Different Effects of Apolipoprotein A5 Snps and Haplotypes on Triglyceride Concentration in Three Ethnic Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variants of Lipid-Related Genes in Adult Japanese Patients with Severe Hypertriglyceridemia Akira Matsunaga1, Mariko Nagashima1, Hideko Yamagishi1 and Keijiro Saku2

The official journal of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society and the Asian Pacific Society of Atherosclerosis and Vascular Diseases Original Article J Atheroscler Thromb, 2020; 27: 1264-1277. http://doi.org/10.5551/jat.51540 Variants of Lipid-Related Genes in Adult Japanese Patients with Severe Hypertriglyceridemia Akira Matsunaga1, Mariko Nagashima1, Hideko Yamagishi1 and Keijiro Saku2 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan 2Department of Cardiology, Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan Aim: Hypertriglyceridemia is a type of dyslipidemia that contributes to atherosclerosis and coronary heart dis- ease. Variants in lipoprotein lipase (LPL), apolipoprotein CII (APOC2), apolipoprotein AV (APOA5), glyco- sylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1), lipase maturation fac- tor 1 (LMF1), and glucokinase regulator (GCKR) are responsible for hypertriglyceridemia. We investigated the molecular basis of severe hypertriglyceridemia in adult patients referred to the Clinical Laboratory at Fukuoka University Hospital. Methods: Twenty-three adult patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (>1,000 mg/dL, 11.29 mmol/L) were selected. The coding regions of candidate genes were sequenced by next-generation sequencing. Forty-nine genes reportedly associated with hypertriglyceridemia were analyzed. Results: In the 23 patients, we detected 70 variants: 28 rare and 42 common ones. Among the 28 rare variants with <1% allele frequency, p.I4533L in APOB, -

Apoa5genetic Variants Are Markers for Classic Hyperlipoproteinemia

CLINICAL RESEARCH CLINICAL RESEARCH www.nature.com/clinicalpractice/cardio APOA5 genetic variants are markers for classic hyperlipoproteinemia phenotypes and hypertriglyceridemia 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 Jian Wang , Matthew R Ban , Brooke A Kennedy , Sonia Anand , Salim Yusuf , Murray W Huff , Rebecca L Pollex and Robert A Hegele1* SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Hypertriglyceridemia is a common biochemical Background Several known candidate gene variants are useful markers for diagnosing hyperlipoproteinemia. In an attempt to identify phenotype that is observed in up to 5% of adults. other useful variants, we evaluated the association of two common A plasma triglyceride concentration above APOA5 single-nucleotide polymorphisms across the range of classic 1.7 mmol/l is a defining component of the meta 1 hyperlipoproteinemia phenotypes. bolic syndrome and is associated with several comorbidities, including increased risk of cardio Methods We assessed plasma lipoprotein profiles and APOA5 S19W and vascular disease2 and pancreatitis.3,4 Factors, –1131T>C genotypes in 678 adults from a single tertiary referral lipid such as an imbalance between caloric intake and clinic and in 373 normolipidemic controls matched for age and sex, all of expenditure, excessive alcohol intake, diabetes, European ancestry. and use of certain medications, are associated Results We observed significant stepwise relationships between APOA5 with hypertriglyceridemia; however, genetic minor allele carrier frequencies and plasma triglyceride quartiles. The factors are also important.5,6 odds ratios for hyperlipoproteinemia types 2B, 3, 4 and 5 in APOA5 S19W Complex traits, such as plasma triglyceride carriers were 3.11 (95% CI 1.63−5.95), 4.76 (2.25−10.1), 2.89 (1.17−7.18) levels, usually do not follow Mendelian patterns of and 6.16 (3.66−10.3), respectively. -

