Identification and Evaluation of U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Army Was Already Upset About Its Losses from Deep Personnel and White House Photo Via National Archives Budget Cuts When Gen

National Park Service photo by Abbie Rowe By John T. Correll US Army was already upset about its losses from deep personnel and White House photo via National Archives budget cuts when Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor arrived as the new Chief of Defense Technical Information Center photo Staff in June 1955. Army strength was down by almost a third since the Korean War and the Army share of the budget was dropping steadily. These reductions were the result of the “New Look” defense program, introduced in 1953 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the “Massive Retaliation” strategy that went with it. New Look was focused on the threat of Soviet military power, putting greater reliance on strategic airpower and nuclear weapons and less emphasis on the kind of wars the Army fought. US planning was based on the standard of general war; the limited conflict in Korea was regarded as an aberration. If for some reason another small or limited war had to be fought, the US armed forces, organized and equipped for general war, would handle it as a “lesser included contingency.” New Look—so called because Eisenhower had ordered a “new fresh survey of our military capabilities”—was driven by the belief that adequate security was possible at lower cost, especially if general purpose forces overseas were thinned out. Another factor was the recognition that NATO could not match the con- ventional forces of the Soviet Union, which had 175 divisions—30 of them in Europe—and 6,000 aircraft based forward. So in 1952, the US and its allies had adopted a strategy centered on a nuclear response to attack. -

Chapter 7 the Enduring Hopi

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln HOPI NATION: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law History, Department of September 2008 Chapter 7 The Enduring Hopi Peter Iverson Arizona State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/hopination Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Iverson, Peter, "Chapter 7 The Enduring Hopi" (2008). HOPI NATION: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law. 16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/hopination/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in HOPI NATION: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CHAPTER 7 The Enduring Hopi Peter Iverson “What then is the meaning of the tricentennial observance? It is a reaffirmation of continuity and hope for the collective Hopi future.” The Hopi world is centered on and around three mesas in northeastern Arizona named First, Sec- ond, and Third. It is at first glance a harsh and rugged land, not always pleasing to the untrained eye. Prosperity here can only be realized with patience, determination, and a belief in tomorrow.1 For over 400 years, the Hopis have confronted the incursion of outside non-Indian societies. The Spanish entered Hopi country as early as 1540. Then part of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s explor- ing party invaded the area with characteristic boldness and superciliousness. About twenty Spaniards, including a Franciscan missionary, confronted some of the people who resided in the seven villages that now comprise the Hopi domain, and under the leadership of Pedro de Tovar, the Spanish over- came Hopi resistance, severely damaging the village of Kawaiokuh, and winning unwilling surrender. -

Joint Land Use Study

Fairbanks North Star Borough Joint Land Use Study United States Army, Fort Wainwright United States Air Force, Eielson Air Force Base Fairbanks North Star Borough, Planning Department July 2006 Produced by ASCG Incorporated of Alaska Fairbanks North Star Borough Joint Land Use Study Fairbanks Joint Land Use Study This study was prepared under contract with Fairbanks North Star Borough with financial support from the Office of Economic Adjustment, Department of Defense. The content reflects the views of Fairbanks North Star Borough and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Office of Economic Adjustment. Historical Hangar, Fort Wainwright Army Base Eielson Air Force Base i Fairbanks North Star Borough Joint Land Use Study Table of Contents 1.0 Study Purpose and Process................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.2 Study Objectives ............................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Planning Area................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Participating Stakeholders.............................................................................................. 4 1.5 Public Participation........................................................................................................ 5 1.6 Issue Identification........................................................................................................ -

