In Memoriam 2010, However Most of the Books Shortlisted Have Been Reviewed in Either This Volume Or 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

Charles Pickles (Presidenl 1976-1978) the FELL and ROCK JOURNAL

Charles Pickles (Presidenl 1976-1978) THE FELL AND ROCK JOURNAL Edited by TERRY SULLIVAN No. 66 VOLUME XXIII (No. I) Published by THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT 1978 CONTENTS PAGE Cat Among the Pigeons ... ... ... Ivan Waller 1 The Attempt on Latok II ... ... ... Pal Fearneough 1 The Engadine Marathon ... ... ... Gordon Dyke 12 Woubits - A Case History ... ... ... Ian Roper 19 More Shambles in the Alps Bob Allen 23 Annual Dinner Meet, 1976 Bill Comstive 28 Annual Dinner Meet, 1977 ... ... Maureen Linton 29 The London Section ... ... ... Margaret Darvall 31 High Level Walking in the Pennine Alps John Waddams 32 New Climbs and Notes ... ... ... Ed Grindley 44 In Memoriam... ... ... ... ... ... ... 60 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 76 Reviews ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 82 Officers of the Club 117 Meets 119 © FELL AND ROCK CLIMBINO CLUB PRINTED BY HILL & TYLER LTD., NOTTINGHAM Editor T. SULLIVAN B BLOCK UNIVERSITY PARK NOTTINGHAM Librarian IReviews MRS. J. FARRINGTON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BAILRIGG LANCASTER New Climbs D. MILLER 31 BOSBURN DRIVE MELLOR BROOK BLACKBURN LANCASHIRE Obituary Notices R. BROTHERTON SILVER BIRCH FELL LANE PENRITH CUMBRIA Exchange Journals Please send these to the Librarian GAT AMONG THE PIGEONS Ivan Waller Memory is a strange thing. I once re-visited the Dolomites where I had climbed as a young man and thought I could remember in fair detail everywhere I had been. To my surprise I found all that remained in my mind were a few of the spect• acular peaks, and huge areas in between, I might never have seen before. I have no doubt my memory of events behaves in just the same way, and imagination tries to fill the gaps. -

Pinnacle Club Journal

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL No. 19 1982 - 84 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL 1982 - 84 Edited by Kate Webb © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB Founded 1921 OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE - 1984 President SHEILA CORMACK 12 Greenfield Crescent, Balerno, Midlothian. EH 14 7HD (031 449 4663) Vice President Angela Soper Hon. Secretary Jay Turner 57 Fitzroy Road, London. NW1 8TS (01 722 9806) Hon. Treasurer Stella Adams Hon. Meets Secretary Fiona Longstaff Hon. Hut Secretary Lynda Dean Hon. Editor Kate Webb Back Garth, The Butts, Alston, Cumbria. CA9 3JU (0498 81931) Committee Avis Reynolds Wendy Aldred Dorothy Wright Suzanne Gibson Felicity Andrew Jean Drummond (Dinner Organiser) Hon. Auditor Hon. Librarian Ann Wheatcroft Margaret Clennett © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved Contents Cwm Dyli Shirley Angell ......... 5 No Weather for Picnics Margaret Clennett ..... 8 An Teallach at Last Belinda Swift.......... 11 California Sheila Cormack ........ 13 A Winter's Tail Anne McMillan........ 16 No Other Guide Angela Soper .......... 18 Trekking in Nepal Alison Higham ........ 21 Canoeing in Southern Ireland Chris Watkins ......... 22 Fool's Paradise Alex White............ 26 Off-Day Arizona Style Gwen Moffat.......... 27 International Women's Meet Angela Soper .......... 32 Rendez-vous Haute Montagne Pamela Holt........... 34 Day Out on Pillar Shirley Angell ......... 35 In Pursuit of Pleasure Gill Fuller ............ 38 Pindus Adventure Dorothy Wright ....... 41 Shining Cleft Janet Davies .......... 43 Climbing the Snowdon Horseshoe Royanne Wilding ...... 46 Births, Marriages and Deaths ........... 48 Members' Activities ........... 49 Obituaries ........... 51 Reviews ........... 54 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved President 1984: Sheila Cormack Photo: LyndaDean © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved CWM DYLI Shirley Angell On Sunday, March 27th, 1932, it poured with rain. -

