2017) are on male sportsperson whereas only two movies are on women, namely Mary Kom (2014), Dangal(2017). This indicates that male preference is more than female in Indian media concerning any sports. The acquaintance of males in every sphere of life is being carried out from ancient to modern societies. This paper will widen the perspectives of not viewing society per media but to the independence and equity of both the sex in every sphere of life. -

Recruiter's Handbook 2020

Recruiter’s Handbook 2020 VISION To create a state-of-the-art institution that sets new standards of world-class education in film, communication and creative arts. MISSION Benchmarking quality, inspiring innovation, encouraging creativity & moulding minds, by leading from the front in the field of film, media and entertainment education. ONE OF THE TEN BEST FILM SCHOOLS IN THE WORLD - THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER Degree & Diploma 5.5 ACRE programmes CAMPUS acceredited by the TISS 1300+ 2200+ STUDENTS Media & Film industry Alumni campus SCHOOL OF EVENT MANAGEMENT Subhash Ghai Founder & Chairman, Whistling Woods International Chairman, Mukta Arts Limited Member, Executive Committee, Film & Television Producers Guild of India Member, United Producers Forum Education Evangelist Karamveer Chakra Awardee Chairman, MESC Subhash Ghai is a globally renowned filmmaker having directed 19 films over a four-decade career, with 14 of them being blockbusters. Recipient of many national and international awards, he has also been honoured by the United States Senate. He has been a former Chairman of the Entertainment Committee of Trade body CII and also a member of FICCI, NASSCOM and TIE Global & its alliances. He has been invited to address various forums and seminars on corporate governance and the growth of Media & Entertainment industry globally and in India. He is presently serving as the Chairman of Media and Entertainment Skills Council (MESC). Message from the Founder & Chairman My journey as a filmmaker in the Media & Entertainment (M&E) industry has been a long and cherished one. Over the years, the one factor that has grounded me and contributed to my success is the basic film education I received from the film institute I studied in, coupled with my strong desire to learn and re-learn from my days as part of the Indian film industry. -

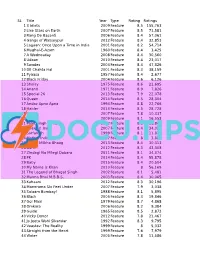

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Rebellion of 1857 Was Doomed to Fail, but the Religious and Cultural Tensions It Inflamed Would Ultimately Topple the British Raj by Ron Soodalter

THE INDIAN REBELLION OF 1857 WAS DOOMED TO FAIL, BUT THE RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL TENSIONS IT INFLAMED WOULD ULTIMATELY TOPPLE THE BRITISH RAJ BY RON SOODALTER On May 9,1857, some 4,000 British soldiers and sepoys—native Indian troops—formed a three-sided hollow square on the parade ground at the Meerut mihtary cantonment, 40 miles northeast of Delhi, to witness punishment. On the fourth side of the square 85 sepoys of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry—Muslims and Hindus, many of them veterans with long years of service—stood at attention as their uniform jackets were stripped from them. The disgraced soldiers, weeping and begging for mercy, were then marched away to imprisonment at hard lahor. The offense for which they had been court-martialed was disobedience—they had refused to load their rifles. or more than 150 years historians percussion cap, bring the hammer to removed from the cartridge, the sides of have maintained that India's First full cock and fire. the bullet should be wetted in the mouth revolt against British rule broke During manufacture the cartridges bejoi e putting it into the barrel; the out at least in part over a gun-—to were coated with beeswax and tallow to saliva will serve the purpose of grease beF precise, the muzzle-loading Pattern protect the powder from the elements, for the time being. 1853 Enfield rifle-musket. Each of the and the bullets were greased to ensure a weapon's paper cartridges contained a proper seal in the barrel. The adjutant- When rumors spread among the precise amount of powder and a .577- general's official 1856 Instruction of caliber Minié ball. -

