BEJS 8.1 Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

A Guide to Bangladesh a Fulbright Experience

A Guide to Bangladesh A Fulbright Experience The American Center U.S. Embassy Annex J Block, Progoti Sharoni Baridhara, Dhaka 1212 (opposite the U.S. Embassy) Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8855500-22 Fax: 88-02-9881677 Contact Information Location of the Public Affairs Office: The American Center U.S. Embassy Annex J Block, Progoti Sharoni Baridhara, Dhaka 1212 (Opposite the U.S.Embassy And Next to Notun Bazar) Phone: Number: 8855500-22 Calling From Overseas To Country Code: (880) Dhaka City Code: (2) + Number Points of First Contact for Inquiries (at The American Center): Cultural Affairs Specialist Shaheen Khan Email: [email protected] Work phone – 8855500-22, Ext. 2811 Cell Phone – 01713-043-749 Cultural Affairs Officer for Education and Exchange Ryan G. Bradeen Email: [email protected] Work phone – 8855500-22, ext. 2805 Cell phone – 01730013982 Cultural Affairs Assistant Raihana Sultana E-mail: [email protected] Work phone: 8855500-22, Ext. 2816 Cell phone – 01713-243852 Location of the United States Embassy: U.S. Embassy Madani Avenue Baridhara, Dhaka, Bangladesh Phone: 885-5500 Website: http://dhaka.usembssy.gov American Citizen Services: located in the Consular Section of the U.S. Embassy. Drop-in hours are Sunday through Thursday, 1:00 – 4:00 pm After-hours Emergency: call (2) 882-3805 Congratulations on receiving the Fulbright grant! We look forward to welcoming you to Bangladesh soon. During your stay in Bangladesh it is important that you maintain a relationship with the U.S. Mission in order to successfully participate in the program. This involves close contact with The American Center. -

5. from Janapadas to Empire

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 5 Notes FROM JANAPADAS TO EMPIRE In the last chapter we studied how later Vedic people started agriculture in the Ganga basin and settled down in permanent villages. In this chapter, we will discuss how increased agricultural activity and settled life led to the rise of sixteen Mahajanapadas (large territorial states) in north India in sixth century BC. We will also examine the factors, which enabled Magadh one of these states to defeat all others to rise to the status of an empire later under the Mauryas. The Mauryan period was one of great economic and cultural progress. However, the Mauryan Empire collapsed within fifty years of the death of Ashoka. We will analyse the factors responsible for this decline. This period (6th century BC) is also known for the rise of many new religions like Buddhism and Jainism. We will be looking at the factors responsible for the emer- gence of these religions and also inform you about their main doctrines. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to explain the material and social factors (e.g. growth of agriculture and new social classes), which became the basis for the rise of Mahajanapada and the new religions in the sixth century BC; analyse the doctrine, patronage, spread and impact of Buddhism and Jainism; trace the growth of Indian polity from smaller states to empires and list the six- teen Mahajanapadas; examine the role of Ashoka in the consolidation of the empire through his policy of Dhamma; recognise the main features– administration, economy, society and art under the Mauryas and Identify the causes of the decline of the Mauryan empire. -

Primary Education Finance for Equity and Quality an Analysis of Past Success and Future Options in Bangladesh

WORKING PAPER 3 | SEPTEMBER 2014 BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES PRIMARY EDUCATION FINANCE FOR EQUITY AND QUALITY AN ANALYSIS OF PAST SUCCESS AND FUTURE OPTIONS IN BANGLADESH LIESBET STEER, FAZLE RABBANI AND ADAM PARKER Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES This working paper series is dedicated to the memory of Brooke Shearer (1950-2009), a loyal friend of the Brookings Institution and a respected journalist, government official and non-governmental leader. This series focuses on global poverty and development issues related to Brooke Shearer’s work, including: women’s empowerment, reconstruction in Afghanistan, HIV/AIDS education and health in developing countries. Global Economy and Development at Brookings is honored to carry this working paper series in her name. Liesbet Steer is a fellow at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Fazle Rabbani is an education adviser at the Department for International Development in Bangladesh. Adam Parker is a research assistant at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the many people who have helped shape this paper at various stages of the research process. We are grateful to Kevin Watkins, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the executive director of the Overseas Development Institute, for initiating this paper, building on his earlier research on Kenya. Both studies are part of a larger work program on equity and education financing in these and other countries at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Selim Raihan and his team at Dhaka University provided the updated methodology for the EDI analysis that was used in this paper. -

