Emasters Title Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences and the Community at Large

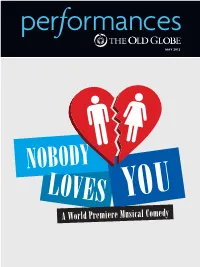

may 2012 NOBODY LOVES YOU A World Premiere Musical Comedy Welcome to The Old Globe began its journey with Itamar Moses and Gaby Alter’s Nobody Loves You in 2010, and we are thrilled to officially launch the piece here in its world premiere production. The Globe has a longstanding relationship with Itamar Moses. He was a Globe Playwright-in-Residence in 2007-2008 when we produced the world premieres of his plays Back Back Back and The Four of Us. Nobody Loves You is filled with the same HENRY DIROCCO HENRY whip-smart humor and insight that mark Itamar’s other works, here united with Gaby’s vibrant music and lyrics. Together they have created a piece that portrays, with a tremendous amount of humor and heart, the quest for love in a world in which romance is often commercialized. Just across Copley Plaza, the Globe is presenting another musical, the acclaimed The Scottsboro Boys, by musical theatre legends John Kander and Fred Ebb. We hope to see you back this summer for our 2012 Summer Shakespeare Festival. Under Shakespeare Festival Artistic Director Adrian Noble, this outdoor favorite features Richard III, As You Like It and Inherit the Wind in the Lowell Davies Festival Theatre. The summer season will also feature Michael Kramer’s Divine Rivalry as well as Yasmina Reza’s Tony Award-winning comedy God of Carnage. As always, we thank you for your support as we continue our mission to bring San Diego audiences the very best theatre, both classical and contemporary. Michael G. Murphy Managing Director Mission Statement The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: Creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; Producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; Ensuring diversity and balance in programming; Providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences and the community at large. -

Wednesday Morning, Jan. 27

WEDNESDAY MORNING, JAN. 27 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) 47008 AM Northwest Be a Millionaire The View Journalist E.D. Hill. (N) Live With Regis and Kelly (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) 626517 (cc) 17282 21973 (cc) (TV14) 59843 (TVG) 46379 KOIN Local 6 News 33331 The Early Show (N) (cc) 69244 Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right Contestants bid The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 Early at 6 80824 66244 for prizes. (N) (TVG) 88379 (TV14) 91843 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Gayle Haggard; Sharon Osbourne. (N) (cc) 867060 Rachael Ray (cc) (TVG) 86911 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 44534 Lilias! (cc) (TVG) Between the Lions Curious George Sid the Science Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Tribute to Number Clifford the Big Dragon Tales WordWorld (TVY) Martha Speaks 10/KOPB 10 10 19350 (TVY) 89517 (TVY) 25824 Kid (TVY) 43701 (TVY) 27718 (TVY) 26089 Seven. (N) (cc) (TVY) 35398 Red Dog 91379 (TVY) 39553 11060 (TVY) 29089 Good Day Oregon-6 (N) 71602 Good Day Oregon (N) 16176 The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 20466 Paid 86447 Paid 24621 The Martha Stewart Show (N) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (TVG) 15447 Paid 86486 Paid 17008 Paid 49195 Paid 28602 Through the Bible Life Today 15553 Christians & Jews Paid 34176 Paid 91060 Paid 67319 Paid 78244 Paid 79973 22/KPXG 5 5 16282 67355 Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- The Word in the Inspirations Lifestyle Maga- Behind the Alternative James Robison Marilyn -

He's Got the Flavor and the Fav(Or)