Common Genetic Variations Involved in the Inter-Individual Variability Of

nutrients Review Common Genetic Variations Involved in the Inter-Individual Variability of Circulating Cholesterol Concentrations in Response to Diets: A Narrative Review of Recent Evidence Mohammad M. H. Abdullah 1 , Itzel Vazquez-Vidal 2, David J. Baer 3, James D. House 4 , Peter J. H. Jones 5 and Charles Desmarchelier 6,* 1 Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Kuwait University, Kuwait City 10002, Kuwait; [email protected] 2 Richardson Centre for Functional Foods & Nutraceuticals, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB R3T 6C5, Canada; [email protected] 3 United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N2, Canada; [email protected] 5 Nutritional Fundamentals for Health, Vaudreuil-Dorion, QC J7V 5V5, Canada; [email protected] 6 Aix Marseille University, INRAE, INSERM, C2VN, 13005 Marseille, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The number of nutrigenetic studies dedicated to the identification of single nucleotide Citation: Abdullah, M.M.H.; polymorphisms (SNPs) modulating blood lipid profiles in response to dietary interventions has Vazquez-Vidal, I.; Baer, D.J.; House, increased considerably over the last decade. However, the robustness of the evidence-based sci- J.D.; Jones, P.J.H.; Desmarchelier, C. ence supporting the area remains to be evaluated. The objective of this review was to present Common Genetic Variations Involved recent findings concerning the effects of interactions between SNPs in genes involved in cholesterol in the Inter-Individual Variability of metabolism and transport, and dietary intakes or interventions on circulating cholesterol concen- Circulating Cholesterol trations, which are causally involved in cardiovascular diseases and established biomarkers of Concentrations in Response to Diets: cardiovascular health. -

Additive Effects of LPL, APOA5 and APOE Variant Combinations On

Ariza et al. BMC Medical Genetics 2010, 11:66 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/11/66 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access AdditiveResearch article effects of LPL, APOA5 and APOE variant combinations on triglyceride levels and hypertriglyceridemia: results of the ICARIA genetic sub-study María-José Ariza*1, Miguel-Ángel Sánchez-Chaparro1,2,3, Francisco-Javier Barón4, Ana-María Hornos2, Eva Calvo- Bonacho2, José Rioja1, Pedro Valdivielso1,3, José-Antonio Gelpi2 and Pedro González-Santos1,3 Abstract Background: Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) is a well-established independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and the influence of several genetic variants in genes related with triglyceride (TG) metabolism has been described, including LPL, APOA5 and APOE. The combined analysis of these polymorphisms could produce clinically meaningful complementary information. Methods: A subgroup of the ICARIA study comprising 1825 Spanish subjects (80% men, mean age 36 years) was genotyped for the LPL-HindIII (rs320), S447X (rs328), D9N (rs1801177) and N291S (rs268) polymorphisms, the APOA5- S19W (rs3135506) and -1131T/C (rs662799) variants, and the APOE polymorphism (rs429358; rs7412) using PCR and restriction analysis and TaqMan assays. We used regression analyses to examine their combined effects on TG levels (with the log-transformed variable) and the association of variant combinations with TG levels and hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥ 1.69 mmol/L), including the covariates: gender, age, waist circumference, blood glucose, blood pressure, smoking and alcohol consumption. Results: We found a significant lowering effect of the LPL-HindIII and S447X polymorphisms (p < 0.0001). In addition, the D9N, N291S, S19W and -1131T/C variants and the APOE-ε4 allele were significantly associated with an independent additive TG-raising effect (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, p < 0.0001 and p < 0.001, respectively). -

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in CETP, SLC46A1, SLC19A1, CD36

Clifford et al. Lipids in Health and Disease 2013, 12:66 http://www.lipidworld.com/content/12/1/66 RESEARCH Open Access Single nucleotide polymorphisms in CETP, SLC46A1, SLC19A1, CD36, BCMO1, APOA5,andABCA1 are significant predictors of plasma HDL in healthy adults Andrew J Clifford1*, Gonzalo Rincon2, Janel E Owens3, Juan F Medrano2, Alanna J Moshfegh4, David J Baer5 and Janet A Novotny5 Abstract Background: In a marker-trait association study we estimated the statistical significance of 65 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in 23 candidate genes on HDL levels of two independent Caucasian populations. Each population consisted of men and women and their HDL levels were adjusted for gender and body weight. We used a linear regression model. Selected genes corresponded to folate metabolism, vitamins B-12, A, and E, and cholesterol pathways or lipid metabolism. Methods: Extracted DNA from both the Sacramento and Beltsville populations was analyzed using an allele discrimination assay with a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry platform. The adjusted phenotype, y, was HDL levels adjusted for gender and body weight only statistical analyses were performed using the genotype association and regression modules from the SNP Variation Suite v7. Results: Statistically significant SNP (where P values were adjusted for false discovery rate) included: CETP (rs7499892 and rs5882); SLC46A1 (rs37514694; rs739439); SLC19A1 (rs3788199); CD36 (rs3211956); BCMO1 (rs6564851), APOA5 (rs662799), and ABCA1 (rs4149267). Many prior association trends of the SNP with HDL were replicated in our cross-validation study. Significantly, the association of SNP in folate transporters (SLC46A1 rs37514694 and rs739439; SLC19A1 rs3788199) with HDL was identified in our study. -

