Derrymore Estate (Now Owned by the National Trust) Includes a Rath That Was Planted As a Garden Feature and Adorned with Follies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outdoor Recreation Action Plan for South Armagh (Summary Document) June 2017

Outdoor Recreation Action Plan for South Armagh (Summary Document) June 2017 Prepared by Outdoor Recreation NI on behalf of Newry, Mourne and Down District Council and Ring of Gullion Partnership CONTENTS Figures .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Tables ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Background ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 3. Aim and objectives .................................................................................................................................................. 4 4. Scope ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 4.1 Study boundary .................................................................................................................................................. -

Newry & Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan

Newry & Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan Ulster Wildlife Trust watch Contents Foreword .................................................................................................1 Biodiversity in the Newry and Mourne District ..........................2 Newry and Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan ..4 Our local priority habitats and species ..........................................5 Woodland ..............................................................................................6 Wetlands ..................................................................................................8 Peatlands ...............................................................................................10 Coastal ....................................................................................................12 Marine ....................................................................................................14 Grassland ...............................................................................................16 Gardens and urban greenspace .....................................................18 Local action for Newry and Mourne’s species .........................20 What you can do for Newry and Mourne’s biodiversity ......22 Glossary .................................................................................................24 Acknowledgements ............................................................................24 Published March 2009 Front Cover Images: Mill Bay © Conor McGuinness, -

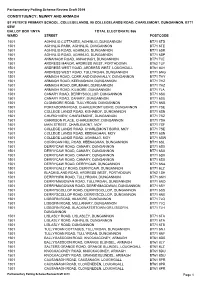

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

58 Farr James Wood

JAMES WOOD EAST DOWN’S LIBERAL MP 4 Journal of Liberal History 58 Spring 2008 JAMES WOOD EAST DOWN’S LIBERAL MP ‘I thought you might he object of our inter- its expression of praise of James est was a thick leather- Wood and the political stand he be interested in this,’ bound book covered took. was the understatement in embossed decora- It reads: from George Whyte tion and measuring Ttwelve inches by fourteen inches Dear Sir of Crossgar, who had in size. The title page, in richly- After your contest at the decorated lettering of gold, red late General Election to remain come across something and green, interwoven with flax Liberal Representative of East of fascinating flowers, read, ‘Address and Pres- Down in the Imperial Parlia- entation to James Wood, Esq., ment, your supporters in that local interest at a Member of Parliament for East Division, and numerous friends Belfast auction. Down, 1902–06 from His Late elsewhere, are anxious to Constituents.’ Another page express to you in tangible form Auctions provide contained a sepia photograph of their admiration for the gen- much television a serious-looking James Wood tlemanly manner in which you in a high collar and cravat, sur- conducted your part of the con- entertainment, but they rounded by a decorated motif tests in the interests of Reform, can also be a valuable of shamrock, flax, roses and Sobriety, Equal Rights and thistles.1 Goodwill among men – as source of local history, In Victorian and Edward- against the successful calumny, ian times, illuminated addresses intemperance, and organised and this find was to were a popular way of expressing violence of your opponents shed new light on an esteem for a person, particularly who have always sought to as a form of recognition for pub- maintain their own private episode in Irish history lic service. -

The Poets Trails and Other Walks a Selection of Routes Through Exceptional Countryside Rich in Folklore, Archaeology, Geology and Wildlife

