Report 5 (Post-Games Evaluation) Sport Evidence Base

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London 2012 Olympic Games Declared Best Ever

Boxing NewsJuly - December 2012 | No. 10 LONDON 2012 OlYMPIC GAMES DECLARED BEST EVER YOUTH WORLDS ANNOUNCED STARS WSB SEASON III APB RECRUITMENT OF TOMORROW DELIGHTS CONTINUES Offi cial AIBA equipment provider since 1989 You can’t beat tradition Our history includes 3 Olympic games and more than 50 European championships, World cups and World championships. BOXING GLOVE AND HEAD GUARD The heart of the TOP TEN gloves has been revised in col- laboration with athletes from all over the world. The well- known Bayfi ll padding curved even more and the thumb area has been changed. The new shape allows a more com- fortable fi t and a simple set up for the fi st. TOP TEN The research and The technological Know How from existing TOP TEN prod- development com- ucts was used to develop a head guard made of leather, pany, a name with as the demand for a TOP TEN leather head guard has been reliability built in. overwhelming. BUDOLAND Sportartikel Vertriebs GmbH Am Grießenbach 8 · 83126 Flintsbach Tel. +43 (0) 80 34 / 90 990-0 · www.budoland.com TT Image.indd 1 03.11.11 09:34 AIBA President’S Message LOOKING TOWARDS A BRIGHTER FUTURE CONTENTS Dear members, athletes and fans, 1 President’s Message Welcome to this new issue of Boxing News magazine, the official publication of the International Boxing Association (AIBA). 2 APB / WSB R&Js and Supervisors Workshop About a year ago, I was sharing with you my excitement about the future holds for our sport. Following the resounding success of the London 2012 Olympic Games, AIBA’s duty is now to 6 AIBA Annual Awards capitalise on what we achieved so far in order to bring the sport of boxing to the next level. -

Black-History-Month Champions

As we conclude Black History Month, we take a look at a few of the iconic trailblazing black boxers who have made a huge impact on the Amateur boxing scene. There are many more boxers who are also deserving to be among this group. However, the ones chosen have had significant impact and have all gone on to inspire (or will inspire) the next generation of Black boxers in our great sport. Randy began boxing aged 12 for the Leamington Boys Club, In winning the Senior Title, Randy also became the youngest where he won 95 out of 100 amateur contests. He became Senior ABA champion at only 17 years old. He repeated the feat the only British amateur boxer to win the Junior and Senior the following year in 1946, then turned professional, where he National ABA titles in the same year, in 1945. continued to shine. One of the greatest amateur boxers ever produced in this country. Originally from Leicester, he however boxed his entire amateur Champion in every tournament he ever entered, and listed in the career for Standard Triumph ABC in Coventry. Won the Senior ABA Guinness Book of World Records as the only British boxer to win National Title in 1981 at Light-Middleweight and won a Bronze all 10 amateur titles, Errol also won a European under-19 Gold medal at the European Championships the same year. Captained medal in 1982. England team from 1980 to 1983. Won Olympic Gold at Super-Heavyweight at Sydney in 2000, Twice won the Senior National ABA Championship (1997 and 1998) thereby becoming Great Britain’s first Boxing Gold medallist since for Repton, and won Commonwealth Gold in 1998. -

Powerday Packs a Punch Behind GB Boxing in Olympic Qualification Tournament

Powerday packs a punch behind GB Boxing in Olympic Qualification Tournament EMBARGOED 1400, 9 March: Powerday – London’s largest family-owned waste management and recycling company – has agreed a partnership with GB Boxing, the organisation which manages the Olympic boxing programme. The agreement coincides with the Boxing Road to Tokyo Olympic qualifier (www.boxingroadtotokyolondon.org) which will begin at the Copper Box Arena this weekend (14-24 March 2020) when 13 members of the GB Boxing squad will have an opportunity to secure a place at the 2020 Olympic Games. The agreement was announced at an unveiling ceremony at the English Institute of Sport this afternoon, which featured the full Boxing Road to Tokyo squad. Powerday’s investment in boxing Powerday’s partnership with GB Boxing complements its longstanding presence in the sport and its unrivalled commitment to supporting aspiring boxers. Over the past five years, its charitable Powerday Foundation has sourced and delivered more than £14million of funding for London-based boxing clubs and projects at grass roots level. One of its biggest successes is a bursary scheme which has helped 40 youngsters over four years. These include Caroline Dubois, who is currently undefeated and has already won gold at the European Junior Championships, World Youth Championships and the Youth Olympic Games at Buenos Aires in 2018 – achievements which saw her recently crowned at the BBC Young Sports Personality of the Year for 2019. The 19-year-old is a member of the GB Boxing squad and will compete at the forthcoming Boxing Road to Tokyo qualifier where she hopes to secure her place at the 2020 Olympic Games. -