Artur Hajzer, 1962–2013

AAC Publications Artur Hajzer, 1962–2013 Artur Hajzer, one of Poland’s best high-altitude climbers from the “golden age,” was killed while retreating from Gasherbrum I on July 7, 2013. He was 51. Born on June 28, 1962, in the Silesia region of Poland, Artur graduated from the University of Katowice with a degree in cultural studies. His interests in music, history, and art remained important throughout his life. He started climbing as a boy and soon progressed to increasingly difficult routes in the Tatras and the Alps, in both summer and winter, in preparation for his real calling: Himalayan climbing. He joined the Katowice Mountain Club, along with the likes of Jerzy Kukuczka, Krzysztof Wielicki, Ryszard Pawlowski, and Janusz Majer. His Himalayan adventures began at the age of 20, with expeditions to the Rolwaling Himal, to the Hindu Kush, and to the south face of Lhotse. Although the Lhotse expedition was unsuccessful, it was the beginning of his climbing partnership with Jerzy Kukuczka. Together they did the first winter ascent of Annapurna in 1987, a new route up the northeast face of Manaslu, and a new route on the east ridge of Shishapangma. Artur climbed seven 8,000-meter peaks and attempted the south face of Lhotse three times, reaching 8,300 meters on the formidable face. He even concocted a plan to climb all 14 8,000-meter peaks in one year, a scheme that was foiled by Pakistani officials when they refused him the required permits. Artur proved he was more than a climber when he organized the massively complicated “thunderbolt” rescue operation on Everest’s West Ridge, a disaster in which five members of a 10-member Polish team were killed. -

The Ultimate Rocky Road Trip

3/23/2021 The ultimate Rocky road trip The ultimate Rocky road trip Photos: Alamy, Parks Canada/Ryan Bray You could drive the Icefields Parkway in three hours. But you won’t. Whether you’re a walker, photographer or expert picnicker, this is the longest three-hour trip in the world. By Leslie Woit, Saturday 27 February, 2016 “There are two ways to see the Icefields Parkway (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/northamerica/canada/7366 34/A-seriously-good-spin.html). The hard way,” explained Banff mountain guide Chic Scott. “And the easy way.” In 1967, Chic was among a small team who completed the first high-level ski traverse from Jasper to Lake Louise. It took 21 days to negotiate that particular uncharted strip of Alberta’s Rocky Mountains (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/north- america/galleries/Rocky-Mountains-highlights-17-incredible-photographs- of-the-Rockies/), 300km over what he described as “a logical line along the s.telegraph.co.uk/graphics/projects/canada-travel-icefield-parkway/index.html 1/14 3/23/2021 The ultimate Rocky road trip Continental Divide”. They climbed peaks, hopscotched crevasse-riddled glaciers, crossed massive avalanche paths, all while passing through some of the most resplendent, rugged mountain scenery on Earth. The Canadian Rockies, Banff National Park. Banff Lake Louise Tourism/Paul Zizka And then there’s the easy way Parallel to Chic’s backcountry route, the Icefields Parkway cuts a swath through western Alberta from Jasper to Lake Louise, a civilised 230km highway paved smooth as a baby’s bottom. -

The Eiger Myth Compiled by Marco Bomio

The Eiger Myth Compiled by Marco Bomio Compiled by Marco Bomio, 3818 Grindelwald 1 The Myth «If the wall can be done, then we will do it – or stay there!” This assertion by Edi Rainer and Willy Angerer proved tragically true for them both – they stayed there. The first attempt on the Eiger North Face in 1936 went down in history as the most infamous drama surrounding the North Face and those who tried to conquer it. Together with their German companions Andreas Hinterstoisser and Toni Kurz, the two Austrians perished in this wall notorious for its rockfalls and suddenly deteriorating weather. The gruesome image of Toni Kurz dangling in the rope went around the world. Two years later, Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek managed the first ascent of the 1800-metre-high face. 70 years later, local professional mountaineer Ueli Steck set a new record by climbing it in 2 hours and 47 minutes. 1.1 How the Eiger Myth was made In the public perception, its exposed north wall made the Eiger the embodiment of a perilous, difficult and unpredictable mountain. The persistence with which this image has been burnt into the collective memory is surprising yet explainable. The myth surrounding the Eiger North Face has its initial roots in the 1930s, a decade in which nine alpinists were killed in various attempts leading up to the successful first ascent in July 1938. From 1935 onwards, the climbing elite regarded the North Face as “the last problem in the Western Alps”. This fact alone drew the best climbers – mainly Germans, Austrians and Italians at the time – like a magnet to the Eiger. -

