SC00-1527 Sawczak Vs. Goldenberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

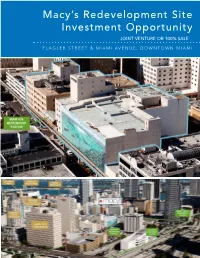

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Second Motion to Extend the Termination Date of the Liquidating Trusts

Case 09-36379-EPK Doc 3480 Filed 05/22/18 Page 1 of 24 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA WEST PALM BEACH DIVISION www.flsb.uscourts.gov IN RE: PALM BEACH FINANCE PARTNERS, L.P., CASE NO. 09-36379-EPK PALM BEACH FINANCE II, L.P., CASE NO. 09-36396-EPK (Jointly Administered) Debtors. / LIQUIDATING TRUSTEE’S SECOND MOTION TO EXTEND THE TERMINATION DATE OF THE LIQUIDATING TRUSTS Barry E. Mukamal, in his capacity as liquidating trustee (“Trustee”) for the Palm Beach Finance Partners Liquidating Trust and Palm Beach Finance II Liquidating Trust (together, the “Trusts”), respectfully requests an Order of the Court extending the termination date of the Liquidating Trusts by two years from December 31, 2018 until December 31, 2020. In support, the Trustee states as follows: 1. On October 21, 2010, the Court entered the Order Confirming Second Amended Joint Plan of Liquidation of Barry Mukamal, as Chapter 11 Trustee of Palm Beach Finance Partners, L.P. and Palm Beach Finance Partners II, L.P. and Geoffrey Varga, as Joint Official Liquidator of Palm Beach Offshore, Ltd., and Palm Beach Offshore II, Ltd. [EFC No. 444] (“Confirmation Order”).1 2. The Plan’s Effective Date was November 1, 2010. [ECF No. 465]. 3. The Confirmation Order provides in paragraph 6 that “[o]n the Effective Date, the Trustee, on behalf of the Debtors and the Beneficiaries, is authorized to execute the Liquidating Trust Agreements and take all steps necessary to establish the Liquidating Trusts.” The Trustee established the Trusts following entry of the Confirmation Order. -

Filing # 131885989 E-Filed 08/02/2021 07:13:56 PM

Filing # 131885989 E-Filed 08/02/2021 07:13:56 PM IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE 11TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT IN AND FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA CIRCUIT CIVIL DIVISION CASE NO.: KEY BISCAYNE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION, INC., a Florida not for profit corporation, Plaintiff, v. TONY CAMPAIGNE, individually, Defendant. / COMPLAINT Plaintiff, KEY BISCAYNE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION, INC., sues Defendant TONY CAMPAIGNE and alleges as follows: JURISDICTION, PARTIES AND VENUE 1. This is an action for damages in excess of Thirty Thousand and No/100 ($30,000), exclusive of interest, costs and attorneys’ fees. 2. Plaintiff, KEY BISCAYNE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION, INC. (“the Foundation”) is a Florida Not for Profit Corporation with its principal place of operations in Miami-Dade County. 3. Defendant, TONY CAMPAIGNE is an individual residing in Miami-Dade County, and is sui juris. 4. All conditions precedent to the institution of this action either have occurred, or have been waived. Museum Tower . 150 West Flagler Street, Suite 2200 . Miami, FL 33130 . (305) 789-3200 5. Venue is proper in Miami-Dade County, as the conduct alleged and the damages resulting therefrom, occurred in Miami-Dade County. FACTS A. The Foundation 6. The Foundation exists for a number of reasons, the principal one of which is to support charitable causes and provide technical, advisory, and depository support for others who are similarly motivated to contribute to the greater good of a just and caring society. A reputation for integrity and compliance with the law is essential for a charitable foundation to serve its community. 7. Through extraordinary good work, carried out by honest, competent and caring people, the Foundation has earned the right to enjoy a reputation as a charitable, competent, honest, and law-abiding institution. -