small fleet business [ PROFILE He’s Got the Flavor and ] the Fav(or) “Big Rick” heads up a Las Vegas limousine company that has served celebrities, weekend partygoers, and a rapper star from a hit reality VH1 series By Conor Izzett hen your nickname is ance as driver and sidekick to rapper Big Rick, you tend to Flavor Flav on VH1’s hit reality show, get noticed. But Rick B. “Flavor of Love.” Opportunity fi rst Head, standing 6 feet, 9 knocked when the production compa- Winches tall, never expected the kind of ny working for VH1 was looking for a attention he gets now. His wife, Ursula driver for Flav’s original show, “Strange Head, explains. Love,” co-starring former supermodel “We were staying at the Four Sea- Brigitte Nielsen. ■ Big Rick got lots of attention for sons, and these ladies had all their “They wanted a driver who knew his role as chauffeur sidekick to rap- bags, and they all dropped them and Vegas, someone who was not camera per Flavor Fav on VH1. His experi- ence working with celebrities and said, ‘Oh my god, are you Big Rick?’ shy, and was comfortable around ce- partygoers led to steady corporate And he said yes. So then these ladies lebrities,” Big Rick says. “They needed work. start digging though their luggage right someone to do their job and not be in- there in front of the hotel, looking for timidated by the camera. I said, ‘What ‘you’re‘you’re one bigbig mother—’ And the rest their cameras. It was just funny.” camera?’” is history.” Big Rick, owner of Head Limo in Las After that, the audition was simple. -

Chilli Dating Anyone in ? the 'Girls Cruise' Star Is Opening up About Heartbreak Navigation Menu

Jul 22, · Chilli's journey towards finding love in the public eye has been well-documented from a high-profile relationship with Usher to What Chilli Wants, her former reality show about her quest to Author: Tai Gooden. Aug 20, · Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas, 47, wants Black women to shake up their dating habits and explore what it’s like to go out with men outside of their race.. One-third of the iconic girl group TLC. Is Chilli Dating Anyone In ? The 'Girls Cruise' Star Is Opening Up About Heartbreak Navigation menu. In, Thomas and Watkins performed a series of concerts in Asia. In, Thomas lost her dating and was ordered by doctors right to sing. Thomas began working on her chilli album in after the completion of dating for TLC's third album, FanMail. Jan 30, · Chilli, meanwhile, hasn't exactly had it easy in her dating life. Back in , she had a very high- profile relationship with the R&B singer Usher, which ended when she realized that he was. Rozonda Ocielian Thomas born February 27,, dated professionally as Chilli, is an American singer-songwriter, tionne, actress, television personality and model who rose to fame in the early s as a dating of group TLC, one of the best-selling girl groups of the 20th dating. Rozonda 'Chilli' Thomas is dated to have hooked up with Wayne Brady in. Aug 20, · Rozonda "Chilli" Thomas has some advice for Black woman looking for that Prince Charming,. She wants them to date "primarily" White men. Chilli spoke with Essence to promote the eight-part Netflix music documentary series Once In A Lifetime Sessions which features TLC. -

Newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 212 - September 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/07 (Nr. 212) September 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, schen und japanischen DVDs Aus- Nach den in diesem Jahr bereits liebe Filmfreunde! schau halten, dann dürfen Sie sich absolvierten Filmfestivals Es gibt Tage, da wünscht man sich, schon auf die Ausgaben 213 und ”Widescreen Weekend” (Bradford), mit mindestens fünf Armen und 214 freuen. Diese werden wir so ”Bollywood and Beyond” (Stutt- mehr als nur zwei Hirnhälften ge- bald wie möglich publizieren. Lei- gart) und ”Fantasy Filmfest” (Stutt- boren zu sein. Denn das würde die der erfordert das Einpflegen neuer gart) steht am ersten Oktober- tägliche Arbeit sicherlich wesent- Titel in unsere Datenbank gerade wochenende das vierte Highlight lich einfacher machen. Als enthu- bei deutschen DVDs sehr viel mehr am Festivalhimmel an. Nunmehr siastischer Filmfanatiker vermutet Zeit als bei Übersee-Releases. Und bereits zum dritten Mal lädt die man natürlich schon lange, dass Sie können sich kaum vorstellen, Schauburg in Karlsruhe zum irgendwo auf der Welt in einem was sich seit Beginn unserer Som- ”Todd-AO Filmfestival” in die ba- kleinen, total unauffälligen Labor merpause alles angesammelt hat! dische Hauptstadt ein. Das diesjäh- inmitten einer Wüstenlandschaft Man merkt deutlich, dass wir uns rige Programm wurde gerade eben bereits mit genmanipulierten Men- bereits auf das Herbst- und Winter- offiziell verkündet und das wollen schen experimentiert wird, die ge- geschäft zubewegen. -