The Poets Trails and other walks A selection of routes through exceptional countryside rich in folklore, archaeology, geology and wildlife www.ringofgullion.org BELLEEK CAMLOUGH NEWRY Standing A25 Stone Welcome to walks in Derrylechagh Lough the Ring of Gullion Camlough Courtney Cashel Mountain The Ring of Gullion lies within a Mountain Cam Lough region long associated with an Chambered ancient frontier that began with Grave Slieveacarnane Militown Lough the earliest records of man’s Greenon The Long Stone Lough habitation in Ireland. It was along these roads and fields, and over Slievenacappel these hills and mountains, that 4 Killevy 3 1 St Bline’s Church 3 Cúchulainn and the Red Branch B 1 Well 1 B Knights, the O’Neills and 0 3 B O’Hanlons roamed, battled and Slieve Gullion MEIGH died. The area, which has always 1 A Victoria Lock represented a frontier from the A Adventure ancient Iron Age defences of the 2 9 MULLAGHBANE Playground WARRENPOINT Dorsey, through the Anglo- Norman Pale, and latterly the SILVERBRIDGE modern border, is alive with history, scenic beauty and culture. DRUMINTEE JONESBOROUGH Slieve This area reflects the mix of Breac cultures from Neolithic to the FORKHILL CREGGAN Black present, while the rolling Kilnasaggart Mountain Inscribed countryside lends itself to the Stone enjoyment of peaceful walks, excellent fishing and a friendly welcome at every stop. Key to Map Creggan Route Forkhill Route Ballykeel Route Slieve Gullion Route Camlough Route Annahaia Route Glassdrumman Lake Art Mac Cumhaigh’s Headstone Ring of Gullion Way Marked Way 02 | www.ringofguillion.org www.ringofguillion.org | 03 POETS TRAIL – CREGGAN ROUTE POETS TRAIL – CREGGAN ROUTE Did You Know? Creggan graveyard is a truly ecumenical place as members of both Catholic and Protestant denominations still bury in its fragrant clay. -

The Concise Dictionary A-Z

The Concise Dictionary A-Z Helping to explain Who is responsible for the key services in our district. In association with Newry and Mourne District Council www.newryandmourne.gov.uk 1 The Concise Dictionary Foreword from the Mayor Foreword from the Clerk As Mayor of Newry and Mourne, I am delighted We would like to welcome you to the third to have the opportunity to launch this important edition of Newry and Mourne District Council’s document - the Concise Dictionary, as I believe Concise Dictionary. it will be a very useful source of reference for all Within the Newry and Mourne district there our citizens. are a range of statutory and non-statutory In the course of undertaking my duties as organisations responsible for the delivery a local Councillor, I receive many calls from of the key services which impact on all of our citizens regarding services, which are not our daily lives. It is important that we can directly the responsibility of Newry and Mourne access the correct details for these different District Council, and I will certainly use this as organisations and agencies so we can make an information tool to assist me in my work. contact with them. We liaise closely with the many statutory This book has been published to give you and non-statutory organisations within our details of a number of frequently requested district. It is beneficial to everyone that they services, the statutory and non-statutory have joined with us in this publication and I organisations responsible for that service and acknowledge this partnership approach. -

Newspapers Available on Microfilm Adobe

NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE ON MICROFILM TITLE PLACE DATES REF Anti-Union Dublin 1798-1799 MIC/53 Banner of Ulster Belfast 1842-1869 MIC/301 Belfast Citizen Belfast 1886-1887 MIC/601 Belfast Commercial Chronicle Belfast 1813-1815 MIC/447 Belfast Mercury or Freeman’s Chronicle Belfast 1783-1786, 1787 MIC/401 (Later Belfast Evening Post) Belfast Morning News (Later Morning News; Morning News and Examiner; Belfast 1857-1892 MIC/296 incorporated with Irish News, 1892) Belfast Newsletter Belfast 1783 (6 issues) MIC/53 Belfast Newsletter Belfast 1738-1750; 1752-1865 MIC/19 Downpatrick Recorder Downpatrick 1836-1900 MIC/505 (Later Down Recorder) Downshire Protestant Downpatrick 1855-1862 MIC/72 Dublin Builder (Later Irish Builder) Dublin 1859-1899 MIC/302 Enniskillen Chronicle and Erne Packet (Later Fermanagh Mail and Enniskillen Enniskillen 1808-1826; 1831-1833 MIC/431 Chronicle; incorporated with the Impartial reporter 1893) Gordon’s Newry Chronicle and General Newry 1792-1793 MIC/56 Advertiser Guardian and Constitutional Advocate Belfast 1827-1836 MIC/294 Irish Felon Dublin 1848 MIC/53 Irishman Belfast 1819-1825 MIC/402 Larne Monthly Visitor Larne 1839-1863 MIC/130 Lisburn, Hillsborough and Dromore Lisburn 1851 MIC/332/3 Advertiser and Farmers’ Guide 1772-1773; 1776-1796; Londonderry Journal (Derry Journal) Londonderry 1798-1827; 1828-1876; MIC/60 1878-1887 Londonderry Sentinel Londonderry 1829-1919 MIC/278 Lurgan Chronicle and Northern Lurgan 1850-1851 MIC/332/2 Advertiser Lurgan, Portadown and Banbridge Lurgan 1849-1850 MIC/332/1 Advertiser and -