Miami DDA Area Offices

NE 28th St NE 27th Te NW 28th St NE 27th St NW 27th St NE 26th Te No. Class Name Address Year RBA 1 A 10 Museum Park 1040 Biscayne Blvd 2007 24,000 \ NW 26th St NE 26th St 2 A 900 Biscayne Bay 900 Biscayne Blvd 2008 95,000 3 A Marina Blue 888 Biscayne Blvd 2008 750,000 4 B NAP of the Americas 50 NE 9th ST 2001 750,000 NW 25th St NE 25th St 5 A 2 MiamiCentral 601 NW 1st Ave 2018 190,000 NE 24th St 6 A 3 MiamiCentral 161 NW 6th ST 2018 95,000 NW 24th St NW 24th St NE 24th St 7 B The Citadel 49 NW 5th ST 1950 50,000 8 B Courthouse Center 40 NW 3rd ST 2009 40,300 NW 23rd St NW 23rd St 9 B 36 NE 2nd ST 36 NE 2nd ST 1925 205,172 10 B Chase Bank Building 150 SE 2nd Ave 1966 125,388 NE 23rd St NE 22nd Te 11 B Bayside Office Center 141 NE 3rd Ave 1923 57,093 12 B 261 Office Lofts 261 NE 1st ST 1982 34,741 NE 22nd St 13 B New World Tower 100 N Biscayne Blvd 1966 285,000 NW 22nd St Ave 2nd NE 14 C Capital Building 117 NE 1st Ave 1926 85,000 15 C Congress Building 111 NE 2nd Ave 1922 242,294 NE 21st St Dade Commonwealth 16 B Building 139 NE 1st ST 1927 43,265 17 B One Bayfront Plaza 100 S Biscayne Blvd 1959 312,896 BISCAYNE BOULEVARD BISCAYNE Flagler Federal NE 20th St 18 B Building 101-111 NE 1st ST 1961 64,470 N MIAMI AVE MIAMI N NW Miami Ct Miami NW NW 1st Ave 1st NW NW 2nd Ave 2nd NW NE 19th Te NW 1st Ct 1st NW NW 20th St Pl 1st NW 19 B Historic Post Office 100 NE 1st Ave 1912 37,600 20 B Metromall Building 1 Ne 1st ST 1926 156,000 NE 19th St 21 C 219-223 E Flagler ST 219-223 E Flagler ST 1984 42,000 22 B A.I. -

Biscayne Miami, Florida, Usa

900 BISCAYNE MIAMI, FLORIDA, USA 600-700 Biscayne BISCAYNE BOULEVARD (54,787 ADT) FOR LEASE > GROUND FLOOR RETAIL & RESTAURANT 1,626 SF Ground Floor Retail & Restaurant Pablo Camposano Dave Preston off Biscayne Boulevard, offering high Senior Associate Executive Managing Director +1 786 210 2730 +1 786 517 4972 visibility and easy access to many [email protected] [email protected] Downtown attractions. BISCAYNE BLVD (54,787 ADT) SITE PLAN NE 9TH STREET NE 10TH STREET 1,626 SF NE 2ND AVENUE BISCAYNE 900 MIAMI, FLORIDA, USA The property is located in the heart of Downtown Miami, directly across from the American Airlines Area, Bayside Market Place and Bayfront Park. Offering up to 1,626 square feet of retail space with convenient access to the Brightline, Venetian Causeway, Macarthur Causeway, Port of Miami and Watson Island. 1,626 SF Retail Located at 900 Convenient & Restaurant Biscayne Blvd, Highway Access Available Miami, FL 54,787 Daily Excellent Public Traffic Count on Walkability Transit Access Biscayne Blvd Carlos Zapata Square Tower Station Knight Concert DOWNTOWN MIAMI Hall DEVELOPMENTS Proposed Ramp to I-95 1000 Museum Tower Future Miami 900 Biscayne Blvd Worldcenter Soleste 600-700 Biscayne Grand Central Multi-Use 3 MiamiCentral Development Project Marriott 5.6 Million Convention Annual Passengers Center Hotel 400 Biscayne Multi-Use Development Block 55 Waldorf Vertical Okan Downtown Astoria Tower Big Box Tower 5th Krystal Tower Post Office (proposed) X Miami/ Grand Redevelopment/ The Guild Station Entertainment -