My Favourite Singers

MY FAVOURITE SINGERS 12 01 01 SAMJHAWAN 17 CHALE CHALO 33 BARSO RE 48 JEENA 63 AY HAIRATHE 79 DIL KYA KARE (SAD) 94 SAAJAN JI GHAR AAYE 108 CHHAP TILAK 123 TUM MILE (ROCK) 138 D SE DANCE ARTIST: ARIJIT SINGH, SHREYA GHOSHAL • ALBUM/FILM: HUMPTY SHARMA KI DULHANIA ARTIST: A. R. RAHMAN, SRINIVAS • ALBUM/FILM: LAGAAN ARTIST: SHREYA GHOSHAL, UDAY MAZUMDAR • ALBUM/FILM: GURU ARTIST: SONU NIGAM, SOWMYA RAOH • ALBUM/FILM: DUM ARTIST: ALKA YAGNIK, HARIHARAN • ALBUM/FILM: GURU ARTIST: KUMAR SANU, ALKA YAGNIK • ALBUM/FILM: DIL KYA KARE ARTIST: KAVITA KRISHNAMURTHY, ALKA YAGNIK, KUMAR SANU ARTIST: KAILASH KHER • ALBUM/FILM: KAILASA JHOOMO RE ARTIST: SHAFQAT AMANAT ALI • ALBUM/FILM: TUM MILE ARTIST: VISHAL DADLANI, SHALMALI KHOLGADE, ANUSHKA MANCHANDA 02 ENNA SONA 18 ROOBAROO 34 KHUSHAMDEED 49 WOH PEHLI BAAR 64 AGAR MAIN KAHOON 80 DEEWANA DIL DEEWANA ALBUM/FILM: KUCH KUCH HOTA HAI 109 CHAANDAN MEIN 124 TERE NAINA ALBUM/FILM: HUMPTY SHARMA KI DULHANIA ARTIST: ARIJIT SINGH • ALBUM/FILM: OK JAANU ARTIST: A. R. RAHMAN, NARESH IYER • ALBUM/FILM: RANG DE BASANTI ARTIST: SHREYA GHOSHAL • ALBUM/FILM: GO GOA GONE ARTIST: SHAAN • ALBUM/FILM: PYAAR MEIN KABHI KABHI ARTIST: ALKA YAGNIK, UDIT NARAYAN • ALBUM/FILM: LAKSHYA ARTIST: UDIT NARAYAN, AMIT KUMAR • ALBUM/FILM: KABHI HAAN KABHI NA 95 MAIN ALBELI ARTIST: KAILASH KHER • ALBUM/FILM: KAILASA CHAANDAN MEIN ARTIST: SHAFQAT AMANAT ALI • ALBUM/FILM: MY NAME IS KHAN 139 VELE 03 GERUA 19 TERE BINA 35 BAHARA 50 TUNE MUJHE PEHCHAANA NAHIN 65 KUCH TO HUA HAI 81 KUCH KUCH HOTA HAI ARTIST: KAVITA KRISHNAMURTHY, SUKHWINDER SINGH • ALBUM/FILM: ZUBEIDAA 110 AA TAYAR HOJA 125 AKHIYAN ARTIST: VISHAL DADLANI, SHEKHAR RAVJIANI • ALBUM/FILM: STUDENT OF THE YEAR ARTIST: ARIJIT SINGH, ANTARA MITRA • ALBUM/FILM: DILWALE ARTIST: A. -

Sacred Freedom

Sacred Freedom The 75th Indian Independence Day is round the corner. We should be grateful to our freedom fighters for giving us our sacred freedom. In last seven decades, India achieved multi-faceted socio- economic progress. India and made great strides and moved forward displaying remarkable progress in the field of agriculture, industry, technology and overall economic development. It is a hard- earned freedom what we Indians are enjoying right now; starting with Mangal Pandey’s sepoy mutiny in 1857, also known as India’s first war of independence. The earliest harbinger of freedom movement could easily have compromised and could have settled for their personal benefits, but they didn’t. They took action and sacrificed their lives. People of India, from different religions, states, communities, castes and socio- economic backgrounds put their heads together and compelled Firangis to leave the subcontinent. Their commitment to free, sovereign and independent India, devoid of personal gratification, is the only reason, that we are living in a free country and are able to achieve and live with our basic human rights. Freedom fighters like Gandhiji, known as ‘Father of the nation’, showed us path to Ahimsa (non-voilence) and Satyagraha, the weapons which are far greater than Himsa (violence). He became the driving force to India’s independence movement. Like his other teachings, it was rooted in the ancient wisdom of India and yet has a resonance in the 21st century and in our daily lives. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel also revered as ‘Iron man of India’, convinced all princely states and united each part of subcontinent to form India and showed us the strength in unity. -

Goldmedal Collaborates with Farhan Akhtar Starer Toofaan

Goldmedal Electricals collaborates with this year’s most-awaited release — Farhan Akhtar starrer TOOFAAN Toofaan is presented by Amazon Prime Video in association with Excel Entertainment and ROMP Pictures. Toofaan is produced by Ritesh Sidhwani, Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra and Farhan Akhtar The film stars Farhan Akhtar, alongside Mrunal Thakur, Paresh Rawal, Supriya Pathak Shah and Hussain Dalal in pivotal roles and is directed by Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra Prime members in India and across 240 countries and territories can stream Toofaan exclusively on Amazon Prime Video starting July 16, 2021 Mumbai, 6th July 2021 – Goldmedal Electricals, a leading home-grown fast moving electrical goods (FMEG) company has entered into a brand association with the upcoming inspirational sports drama, ‘Toofaan’. Presented by Amazon Prime Video in association with Excel Entertainment and ROMP Pictures, Toofaan is an inspiring sports drama produced by Ritesh Sidhwani, Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra and Farhan Akhtar. The film’s high-octane trailer takes us through the journey of a local goon, Ajju Bhai becoming a professional boxer, Aziz Ali. Toofaan is a tale of hope, faith and inner strength fuelled by passion and perseverance. The film will premiere on Amazon Prime Video on 16th July across 240 countries and territories. Goldmedal's rationale behind associating with Toofaan is in line with its passion of making innovative, world-class products that create amazing lifestyles. The main protagonist in the movie perseveres against all odds to follow his passion and thus achieve his goals – it’s the story of an amazing turnaround against insurmountable challenges. Goldmedal is a brand that is passionate about the quality of products it manufactures. -

