Ties That Bind Margaret Simons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

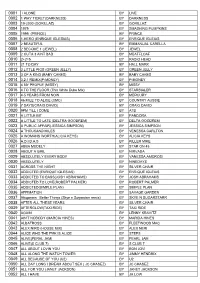

Songs by Artist October 2009 Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions (Hed)Planet Earth 101 Dalmations Wvocal 2 Pistols & Ray J Blackout TH Cruella De Vil DI You Know Me 09 Other Side TH 10cc 2 Play & Thomes Jules & Jucxi “VARIOUS“ Donna SF Careless Whisper MR ROCK N ROLL MEGAMIX ST Dreadlock Holiday 3 2 Unlimited „STANDARD“ I'm Mandy SF No Limit SF AIN'T SHE SWEET ST I'm Not In Love 6 No Limits SF ALL OF ME ST Rubber Bullets 3 20 Fingers BILL BAILEY WON'T YOU PLEASE ST Things We Do For Love, The 3 Short Dick Man 2 COME HOME Wall Street Shuffle SF 20 MILLAS HAS ANYBODY SEEN MY GAL ST We Do For Love SC FLANS 06 HEART OF MY HEART ST 112 21 Demands IF YOU KNEW SUSIE ST Come See Me SC Give Me A Minute TH I'M GONNA SIT RIGHT DOWN AND ST Cupid SC 21 Demands Wvocal WRITE Dance With Me 3 Give Me A Minute TH ME AND MY SHADOW ST It's Over Now 2 21St Century Girls OH YOU BEAUTIFUL DOLL ST Only You SC 21St Century Girls SF RED RED ROBIN ST Peaches & Cream 5 2Pac SING-A-LONG MEDLEY 2 ST Right Here For You PH California Love (Original Version) SC SWANEE ST U Already Know 2 3 Colours Red UNDERNEATH THE ARCHES ST 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day SF WE'LL MEET AGAIN ST Hot & Wet PH 3 Days Grace YOU ARE MY SUNSHINE ST 12 Gauge I Hate Everything About You 2 1 Giant Leap & Maxi, Jazz & Robbie Dunkie Butt SC Just Like You 2 Williams 12 Stones Never Too Late SC My Culture EZ Crash TU Pain CB 10 CC Far Away TH 3 Days Of Grace Donna ZM 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Song Lyrics of the 1950S

Song Lyrics of the 1950s 1951 C’mon a my house by Rosemary Clooney Because of you by Tony Bennett Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give Because of you you candy Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give a There's a song in my heart. you Apple a plum and apricot-a too eh Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house a come on My romance had its start. Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house I’m gonna give a Because of you, you The sun will shine. Figs and dates and grapes and cakes eh The moon and stars will say you're Come on-a my house, my house a come on mine, Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give Forever and never to part. you candy Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give I only live for your love and your kiss. you everything It's paradise to be near you like this. Because of you, (instrumental interlude) My life is now worthwhile, And I can smile, Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give you Christmas tree Because of you. Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give you Because of you, Marriage ring and a pomegranate too ah There's a song in my heart. -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

"Weird Al" Yankovic

"Weird Al" Yankovic - Ebay Abba - Take A Chance On Me `M` - Pop Muzik Abba - The Name Of The Game 10cc - The Things We Do For Love Abba - The Winner Takes It All 10cc - Wall Street Shuffle Abba - Waterloo 1927 - Compulsory Hero ABC - Poison Arrow 1927 - If I Could ABC - When Smokey Sings 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Long Way To The Top 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Thunderstruck 30h!3 - Don't Trust Me Ac Dc - You Shook Me All Night Long 3Oh!3 feat. Katy Perry - Starstrukk AC/DC - Rocker 5 Star - Rain Or Shine Ac/dc - Back In Black 50 Cent - Candy Shop AC/DC - For Those About To Rock 50 Cent - Just A Lil' Bit AC/DC - Heatseeker A.R. Rahman Feat. The Pussycat Dolls - Jai Ho! (You AC/DC - Hell's Bells Are My Destiny) AC/DC - Let There Be Rock Aaliyah - Try Again AC/DC - Thunderstruck Abba - Chiquitita AC-DC - It's A Long Way To The Top Abba - Dancing Queen Adam Faith - The Time Has Come Abba - Does Your Mother Know Adamski - Killer Abba - Fernando Adrian Zmed (Grease 2) - Prowlin' Abba - Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) Adventures Of Stevie V - Dirty Cash Abba - Knowing Me, Knowing You Aerosmith - Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Abba - Mamma Mia Aerosmith - Love In An Elevator Abba - Super Trouper Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion A-Ha - Cry Wolf Alanis Morissette - Not The Doctor A-Ha - Touchy Alanis Morissette - You Oughta Know A-Ha - Hunting High & Low Alanis Morrisette - I see Right Through You A-Ha - The Sun Always Shines On TV Alarm - 68 Guns Air Supply - All Out Of Love Albert Hammond - Free Electric Band -

