Mapping Political Regime Typologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Hybrid Regimes, the Rule of Law, and External Influence on Domestic Change

9780415451024-Ch01 4/16/08 7:00 PM Page 1 1 Hybrid regimes, the rule of law, and external influence on domestic change Amichai Magen and Leonardo Morlino Introduction At the beginning of the twenty-first century, two sets of phenomena are challenging our understanding of democracy and democratization. First, transition from authoritarian regimes into some form of democracy is no longer understood to constitute the most prevalent or important change in worldwide democratization processes. Second, contemporary processes of domestic political change are unfolding within a radically transformed inter- national environment compared to even two decades ago (Gershman 2005; Whitehead 2004). As the Freedom House organization has been underlining in its reports over the last decade,1 etc. the stable, closed authoritarian regime has become something of a rarity. While in 1974 – the year that heralded the launch of the “third wave” of global democratization with the Portuguese Revolução dos Cravos (Huntington 1991) – the number of democracies on the planet stood at a mere 39, at the end of 2006, out of 193 independent countries, 123 ranked as electoral democracies (Freedom House 2006). Thus, for the first time in human history, democracy had become not only a universal aspiration, but the predominant form of government in the world, and the only form enjoying broad international legitimacy (McFaul 2004; Gershman 2005; Sen 1999). The triumph of democracy, moreover, has (so far at least) proven steadier than many would have expected, with cases of outright breakdowns and reversions to autocracy, and fears of a “reverse wave” to autocracy, largely held at bay (Diamond 2000; 2005). -

THE RISE of COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A

Elections Without Democracy THE RISE OF COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way Steven Levitsky is assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University. His Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Lucan A. Way is assistant professor of political science at Temple University and an academy scholar at the Academy for International and Area Studies at Harvard University. He is currently writing a book on the obstacles to authoritarian consolidation in the former Soviet Union. The post–Cold War world has been marked by the proliferation of hy- brid political regimes. In different ways, and to varying degrees, polities across much of Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbab- we), postcommunist Eurasia (Albania, Croatia, Russia, Serbia, Ukraine), Asia (Malaysia, Taiwan), and Latin America (Haiti, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru) combined democratic rules with authoritarian governance during the 1990s. Scholars often treated these regimes as incomplete or transi- tional forms of democracy. Yet in many cases these expectations (or hopes) proved overly optimistic. Particularly in Africa and the former Soviet Union, many regimes have either remained hybrid or moved in an authoritarian direction. It may therefore be time to stop thinking of these cases in terms of transitions to democracy and to begin thinking about the specific types of regimes they actually are. In recent years, many scholars have pointed to the importance of hybrid regimes. Indeed, recent academic writings have produced a vari- ety of labels for mixed cases, including not only “hybrid regime” but also “semidemocracy,” “virtual democracy,” “electoral democracy,” “pseudodemocracy,” “illiberal democracy,” “semi-authoritarianism,” “soft authoritarianism,” “electoral authoritarianism,” and Freedom House’s “Partly Free.”1 Yet much of this literature suffers from two important weaknesses. -

Managing Opposition in a Hybrid Regime

Edinburgh Research Explorer Managing Opposition in a Hybrid Regime Citation for published version: March, L 2009, 'Managing Opposition in a Hybrid Regime: Just Russia and Parastatal Opposition', Slavic Review, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 504-527. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/25621653> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Slavic Review Publisher Rights Statement: © March, L. (2009). Managing Opposition in a Hybrid Regime: Just Russia and Parastatal Opposition. Slavic Review, 68(3), 504-527. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Managing Opposition in a Hybrid Regime: Just Russia and Parastatal Opposition Author(s): Luke March Source: Slavic Review, Vol. 68, No. 3 (Fall, 2009), pp. 504-527 Published by: Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25621653 . Accessed: 03/02/2014 06:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . -

HYBRID REGIMES in MODERN TIMES: Between Democracy and Autocracy

HYBRID REGIMES IN MODERN TIMES: Between Democracy and Autocracy Dr. Inna Melnykovska Assistant Professor Department of Political Science Central European University Email: [email protected] MA Programme in Political Science (1 year and 2 years) Doctoral School of Political Science, International Relations and Public Policy Core course Comparative Politics and Political Economy Tracks Winter semester 2020 (4 credits, 8 ECTS credits) Class meetings: XXX Office hours: XXX Introduction to the issue Hybrid regimes that alloy democratic rules with authoritarian governance are the most widespread political systems in the world at the beginning of the 21st century. Conventional accounts describe them as defective democracies or competitive authoritarian regimes. Alternative views point to the genuine features and functions of these regimes that cannot be reduced to those of half-democracies or half-autocracies. In fact, hybrid regimes are puzzling in several ways: (1) their establishment and sustainability have been unexpected either by the school of democratization/transitology or by the school of (new) authoritarianism; (2) neither democratic institutions (e.g. elections) nor autocratic institutions (e.g. dominant parties) function in a conventional way there; and (3) contrary to the expectations of stability, hybrid regimes have demonstrated a variety of (within-type) dynamics. Topics and regional focus In this course, we will seek to unpack the category of hybrid regimes and explore the following questions: What are the origins of hybrid regimes? What are the specifics of their institutional functionality in comparison with democracies and/or autocracies? What determines their durability and dynamic nature? We will review the major research approaches that analyze the political regimes in the ‘grey zone’ between democracy and autocracy and further link these approaches to the broader literature on statehood, economic development and social order. -

What Do We Know About Hybrid Regimes After Two Decades of Scholarship?

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2018, Volume 6, Issue 2, Pages 112–119 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v6i2.1400 Article What Do We Know about Hybrid Regimes after Two Decades of Scholarship? Mariam Mufti Department of Political Science, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, N2L 4M3, Canada; [email protected] Submitted: 31 January 2018 | Accepted: 15 June 2018 | Published: 22 June 2018 Abstract In two decades of scholarship on hybrid regimes two significant advancements have been made. First, scholars have em- phasized that the hybrid regimes that emerged in the post-Cold War era should not be treated as diminished sub-types of democracy, and second, regime type is a multi-dimensional concept. This review essay further contends that losing the lexicon of hybridity and focusing on a single dimension of regime type—flawed electoral competition—has prevented an examination of extra-electoral factors that are necessary for understanding how regimes are differently hybrid, why there is such immense variation in the outcome of elections and why these regimes are constantly in flux. Therefore, a key recommendation emerging from this review of the scholarship is that to achieve a more thorough, multi-dimensional assessment of hybrid regimes, further research ought to be driven by nested research designs in which qualitative and quantitative approaches can be used to advance mid-range theory building. Keywords authoritarianism; classification of regimes; Cold War; dictatorships; elections; hybrid regime Issue This article is part of the issue “Authoritarianism in the 21st Century”, edited by Natasha Ezrow (University of Essex, UK). © 2018 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). -

The Contemporary Debate on Hybrid Regimes and the Identity Question

XXVI Convegno SISP Università Roma Tre – Facoltà di Scienze Politiche Roma, 13-15 Settembre 2012 Panel: “Breakdown of the Authoritarian Regimes and Democracy” Chairs: Giuseppe Ieraci, Fabio Fossati Hybrid what? The contemporary debate on hybrid regimes and the identity question. Andrea Cassani Dept. of Social and Political Studies Università degli Studi di Milano [email protected] Research for this work was funded by a PRIN 2008 project on ‘The effects of democratization on social welfare: a comparative analysis of new democracies’. The project was co-financed by the Italian Ministry of Universities and Research and the Università degli Studi di Milano. This paper is also part of a research project on ‘The economic, social, and political consequences of democratic reforms. A quantitative and qualitative comparative analysis’ (COD), funded by a Starting Grant of the European Research Council (Grant Agreement no. 262873, “Ideas”, 7th Framework Programme of the EU). Abstract After a decade during which the image of an undying and relentless third wave of democratization overshadowed the actual nature of many processes of regime transition throughout the globe, the notion of hybrid regime has finally gained scholars’ attention. Unfortunately, the contemporary launching of different lines of inquiry, along with the rapidity according to which a considerable amount of literature has been published, has resulted in a certain confusion. Because of the scant dialogue of these studies with each other, the current research on hybrid regimes is failing the important goal of building a shared theoretical ground. All this hampers the accumulation of knowledge and undermine the value of future research. -