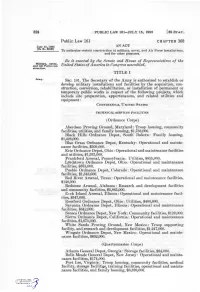

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

Armor, July-August 1993 Edition

It‘s always inspiring for me to discover how an Army, and as a nation. And it is in the many people outside of active duty, national spirit of finding a better way that we feature guard, and reservists like to talk tanks. I can articles on call for fire, field trains security, be on-post, off-post, or at the post office, and and maneuver sketches among others. The once people find out what I do, they can’t historical articles herein provide balance and wait to share their views on armored warfare help us quantify our lessons learned. The or the latest in combat vehicle development. overview on Yugoslavia will set the scene for Sometimes their comments lead to a story for what promises to be a benchmark story com- ARMOR, often times not, but I always come ing in the September-October ARMOR - an away from the discussion edified. I’ve been in eyewitness to a tank battle in the Balkans. this job a year now, and I’ve heard every- So, we martial descendants of St. George thing from, “We need to up-gun the AI,” to keep sharpening our sword and polishing our “I’ve got this idea for how to armor as we await the next make a tank float on a challenge. And while there cushion of air ...” is no hunger for battle in Some of those notions the eyes of those who have about tank design crystal- truly seen it, there is a glint ized recently with our Tank of certainty that it will come Design Contest, sponsored nonetheless. -

Historian J Michael Cobb Shares Stories and Plans

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2019 Contact: Leslie Baker, 757/728-5316 [email protected] Seamus McGrann, 757/727-6841 [email protected] Historian J Michael Cobb Shares Stories and Plans for Renovation of Fort Wool at the Hampton History Museum on August 5 HAMPTON, Va -Author, historian and former Hampton History Museum curator J Michael Cobb shares the fascinating story of Fort Wool, its history, and what lies ahead for the future of the venerable fortress, as part of the Hampton History Museum’s Port Hampton Lecture Series on Monday, August 5, 2019 7:00 p.m.-8:00 p.m. A familiar site to commuters crossing the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel, Fort Wool, originally named Fort Calhoun, has been a patriotic symbol of freedom since its construction in 1819. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, Fort Wool is a visible landmark at the gateway to Hampton Roads. Like Fort Monroe, it is an important asset of Hampton, the Commonwealth, and the nation. A unique site tells the history of America following the War of 1812 through World War II. Enslaved men took part in the building of Fort Wool. Robert E. Lee oversaw construction of the fortification. Andrew Jackson governed America for extended periods from the island. Fort Wool took part in the epic Civil War Battle of the “Monitor” and “Virginia.” Abraham Lincoln watched the attempt to capture Norfolk from the ramparts of Fort Wool; and Fort Wool was part of the Chesapeake Bay defenses during World War II. It continued to serve until the Army decommissioned it in the 1970s. -

Apache Misrule

Apache Misrule Item Type text; Article Authors Clum, John P. Publisher Arizona State Historian (Phoenix, AZ) Journal Arizona Historical Review Rights This content is in the public domain. Download date 30/09/2021 12:57:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623504 56 ARIZONA HISTORICAL REVIEW APACHE MISRULE A Bungling Indian Agent Sets the Military Arm in Motion By JOHN P. CLUM, Copyright, 1930 The official records heretofore quoted show that the SAN CARLOS APACHE police force had proved itself efficient and sufficient in the matter of the enforcement of order and disci- pline within their reservation from 1874 to 1880; that the great body of Apaches on that reservation were quiet and obedient during said period ; that the troops were removed from the reservation in October, 1875, and were not recalled at any time up to or during 1880. There was, however, one serious affair that occurred during the period above referred to, the exact cause of which I have not been able to ascertain. This was the breaking away from the reservation of more than half of the 453 Indians whom I brought over from Ojo Caliente, New Mexico, and located in the Gila Valley near the San Carlos sub-agency in May, 1877. In his annual report for 1878, Agent H. L. Hart mentions this outbreak briefly as follows : "On September 2, 1877, about 300 of the Warm Springs Indians left the reservation, taking with them a number of animals belonging to other Indians. They were followed by the police and Indian volunteers, and nearly all of the stock they had was captured, and 13 Indians killed, and 31 women and children brought back as prisoners by the dif- ferent parties that went in pursuit. -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