Rosary Hill Reach out Part II: Community Action Corps

Rosary Hill Reach Out Part II: Community Action Corps by MARIE FORTUNA “You can’t explain wheel-chair Dr. John Starkey nodded about all kinds of human prob strengths to help others, the at the Veteran’s Administration dancing. You’d have to see it. understandingly. “As a kind of lems. Kept the whole class talk world would be a happier place.” Hospital seeks students to feed Thursday afternoons the patients middleman between volunteers ing on that record for the total patients, visit them, lead a com themselves create the dances. and agencies they serve, I ’ve class period,” said sophomore Brian McQueen practice munity sing-a-long,” 'said Dr. Tuesdays they teach it to us. To seen how students have started Bri^n McQueen. teaches at Heim Elementary. Starkey. Angela Kell«*, Virginia Ventura, out frightened of what they don’t He’s busy. Pat Weichsel resident Pat Cowles, Linda Stone and know,” he said. ‘«‘Once they try Brian teaches C.C.D. classes to assistant, volunteer for Project Erie County Detention Home me,” said Pat Weichsel, student it,” he continued, “they find they about 18 seventh graders at Care (as a requirement for her looks for companions and helpers coordinator of the Campus are rewarded.” Saints Peter and Paul School in community psychology course) with the recreation programs for Ministry sponsored Community Williamsville. He has been help says, “Tim eis more of a problem boys $nd girls age 8 to 16 years Action Corps. - “Working for the first time ing children since he himself was than anything else. I don’t really who are awaiting court proceed with persons who have physical 14 years old. -

Turn up the Radio (Explicit)

(Don't) Give Hate A Chance - Jamiroquai 5 Seconds Of Summer - Girls Talk Boys (Karaoke) (Explicit) Icona Pop - I Love It 5 Seconds Of Summer - Hey Everybody! (Explicit) Madonna - Turn Up The Radio 5 Seconds Of Summer - She Looks So Perfect (Explicit) Nicki Minaj - Pound The Alarm 5 Seconds Of Summer - She's Kinda Hot (Explicit) Rita Ora ft Tinie Tempah - RIP 5 Years Time - Noah and The Whale (Explicit) Wiley ft Ms D - Heatwave 6 Of 1 Thing - Craig David (Let me be your) teddy bear - Elvis Presley 7 Things - Miley Cyrus 1 2 Step - Ciara 99 Luft Balloons - Nena 1 plus 1 - beyonce 99 Souls ft Destiny’s Child & Brandy - The Girl Is Mine 1000 Stars - Natalie Bassingthwaighte 99 Times - Kate Voegele 11. HAIM - Want You Back a better woman - beccy cole 12. Demi Lovato - Sorry Not Sorry a boy named sue - Johnny Cash 13 - Suspicious Minds - Dwight Yoakam A Great Big World ft Christina Aguilera - Say Something 13. Macklemore ft Skylar Grey - Glorious A Hard Day's Night - The Beatles 1973 - James Blunt A Little Bit More - 911 (Karaoke) 1979 - good charlotte A Little Further North - graeme conners 1983 - neon trees A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson (Karaoke) 1999 - Prince a pub with no beer - slim dusty.mpg 2 Hearts - Kylie a public affair - jessica simpson 20 Good Reasons - Thirsty Merc.mpg a teenager in love - dion and the belmonts 2012 - Jay Sean ft Miniaj A Thousand Miles - Vanessa Carlton (Karaoke) 21 Guns - Greenday a thousand years - christina perri 21st Century Breakdown - Green Day A Trak ft Jamie Lidell - We All Fall Down 21st century -