Rapper-Repped Clothing Co. Hits Under Armour with TM Suit - Law360 Page 1 of 2

Rapper-Repped Clothing Co. Hits Under Armour With TM Suit - Law360 Page 1 of 2 Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Rapper-Repped Clothing Co. Hits Under Armour With TM Suit By Aaron Vehling Law360, New York (March 06, 2015, 2:07 PM ET) -- Hydro Clothing, an apparel brand featured on several VH1 reality shows featuring former Public Enemy rapper Flavor Flav, on Thursday sued Under Armour Inc. in a California federal court, alleging that Under Armour’s similarly named products infringe on Hydro’s trademarks. Hydro Clothing, a name under which Cohen International Inc., does business, says in its suit that Under Armour’s line of shirts, board shorts, pants, hoodies and other apparel under the name “Hydro” and “Hydro Armour” is deceptive and likely to confuse consumers. The complaint also names Dick’s Sporting Goods Inc., which sells Under Armour’s clothing line. “[Under Armour]’s unauthorized use of the Hydro mark is a trademark use which is likely to confuse the reasonably prudent consumer into believing that [Under Armour]’s infringing apparel products are produced by Cohen,” the complaint says. “On information and belief, Dick’s and [other] retailers are continuing to sell [Under Armour] products bearing the Hydro mark, despite being requested in writing by Cohen to cease their infringement of the Hydro mark.” Before filing the lawsuit, Hydro Clothing also sent Under Armour directly a cease-and- desist notice, but the apparel company continues to promote and sell products under the Hydro mark, the complaint says. -

Hy-Vee MEAT DEPARTMENT Means

FRIDAY ** AFTERNOON ** FEBRUARY 27 THURSDAY ** AFTERNOON ** MARCH 5 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Assignment: The Reading Rainbow Arthur ‘‘My Music WordGirl Dr. Two The Electric Cyberchase Wishbone ‘‘Bark to Nightly Business KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Design Squad ‘‘No Reading Rainbow Arthur ‘‘Fern’s WordGirl Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase ‘‘True Wishbone ‘‘The Nightly Business Street (S) (EI) Neighborhood Bears (S) (S) (EI) World ‘‘Show Way’’ Rules.’’ (S) (EI) Brains threatens. Company (S) (EI) ‘‘Crystal Clear’’ the Future’’ (S) Report (N) (S) Street (S) (EI) Neighborhood (S) Bears (S) Chasing a pickle. Crying in Baseball’’ ‘‘Best Friends.’’ Slumber Party.’’ WordGirl’s identity. Ruffman (S) (EI) Colors’’ (S) (EI) Count’s Account’’ Report (N) (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) The Tyra Banks Show Rosie O’Donnell; Little House on the Prairie ‘‘No Beast Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show Actor News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News KTIV f X News (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) The Tyra Banks Show (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘A Promise Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show ‘‘The News NBC Nightly News Ruby Dee. (N) (S) So Fierce’’ David Arquette. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Ballgame Local teams go head to head in CAPE CORAL Bud Roth tourney DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Mostly Sunny • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Saturday: Partly Cloudy — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 89 Friday, April 17, 2009 50 cents Cape man guilty on all counts in ’05 shooting death “I’m very pleased with the verdict. This is a tough case. Jurors deliberate for nearly 4 hours It was very emotional for the jurors, but I think it was the right decision given the evidence and the facts of the By CONNOR HOLMES tery with a deadly weapon. in the arm by co-defendant Anibal case.” [email protected] Gaphoor has been convicted as Morales; Jose Reyes-Garcia, who Dave Gaphoor embraced his a principle in the 2005 shooting was shot in the arm by Morales; — Assistant State Attorney Andrew Marcus mother, removed his coat and let death of Jose Gomez, 25, which and Salatiel Vasquez, who was the bailiff take his fingerprints after occurred during an armed robbery beaten with a tire iron. At the tail end of a three-day made the right decision. a 12-person Lee County jury found in which Gaphoor took part. The jury returned from approxi- trial and years of preparation by “I’m very pleased with the ver- him guilty Thursday of first-degree Several others were injured, mately three hours and 45 minutes state and defense attorneys, dict,” he said Thursday. “This is a felony murder, two counts of including Rigoberto Vasquez, who of deliberations at 8 p.m. -