Mountaineering Books Under £10

Mountaineering Books Under £10 AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER EDITION CONDITION DESCRIPTION REFNo PRICE AA Publishing Focus On The Peak District AA Publishing 1997 First Edition 96pp, paperback, VG Includes walk and cycle rides. 49344 £3 Abell Ed My Father's Keep. A Journey Of Ed Abell 2013 First Edition 106pp, paperback, Fine copy The book is a story of hope for 67412 £9 Forgiveness Through The Himalaya. healing of our most complicated family relationships through understanding, compassion, and forgiveness, peace for ourselves despite our inability to save our loved ones from the ravages of addiction, and strength for the arduous yet enriching journey. Abraham Guide To Keswick & The Vale Of G.P. Abraham Ltd 20 page booklet 5890 £8 George D. Derwentwater Abraham Modern Mountaineering Methuen & Co 1948 3rd Edition 198pp, large bump to head of spine, Classic text from the rock climbing 5759 £6 George D. Revised slight slant to spine, Good in Good+ pioneer, covering the Alps, North dw. Wales and The Lake District. Abt Julius Allgau Landshaft Und Menschen Bergverlag Rudolf 1938 First Edition 143pp, inscription, text in German, VG- 10397 £4 Rother in G chipped dw. Aflalo F.G. Behind The Ranges. Parentheses Of Martin Secker 1911 First Edition 284pp, 14 illusts, original green cloth, Aflalo's wide variety of travel 10382 £8 Travel. boards are slightly soiled and marked, experiences. worn spot on spine, G+. Ahluwalia Major Higher Than Everest. Memoirs of a Vikas Publishing 1973 First Edition 188pp, Fair in Fair dw. Autobiography of one of the world's 5743 £9 H.P.S. Mountaineer House most famous mountaineers. -

THE FUHRERBUCH of JOHANN JAUN by D

• .. THE FUHRERBUCH OF JOI-IANN JAUN . • • THE FUHRERBUCH OF JOHANN JAUN By D. F. 0. DANGAR ' WING to 1-Ians' abnormal carelessness in regard to all matters appertaining to himself, the greater part of his mountaineering achievements are not recorded in this book at all. He is fortunately in the habit of leaving it at home, or it would long since have been destroyed or lost.' Thus \vrote Sir Edward Davidson in the Fuhrerbuch of Hans Jaun, in 1887. Covering a period of thirty-five years, the book contains but thirty one entries most of them signed by the best known amateurs of the time and it is therefore a very incomplete history of J aun's career. Although his habit of leaving his book at home is, no doubt, the chief reason for the many omissions, several of his Herren must bear a share of the responsibility. J. Oakley Maund, for instance, apart from signing with C. T. Dent an entry in reference to an ascent of the Bietschhorn, has written less than a dozen lines in the book, and he does not specifically mention a single one of the many expeditions he made with Jaun. Of two entries by Herr Georg Griiber, one covers a period of seven years, and neither Maund nor Middlemore makes mention of the work of that glorious week in 1876 which, as one of the participants held, ' was entitled to be considered from a purely climbing point of view as a tour de force unsurpassed in the history of the Alps.' Middlemore, however, has paid a." well deserved tribute to his old guide in Pioneers of the Alps. -