County Report

FOP vl)Ufi , NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE PRICE 85p NET NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE CONTENTS PART 1— EXPLANATORY NOTES AND DEFINITIONS Page Area (hectares) vi Population vi Dwellings vi Private households vii Rooms vii Tenure vii Household amenities viii Cars and garaging ....... viii Non-private establishments ix Usual address ix Age ix Birthplace ix Religion x Economic activity x Presentation conventions xi Administrative divisions xi PART II--TABLES Table Areas for which statistics Page No. Subject of Table are stated 1. Area, Buildings for Habitation and County 1 Population, 1971 2. Population, 1821-1971 ! County 1 3. Population 1966 and 1971, and Intercensal Administrative Areas 1 Changes 4. Acreage, Population, Buildings for Administrative Areas, Habitation and Households District Electoral Divisions 2 and Towns 5. Ages by Single Years, Sex and Marital County 7 Condition 6. Population under 25 years by Individual Administrative Areas 9 Years and 25 years and over by Quinquennial Groups, Sex and Marital Condition 7. Population by Sex, Marital Condition, Area Administrative Areas 18 of Enumeration, Birthplace and whether visitor to Northern Ireland 8. Religions Administrative Areas 22 9. Private dwellings by Type, Households, | Administrative Areas 23 Rooms and Population 10. Dwellings by Tenure and Rooms Administrative Areas 26 11. Private Households by Size, Rooms, Administrative Areas 30 Dwelling type and Population 12. -

Downloaded the Audio Tours

The Ring of Gullion Landscape Conservation Action Plan Newry and Mourne District Council 2/28/2014 Contents The Ring of Gullion Landscape Partnership Board is grateful financial support for this scheme. 2 Contents Contents Executive summary 6 Introduction 9 Plan author 9 Landscape Conservation Action Plan – Scheme Overview 13 Section 1 – Understanding the Ring of Gullion 19 Introduction 19 The Project Boundary 19 Towns and Villages 20 The Landscape Character 30 The Ring of Gullion Landscape 31 Landscape Condition and Sensitivity to Change 32 Ring of Gullion Geodiversity Profile 33 Ring of Gullion Biodiversity Profile 38 The Heritage of the Ring of Gullion 47 Management Information 51 Section 2 – Statement of Significance 53 Introduction 53 Natural Heritage 54 Archaeological and Built Heritage 59 Geological Significance 62 Historical Significance 63 Industrial Heritage 67 Twentieth Century Military Significance 68 3 Contents Cultural and Human Heritage 68 Importance to Local Communities 73 Section 3 – Risks and Opportunities 81 Introduction 81 Urban proximity and development 81 Crime and anti-social behaviour 82 Wildlife 83 Pressures on farming and loss of traditional farming skills 84 Recreational pressure 85 Illegal recreational activity 87 Lack of knowledge and understanding 87 Climate change 88 Audience barriers 89 National/international economic downturn 90 A forgotten heritage and the loss of traditional skills 90 LPS implementation and sustainability 92 Consultations 93 Conclusions from risks and opportunities 93 Section 4 – Aims -