Genetic Association of APOA5 and APOE with Metabolic Syndrome And

Son et al. Lipids in Health and Disease (2015) 14:105 DOI 10.1186/s12944-015-0111-5 RESEARCH Open Access Genetic association of APOA5 and APOE with metabolic syndrome and their interaction with health-related behavior in Korean men Ki Young Son1,6†, Ho-Young Son2†, Jeesoo Chae3, Jinha Hwang3, SeSong Jang3, Jae Moon Yun1,6, BeLong Cho1,6, Jin Ho Park1,6* and Jong-Il Kim2,3,4,5* Abstract Background: Genome-wide association studies have been used extensively to identify genetic variants linked to metabolic syndrome (MetS), but most of them have been conducted in non-Asian populations. This study aimed to evaluate the association between MetS and previously studied single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and their interaction with health-related behavior in Korean men. Methods: Seventeen SNPs were genotyped and their association with MetS and its components was tested in 1193 men who enrolled in the study at Seoul National University Hospital. Results: We found that rs662799 near APOA5 and rs769450 in APOE had significant association with MetS and its components. The SNP rs662799 was associated with increased risk of MetS, elevated triglyceride (TG) and low levels of high-density lipoprotein, while rs769450 was associated with a decreased risk of TG. The SNPs showed interactions between alcohol drinking and physical activity, and TG levels in Korean men. Conclusions: We have identified the genetic association and environmental interaction for MetS in Korean men. These results suggest that a strategy of prevention and treatment should be tailored to personal genotype and the population. Keywords: APOA5, APOE, Health behavior, Metabolic syndrome, Triglyceride Background MetS is caused by multiple genetic and environmental According to a World Health Organization report, car- risk factors, and an interaction between the factors has diovascular diseases were the cause of 30 % of all deaths been widely postulated. -

Common Variants in the Genes of Triglyceride and HDL-C Metabolism Lack Association with Coronary Artery Disease in the Pakistani Subjects Saleem Ullah Shahid1*, N.A

Shahid et al. Lipids in Health and Disease (2017) 16:24 DOI 10.1186/s12944-017-0419-4 RESEARCH Open Access Common variants in the genes of triglyceride and HDL-C metabolism lack association with coronary artery disease in the Pakistani subjects Saleem Ullah Shahid1*, N.A. Shabana1, Jackie A. Cooper2, Abdul Rehman1 and Steve E. Humphries2 Abstract Background: Serum Triglyceride (TG) and High Density Lipoprotein (HDL-C) levels are modifiable coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors. Polymorphisms in the genes regulating TG and HDL-C levels contribute to the development of CAD. The objective of the current study was to investigate the effect of four such single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) in the genes for Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL) (rs328, rs1801177), Apolipoprotein A5 (APOA5) (rs66279) and Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) (rs708272) on HDL-C and TG levels and to examine the association of these SNPs with CAD risk. Methods: A total of 640 subjects (415 cases, 225 controls) were enrolled in the study. The SNPs were genotyped by KASPar allelic discrimination technique. Serum HDL-C and TG were determined by spectrophotometric methods. Results: The population under study was in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium and minor allele of SNP rs1801177 was completely absent in the studied subjects. The SNPs were association with TG and HDL-C levels was checked through regression analysis. For rs328, the effect size of each risk allele on TG and HDL-C (mmol/l) was 0.16(0.08) and −0.11(0.05) respectively. Similarly, the effect size of rs662799 for TG and HDL-C was 0.12(0.06) and −0.13(0.0.3) and that of rs708272 was 0.08(0.04) and 0.1(0.03) respectively. -