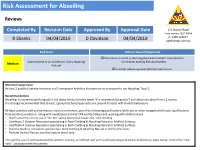

Risk Assessment for Abseiling

Risk Assessment for Abseiling Reviews Completed By Revision Date Approved By Approval Date 171 Nojoor Road Twin waters QLD 4564 P: 1300 122677 R Shanks 04/04/2019 D Davidson 04/04/2019 Apexcamps.com.au Risk level Action required/approval Document controls in planning documents and/or complete this Some chance or an incident or injury requiring Curriculum Activity Risk Assessment. Medium first aid Consider obtaining parental/carer permission. Minimum supervision At least 1 qualified Activity Instructor and 1 competent Activities Assistant are to be present to run Abseiling. Total 2. Recommendations Abseiling is recommended for grade 5 and above for the 6 metre tower. It is recommended grades 7 and above can abseil from 12 metres . It is strongly recommended that at least 1 group teachers/supervisors are present to assist with student behaviours All Apex activities staff and contractors hold at a minimum ,one of the following qualifications /skills sets or other recognised skill sets/ qualifications from another jurisdiction, along with mandatory First Aid/ CPR and QLD Blue Card, working with children check. • Staff trained for correct use of “Gri Gri” safety device that lowers the rock climbing . • Certificate 3 Outdoor Recreation specialising in Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Certificate 4 Outdoor Recreation specialising in Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Diploma Outdoor recreation specialising is Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Perform Vertical Rescue also Haul system abseil only. Through the use of well maintained equipment, training, accredited staff and sound operating procedures and policies, Apex Camps control the “real risks” associated with this activity In assessing the level of risk, considerations such as the likelihood of an incident happening in combination with the seriousness of a consequence are used to gauge the overall risk level for an activity. -

Gross Fiescherhorn 4048 M

Welcome to the Swiss Mountaineering School grindelwaldSPORTS. Gross Fiescherhorn 4048 m The programme: Day 1 Ascent to the Mönchsjoch hut 3650m After riding the train up to the Jungfraujoch, you will head to the Aletsch exit. Follow the marked foot- path and you walk comfortably to the ‘Mönchsjochhütte’. Take your time for these first couple of me- ters in high altitude in order to acclimatize yourself optimally. Shortly before dinner, you will meet your guide in the Mönchsjoch hut. Day 2 Summit tour to Fiescherhorn 4048m Early in the morning we hike across the ‘Ewig Schneefeld’ until we reach the same name ridge below Walcherhorn; the first bit in the light of our headlamps. Over the impressive ridge we climb higher and higher to the summit slope. A little steeper, now and then over bare ice, we reach the Firngrat, which leads us shortly to the summit. The view over the huge Fiescherhorn north face is unique. In front of us arise steeply the Eiger and the Schreckhorn, in the background we have a fantastic view over the the Swiss Mittelland. We take the same route back on our descent, which guides us back to the Jung- fraujoch. What you need to know… Meeting point: 5.30 pm Mönchjochhut Your journey: If arriving by car, we recommend to park at the train station in Grindelwald Grund. Purchase a return ticket to the Jungfraujoch. If arriving by train, you can buy your train ticket at any train station. Requirements: Day 1 Day 2 200 elevation gain 1050 elevation gain 0 elevation loss 1230 elevation loss 1.8 kilometres 12.5 kilometres Walking time: around 1 hour Walking time: around 6-7 hours Technical difficulty: medium Equipment: See equipment list in the appendix. -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

Improving Rock Climbing Safety Using a Systems Engineering Approach

Lyle Halliday u5366214 Improving Rock Climbing Safety using a Systems Engineering Approach ENGN2225- Systems Engineering and Design, Portfolio Abstract This portfolio outlines an application of Systems Engineering methods to the sport of Rock climbing. The report outlines an organized, logical analysis of the system that is involved in making this sport safe and aims to improve the system as a whole through this analysis. Steps taken include system scoping, requirements engineering, system function definition, subsystem integration and system attributes which contribute toward a final concept. Two recommendations are made, one being a bouldering mat which incorporates the transportation of other equipment, the other being complete, standardised bolting protocols. These concepts are then verified against the design criteria and evaluated. 1.0 System scoping: A systematic way of establishing the boundaries of the project and focusing the design problem to an attainable goal. The project focuses on Lead Climbing. 2.0 Requirements engineering: Establishing the true requirements of climbers, and what they search for in a climbing safety system 2.1 Pairwise Analysis: Establishing safety, ease of use and durability as primary design goals 2.2 Design Requirements and Technical Performance Measures: Specifying the design requirements into attainable engineering parameters. 2.3 House of Quality: Identifying the trade-offs between safety and functionality/ cost and the need for a whole-of-systems approach to the problem, rather than a component approach. 3.0 System Function Definition: Establishing concepts and system processes. 3.1 Concept Generation and Classification: Identifying possible and existing solutions on a component level and taking these to a subsystem level.