FOR LEASE > 169 E Flagler Street

2,360 – 3,460 SF FLAGSHIP CORNER FOR LEASE > 169 E Flagler Street | Miami, Florida Jonathan Carter Dave Preston Executive Managing Director Executive Managing Director RETAIL & RESTAURANT SPACE +1 786 517 4971 +1 786 517 4972 for lease in the heart of the business district [email protected] [email protected] FOR LEASE 169 E Flagler Street | Miami, Florida colliers.com Site Plan Available #151 OVER 1,700 sf UNDER #153 1,700 sf #157 2,600 sf #100 3,200 sf #159 1,287 sf FNB! BREWERY COMING SOON #180 1,466 sf #169 1,100 sf #50 5,994 sf #70 #80 #98 2,700 sf 1,116 sf 2,500 sf FNB! BREW PUB #199 COMING SOON 2,360 sf 5050 FNB!FNB! Brew Brew Pub Pub 5,994 5,994 sf sf 100100 FNB!FNB! Brewery Brewery 3,2003,200 sf sf 159159 VinaigretteVinaigrette 1,2871,287 sf sf 70 Available 2,700 sf 151 Over Under 1,700 sf 169 Giardino’s 1,100 sf 70 Available 2,700 sf 151 Over Under 1,700 sf 169 Available 1,100 sf 80 Manna Life Food 1,116 sf 153 UPS 1,700 sf 180 Available 1,466 sf 9880 AvailableManna Life Food 1,116 2,500 sf sf 157153 LostUPS Boy Dry Goods 1,7002,600 sf sf 199180 AvailableAvailable 1,4662,360 sf sf 98 Carrot Express 2,500 sf 157 Lost Boy Dry Goods 2,600 sf 199 Available 2,360 sf Carlos Zapata Square Tower Station I-395 Reconstruction/ Enhancements Knight Concert Hall Proposed Ramp to I-95 1000 Museum Tower Future Miami Worldcenter Soleste 600-700 Biscayne Grand Central Multi-Use 3 MiamiCentral Development Project Marriott 5.6 Million Convention Annual Passengers Center Hotel 400 Biscayne Multi-Use Development Block 55 Waldorf -

Filing # 128236087 E-Filed 06/07/2021 02:50:09 PM

Filing # 128236087 E-Filed 06/07/2021 02:50:09 PM IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA THE FLORIDA BAR, Supreme Court Case No. SC20-160 Complainant, The Florida Bar File No./Lower v. Tribunal No.2020-70,055(11C-MFC) MARK S. SCOTT, Respondent. ______________________________________/ RESPONDENT'S FIFTH STATUS REPORT AS TO FEDERAL PROCEEDINGS Pursuant to this Court's March 12, 2020 Order Granting Respondent's Unopposed Motion for Temporary Stay (requiring that "Respondent’s Counsel is to advise this Court ninety days from the date of this order, and every ninety days thereafter, of the status of the federal proceedings"), Respondent's undersigned counsel hereby provides this Fifth Status Report to the Court,1 that in regard to the Federal proceeding of United States of America v. Mark S. Scott, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (Case No. 1:17- cr-00630 (ER)), Respondent's Motion for Judgment of Acquittal or, RECEIVED, 06/07/2021 02:50:27 PM, Clerk, Supreme Court 1 The First Status Report was timely filed with the Court on June 9, 2020, the Second Status Report was timely filed with the Court on September 8, 2020, the Third Status Report was timely filed with the Court on December 7, 2020, and the Fourth Status Report was timely filed with the Court on March 8, 2021. RUSSOMANNO & BORRELLO, P.A. Supreme Court Case No. SC20-160 in the Alternative, a New Trial, has been briefed by the parties and remains pending without a ruling by the Federal Court Judge as of the date this Fifth Status Report is being filed with this Court. -