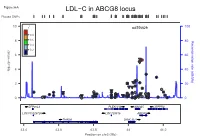

LDL−C in ABCG8 Locus Plotted Snps

Figure S6A LDL−C in ABCG8 locus Plotted SNPs 10 r2 rs6756629 100 0.8 8 0.6 80 (cM/Mb) Recombination rate 0.4 0.2 6 60 (p−value) 10 4 40 log − ● ● ● ● 2 20 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ●● ● ●● ● 0 ● ● ● ● ●●● ● ● 0 ZFP36L2 PLEKHH2 ABCG5 LRPPRC LOC100129726 LOC728819 ABCG8 THADA DYNC2LI1 43.4 43.6 43.8 44 44.2 Position on chr2 (Mb) Figure S6B LDL−C in ABCG8 locus Conditional Analysis Plotted SNPs 10 r2 rs6756629 100 0.8 8 0.6 80 (cM/Mb) Recombination rate 0.4 0.2 6 60 (p−value) 10 4 40 log − ● ● ● 2 ● 20 ● ● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ●● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ● ●●● ● ● ● ●● ● ● 0 ● ● ● ● ●● ●● ● ● 0 ZFP36L2 PLEKHH2 ABCG5 LRPPRC LOC100129726 LOC728819 ABCG8 THADA DYNC2LI1 43.4 43.6 43.8 44 44.2 Position on chr2 (Mb) Figure S6C FG in G6PC2 locus Plotted SNPs 2 r rs560887 100 ●● 10 0.8 0.6 80 0.4 (cM/Mb) Recombination rate 8 0.2 60 6 (p−value) 10 ● log 40 − 4 ● 2 20 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ●● ● 0 ●● ● 0 CERS6 NOSTRIN G6PC2 DHRS9 MIR4774 CERS6−AS1 SPC25 ABCB11 169.3 169.4 169.5 169.6 169.7 169.8 169.9 Position on chr2 (Mb) Figure S6D FG in G6PC2 locus Conditional Analysis Plotted SNPs 2 10 r rs560887 100 0.8 0.6 8 80 0.4 (cM/Mb) Recombination rate 0.2 6 60 ● (p−value) 10 log 4 40 − 2 20 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●●● ● 0 ●● ●●● 0 CERS6 NOSTRIN G6PC2 DHRS9 MIR4774 CERS6−AS1 SPC25 ABCB11 169.3 169.4 169.5 169.6 169.7 169.8 169.9 Position on chr2 (Mb) Figure S6E HDL−C in LPL locus Plotted SNPs 2 10 r rs10096633 100 0.8 0.6 8 0.4 80 Recombination rate (cM/Mb) Recombination rate 0.2 ● 6 ●● 60 (p−value) 10 log 4 40 − 2 20 ● ● ● ● ● ● 0 ● ●● 0 LPL 19.79 19.8 -

Dyslipidemia Infosheet 6-10-19

Genetic Testing for Dyslipidemias Clinical Features: Dyslipidemias are a clinically and genetically heterogenous group of disorders associated with abnormal levels of lipids and lipoproteins, including increased or decreased levels of LDL or HDL cholesterol or increased levels of triglycerides [1]. Dyslipidemias can have a monogenic cause, or may be associated with other conditions such as diabetes and thyroid disease, or lifestyle factors. The most common subset of monogenic dyslipidemia is familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), which has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 200 in the Caucasian population [2]. Our Dyslipidemia Panes includes analysis of all 23 genes listed below. Dyslipidemia Panel Genes ABCA1 APOA1 CETP LDLR LMF1 SAR1B ABCG5 APOA5 GPD1 LDLRAP1 LPL SCARB1 ABCG8 APOB GPIHBP1 LIPA MTTP STAP1 ANGPTL3 APOC2 LCAT LIPC PCSK9 Gene OMIM# Associated disorders Dyslipidemia Inheritance Reference phenotype s ABCA1 60004 Tangier disease; High Low HDL-C Recessive; [3, 4] 6 density lipoprotein (HDL) Dominant deficiency ABCG5 60545 Sitosterolemia Hypercholesterolemia Recessive [5] 9 , hypersitosterolemia ABCG8 60546 Sitosterolemia Hypercholesterolemia Recessive [5] 0 , hypersitosterolemia ANGPTL 60501 Familial Low LDL-C Recessive [6] 3 9 hypobetalipoproteinemia- 2 APOA1 10768 Apolipoprotein A-I Low HDL-C Recessive; [7, 8] 0 deficiency; HDL Dominant deficiency APOA5 60636 Hyperchylomicronemia; Hypertriglyceridemia Dominant/Recessive [9, 10] 8 Hypertriglyceridemia ; Dominant APOB 10773 Familial High LDL-C; Low Co-dominant [1, 11] 0 hypercholesterolemia; -