Is This Leading to the Alignment of Strategy and Gove

Governance change for National Governing Bodies of Sport (NSAs/NSOs/NSFs); Is this leading to the alignment of strategy and governance in England and the UK? TAYLOR, Marc Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/18250/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version TAYLOR, Marc (2017). Governance change for National Governing Bodies of Sport (NSAs/NSOs/NSFs); Is this leading to the alignment of strategy and governance in England and the UK? In: Play The Game 2017 - Riding waves of change, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 26-30 November 2017. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Governance change for National Governing Bodies of Sport (NSAs/NSOs/NSFs); Is this leading to the alignment of strategy and governance in England and the UK? Original image Source: © Marc Taylor, 2015‐ Marc Taylor @MTSportBusiness +44 (0) 781 854 3423 2496 [email protected] or [email protected] www.shu.ac.uk/sport/academy © Marc Taylor, 2017‐ 1 www.cardiff.ac.uk/law‐politics/For educational, academic and research purposes, not for commercial purposes Presentation outline Marc Taylor • Backgrounds and relevance to the conference agenda / Framing of research thinking • Research objectives, approach and case boundaries • Data collection, analysis and findings • Observations: research gaps (others/collaboration) -

Sport England Annual Report 2004-2005

Presented pursuant to section 33(1) and section 33(2) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 (as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998) Sport England Annual Report and Accounts 2004-2005 ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 19 January 2006 LAID BEFORE THE PARLIAMENT BY THE MINISTERS 19 January 2006 LONDON: The Stationery Office 19 January 2006 HC 302 £ Contents 2004-05 Annual report against DCMS-Sport Page 3 England funding agreement 2003-06 Sport England - Summary of Lottery Awards 2004-05 Page 12 Sport England Lottery Awards 2004-05 - Awards over £100,000 Page 14 Ongoing awards over £5 million and their status Page 19 Sport England - Lottery Accounts Page 20 Performance Indicators 2004-05 Sport England Lottery Fund Monitoring & Evaluation Page 21 Financial directions issued under sections 26 (3), (3A) and (4) Page 24 of The National Lottery Etc. Act 1993 (as amended by The National Lottery Act 1998) Policy Directions Issued under Section 26 of the National Page 28 Lottery etc Act 1993 amended 1998 The English Sports Council National Lottery Distribution Page 31 Account for the year ended 31 March 2005 The Space for Sport and Arts Programme Memorandum Page 64 Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2005 The English Sports Council and English Sports Council Group Page 69 Consolidated Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2005 2 2004-05 ANNUAL REPORT AGAINST DCMS-SPORT ENGLAND FUNDING AGREEMENT 2003-06 2004-05: Another year of progress and achievement Work area 04/05: Key achievements Strategic Leadership Sport England celebrates -

MEET the SPEAKERS IAN GATT Subject: Acute Sport Injuries of the Upper Limb; Can Acupuncture Make a Difference?

MEET THE SPEAKERS IAN GATT Subject: Acute sport injuries of the Upper Limb; Can acupuncture make a difference? Time: 15:05 - 16:05 Ian Gatt has been a sport physiotherapist for 20 years, with a considerable period invested in managing the medical services for GB Boxing. He has attended all major competitions with boxing supporting elite athletes on their path to success through the London 2012, Rio 2016, and current Tokyo 2020 Olympic Cycles. Ian has been a Visiting Lecturer at UCL since 2013, and is undergoing a PhD in Wrist Biomechanics at Sheffield Hallam University. He is an Upper Limb Injury Specialist with the prestigious English Institute of Sport (EIS) providing his expertise to Olympic and Paralympic Sports. Ian regularly delivers national/international educational workshops and presentations on diverse areas linked to sport injuries. Further, he provides private injury consultations in Sheffield, London, and Malta. Follow him on Twitter (@iangattphysio), Instagram (iangattgattman) and Linkedin (Ian Gatt). MARIE LORE BUIDIN Subject: Acupuncture in the treatment of Pulmonary Disease Time: 08:45 - 09:45am Marie-Lore Buidin physiotherapist and L.Ac studied acupuncture in Belgium at the Jing Ming acupuncture college (1999-2002) with internship in China (Nanjing). She also trained with Master Li Ruheng (Nanjing) in Tai Chi Chuan Yang Style and Tai Ji Jian. Her focus as a physiotherapist for more than 30 years was treating adults and children with COPD, asthma and cystic fibrosis. She worked in close collaboration with specialized pediatric pneumologists. In acupuncture she has specialized herself in treating cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease and psycho-emotional issues, in which she has more than 16 years of advanced knowledge and specific clinical experience. -