Filing # 111073418 E-Filed 07/30/2020 08:05:38 PM

Filing # 111073418 E-Filed 07/30/2020 08:05:38 PM IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE 11TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA COMPLEX BUSINESS LITIGATION DIV. CASE NO.: 2019-16913-CA-01 (44) OPA-LOCKA COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, INC., a Florida non-profit corporation, Plaintiff, v. HK ASWAN, LLC, a Massachusetts limited liability company, HALLKEEN MANAGEMENT, INC., a Massachusetts corporation, and ASWAN VILLAGE ASSOCIATES, LLC, a Florida limited liability company, Defendants. / DEFENDANTS HK ASWAN, LLC, HALLKEEN MANAGEMENT, INC., AND ASWAN VILLAGE ASSOCIATES, LLC’S MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION OF OMNIBUS ORDER, DATED JULY 7, 2020 Defendants HK Aswan, LLC (“HK Aswan”), HallKeen Management, Inc. (“HallKeen”), and Aswan Village Associates, LLC (“Owner”) move this Court to reconsider and set aside the Court’s non-final Omnibus Order on: (i) Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment; (ii) Plaintiff’s Renewed Motion for Partial Summary Judgment; (iii) Plaintiff’s Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings or, in the Alternative, Partial Summary Judgment; and (iv) Defendant HallKeen’s Motion for Summary Judgment on Count I (“Omnibus Order”). The Court should reconsider the Omnibus Order, enter summary judgment in Defendants’ favor and against Plaintiff Opa-locka Community Development Corporation, Inc. (“OLCDC”),1 and enter summary judgment in HallKeen’s favor as to Count I.2 1 The Court found that OLCDC is entitled to specific performance but did not identify on which cause of action where OLCDC requested specific performance, either Count II or Count III, it was granting summary judgment. 2 Defendants refer to deposition exhibits in the record as “Dep. -

Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 1 of 13

Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 1 of 13 Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 2 of 13 Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 3 of 13 Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 4 of 13 Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 5 of 13 Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 6 of 13 Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 7 of 13 Case 91-14561-PGH Doc 5607 Filed 03/04/09 Page 8 of 13 Timothy J. Norris, Esq. Jacob J. Frohman, Esq. Mark D. Bloom, Esq.** Duane Morris LLP Kelley, Drye & Warren LLP Greenberg Traurig, P.A. 200 South Biscayne Blvd. 101 Park Avenue 1221 Brickell Avenue Suite 3400 New York, NY 10178 Miami, Florida 33131 Miami, Florida 33131 State of Florida Patricia A. Redmond, Esq.** Michael P. Brundage, Esq. Department of Revenue Stearns, Weaver, Miller Hill, Ward & Henderson, P.A. Bankruptcy Section 2200 Museum Tower Post Office Box 2231 P.O. Box 6668 150 West Flagler Street Tampa, FL 33610 Tallahassee, FL 3231 4-6668 Miami, FL 33130 Isaac M. Pachulski, Esq. Barry D. Hunter, Esq. Stutman, Treister & Glatt James Donnell, Esq. Brown, Todd & Heyburn, PLLC 1901 Avenue of the Stars Andrews & Kurth th 2700 Lexington Financial Center 12 Floor 4200 Texas Commerce Tower 250 West Main Street Los Angeles, CA 90067 Houston, TX 77002 Lexington, Kentucky 40507 Richard P. Carmody J. -

Capital Projects by County-Community Projects Only

CAPITAL PROJECTS BY COUNTY-COMMUNITY PROJECTS ONLY County and Funding Agency Fund Line Item Item/Project Name Appropriations Adams Department of Natural Resources 7035 C725E2 Adams County Splash Pad $250,000 Ohio Facilities Construction Commission 7030 C230C8 Serpent Mound $50,000 Department of Mental Health and 7033 C58001 Adams County Wilson Children's $250,000 Addiction Services Home Total Adams $550,000 Allen Department of Transportation 7026 C77706 Allen County Building Demolition $200,000 Department of Rehabilitation and 7027 C50100 Allen County Jail Facility $100,000 Correction Department of Mental Health and 7033 C58001 Cornerstone of Hope - Allen County $200,000 Addiction Services Total Allen $500,000 Ashland Department of Natural Resources 7035 C725E2 2019 Loudonville Swimming Pool $75,000 Improvements Project Department of Natural Resources 7035 C725E2 Ashland Brookside Tennis Courts $300,000 Department of Natural Resources 7035 C725E2 Shiloh Firestone Park Restoration $12,000 Ohio Facilities Construction Commission 7030 C230FM Schine's Theater $500,000 Ohio Facilities Construction Commission 7030 C230FM Freer Children's County Home $170,000 Total Ashland $1,057,000 Ashtabula Department of Agriculture 7026 C70022 Ashtabula County Agricultural $250,000 Facility Improvements Department of Natural Resources 7035 C725E2 Grand River Conservation Campus $385,000 Department of Natural Resources 7035 C725E2 Indian Mound Park & Cultural $60,000 Education Project Department of Youth Services 7028 C47027 Ashtabula Juvenile Court Resources -