The Mutiny to Come Faisal Devji

The Mutiny to Come Faisal Devji New Literary History, Volume 40, Number 2, Spring 2009, pp. 411-430 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/nlh.0.0089 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/nlh/summary/v040/40.2.devji.html Access Provided by Oxford University Library Services at 08/09/10 5:55PM GMT The Mutiny to Come Faisal Devji n the spring of 1857, some of the East India Company’s troops in Barrackpore and Berhampore began refusing to follow orders. Ris- Iing against the English in Meerut soon after, these soldiers marched to Delhi, where they placed the powerless Mughal emperor, himself a pensioner of the company, at their head. Spreading across a large portion of northern India, including the cities of Cawnpore and Lucknow, the revolt was eventually put down by men loyal to the British and, by the end of 1858, had been completely stamped out. Apart from constituting the greatest anticolonial rebellion of the nineteenth century, to which Karl Marx, for instance, devoted several substantial essays that compared it to the French Revolution, the Indian Mutiny was immediately recognized as a war unprecedented in its brutality, involving as it did massacres of civilians on both sides and the large-scale destruction of their habitations. And though the mutiny’s casualties were not comparable to those of the roughly contemporaneous Crimean War or the Civil War in America, it remained the most important site of cruelty, horror, and bloodshed for both Englishmen and Indians at least until the First World War. -

Modern India 1857-1972

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Modern India (1857 – 1969) Subject: MODERN INDIA (1857 – 1969) Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Historical background – British rule and its legacies, National movement, Partition and Independence Origins and goals of the Indian National Congress, Formation of the Muslim League Roles played by Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah and the British in the development of the Movement for independence Challenges faced by the Government of India, Making the Constitution, Political, Economic and Social developments from 1950-1990, The Nehru Years – challenges of modernization and diversity, Brief on Indira Gandhi Developments post-1990, Economic liberalization, Rise of sectarianism and caste based politics, Challenges to internal security Foreign Policy: post – Nehru years, Pakistan and Kashmir, Nuclear policy, China and the U. S. Suggested Readings: 1. Ramachandra Guha, Makers of Modern India, Belknap Press 2. Akash Kapur, India Becoming: A Portrait of Life in Modern India, Riverhead Hardcover 3. Bipin Chandra, History Of Modern India, Orient Blackswan 4. Barbara D. Metcalf, Thomas R. Metcalf, A Concise History of Modern India, Cambridge University Press CHAPTER 1 IMPERIALISM, COLONIALISM AND NATIONALISM STRUCTURE Learning objectives Imperialism and colonialism: A theoretical perspective Imperialism: Its effects The rise of national consciousness The revolt of 1857 Colonialism: -

Film Festivals Bridge the Gap Between the Countries : Smita Pant by : INVC Team Published on : 13 Jan, 2016 10:18 PM IST

Film Festivals bridge the gap between the countries : Smita Pant By : INVC Team Published On : 13 Jan, 2016 10:18 PM IST INVC NEWS New Delhi, The Indian Film Festival Vietnam (IFFV) that took place in Vietnam from 18th December-23rd December 2015 concluded in a grand style in Ho Chi Minh City on December 23, 2015. The six-day fest was aimed at bridging the gap between the two entertainment industries in the world – Vietnam and India. According to Consul General of India Ms Smita Pant,” Film Festivals bridge the gap between the countries,we havereceived huge applause from the audience and we are going to soon screen “3 Idiots” again in Ho Chi Minh City. We want to introduce to Vietnamese audiences our best films from the Indian cinema. Entertainment industries of two countries-Vietnam and India can generate over US$5 billion by 2019. “ Eight Indian movies including “3 Idiots,” “Bhaag Milkha Bhaag,” “Paheli,” “Taare Zameen Par,” “Dil Chahta Hai,” “Wake Up Sid,” “Oh My God!” and “Jodhaa Akbar” were screened as part of many activities of the film fest, co-organized by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of Vietnam and the Directorate of Film Festivals under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting of India. Mr. R C Dalal - the co-curator of IFFW says,”A film festival is a celebration of artistic excellence. Film festivals are an eye into another world of cinema; these films take you to a different world. It really expands the horizons and understanding between the two countries. Vietnam has got great locations to offer from film point of view and at the same time, film festival promotes tourism between the two countries.” Many Indian directors have planned to shoot parts of their movies at some locations in Vietnam next year, according to the head of the Consulate General of India in Ho Chi Minh City.