Draft Louth County Development Plan 2021-2027 Planning Ref: FP2020/057 (Please Quote in All Related Correspondence)

Your Ref: Draft Louth County Development Plan 2021-2027 Planning Ref: FP2020/057 (Please quote in all related correspondence) 23 December 2020 Forward Planning Unit, Development Plan Review, Louth County Council, Town Hall, Crowe Street, Dundalk, Co. Louth A91 W20C Via email: [email protected] Re: Notification under Section 12 (1) (b) of the Planning and Development Act, 2000 (as amended) Re: Notice of Preparation of the Draft Louth County Development Plan 2021-2027 A chara I refer to correspondence to the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht on 14th October 2020 received in connection with the above. The Department welcomes the opportunity to input into the preparation of the Louth County Development Plan. Outlined below are heritage-related observations/recommendations co-ordinated by the Development Applications Unit under the stated headings. Archaeology Introduction It is strongly recommended that a Development Plan contains a specific ‘Archaeological Heritage’ Chapter within the plan. This chapter should set out the policies and objectives as recommended below (see specific recommendations). Definition of Archaeology and Archaeological Heritage It is very important that the Development Plan’s archaeological policies and objectives be informed by a clear understanding of the nature of archaeology and the archaeological Aonad na nIarratas ar Fhorbairt Development Applications Unit Oifigí an Rialtais Government Offices Bóthar an Bhaile Nua, Loch Garman, Contae Loch Garman, Y35 AP90 Newtown Road, Wexford, County Wexford, Y35 AP90 heritage, and it is recommended that a statement on this be included in the chapter on archaeological heritage. The following is noted by way of assistance in drafting such text. -

(HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children's Social Work

Northern Ireland Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children’s Social Work Belfast HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 028 90507000 Areas Greater Belfast area Further Contact Details Greater Belfast Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) 110 Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 6HD Website http://www.belfasttrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) South Eastern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001000300 Areas Lisburn, Dunmurry, Moira, Hillsborough, Bangor, Newtownards, Ards Peninsula, Comber, Downpatrick, Newcastle and Ballynahinch Further Contact Details Greater Lisburn Gateway North Down Gateway Team Down Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Team James Street Children’s Services Stewartstown Road Health Newtownards, BT23 4EP 81 Market Street Centre Tel: 028 91818518 Downpatrick, BT30 6LZ 212 Stewartstown Road Fax: 028 90564830 Tel: 028 44613511 Dunmurry Fax: 028 44615734 Belfast, BT17 0FG Tel: 028 90602705 Fax: 028 90629827 Website http://www.setrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) Northern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001234333 Areas Antrim, Carrickfergus, Newtownabbey, Larne, Ballymena, Cookstown, Magherafelt, Ballycastle, Ballymoney, Portrush and Coleraine Further Contact Details Central Gateway Team South Eastern Gateway Team Northern Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Unit 5A, Toome Business The Beeches Coleraine -

Inventory of Closed Mine Waste Facilities in Northern Ireland. Phase 1 Data Collection and Categorisation

Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment Minerals and Waste Programme Commercial Report CR/14/031N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERALS AND WASTE PROGRAMME COMMERCIAL REPORT CR/14/031 N Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment B Palumbo-Roe, K Linley, D Cameron, J Mankelow Contributor/editor T Johnston, MC Cowan The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2014. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290. Keywords Mine waste Directive; Inventory; Northern Ireland. Bibliographical reference B PALUMBO-ROE, K LINLEY, D CAMERON, J MANKELOW. 2014. Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment. British Geological Survey Commercial Report, CR/14/031. 66pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. © NERC 2014. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2014 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS shops at British Geological Survey offices Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com BGS Central Enquiries Desk Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including maps, for consultation.