Volume 89 Number 1 March 2020 V Olume 89 Number 1 March 2020

Volume 89 Volume Number 1 March 2020 Volume 89 Number 1 March 2020 Historical Society of the Episcopal Church Benefactors ($500 or more) President Dr. F. W. Gerbracht, Jr. Wantagh, NY Robyn M. Neville, St. Mark’s School, Fort Lauderdale, Florida William H. Gleason Wheat Ridge, CO 1st Vice President The Rev. Dr. Thomas P. Mulvey, Jr. Hingham, MA J. Michael Utzinger, Hampden-Sydney College Mr. Matthew P. Payne Appleton, WI 2nd Vice President The Rev. Dr. Warren C. Platt New York, NY Robert W. Prichard, Virginia Theological Seminary The Rev. Dr. Robert W. Prichard Alexandria, VA Secretary Pamela Cochran, Loyola University Maryland The Rev. Dr. Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr. Warwick, RI Treasurer Mrs. Susan L. Stonesifer Silver Spring, MD Bob Panfil, Diocese of Virginia Director of Operations Matthew P. Payne, Diocese of Fond du Lac Patrons ($250-$499) [email protected] Mr. Herschel “Vince” Anderson Tempe, AZ Anglican and Episcopal History The Rev. Cn. Robert G. Carroon, PhD Hartford, CT Dr. Mary S. Donovan Highlands Ranch, CO Editor-in-Chief The Rev. Cn. Nancy R. Holland San Diego, CA Edward L. Bond, Natchez, Mississippi The John F. Woolverton Editor of Anglican and Episcopal History Ms. Edna Johnston Richmond, VA [email protected] The Rev. Stephen A. Little Santa Rosa, CA Church Review Editor Richard Mahfood Bay Harbor, FL J. Barrington Bates, Prof. Frederick V. Mills, Sr. La Grange, GA Diocese of Newark [email protected] The Rev. Robert G. Trache Fort Lauderdale, FL Book Review Editor The Rev. Dr. Brian K. Wilbert Cleveland, OH Sheryl A. Kujawa-Holbrook, Claremont School of Theology [email protected] Anglican and Episcopal History (ISSN 0896-8039) is published quarterly (March, June, September, and Sustaining ($100-$499) December) by the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church, PO Box 1301, Appleton, WI 54912-1301 Christopher H. -

Buddhist Discussion Centre (Upwey) Ltd. 33 Brooking St

Buddhist Discussion Centre (Upwey) Ltd. 33 Brooking St. Upwey 3158 Victoria Australia. Telephone 754 3334. (Incorporated in Victoria) NEWSLETTER N0. 11 MARCH 1983 REGISTERED BY AUSTRALIA POST PUBLICATION NO. VAR 3103 ISSN 0818-8254 Inauguration of 1000th Birth Anniversary of Atisa Dipankar Srijnan - Dhaka, Bangladesh,1983. Chief Martial Law Administrator, (C.M.L.A.) Lt. Gen. H. M. Ershad inaugurated the Week-long programme commencing on 26th February, 1983. A full report of this event appeared in the Bangladesh Observer, 20th February, 1983, at Page 1, under the heading "All Religions enjoy equal rights". The C.M.L.A. said it was a matter of great pride that Atisa Dipankar Srijnan had established Bangladesh in the comity of nations an honourable position by his unique contributions in the field of knowledge. Therefore, Dipankar is not only the asset and pride of the Buddhist community; rather he is the pride of Bangladesh and an asset for the whole nation. The C.M.L.A. hoped that the people being imbibed with the ideals of sacrifice, patriotism, friendship and love of mankind of Atisa Dipankar would take part in the greater struggle of building the nation. He called upon the participating delegates to carry with them the message of peace, fraternity, brotherhood, love and non-violence from the people of Bangladesh to the people of their respective countries. Besides Bangladesh, about 50 delegates from about 20 countries took part in the celebration. John D. Hughes, Director of B.D.C. (Upwey), representing Australia at the Conference, would like to express his sincere gratitude to the C.M.L.A. -

Revisit to Dhaka University As the Symbol of Bengal Partition Sowmit Chandra Chanda Dr