The Economist Intelligence Unit's Index of Democracy

THE WORLD IN 2OO7 Democracy index 1 The Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy By Laza Kekic, director, country forecasting services, Economist Intelligence Unit Defining and measuring democracy mal sense share at least one common, essential charac- There is no consensus on how to measure democracy, teristic. Positions of political power are fi lled through defi nitions of democracy are contested and there is an regular, free, and fair elections between competing par- ongoing lively debate on the subject. The issue is not ties, and it is possible for an incumbent government only of academic interest. For example, although de- to be turned out of offi ce through elections. Freedom mocracy-promotion is high on the list of American House criteria for an electoral democracy include: foreign-policy priorities, there is no consensus within the American government on what constitutes a de- 1. A competitive, multiparty political system. mocracy. As one observer recently put it, “the world’s 2. Universal adult suffrage. only superpower is rhetorically and militarily promot- 3. Regularly contested elections conducted on the basis ing a political system that remains undefi ned—and it of secret ballots, reasonable ballot security and the is staking its credibility and treasure on that pursuit” absence of massive voter fraud. (Horowitz, 2006, p 114). 4. Signifi cant public access of major political parties to Although the terms “freedom” and “democracy” the electorate through the media and through gener- are often used interchangeably, the two are not syn- ally open campaigning. onymous. Democracy can be seen as a set of practices and principles that institutionalise and thus ultimately The Freedom House defi nition of political freedom is protect freedom. -

Defending Levitsky, Collier and Way's Critique of Illiberal Democracy

Defending Levitsky, Collier and Way’s Critique of Illiberal Democracy: Authoritarianism by Any Other Name Is Still Not a Democracy Kristin Alexy International Policy Network Occasional Paper 3 1 GLOBAL FUTURES Global Futures, a flagship project of the Rutgers University MA Program in Political Science - United Na- tions and Global Policy Studies, is an international association of global policy analysts. By creating a forum for global policy experts, including scholars, practitioners, decision-makers and activists from diverse back- grounds and cultures, Global Futures promotes a constructive international dialogue centered on the chal- lenges we all face as global citizens. Through its publications, conferences and workshops, Global Futures seeks to generate a more comprehensive understanding of contemporary global affairs and, consequently, develop innovative solutions for a more stable, tolerant, and sustainable global society. Benefits of member- ship in Global Futures: • An opportunity for academics, policy-makers, civil society organizations, and business communi- ties to become acquainted with a diverse spectrum of theoretical perspectives, analytical approaches, methodologies and policy prescriptions on global policy issues. • Access to the Global Futures website which contains information on research projects, both ongoing and in formation, funding opportunities for research and training, a discussion board through which to contact colleagues with similar global policy interests, and new publications of interest to the global -

Review Essay Recuperating Radicalism Across Cultures

Middle East Law and Governance 3 (2011) 245–254 brill.nl/melg Review Essay Recuperating Radicalism across Cultures Bruce B. Lawrence Duke University, Durham, N.C. Radicalism and Political Reform in the Islamic and Western Worlds. By Kai Hafez. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 253 pp. ISBN: 978-0- 521-76320-2. US $95.00 (hardcover); ISBN: 978-0-521-13711-9. US $28.99 (paperback) One of the most insistent questions of public policy and academic inquiry since January 2011 has been: Are Islam and democracy compatible in the Arab world? Th e characteristic response was tagged as “Arab Exceptionalism”, referring to the opinion that Arabs had become attuned to authoritarian rule, and that ruling elites opened their parlors or parliaments to popular voices merely as a window dressing to preserve their praetorian, security states from outside criticism. Under this rubric, human rights and civil society existed in the Arab world in name only. Moreover, it was argued, if open elections and participatory government did become possible in majority Muslim Arab countries, it would be those labeled extremists, fundamentalists or Islamists who would come to power, and once in power, they would subvert the very democratic structures that made their rule possible. Many of these same arguments focus on Islam either directly or obliquely. Regarding Islam as inherently patriarchal, and Iran as a test case for Islamic fundamentalism (1978-79)–with Algeria as a sequel (1991)–they have been reviewed in several academic sources, but perhaps nowhere more fully than in Waterbury’s “Democracy Without Democrats: Th e Potential for Political © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2011 DOI 10.1163/187633711X591594 246 B.B. -