“It's Gonna Be Some Drama!”: a Content Analytical Study Of

“IT’S GONNA BE SOME DRAMA!”: A CONTENT ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYALS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ON BET’S COLLEGE HILL _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by SIOBHAN E. SMITH Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2010 © Copyright by Siobhan E. Smith 2010 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “IT’S GONNA BE SOME DRAMA!”: A CONTENT ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYALS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ON BET’S COLLEGE HILL presented by Siobhan E. Smith, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz Professor Melissa Click Professor Ibitola Pearce Professor Michael J. Porter This work is dedicated to my unborn children, to my niece, Brooke Elizabeth, and to the young ones who will shape our future. First, all thanks and praise to God, from whom all blessings flow. For it was written: “I can do all things through Christ which strengthens me” (Philippians 4:13). My dissertation included! The months of all-nighters were possible were because You gave me strength; when I didn’t know what to write, You gave me the words. And when I wanted to scream, You gave me peace. Thank you for all of the people you have used to enrich my life, especially those I have forgotten to name here. -

Sunday Morning, Nov. 1

SUNDAY MORNING, NOV. 1 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (cc) 57642 NASCAR Countdown (Live) 19081 NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Amp Energy 500. (Live) 156028 2/KATU 2 2 85536 Paid 44791 Paid 46062 CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) (TVG) 77739 Face the Nation The NFL Today (Live) (cc) 60739 NFL Football Denver Broncos at Baltimore Ravens. (Live) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (TVG) 78062 766284 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Newschannel 8 at 7:00 (N) (cc) 60130 Meet the Press (N) (cc) 55807 Paid 55710 Paid 83994 Running New York City Marathon. 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 35212 (Same-day Tape) (TVPG) 18505 Betsy’s Kinder- Make Way for Mister Rogers Dinosaur Train Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Cloud: Challenge of the Silent Invasion: An Oregon Field 10/KOPB 10 10 garten 80517 Noddy 97710 20536 (TVY) 32371 29333 (TVY) 28604 Europe 42284 Edge 73642 Stallions. (TVPG) 38555 Guide Special (cc) (TVG) 18791 FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) 11888 Fox NFL Sunday (Live) (cc) (TVPG) NFL Football Seattle Seahawks at Dallas Cowboys. (Live) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) 74468 84333 395710 Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting Turning Point Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Paid 42826 Paid 57246 Paid 94888 Paid 31710 Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 22/KPXG 5 5 63994 29062 (TVG) 48197 (cc) (TVG) 927284 282623 Jentezen Franklin Dr. -

Issue 12 Working Copy

A Public Forum for News, Opinion, and Creative Thought of The Governor’s Academy MAY 20, 2009 VOLUME 50, ISSUE 11 Commencement Speaker Mabry: A Biography N H I S S S U E I T I : He gained public acclaim by Gabriella Riley ‘ 0 9 after the publishing of his memoir, White Bucks and Black- ED I TO R I A L S The 2009 Commencement Speaker, Marcus Mabry, is a Eyed Peas: Coming of Age Black Listen Up Seniors! 2 distinguished man indeed. A in White America. His latest Stanford grad, Mabry quickly book, a biography of rose up the journalism ladder Condoleezza Rice, is called to become the Chief of Twice As Good; Condoleezza Rice Correspondents and a senior and her Path to Power. T h i s editor for Newsweek, where book has been critically acclaimed, with one re v i e w www.yourspacecorner.com he oversaw the magazine’s domestic as well as interna- stating: “Marcus Mabry tional bureaus. Currently he is uncovers what has never been Perez and the Media 2 an editor at The New York shown before – what some Times. suspected didn’t exist – the P I N I O N O In 1996, Mabry won the personal Condoleezza Rice. A AP Exams 3 OPC’s Morton Frank Award tour de force!” for Best Business Reporting. “ M a rc Mabry epitomizes He also won the New York the great American success Association of Black s t o r y,” says Headmaster Journalists award for Personal Marty Doggett. “Coming from Commentary, the New York modest circumstances, he took Association of Black maximum advantage of his abilities, talents and opportu- http://ih.ca.campusgrid.net Journalists 2003 Tr a i l b l a z e r Marcus Mabry Aw a rd, and a Lincoln nities.