Academic Ramification in Colonial India: Revisit to Dhaka University as the Symbol of Bengal Partition Sowmit Chandra Chanda Dr. Neerja A. Gupta PhD Research Scholar under Dr. Neerja A. Director & Coordinator, Department of Gupta, Department of Diaspora and Diaspora and Migration Studies, SAP, Migration Studies, SAP, Gujarat Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, India. University, Ahmedabad, India. Abstract: It has been almost hundred years since University of Dhaka was established back in 1921. It was the 13th University built in India under the Colonial rule. It was that like of dream comes true object for those people who lived in the eastern part of Indian Sub-continent under Bengal presidency in the British period. But when the Bengal partition came into act in 1905, people from the new province of East Bengal and Assam were expecting a faster move from the government to establish a university in their capital city. But, with in 6 years, the partition was annulled. The people from the eastern part was very much disappointed for that, but they never left that demand to have a university in Dhaka. After some several reports and commissions the university was formed at last. But, in 1923, in the first convocation of the university, the chancellor Lord Lytton said this university was given to East Bengal as a ‘splendid Imperial compensation’. Which turns our attention to write this paper. If the statement of Lytton was true and honest, then certainly Dhaka University stands as the foremost symbol of both the Bengal Partition in the academic ramification. Key Words: Partition, Bengal Partition, Colony, Colonial Power, Curzon, University, Dhaka University etc. -

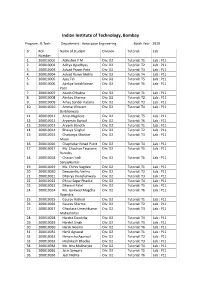

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Challenges of Islamic Da'wah in Bangladesh: the Christian

IIUC STUDIES ISSN 1813-7733 Vol. – 4, December 2007 Published in April 2008 (p 87-108) Challenges of Islamic Da‘wah in Bangladesh: The Christian Missions and Their Evangelization Dr. Md. Yousuf Ali∗ Abu Sadat Nurullah∗∗ Abstract: Although Bangladesh is the second largest Muslim populated country in the world, there are several challenges of Islamic da‘wah here. The Christian mission, taking the opportunity of people’s poverty and distress, is evangelizing them through financial assistance and other means. The rapidly increasing number of conversion to Christianity among the tribal population is alarming. The missionary activities are spreading around the country, chiefly in the intellectual arena, in educational institutions, and in other aspects of life. The influence of it on the culture, education, religion and lifestyle of people results into converting people to the Christian ideology. Particularly the young generations are inclining towards this lucrative dogma of the new age. Media, both print and electronic, are propagating and claiming the banning of the da‘wah movement. In these situation, the Islamic da‘wah movements require to explore and implement new methodology to face the enormous challenges to prevent Bangladesh from becoming a Christian country in future. Keywords: Islamic da‘wah, Christian mission, and evangelization. Introduction: Bangladesh has the fourth largest concentration of Muslim populations in the world with a population of about 140 billion, of which 88 percent are Muslims. However, majority of the population (74 percent according to 2001 census) reside in rural area with lower economic condition and lowest standards of living. In fact, about half of the ∗ Assistant Professor, Faculty of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, IIUM, Malaysia ∗∗ Student Department of Sociology and Anthropology, International Islamic University Malaysia IIUC Studies, Vol. -

Reforming the Education System in Bangladesh: Reckoning a Knowledge-Based Society

www.sciedu.ca/wje World Journal of Education Vol. 4, No. 4; 2014 Reforming the Education System in Bangladesh: Reckoning a Knowledge-based Society Md. Nasir Uddin Khan1, Ebney Ayaj Rana2,* & Md. Reazul Haque3 1Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Bangladesh 2Unnayan Onneshan-A Center for Research and Action on Development based in Dhaka, Bangladesh 3Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh *Corresponding author: Unnayan Onneshan, 16/2, Indira Road, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh. Tel: 880-172-505-2815. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 15, 2014 Accepted: June 3, 2014 Online Published: June 25, 2014 doi:10.5430/wje.v4n4p1 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/wje.v4n4p1 Abstract Education renders people with certain capabilities that prepare them to contribute to the social and economic development of the nation. Such capabilities turn them into human capital which, according to development economists, raises productivity when increased. Following an exhaustive review of literature on education research, this paper, however, aims at exploring the effectiveness of Bangladesh’s present education system in delivering quality education as well as reckoning the prospect of establishing a knowledge-based society in the nation. This paper, being qualitative in nature, reveals that the nation has achieved an exemplary success in primary education as regards increased enrolment rate, while the enrolment rate is not satisfactory in secondary schooling and the tertiary education is expanding. However, the quality of education imparted at all the primary, secondary and tertiary levels is not up to the mark to create a strong human capital and reckon the prospect of knowledge-based society in the country. -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993.