Latino Voting in the 2004 Election: the Case of New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TLC Pilot to Add More EV Taxi Models How to Tell If Your Car Is Burning

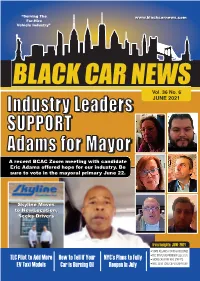

“Serving The www.blackcarnews.comwww.blackcarnews.com For-Hire Vehicle Industry” Vol. 36 No. 6 IIndustryndustry LLeaderseaders JUNE 2021 SSUPPORTUPPORT AAdamsdams fforor MMayorayor A recent BCAC Zoom meeting with candidate Eric Adams offered hope for our industry. Be sure to vote in the mayoral primary June 22. Skyline Moves to NewLocation, SeeksSeeks DriversDrivers Ira’s Insights: JUNE 2021 • STATE RELAXES COVID GUIDELINES • THE MAYORAL PRIMARY ELECTION TLC Pilot to Add More How to Tell if Your NYC’s Plans to Fully • MORE CAR-FREE NYC STREETS EV Taxi Models Car is Burning Oil Reopen in July • WILL BEVS LOSE CAP EXEMPTION? 2 • BLACK CAR NEWS • JUNE 2021 JUNE 2021 • BLACK CAR NEWS Attention NYC • 3 FHV Drivers: If You’re Not Leasing or Renting From City Livery Leasing, Then You are in the Wrong Place! Voted #1 Leasing We Were Voted #1 in NYC and Here is Why: Company • Best customer service team with 4 convenient locations in NYC • Best Overall Pricing and Deal Terms for Both Lease-to-Own and Rentals • Fastest Insurance Approvals in the Business • Easy Access Website for ALL Your Required Paperwork Incredible WAVs Get Started NOW! Starting at www.cityliveryleasing.com ONLY $ Come experience what your fellow drivers already know – 300 /week City Livery Leasing is the partner that invests in your success! Visit City Livery Leasing, where you are always treated with the respect and care that you deserve. Choose From 4 Convenient Locations: Bronx 1765 Carter Ave. Bronx 2nd Floor 4309 3rd Ave. Brooklyn Bronx, NY 10457 (at the corner of 179th St.) 270 43rd St. -

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 Printed On: 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Democratic Party Nominations for the following offices and positions: Mayor Public Advocate City Comptroller Borough President District Attorney Member of the City Council Judge of the Civil Court - District Female District Leader Female District Leader Male District Leader Delegate to Judicial Convention Alternate Delegate to the Judicial Convention Page 2 of 17 BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Mayor - Citywide Aaron S. Foldenauer 90 Washington Street New York, NY 10006 Dianne Morales 200 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Scott M. Stringer 25 Broad Street 12S New York, NY 10004 Raymond J. McGuire 145 Central Park West New York, NY 10023 Maya D. Wiley 1519 Albemarle Road Brooklyn, NY 11226 Paperboy Love Prince 852 Monroe Street 3 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Art Chang 384 Sterling Place Brooklyn, NY 11238 Kathryn A. Garcia 591 Carroll Street Brooklyn, NY 11215 Eric L. Adams 936 Lafayette Avenue FL 1 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Isaac Wright Jr. 785 Seneca Avenue Ridgewood, NY 11385 Shaun Donovan 139 Bond Street Brooklyn, NY 11217 Andrew Yang 650 West 42 Street New York, NY 10036 Joycelyn Taylor 153 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Public Advocate - Citywide Anthony L. -

GOP Lawmakers Are Pushing Bills on the Maryland Democratic Sen

the skiff x 360 . volume 114 . issue 29 . www.tcu360.com . all tcu. all the time. april 14 . 2016 ski x 360 T H E S K I F F B Y T C U 3 6 0 Music to children's ears Students organize first SpringFest to benefit Cook Children’s 8 & 9 INSIDE : CAMPUS BOOKSTORE CHANGES 6 - SPORTS ROUND-UP 11 - FORT WORTH REFUGEE RESETTLEMENT 12 - FREE FROG CAMPS 16 2 skiff x 360 · www.tcu360.com all tcu. all the time. april 14 · 2 0 1 6 campus construction riff ram, instagram! Water line replacement begins on Bellaire Drive North By Kristen Weaver of strategic internal communications. [email protected] New construction is happening in two phases, Hulme wrote. Construction around TCU’s campus Phase 1 represents work along won’t be ending anytime soon. Bellaire Drive North to the intersection The Fort Worth Water Department of Alton Drive. is working on expanding water lines Phase 2 represents work from Alton on Bellaire Drive North beginning Drive to Bellaire Drive West. The Thursday. It is expected to be under water line construction won’t close construction for approximately 90 any parking lots around TCU. Lots days, until early July. 2, 11, and the Physical Plant lot will Last semester, the water remain open throughout the water line department replaced pipes across construction, according to Hulme. University Drive, which caused road At times during construction, @TCU_ATHLETICS closures and traffic buildups for a few Bellaire Drive will be limited to a BASEBALL In celebration of another baseball weekend, TCU athletics posted this months. -

2021 NYC Republican Mayoral Primary Unofficial 1St Round Results

Woodlawn- 2021 NYC Republican Mayoral Primary Wakefield Riverdale unofficial 1st round results by Election District Van Cortlandt Co-op as of June 24 Village City The Bronx **OMITS ABSENTEE BALLOTS** Washington Hts Parkchester Curtis A. Sliwa Fernando Mateo Write In Votes Share Votes Share Votes Share BORO TOTAL Manhattan 4,112 65.1% 1,758 27.8% 447 7.1% 6,317 100.0% Bronx 1,723 57.9% 1,094 36.8% 158 5.3% 2,975 100.0% Central Harlem Hunts Brooklyn 8,203 73.0% 2,409 21.4% 620 5.5% 11,232 100.0% Mott Haven-Port Point Queens 10,871 69.5% 4,180 26.7% 580 3.7% 15,631 100.0% Morris Upper Staten Island 11,963 69.0% 4,951 28.5% 429 2.5% 17,343 100.0% West Side n East Rikers a Harlem NYC TOTAL 36,872 68.9% 14,392 26.9% 2,234 4.2% 53,498 100.0% t Island Whitestone t a Bay Terrace- h College Clearview n Steinway a Upper Point East Murray Vote share by election district M Side Hill Bayside Clinton East Astoria Elmhurst for each candidate Jackson Flushing East Heights Flushing Size of each pie chart represents Corona Elmhurst Queens Corona Oakland total GOP primary votes per Election District Gardens West Bellerose Village Rego (ED 65 in Assembly district 62 on Staten Island Greenpoint Maspeth Park Kew Gardens Queens has the most votes: 150) Middle Forest Hills Village Hills Village Kew Ridgewood Jamaica Hollis Curtis Sliwa Glendale Gardens Williamsburg Fernando Mateo Bushwick South Richmond South Hill Jamaica St. -

Download This File

396 HAQJSEA1 Kalter - direct 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK 2 ------------------------------x 3 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 4 v. 16 Cr. 467 ALC 5 NORMAN SEABROOK AND MURRAY HUBERFELD, 6 Defendants. 7 ------------------------------x 8 9 10 October 26, 2017 9:00 a.m. 11 12 13 Before: 14 HON. ANDREW L. CARTER, JR., 15 District Judge and a jury 16 17 18 APPEARANCES 19 JOON H. KIM, United States Attorney for the 20 Southern District of New York KAN MIN NAWADAY, 21 MARTIN S. BELL, RUSSELL CAPONE, 22 Assistant United States Attorneys 23 24 25 SOUTHERN DISTRICT REPORTERS, P.C. (212) 805-0300 535 HAQJSEA5 Rechnitz - direct 1 Government Exhibits 202 through 207, 209 and 210 into evidence. 2 THE COURT: That is in. 3 (Government Exhibits 1502, 202 through 207, 209 and 4 210 received in evidence) 5 MR. BELL: Your Honor, the government calls Jona 6 Rechnitz. 7 JONA SOLOMON RECHNITZ, 8 called as a witness by the Government, 9 having been duly sworn, testified as follows: 10 DIRECT EXAMINATION 11 BY MR. BELL: 12 Q. Good afternoon, Mr. Rechnitz. 13 A. Good afternoon. 14 Q. Where were you born? 15 A. Los Angeles, California. 16 Q. Where do you live now? 17 A. Los Angeles, California. 18 THE COURT: Let me ask the witness to lean into the 19 microphone so we can hear you. Can the jury hear okay? Keep 20 your voice up. 21 BY MR. BELL: 22 Q. I will try to lead by example, Mr. Rechnitz. 23 How old are you now? 24 A. -

NEW YORK CITY MAYORAL CANDIDATE VOTER GUIDE: HOMELESSNESS & HOUSING TABLE of CONTENTS 01 Introduction

NEW YORK CITY MAYORAL CANDIDATE VOTER GUIDE: HOMELESSNESS & HOUSING TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Introduction 04 About RxHome 06 How to Use this Voter Guide 10 Summary of Mayoral Candidate Policy Platforms 17 Candidate Responses to RxHome’s Mayoral Questionnaire 70 How to Register and Vote in the 2021 NYC Municipal Election 75 List of Acronyms & Glossary 78 Additional Resources 80 Acknowledgements i N N N O O O I I I T T T C C C U U U D D D O O O R R R T T T N N N I I I Introduction How Your Vote Can End Homelessness This year’s election will be unlike any other in New York City history. The implementation of ranked choice voting—in tandem with the impact of the pandemic on our city’s civic fabric, the massive turnover in city government leadership due to term limits and the uncharacteristically large field of candidates vying for mayor—creates an unprecedented opportunity for civic engagement to spur long-term change. Voting in both the primary and general elections can ensure that our next elected leaders commit to ending homelessness. New York City needs a leader who will create the structures and systems that prioritize permanent housing over emergency shelter, ultimately making homelessness a rare, brief and nonrecurring experience for New Yorkers. Even with more than 8.4 million people in New York City, each voter’s voice matters. In 2013—the last mayoral election year without an incumbent—only 22% of registered Democratic voters (fewer than 700,000 people) participated in the primary election. -

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 Printed On: 6/11/2021 11:15:39AM BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/11/2021 11:15:39AM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Democratic Party Nominations for the following offices and positions: Mayor Public Advocate City Comptroller Borough President District Attorney Member of the City Council Judge of the Civil Court - District Female District Leader Female District Leader Male District Leader Delegate to Judicial Convention Alternate Delegate to the Judicial Convention Page 2 of 17 BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/11/2021 11:15:39AM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Mayor - Citywide Aaron S. Foldenauer 90 Washington Street New York, NY 10006 Dianne Morales 200 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Scott M. Stringer 25 Broad Street 12S New York, NY 10004 Raymond J. McGuire 145 Central Park West New York, NY 10023 Maya D. Wiley 1519 Albemarle Road Brooklyn, NY 11226 Paperboy Love Prince 852 Monroe Street 3 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Art Chang 384 Sterling Place Brooklyn, NY 11238 Kathryn A. Garcia 591 Carroll Street Brooklyn, NY 11215 Eric L. Adams 936 Lafayette Avenue FL 1 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Isaac Wright Jr. 785 Seneca Avenue Ridgewood, NY 11385 Shaun Donovan 139 Bond Street Brooklyn, NY 11217 Andrew Yang 650 West 42 Street New York, NY 10036 Joycelyn Taylor 153 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Public Advocate - Citywide Anthony L. -

Results Book

q DALLASDALLAS MARATHONMARATHON 2004 Dallas White Rock Marathon Benefi tingTexas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children Sunday. December 11. 2005 a.-ooam RUN he ROCkl DALLAS whne R~k MARATHON :2.005 Amedc:on Alrlne, Center - VlctGly Plozo, Doll•, lexos Pu■ MGrathon • Hal M<lroltlon • 5-1'- 11-'<ly Lalla• 1'111• MOMY l'urs. - hit l!!q>o In 1M Soultlw..t Mote than ao land& Along a Scenic Coul'H www.runtherocllc.com !Mn.at, T II; X A ■ SCOTTISH RITE HOSPITAL Cl 11·.. lllllllllti 17> Salute to Pat Cheshier The runners and supporters of the Dallas White Rock Marathon owe a debt of gratitude to countless family, friends and volunteers who make behind-the-scenes contributions that help The Rock run. At the top of that 2 Dear Runners list is Pat Cheshier, recently retired 5 Dallas Police Association Senior Corporal from the Dallas Police Department. Pat is a 33-year veteran 6 The Course of the DPD and served as head of 8 Texas Shindig the Special Operations Division of the DPD since 1991. For the past 14 10 Hall of Fame years, Pat has been personally responsible for the safety of our runners, and 11 Top Finishers virtually every other running event in the City of Dallas. 13 Victory Award for Excellence Pat and his colleagues at the Dallas Police Department are heroes to those of us 14 For The Love of The Lake who run. We are particularly proud that the Dallas Police Association has, for the second year, donated their services to the Dallas White Rock Marathon so that 15 A Day at TSRH the Marathon could contribute more money to the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for 16 Fitness Expo Children. -

1 1 2 3 4 5 NEW YORK CITY TAXI and LIMOUSINE COMMISSION 6 MEETING Held on Tuesday, March 30, 2004 7

1 1 2 3 4 5 NEW YORK CITY TAXI AND LIMOUSINE COMMISSION 6 MEETING held on Tuesday, March 30, 2004 7 at 40 Rector Street 8 New York, New York 9 10 11 MATTHEW DAUS, COMMISSIONER/CHAIR 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 TANKOOS REPORTING COMPANY, INC. 305 Madison Avenue 142 Willis Avenue 24 Suite 449 P.O. Box 347 New York, N.Y. 10165 Mineola, N.Y. 11501 25 (212)349-9692 (516)741-5235 (212) 349-9692 TANKOOS REPORTING COMPANY (516) 741-5235 2 1 APPEARANCES: 2 ELIAS AROUT, Commissioner NOACH DEAR, Commissioner 3 HARRY GIANNOULIS, Commissioner STANLEY E. MICHELS, Commissioner 4 HARRY RUBINSTEIN, Commissioner ELLIOT SANDER, Commissioner 5 ALBERTO TORRES, Commissioner IRIS WEINSHALL, Commissioner 6 PETER M. MAZER, General Counsel 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 (212) 349-9692 TANKOOS REPORTING COMPANY (516) 741-5235 3 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 (9:30 a.m.) 3 CHAIRMAN DAUS: Good morning, I want to 4 thank everybody for coming this morning. I am going 5 to give you a brief description of the agenda for 6 today and then we will commence the public hearing 7 process on the rule making before the Commission 8 today. We have gone through a very long process to 9 get to this point and we have some major decisions 10 to discuss today. There are many people in this 11 room who contributed to this process which has led 12 to good, well thought out rules, and I want to thank 13 you for your participation. -

Matthew W. Daus Monthly Column

Matthew W. Daus, Esq. President, International Association of Transportation Regulators http://iatr.global/ Transportation Technology Chair, City University of New York, Transportation Research Center at The City College of New York http://www.utrc2.org/ Partner and Chairman, Windels Marx Transportation Practice Group http://windelsmarx.com Contact: [email protected] 156 West 56th Street | New York, NY 10019 T. 212.237.1106 | F. 212.262.1215 {11929928:1} 1 The 2021 NYC Mayoral Election: What Candidates Are Saying About Transportation Issues & What the Next Mayor Should Do! During the primary election on June 22, New Yorkers will have a say in how the City moves forward from the pandemic. Every citywide office is on the ballot, including Mayor. As usual, the mayoral field is crowded. The leading Democratic contenders currently registering in the polls are Eric Adams, Shaun Donovan, Kathryn Garcia, Ray McGuire, Dianne Morales, Scott Stringer, Maya Wiley, and Andrew Yang. In addition, there are two Republican candidates: Fernando Mateo and Curtis Sliwa. Regardless of who wins, Bill de Blasio’s successor will have to deal with the pandemic’s aftermath, as well the unprecedented economic disruption it has wrought on New Yorkers and the City. Among the many policy decisions the new mayor must make will be those affecting transportation—or, as it has been variously referred to by the candidates, the “central nervous system,” “heartbeat,” and “lifeblood” of the City. From busways, bike lanes, and Open Streets to traffic congestion, Vision Zero, aggressive emissions and climate-change goals, the next mayor will shape the way people and goods move around the City for years to come. -

Your Guide to the 2021 Primary Elections by Jacob Kaye Queens Daily Eagle the 2021 Citywide Primary Elections Are Fi- Nally Here

VolumeVol.Volume 66, No. 65,65, 80 No.No. 207207 MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARYFEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10,10, 2020 20202020 50¢ A tree fell across wires in Queens Village, knocking out power and upending a chunk of sidewalk. VolumeQUEENSQUEENS 65, No. 207 LIGHTSMONDAY, OUT FEBRUARY 10, 2020 Photo by Teresa Mettela 50¢ 57,000 QueensQueensQueens residents lose power Vol.VolumeVolume 66, No. 65, 65, 80 No. No. 207 207 MONDAY,MONDAY, FEBRUARY FEBRUARY 10, 10, 2020 2020 50¢50¢ VolumeVolumeVol.VolumeVol. 66,66,67, 65, No. No.65,65, No. 80 8047No.No. 207 207207 MONDAY,THURSDAY,MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY,MONDAY, FEBRUARY FEBRUARYFEBRUARYFEBRUARY AUGUST AUGUSTJUNEAUGUST 21, 6,10, 6,10,20216,10, 10,2020 20202020 20202020 50¢50¢50¢ Volume 65, No. 207 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2020 50¢ VolumeVol.TODAY 66, No.65, 80No. 207 MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10, 2020 2020 A tree fell across wires in50¢ TODAY AA tree tree fell fell across across wires wires in in TODAY QueensQueensQueens Village, Village, Village, knocking knocking knocking Cityout outCouncilout power power power and and and upending upending upending A treeaa chunka chunkfell chunk across of of ofsidewalk. sidewalk. sidewalk.wires in VolumeVolumeVolumeQUEENSQUEENSQUEENSQUEENS 65, 65,65, No. No.No. 207 207207 LIGHTSLIGHTSduring intenseMONDAY,MONDAY, OUTOUTOUT FEBRUARY FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 10, 10,10, 2020 20202020 QueensPhotoPhoto PhotoVillage, by by byTeresa Teresa Teresa knocking Mettela Mettela Mettela 50¢50¢50¢ QUEENS out power and upending 57,00057,000 Queens QueensQueensQueensQueensQueens bill -

Police Chief in the Garden by George Capsis Who Made the Wrong Decision When Asked to Get Off the Neck of the Subject of His Ar- “I Would Like to Come and See You, Mr

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 17, NUMBER 5 MAY 2021 $2.00 Police Chief in the Garden By George Capsis who made the wrong decision when asked to get off the neck of the subject of his ar- “I would like to come and see you, Mr. Cap- rest. Just maybe, Silverstein thought, our sis” Alan Silverstein excitedly offered on the paper could become the voice of the police. phone. He came in ten minutes and parked Alan, as we have come to call him, con- in front of my Charles Street door with li- tinually juggles the names of top cops that cense plates that allow him to park at the are his buddies, so we asked him to arrange steps of City Hall. Holding a copy of West- for us to interview one. He not only got View News—that had the anti-graffiti pro- a top cop to agree, he brought him to our gram on its front cover—he was excited. garden at 69 Charles (amazing!). I learned later that Alan Silverstein is Chief Sal Comodo and Police Officer one of the most active volunteers of Com- (PO) Natasha DeLeon from NYPD head- munity Partners, a civilian organization quarters, both with relaxed soft smiles, ar- working with the police's Neighborhood rived to discuss the 4/10/21 anti-graffiti Coordination Officers (NCO) division— event and how we could keep the momen- which is, of course, now very much needed. tum moving, now that every precinct was no Here was WestView News, a communi- longer on “lockdown.” ty newspaper vigorously supporting a city- PO Natasha DeLeon, with a relaxed wide police effort that has the police and GEORGE CAPSIS MET WITH NYPD CHIEF SAL COMODO AND PO NATASHA DELEON, tone, told of rolling paint over graffiti with civilians side-by-side painting out graf- ARRANGED BY ALAN SILVERSTEIN (far right), with Bruce and Suzanne Poli, Dusty Berke children from a local school, feeling that fiti, and doing it as the whole country was and Brian Pape of WestView News, to discuss the 4/10/21 anti-graffiti event, and ways to this was all that was needed.