Nations in Transit 2020: Dropping the Democratic Facade

NATIONS IN TRANSIT 2020 Dropping the Democratic Facade NATIONS IN TRANSIT 2020 CONTENTS Nations in Transit 2020: Dropping the Democratic Facade ..................... 1 Justice in the Service of Politics ..................................................... 6 Legislatures on the Sidelines ......................................................... 8 Fragile Institutions Open the Door for Chinese Communist Party Influence ........................................... 10 Nations in Transit 2020 Map ............................................................... 12 Eurasia’s Autocrats Grapple with Succession Plans ............................ 14 Within Eco-Protests, Support for Democracy .................................. 16 Recommendations ............................................................................. 18 Nations in Transit 2020 Scores ............................................................ 20 Nations in Transit 2020: Overview of Score Changes ............................. 22 Methodology .................................................................................... 23 Nations in Transit 2020: Category and Democracy Score Summary ......... 24 Nations in Transit 2020: Democracy Score History by Region ................. 25 RESEARCH AND EDITORIAL TEAM This booklet was made possible through the generous support of the U.S. Agency for International Development. The positions of this ON THE COVER publication do not represent the positions of USAID. Serbian police officers escort protesters out of the headquarters The following -

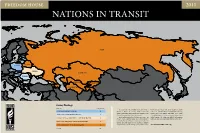

Map of Regime Classifications.Pdf

Freedom House 2011 NAtions iN transit Arctic Ocean Beaufort Sea GREENLAND (DENMARK) ICELAND U.S.A. RUSSIA Hudson Bay ESTONIA Bering Sea Labrador Sea LATVIA RUSSIA LITHUANIA Gulf of Alaska CANADA BELARUS IRELAND POLAND CZECH REP. SLOVAKIA UKRAINE KAZAKHSTAN HUNGARY MOLDOVA North Atlantic Ocean SLOVENIA ROMANIA CROATIA SERBIA BOSNIA & HERZ. BULGARIA MONTENEGRO UZBEKISTAN GEORGIA KYRGYZSTAN KOSOVO MACEDONIA PORTUGAL ALBANIA ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN TURKMENISTAN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA TAJIKISTAN North Pacic Ocean Survey Findings Regime Type Country Breakdown BAHAMAS MEXICO Gulf of Mexico The map reflects the findings of Freedom House’s from year to year. Based on the Democracy Score and its CONSOLIDATED DEMOCRACIES 8 Nations in Transit 2011 survey, which assesses the scale of 1 to 7, Freedom House has defined the following status of democratic development in 29 countries from regime types: consolidated democracy (1–2), semi- SEMI-CONSOLIDATED DEMOCRACIES 6 North Pacic Ocean PUERTO RICO (U.S.A.) Central Europe to Central Asia during 2010. consolidated democracy (3), transitional government/ Freedom House introduced a Democracy Score—an hybrid regime (4), semi-consolidated authoritarian CUBA TRANSITIONAL GOVERNMENTS OR HYBRID REGIMES 5 average of each country’s ratings on all of the indicators regime (5), and consolidated authoritarian regime (6–7). JAMAICA covered by Nations in Transit—beginning with the 2004 ST. KITTS & NEVIS SEMI-CONSOLIDATED AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES 2 edition. The Democracy Score is designed to simplify BELIZE HAITI ANTIGUA & BARBUDA analysis of the countries’ overall progress or deterioration HONDURAS DOM. REP. CONSOLIDATED AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES 8 www.freedomhouse.org DOMINICA Caribbean Sea CAPE VERDE TOTAL 29 GUATEMALA ST. LUCIA MARSHALL GRENADA ST. -

Algeria: a Case Study in Incomplete Democratization

ALGERIA: A CASE STUDY IN INCOMPLETE DEMOCRATIZATION By Allison Gowallis A thesis presented to the faculty of Towson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Social Sciences Department Towson University Towson, MD 21252 (May, 2013) ii Acknowledgements I would like to give special recognition to Dr. Charles Schmitz for being the chair of my thesis committee, guiding me through the process, and having an exceptional knowledge of the Middle East. I would also like to recognize Dr. Matthew Hoddie and Dr. Michael Korzi for being members of my thesis committee and providing me with insight on democracy and related theory. iii Abstract Algeria: A Case Study in Incomplete Democratization Allison Gowallis Algeria is currently a pseudo-democratic state that attempted democratization in the 1980s, but ultimately failed. This thesis investigates how initial democratization began and ended, and how current political characteristics prevent democracy from consolidating. The government gives precedence to elite economic interests over popular interests, an easy task considering the centralization of oil and gas wealth. Under current president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the presidency has become the most powerful authority, escaping executive constraints, and the parliament and political parties are weak and unable to represent diverse interests. Algeria fails to meet all of Robert Dahl’s criteria of a democracy. Given the history of stagnated democratization, it is not likely that Algerians or the government will