Case 1:11-Cv-22026-MGC Document 68 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/19/2011 Page 1 of 4

Case 1:11-cv-22026-MGC Document 68 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/19/2011 Page 1 of 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA MIAMI DIVISION Case No. 11-22026-Civ-COOKE/TURNOFF DR. BERND WOLLSCHLAEGER, et al., Plaintiffs, vs. FRANK FARMER, in his official capacity as Surgeon General of the State of Florida, et al., Defendants. _____________________________________/ NOTICE OF APPEARANCE COMES NOW, Gerald E. Greenberg, of the law firm of Stearns Weaver Miller Weissler Alhadeff & Sitterson, P.A., and respectfully gives notice of appearance as attorney for the proposed amici curiae, the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida, Inc., Broward County Medical Association, Broward County Pediatric Society, Palm Beach County Medical Society, Children’s Healthcare Is a Legal Duty, Inc., the Early Childhood Initiative Foundation, and the University of Miami School of Law Children and Youth Clinic, in the above styled case. Case 1:11-cv-22026-MGC Document 68 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/19/2011 Page 2 of 4 Case No. 11-22026-Civ-COOKE/TURNOFF Dated: July 19, 2011 Respectfully submitted, STEARNS WEAVER MILLER WEISSLER ALHADEFF & SITTERSON, P.A. Museum Tower, Suite 2200 150 West Flagler Street Miami, Florida 33130 Telephone: (305) 789-3200 Facsimile: (305) 789-3395 s/ Gerald E. Greenberg GERALD E. GREENBERG Florida Bar No. 440094 [email protected] GORDON M. MEAD, JR. Florida Bar No. 049896 [email protected] Attorneys for Proposed Amici Curiae CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that on July 19, 2011, I electronically filed the foregoing document with the Clerk of the Court using CM/ECF. -

Fontainebleau Las Vegas Contract Litigation

Case 1:09-md-02106-ASG Document 192 Entered on FLSD Docket 12/06/2010 Page 1 of 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA CASE NO 09-MD-02106-CIV-GOLD/GOODMAN IN RE: FONTAINEBLEAU LAS VEGAS CONTRACT LITIGATION MDL No. 2106 This document relates to all actions. / TERM LENDERS’ MOTION FOR DETERMINATION OF FONTAINEBLEAU RESORT’S WAIVER OF PRIVILEGE; MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT THEREOF Pursuant to the Court’s Order on Motion for Sanctions, Plaintiffs in Avenue CLO Fund, Ltd., et al. v. Bank of America, et al., Case No. 09-CV-23835-ASG (S.D. Fla.) and ACP Master, Ltd., et al. v. Bank of America, N.A., et al., Case No. 10-CV-20236-ASG (S.D. Fla.) (the “Term Lenders”), by and through their undersigned counsel, move this Court for an order determining that Fontainebleau Resorts, LLC (“FBR”) waived all applicable privileges when it knowingly produced hundreds of thousands of documents to the Term Lenders without conducting any review or taking any other steps to prevent the disclosure of privileged documents. I. INTRODUCTION After repeated orders, FBR finally produced electronic documents in response to the Term Lenders’ subpoena. FBR made no effort to limit its production to responsive documents. Instead, it produced its entire document server, more than 600,000 documents, including hundreds of thousands of documents having nothing to do with any of the topics set forth in the Term Lenders’ subpoena. Nor did FBR take any steps (much less the “reasonable steps” required by Rule 502(b)) to ensure that its document dump did not include privileged documents.