Annual Report 2018 2 NEWCASTLE EAGLES COMMUNITY FOUNDATION

Annual Report 2018 2 NEWCASTLE EAGLES COMMUNITY FOUNDATION FACTS AND FIGURES 2017-18 schools participated 86 up 18 on last year 7,132 young people extra-curricular school9 clubs 6 1 took part established within the council champion of East End of Newcastle finals champions final 419 young people junior players have attended 0 3 some of which have represented 25-30 the North East at the junior 15 championships times schools with new adult or more more than... 10 players national 400 children participating 1 league team players club teams compete 60 within our junior club or after league 49 school sites 62 school club 20sites in 12 Gateshead officiating staff for CVL more than foundation all the BBL squad players 7 trustees deliver Hoops4Health full time roadshows 7000 9 staff volunteer hours part time donated this season 40 staff zero our clubs cater from 5 years old to senior age groups core-funding ANNUAL REPORT 2018 3 INTRODUCTION The 2017-2018 year has been one of the biggest steps forward for the Newcastle Eagles and Eagles Community Foundation with the development of the new Eagles Community Arena one step closer to opening and providing a stable base for basketball here in the North East. We are extremely proud of the step that we have made for basketball and will continue to push the sport forward. This report will give an insight into the depth of interventions we deliver daily, amounting to over 200 sessions per week, almost all year round. The report is dedicated to everyone who works as a part of the Eagles team to provide a foundation for young people and adults to participate in sport and build a healthy, active lifestyle as well as provide countless volunteering opportunities for the community. -

Environment Template (REF5) Institution: Sheffield Hallam University

Environment template (REF5) Institution: Sheffield Hallam University Unit of Assessment: 26 Sport and Exercise Sciences, Leisure and Tourism a. Overview UoA 26 at Sheffield Hallam University (SHU) consists of 32 FTEs comprising 34 staff. Category A staff included in this submission are located in four research centres: • Centre for Sport & Exercise Sciences (CSES) - 10.4 FTE staff submitted; • Centre for Sports Engineering Research (CSER) - 8.4 FTE staff submitted; • Sport Industry Research Centre (SIRC) - 8 FTE staff submitted; • Tourism, Hospitality & Events Special Interest Group (THESIG) - 5.2 FTE staff submitted. Staff from CSES and SIRC were submitted in RAE 2008. CSER was created in 2009/10 when the sports engineering group within CSES expanded to become a centre in its own right. THESIG encompasses two separate centres included in RAE 2008 (Centre for International Tourism Research, and Centre for International Hospitality Management Research). Researchers from the first three centres are in the Faculty of Health and Wellbeing, based at the Collegiate Campus, whilst researchers from tourism are in the Sheffield Business School, based at the City Campus. b. Research strategy UoA research strategy in RAE 2008 The five year strategy in RAE 2008 aimed at consolidating research strengths and building on their successes. Progress against the three objectives laid out in RAE 2008 is as follows: 1. To grow capacity, develop expertise and academic excellence in each of the research areas and exploit synergies between the themes. The number of submitted staff is one more than for RAE 2008, and each research centre demonstrates areas of continually developing expertise and academic excellence. -

The Rio Review the Official Report Into Ireland's Campaign for the Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games

SPÓRT ÉIREANN SPORT IRELAND The Rio Review The official report into Ireland's campaign for the Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games RIO 2016 REVIEW Foreword The Olympic and Paralympic review process is an essential component of the Irish high performance system. The implementation of the recommendations of the quadrennial reviews has been a driver of Irish high performance programmes for individual sports and the system as a whole. The Rio Review process has been comprehensive and robust. The critical feature of this Review is that the National Governing Bodies (NGBs) took a greater level of control in debriefing their own experiences. This Review reflects the views of all the key players within the high performance system. Endorsed by Sport Ireland, it is a mandate for the NGBs to fully implement the recommendations that will improve the high performance system in Ireland. There were outstanding performances in Rio at both the Olympic and Paralympic Games. The Olympic roll of honour received a new addition in Rowing, with Sailing repeating its podium success achieved in Moscow 1980, demonstrating Ireland's ability to be competitive in multiple disciplines. Team Ireland has built on the success of Beijing and London, and notwithstanding problems that arose, Rio was a clear demonstration that Ireland can compete at the very highest levels of international sport. Sport Ireland is committed to the ongoing development of the Sport Ireland Institute and adding to the extensive facilities on the Sport Ireland National Sports Campus. These are real commitments to high performance sport in Ireland that will make a significant difference to Irish athletes who aspire to compete at the top level. -