Remnants of the Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease

508 Diabetes Volume 69, April 2020 Remnants of the Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease Alan Chait,1 Henry N. Ginsberg,2 Tomas Vaisar,1 Jay W. Heinecke,1 Ira J. Goldberg,3 and Karin E. Bornfeldt1,4 Diabetes 2020;69:508–516 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dbi19-0007 Diabetes is now a pandemic disease. Moreover, a large LDL-C levels by increasing LDL receptor activity are widely number of people with prediabetes are at risk for de- used to prevent CVD. However, despite the benefitof veloping frank diabetes worldwide. Both type 1 and type statins and marked reduction of circulating LDL-C levels, 2 diabetes increase the risk of atherosclerotic cardio- patients with diabetes continue to have more CVD events vascular disease (CVD). Even with statin treatment to than patients without diabetes, indicating significant re- lower LDL cholesterol, patients with diabetes have a high sidual CVD risk. A recent new classification system of residual CVD risk. Factors mediating the residual risk are T2DM, based on different patient characteristics and risk of incompletely characterized. An attractive hypothesis is diabetes complications, divides adults into five different that remnant lipoprotein particles (RLPs), derived by clusters of diabetes (3). Such a substratification of T2DM, lipolysis from VLDL and chylomicrons, contribute to this which takes insulin resistance and several other factors into residual risk. RLPs constitute a heterogeneous popula- account, could perhaps help tailor treatment to those who tion of lipoprotein particles, varying markedly in size and would benefit the most. composition. Although a universally accepted definition fi There are likely to be a number of reasons why cho- is lacking, for the purpose of this review we de ne RLPs fi as postlipolytic partially triglyceride-depleted particles lesterol reduction in patients with diabetes is not suf cient derived from chylomicrons and VLDL that are relatively to reduce CVD events to the levels found in patients enriched in cholesteryl esters and apolipoprotein (apo)E. -

Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP1) Is

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Low‑density lipoprotein receptor‑related protein 1 (LRP1) is a novel receptor for apolipoprotein A4 (APOA4) in adipose tissue Jie Qu1, Sarah Fourman1, Maureen Fitzgerald1, Min Liu1, Supna Nair2, Juan Oses‑Prieto2, Alma Burlingame2, John H. Morris2, W. Sean Davidson1, Patrick Tso1 & Aditi Bhargava3* Apolipoprotein A4 (APOA4) is one of the most abundant and versatile apolipoproteins facilitating lipid transport and metabolism. APOA4 is synthesized in the small intestine, packaged onto chylomicrons, secreted into intestinal lymph and transported via circulation to several tissues, including adipose. Since its discovery nearly 4 decades ago, to date, only platelet integrin αIIbβ3 has been identifed as APOA4 receptor in the plasma. Using co‑immunoprecipitation coupled with mass spectrometry, we probed the APOA4 interactome in mouse gonadal fat tissue, where ApoA4 gene is not transcribed but APOA4 protein is abundant. We demonstrate that lipoprotein receptor‑related protein 1 (LRP1) is the cognate receptor for APOA4 in adipose tissue. LRP1 colocalized with APOA4 in adipocytes; it interacted with APOA4 under fasting condition and their interaction was enhanced during lipid feeding concomitant with increased APOA4 levels in plasma. In 3T3‑L1 mature adipocytes, APOA4 promoted glucose uptake both in absence and presence of insulin in a dose‑dependent manner. Knockdown of LRP1 abrogated APOA4‑induced glucose uptake as well as activation of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)‑mediated protein kinase B (AKT). Taken together, we identifed LRP1 as a novel receptor for APOA4 in promoting glucose uptake. Considering both APOA4 and LRP1 are multifunctional players in lipid and glucose metabolism, our fnding opens up a door to better understand the molecular mechanisms along APOA4‑LRP1 axis, whose dysregulation leads to obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. -

Understanding Lipid Metabolism and Its Link to Diseases Beyond

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/457960; this version posted October 31, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Genetics of human plasma lipidome: Understanding lipid metabolism and its link to diseases beyond traditional lipids Rubina Tabassum1, Joel T. Rämö1, Pietari Ripatti1, Jukka T. Koskela1, Mitja Kurki1,2,3, Juha Karjalainen1,4,5, Shabbeer Hassan1, Javier Nunez-Fontarnau1, Tuomo T.J. Kiiskinen1, Sanni Söderlund6, Niina Matikainen6,7, Mathias J. Gerl8, Michal A. Surma8,9, Christian Klose8, Nathan O. Stitziel10,11,12, Hannele Laivuori1,13,14, Aki S. Havulinna1,15, Susan K. Service16, Veikko Salomaa15, Matti Pirinen1,17,18, FinnGen Project, Matti Jauhiainen15,19, Mark J. Daly1,4, Nelson B. Freimer16, Aarno Palotie1,4,20, Marja-Riitta Taskinen6, Kai Simons8,21, and Samuli Ripatti1,4,22* 1Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland, HiLIFE, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland; 2Program in Medical and Population Genetics and Genetic Analysis Platform, Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA; 3Psychiatric & Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 4Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA; 5Analytic and Translational Genetics Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital