Tenzing Norgay 1914-1986 and the Sherpa Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vividh Bharati Was Started on October 3, 1957 and Since November 1, 1967, Commercials Were Aired on This Channel

22 Mass Communication THE Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, through the mass communication media consisting of radio, television, films, press and print publications, advertising and traditional modes of communication such as dance and drama, plays an effective role in helping people to have access to free flow of information. The Ministry is involved in catering to the entertainment needs of various age groups and focusing attention of the people on issues of national integrity, environmental protection, health care and family welfare, eradication of illiteracy and issues relating to women, children, minority and other disadvantaged sections of the society. The Ministry is divided into four wings i.e., the Information Wing, the Broadcasting Wing, the Films Wing and the Integrated Finance Wing. The Ministry functions through its 21 media units/ attached and subordinate offices, autonomous bodies and PSUs. The Information Wing handles policy matters of the print and press media and publicity requirements of the Government. This Wing also looks after the general administration of the Ministry. The Broadcasting Wing handles matters relating to the electronic media and the regulation of the content of private TV channels as well as the programme matters of All India Radio and Doordarshan and operation of cable television and community radio, etc. Electronic Media Monitoring Centre (EMMC), which is a subordinate office, functions under the administrative control of this Division. The Film Wing handles matters relating to the film sector. It is involved in the production and distribution of documentary films, development and promotional activities relating to the film industry including training, organization of film festivals, import and export regulations, etc. -

An Indian Englishman

AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN MEMOIRS OF JACK GIBSON IN INDIA 1937–1969 Edited by Brij Sharma Copyright © 2008 Jack Gibson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. ISBN: 978-1-4357-3461-6 Book available at http://www.lulu.com/content/2872821 CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 To The Doon School 5 Bandarpunch-Gangotri-Badrinath 17 Gulmarg to the Kumbh Mela 39 Kulu and Lahul 49 Kathiawar and the South 65 War in Europe 81 Swat-Chitral-Gilgit 93 Wartime in India 101 Joining the R.I.N.V.R. 113 Afloat and Ashore 121 Kitchener College 133 Back to the Doon School 143 Nineteen-Fortyseven 153 Trekking 163 From School to Services Academy 175 Early Days at Clement Town 187 My Last Year at the J.S.W. 205 Back Again to the Doon School 223 Attempt on ‘Black Peak’ 239 vi An Indian Englishman To Mayo College 251 A Headmaster’s Year 265 Growth of Mayo College 273 The Baspa Valley 289 A Half-Century 299 A Crowded Programme 309 Chini 325 East and West 339 The Year of the Dragon 357 I Buy a Farm-House 367 Uncertainties 377 My Last Year at Mayo College 385 Appendix 409 PREFACE ohn Travers Mends (Jack) Gibson was born on March 3, 1908 and J died on October 23, 1994. -

Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule

TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A COMPILATION OF REFUGEE STATEMENTS 1958-1975 A SERIES OF “EXPERT ON TIBET” PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A Compilation of Refugee Statements 1958-1975 Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule is a collection of twenty-seven Tibetan refugee statements published by the Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1976. At that time Tibet was closed to the outside world and Chinese propaganda was mostly unchallenged in portraying Tibet as having abolished the former system of feudal serfdom and having achieved democratic reforms and socialist transformation as well as self-rule within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibetans were portrayed as happy with the results of their liberation by the Chinese Communist Party and satisfied with their lives under Chinese rule. The contrary accounts of the few Tibetan refugees who managed to escape at that time were generally dismissed as most likely exaggerated due to an assumed bias and their extreme contrast with the version of reality presented by the Chinese and their Tibetan spokespersons. The publication of these very credible Tibetan refugee statements challenged the Chinese version of reality within Tibet and began the shift in international opinion away from the claims of Chinese propaganda and toward the facts as revealed by Tibetan eyewitnesses. As such, the publication of this collection of refugee accounts was an important event in the history of Tibetan exile politics and the international perception of the Tibet issue. The following is a short synopsis of the accounts. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Mountaineering Books Under £10

Mountaineering Books Under £10 AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER EDITION CONDITION DESCRIPTION REFNo PRICE AA Publishing Focus On The Peak District AA Publishing 1997 First Edition 96pp, paperback, VG Includes walk and cycle rides. 49344 £3 Abell Ed My Father's Keep. A Journey Of Ed Abell 2013 First Edition 106pp, paperback, Fine copy The book is a story of hope for 67412 £9 Forgiveness Through The Himalaya. healing of our most complicated family relationships through understanding, compassion, and forgiveness, peace for ourselves despite our inability to save our loved ones from the ravages of addiction, and strength for the arduous yet enriching journey. Abraham Guide To Keswick & The Vale Of G.P. Abraham Ltd 20 page booklet 5890 £8 George D. Derwentwater Abraham Modern Mountaineering Methuen & Co 1948 3rd Edition 198pp, large bump to head of spine, Classic text from the rock climbing 5759 £6 George D. Revised slight slant to spine, Good in Good+ pioneer, covering the Alps, North dw. Wales and The Lake District. Abt Julius Allgau Landshaft Und Menschen Bergverlag Rudolf 1938 First Edition 143pp, inscription, text in German, VG- 10397 £4 Rother in G chipped dw. Aflalo F.G. Behind The Ranges. Parentheses Of Martin Secker 1911 First Edition 284pp, 14 illusts, original green cloth, Aflalo's wide variety of travel 10382 £8 Travel. boards are slightly soiled and marked, experiences. worn spot on spine, G+. Ahluwalia Major Higher Than Everest. Memoirs of a Vikas Publishing 1973 First Edition 188pp, Fair in Fair dw. Autobiography of one of the world's 5743 £9 H.P.S. Mountaineer House most famous mountaineers. -

The Changing Peasant: Part 2: the Uprooted

19791No. 41 by Richard Critchfield The Changing Peasant Asia [ RC-4-'793 Part II: The Uprooted Theirs is the true lost horizon. Whatever their number, most jutting rocks of shale, schist, and Tibetans are nomadic shepherds limestone. Tibet is the source of all The Tibetan homeland is still so who live in yak-hair tents and move the great rivers of Asia: the Sutlej remote, unmapped, unsurveyed, about much of the year in search of and Indus, the Ganges and and unexplored that in 1979 less is grass for their large herds of yaks, Brahmaputra, the Salween, known about its great Chang Tang sheep, goats, and horses. Aside Yangtze, and Mekong. Violent plateau and Himalayan-high from Lhasa (population 50,000) and gales, dust storms, and icy winds mountain ranges than is known some town-like monasteries, before blow almost every day. about the craters of the moon. the Chinese occupation almost no Until the Chinese occupation the human habitations existed; the Tibet remains a mystery. wheel, considered sacred, was Tibetan herdsman's life, like that of never used: horses, camels, yaks, the Arab Bedouin, revolves around sheep, and men provided the only It is now 29 years since Mao Tse- his livestock, their wool for clothing tung's armies invaded what had transport over rugged tracks and and shelter and their meat and milk precarious bridges spanning deep almost always been an independent for food. sovereign country and declared it an narrow gorges. Even the way of autonomous area within the The Tibetans are racially and death was harsh, the bodies being People's Republic of China. -

Lesson 1: Mount Everest Lesson Plan

Lesson 1: Mount Everest Lesson Plan Use the Mount Everest PowerPoint presentation in conjunction with this lesson. The PowerPoint presentation contains photographs and images and follows the sequence of the lesson. If required, this lesson can be taught in two stages; the first covering the geography of Mount Everest and the second covering the successful 1953 ascent of Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. Key questions Where is Mount Everest located? How high is Mount Everest? What is the landscape like? How do the features of the landscape change at higher altitude? What is the weather like? How does this change? What are conditions like for people climbing the mountain? Who were Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay? How did they reach the summit of Mount Everest? What did they experience during their ascent? What did they do when they reached the summit? Subject content areas Locational knowledge: Pupils develop contextual knowledge of the location of globally significant places. Place knowledge: Communicate geographical information in a variety of ways, including writing at length. Interpret a range of geographical information. Physical geography: Describe and understand key aspects of physical geography, including mountains. Human geography: Describe and understand key aspects of human geography, including land use. Geographical skills and fieldwork: Use atlases, globes and digital/computer mapping to locate countries and describe features studied. Downloads Everest (PPT) Mount Everest factsheet for teachers -

Current Affairs and Answer Sheet

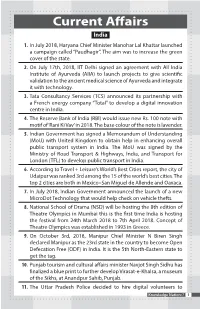

Current Affairs India 1. In July 2018, Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar launched a campaign called “Paudhagir”. The aim was to increase the green cover of the state. 2. On July 17th, 2018, IIT Delhi signed an agreement with All India Institute of Ayurveda (AIIA) to launch projects to give scientific validation to the ancient medical science of Ayurveda and integrate it with technology. 3. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) announced its partnership with a French energy company “Total” to develop a digital innovation centre in India. 4. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) would issue new Rs. 100 note with motif of ‘Rani Ki Vav’ in 2018. The base colour of the note is lavender. 5. Indian Government has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with United Kingdom to obtain help in enhancing overall public transport system in India. The MoU was signed by the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, India, and Transport for London (TFL) to develop public transport in India. 6. According to Travel + Leisure’s World’s Best Cities report, the city of Udaipur was ranked 3rd among the 15 of the world’s best cities. The top 2 cities are both in Mexico–San Miguel de Allende and Oaxaca. 7. In July 2018, Indian Government announced the launch of a new MicroDot Technology that would help check on vehicle thefts. 8. National School of Drama (NSD) will be hosting the 8th edition of Theatre Olympics in Mumbai this is the first time India is hosting the festival from 24th March 2018 to 7th April 2018. -

Scholar Mountaineers, by Wilfrid Noyce. 164 Pages, with 12 Full- Page Illustrations and Wood-Engravings by R

Scholar Mountaineers, by Wilfrid Noyce. 164 pages, with 12 full- page illustrations and wood-engravings by R. Taylor. London: Dennis Dobson, 1950. Price, 12/6. What does the title Scholar Mountaineers lead one to expect? Maybe a series of essays about dons who have climbed, or an account of the climbers who have written scholarly works on the history and litera ture of mountaineering. Instead of either of these, Wilfrid Noyce has given us, under this title, a dozen brief, informal studies of figures whom he describes as “Pioneers of Parnassus”: Dante, Petrarch, Rousseau, De Saussure, Goethe, William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Keats, Ruskin, Leslie Stephen, Nietzsche, Pope Pius XI and Captain Scott. Each of them is studied “simply in relation to mountains”; each is considered as having made “a peculiar con tribution to a certain feeling in us.” Such is the author’s interest in them (and, of course, in mountains) that a reader is soon prepared to suppress the little question that nags at first: How many were “scholars,” and how many were “mountaineers”? Reading on, one becomes more and more interested in these selective treatments of the “Pioneers,” and in the differentiation of attitudes which they expressed or—in most cases quite unintention ally—fostered. Dante appears, for example, as “the trembling and unwieldy novice” who “comes near to wrecking the whole expedi tion through Hell”; and Keats is detected in a moment of what seems to be bravado—composing a sonnet on the summit of Ben Nevis. The discrimination of various attitudes toward -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit .................................................................................................................................................. -

Static GK Capsule 2017

AC Static GK Capsule 2017 Hello Dear AC Aspirants, Here we are providing best AC Static GK Capsule2017 keeping in mind of upcoming Competitive exams which cover General Awareness section . PLS find out the links of AffairsCloud Exam Capsule and also study the AC monthly capsules + pocket capsules which cover almost all questions of GA section. All the best for upcoming Exams with regards from AC Team. AC Static GK Capsule Static GK Capsule Contents SUPERLATIVES (WORLD & INDIA) ...................................................................................................................... 2 FIRST EVER(WORLD & INDIA) .............................................................................................................................. 5 WORLD GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................................................ 9 INDIA GEOGRAPHY.................................................................................................................................................. 14 INDIAN POLITY ......................................................................................................................................................... 32 INDIAN CULTURE ..................................................................................................................................................... 36 SPORTS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Year 6 English CVPS Home Learning WC 22.06.20

Year 6 English CVPS Home Learning WC 22.06.20. Click on the lesson Lesson 1 you would like to complete today Lesson 2 Lesson 3 Lesson 4 Lesson 5 This week, you will be linking all of your English learning with your Discovery topic all about Mount Everest.. Monday- Diary entry Climbing Mount Everest: the first successful ascent Portrait of Edmund Hillary © RGS-IBG S0001324 Tenzing Norgay © RGS-IBG S0004902 Climbing Mount Everest • The first successful ascent Show pupils photographs of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. • Edmund Hillary was born on July 20, 1919, in Auckland, New Zealand. He had tried to climb Mount Everest previously in 1951. Tenzing Norgay was born in Tibet in 1914, in village within view of Mount Everest. • It is believed that when Norgay was a baby a holy man said that he was destined for great things and that this was when he was given the name Norgay, meaning ‘fortunate one’. Like Hillary, Tenzing Norgay had a spirit of adventure. • He built a reputation as a dependable, hardworking and knowledgeable porter and joined seven Everest expeditions prior to 1953. He said, ‘the pull of Everest was stronger for me than any force on Earth’. • In 1953 a British team, lead by army officer Colonel John Hunt attempted to climb Mount Everest. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were members of the 400 strong team. The equipment How do you think they What do you carried it all? think you would need to take to survive Everest? Baggage arrives at Tankot © RGS-IBG S0001271 • The equipment, which weighed 8333kg (7.5 tons), was carried all the way by 350 porters.