BULLYPROOF™ Shields

BULLY PROOF SHIELD page 1 The Legend of the BULLYPROOF™ Shields A Rap'n Roll OPERA by Arthur Kanegis [email protected] www.bullyproof.org Future Wave, Inc. is a not-for-profit Educational organization, supported by tax-deductible donations. © 1986 - 2008 Arthur Kanegis © 1986 - 1996 Arthur Kanegis, Future Wave, Inc. BULLY PROOF SHIELD page 2 The legend of the B U L L Y P R O O F™ Shields A series of shields stretch across the valance above the stage each adorned with its own animal spirit: Bear, Unicorn, Lynx, Lion, Yak, Porpoise, Raven, Otter, Owl and Fox. Around the Shields are the letters: "B.U.L.L.Y. P.R.O.O.F." PROLOGUE: Before the curtain opens, "Pops," an old stage hand, arranges a puzzle on a table, perhaps made of a cable- spool or an old crate . It is by a small park bench, shaded by a large prop tree at the corner of stage right. Anxiously looking around, he addresses the audience. POPS (ad lib, sounding like a real announcement) Excuse me folks. I'm sorry about this, but could you please check around your seats -- this puzzle -- it's a prop for the final scene -- we're missing a piece. It looks like this -- (He picks up a couple of puzzle pieces from a large cable-spool table.) Could be back that way. (He points; audience shuffles around looking.) Or maybe by one of the aisle seats over there.. Might be a red piece. (Examines a puzzle piece) Or maybe yellow. (Shuffles through puzzle pieces) Black? White? It's really crucial.. -

Moments with Jesus

Moments with Jesus Janet Eriksson Moments with Jesus 2 Copyright © 2007 by Janet Eriksson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any way by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise – without the prior permission of the author and publisher. Scripture quotations in this book are from several translations of the Bible: AMP – Amplified Bible CEV – Contemporary English Version NIV – New International Version NKJV – New King James Version NLT – New Living Translation and The Message Bible E-book cover by Mike Smith Copyright © 2007 by Janet Eriksson Moments with Jesus 3 Scripture quotations taken from AMPLIFIED BIBLE, Copyright © 1954, 1958, 1962, 1964, 1965, 1987 by The Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. (www.Lockman.org) Scripture quotations taken from the Contemporary English Version, copyright © 1991 by American Bible Society. Scripture taken from THE MESSAGE. Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Scripture taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. Scripture taken from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, -

We Want More

GOT ISSUES 1 For laid back lifestylers... with a sense of humour 2017 WE WANT MORE Festivals are in a constant state of A half-century later, it’s not just bellbottoms and wanderlust and desire for unique and memory-making evolution, there are now literally hundreds marijuana anymore. Music festivals have evolved into moments – the world is now literally your glittering, of them all over the country and they have a booming multimillion-pound business. But why is it flower-crown-filled oyster! It seems many of us no that so many of us time and time again clear an entire longer have the ‘Woodstock mentality’ and are not up gone from just being a place where you weekend to spend it camping in a foreign town with for pitching our dodgy tents in the rain to hear our watch bands in a field, to an entire four thousands of strangers? favourite band and roughing it anymore, so what do day immersive experience. we want from our festivals? We are craving and chasing experiences over It has been 47 years since Generation X dressed in belongings more than ever before and what better suede hippie vests and flower crowns and gathered at place than in a fairytale haze of escapism in the the firstPilton Pop, Blues & Folk Festival (now more middle of the British countryside…or further afield if commonly known as one of the best festivals in the you really want to live out those hedonistic dreams. world –Glastonbury!), for 1 night of music and peace. Festivals are having to work harder to satisfy our Single-eState gift S S traight from the farmer | cha S ediS tillery.co.uk 2 2017 2017 3 What’s cookin One thing we do know is that festi- joy of spontaneity and is both designed and built by 60 Seconds food is fast becoming just as central teams of emerging artists, architects and musicians; all good lookin’ to the experience as the music.