CIA Files Relating to Heinz Felfe, SS Officer and KGB Spy

CIA Files Relating to Heinz Felfe, SS officer and KGB Spy Norman J. W. Goda Ohio University Heinz Felfe was an officer in Hitler’s SS who after World War II became a KGB penetration agent, infiltrating West German intelligence for an entire decade. He was arrested by the West German authorities in 1961 and tried in 1963 whereupon the broad outlines of his case became public knowledge. Years after his 1969 release to East Germany (in exchange for three West German spies) Felfe also wrote memoirs and in the 1980s, CIA officers involved with the case granted interviews to author Mary Ellen Reese.1 In accordance with the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act the CIA has released significant formerly classified material on Felfe, including a massive “Name File” consisting of 1,900 pages; a CIA Damage Assessment of the Felfe case completed in 1963; and a 1969 study of Felfe as an example of a successful KGB penetration agent.2 These files represent the first release of official documents concerning the Felfe case, forty-five years after his arrest. The materials are of great historical significance and add detail to the Felfe case in the following ways: • They show in more detail than ever before how Soviet and Western intelligence alike used former Nazi SS officers during the Cold War years. 1 Heinz Felfe, Im Dienst des Gegners: 10 Jahre Moskaus Mann im BND (Hamburg: Rasch & Röhring, 1986); Mary Ellen Reese, General Reinhard Gehlen: The CIA Connection (Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Press, 1990), pp. 143-71. 2 Name File Felfe, Heinz, 4 vols., National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], Record Group [RG] 263 (Records of the Central Intelligence Agency), CIA Name Files, Second Release, Boxes 22-23; “Felfe, Heinz: Damage Assessment, NARA, RG 263, CIA Subject Files, Second Release, Box 1; “KGB Exploitation of Heinz Felfe: Successful KGB Penetration of a Western Intelligence Service,” March 1969, NARA, RG 263, CIA Subject Files, Second Release, Box 1. -

The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989

FORUM The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989 ✣ Commentaries by Michael Kraus, Anna M. Cienciala, Margaret K. Gnoinska, Douglas Selvage, Molly Pucci, Erik Kulavig, Constantine Pleshakov, and A. Ross Johnson Reply by Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana, eds. Imposing, Maintaining, and Tearing Open the Iron Curtain: The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014. 563 pp. $133.00 hardcover, $54.99 softcover, $54.99 e-book. EDITOR’S NOTE: In late 2013 the publisher Lexington Books, a division of Rowman & Littlefield, put out the book Imposing, Maintaining, and Tearing Open the Iron Curtain: The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989, edited by Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana. The book consists of twenty-four essays by leading scholars who survey the Cold War in East-Central Europe from beginning to end. East-Central Europe was where the Cold War began in the mid-1940s, and it was also where the Cold War ended in 1989–1990. Hence, even though research on the Cold War and its effects in other parts of the world—East Asia, South Asia, Latin America, Africa—has been extremely interesting and valuable, a better understanding of events in Europe is essential to understand why the Cold War began, why it lasted so long, and how it came to an end. A good deal of high-quality scholarship on the Cold War in East-Central Europe has existed for many years, and the literature on this topic has bur- geoned in the post-Cold War period. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

A Case Study of the Closing of Fort Devens

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1998 Lifestyle management education : a case study of the closing of Fort Devens. Janet B. Sullivan University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Sullivan, Janet B., "Lifestyle management education : a case study of the closing of Fort Devens." (1998). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 5347. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/5347 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT EDUCATION: A CASE STUDY OF THE CLOSING OF FORT DEVENS A Dissertation Presented by JANET B. SULLIVAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February 1998 School of Education ® Copyright 1998 by Janet B. Sullivan All Rights Reserved LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT EDUCATION: A CASE STUDY OF THE CLOSING OF FORT DEVENS A Dissertation Presented BY JANET B. SULLIVAN Approved as to style and content: C. Carey, Member ft SM-C+' ^/Sheila Mammen, Member Dean ACfQPMLEDGMENTS "Be All That You Can Be" is the Army's recruiting motto. I have been employed by the US Army since 1974. First, I was an Army officer; and now I am a federal civilian employee working as The Equal Employment Opportunity Officer at Fort Carson, Colorado.