Governance Change for National Governing Bodies of Sport Is This

Governance change for National Governing Bodies of Sport (NSAs/NSOs/NSFs); Is this leading to the alignment of strategy and governance in England and the UK? Original image Source: © Marc Taylor, 2015- Marc Taylor @MTSportBusiness +44 (0) 781 854 3423 2496 [email protected] or [email protected] www.shu.ac.uk/sport/academy © Marc Taylor, 2017- 1 You created this PDF from anwww.cardiff.ac.uk/law application that isFor not educational, licensed-politics/ to print academic to novaPDF and research printer (purposes,http://www.novapdf.com not for commercial) purposes Presentation outline Marc Taylor • Backgrounds and relevance to the conference agenda / Framing of research thinking • Research objectives, approach and case boundaries • Data collection, analysis and findings • Observations: research gaps (others/collaboration) © Marc Taylor, 2017- 2 You created this PDF from an application that isFor not educational, licensed to print academic to novaPDF and research printer (purposes,http://www.novapdf.com not for commercial) purposes Background and relevance to the conference agenda Framing of research thinking “Governance in Sport: Change or be changed” © Marc Taylor, 2017- 3 You created this PDF from an application that isFor not educational, licensed to print academic to novaPDF and research printer (purposes,http://www.novapdf.com not for commercial) purposes Introduction Background • Full time in academia since 2011 • Academy of Sport and Physical Activity (Sheffield Hallam University) and • Part time PhD student (Cardiff University) -

To Read the Badge Online for April 2014 Issue

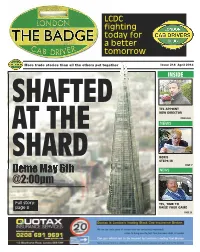

LCDC fighting today for a better tomorrow More trade stories than all the others put together Issue 218 April 2014 INSIDE SHAFTED TFL APPOINT NEW DIRECTOR PAGES 4&5 AT THE NEWS BORIS SHARD STEPS IN PAGE 7 Demo May 6th NEWS @2:00pm Full story: TFL, TIME TO page 3 RAISE YOUR GAME PAGE 16 2 Issue 218 - April 2014 Editorial Grant Davis trade stood up for itself and stopped this undermining of our trade. As you can see from the front page Is this the future we can expect from the Club has backed calls for a TFL under the new SIPs regime? Published by drive-in demonstration at The Shard Minicabs outside the door, and the The London Cab Drivers’ Club Ltd. licensed taxitrade down the Unit A 303.2, building in St Thomas Street on the Tower Bridge Business Complex Tuesday 6th May. roadSSS..literally. Tower Point, 100 Clements Road The Shard has already become in the BE THERE ON THE 6TH MAY Southwark, London SE16 4DG short time of opening a major London iconic buildings attracting thousands of ----------------------------------- Telephone: 020 7232 0676 visitors every week. It is vital that the Surface Intergration seen from last month’s edition of the E-mail for membership enquiries: licensed taxi trade be given an Programme Badge, the Mayor agreed with me that E-mail: [email protected] opportunity to be able to offer its world Talking of SIPs, TFL have finally after it was indeed a meter but TFL still Web: lcdcorg.wordpress.com class service to what has already six months found someone to be the seem reluctant to take the same become one of the most famous Editor: Grant Davis new Director of Service Operations. -

Twitter @Northunisport Facebook.Com

twitter @NorthUniSport facebook.com/northumbriauniversitysport instagram @NorthumbriaUniSport STUDENT SPORT GUIDE 2016-17 RANKED 8TH IN BUCS NATIONAL LEAGUE TABLELE BUCS National League Table 2015-16 WHICH? UNIVERSITY TOP 10 FOR SPORT Contents Welcome 1 North Programme 2-7 500+ STUDENTS Team Northumbria 8 CONTRIBUTING Sport Scholarships 9 OVER 800 HOURS Volunteering 12-13 OF VOLUNTEERING & Internships Foundation 14 Supporters Club 15 4TH IN THE UK Sport Contacts 16 FOR SPORTS Locations 17 STUDENT EXPERIENCE Times Higher Education Student Experience Survey 2016 WELCOME On behalf of my entire team I would like to welcome both new and returning students to Northumbria Sport, your University sport service. Last year was the most successful in our history membership options offer excellent value for and whilst I am enormously proud of our money. Check out full details on page 2. achievements, including being ranked in the In addition to NORTH, I am also delighted to see UK’s Top 5 for Sport in the independent Times further changes to our TEAM NORTHUMBRIA Higher Education Student Satisfaction Survey programme including the opening of our new 2016, we are determined to deliver an even High Performance Centre, formerly Coach more exciting programme in 2016/17. Lane Sports Centre. This new Centre will offer Not only will it be a new, dynamic and a dedicated environment for team training for student centred programme, because we are a number of sports and will include a new S&C Northumbria, it will be of world class quality. Suite and Student Athlete Centre. I’m confident Everything we do is underpinned by our values that together with other changes we can once of Engage, Inspire, Achieve – these core values again go on and achieve a record number of Colin drive excellence in all of the team and right BUCS points and retain the Stan Calvert Cup for Colin Stromsoy, across our service.