Prosthetic Culture: Photography, Memory and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quintet Blanquet / Masse / Shelton / Swarte / Ware

QUINTET BLANQUET / MASSE / SHELTON / SWARTE / WARE DOSSIER DE PRESSE 113.023.02 > 119.04.099.04.09 Vernissage Affi che de l’exposition QUINTET par Joost Swarte Jeudi 12 février 2009 à 19h en présence des artistes Horaires d’ouverture du mercredi au dimanche de 12h à 19h Contacts presse Muriel Jaby / Élise Vion-Delphin T (33) 04 72 69 17 05 / 25 [email protected] Images 300 dpi disponibles sur demande Musée d’art contemporain Cité internationale 81 quai Charles de Gaulle 69006 LYON Cedex 06 T (33) 04 72 69 17 17 F (33) 04 72 69 17 00 www.mac-lyon.com QUINTET BLANQUET / MASSE / SHELTON / SWARTE / WARE 113.023.02 > 119.04.099.04.09 L’EXPOSITION 3 STÉPHANE BLANQUET 4 MASSE 6 GILBERT SHELTON 8 JOOST SWARTE 10 CHRIS WARE 12 CATALOGUE 14 INFOS PRATIQUES 15 QUINTETL’EXPOSITION QUINTET En 1967, Bande dessinée et Figuration narrative, présentée Chris Ware, auteur prolifi que au découpage novateur auBLANQUET Musée des Arts décoratifs à Paris, inaugurait l’entrée de la et exacerbé, présentera pour la première fois en bande dessinée dans le Musée. Cette exposition consistait à France un ensemble de plus de 70 planches dessinées légitimer la bande dessinée à travers la Figuration Narrative, dans un foisonnement de cases vertigineuses. De ou était-ce plutôt valoriser la Figuration Narrative par la Jimmy Corrigan à Quimby the Mouse en passant bande dessinée ? En tout état de cause, l’ambiguité demeure. par Big Tex, Rocket Sam ou Rusty Brown ; ses héros évoluent dans un univers saturé de signes. -

La Clé Des Champs Urbains En Gironde

SPIL a c l é d e s c h a m pRIT s u r b a i n s e n G i r o n d e #30 Mai 2007 GRATUIT Mai #30 LA MATIÈRE ET L’ESPRIT La belle ou la bête Le prêtre Manes, au III° siècle, affirmait que le monde dépendait de deux puissances adverses : la Lumière contre les Ténèbres, le Bien contre le Mal. Et l’on se moque souvent de cette façon de penser simpliste et brutale où la réalité se limite à un échiquier à deux cases. Cases qui pourraient se décliner à l’infini suivant nos désirs et nos croyances : matière et esprit, Eros et Thanatos, Orient et Occident, inné et acquis, santé et maladie, 0 et1, etc. « Au moment de la résolution, les tonalités délicates s’épaississent, l’arc-en-ciel du réel et le grain subtil de nos vies s’effacent pour se réduire à deux pôles contraires. » Ces dualismes sont toujours décevants car ils délaissent la complexité et le chatoiement des êtres, leurs variétés singulières et leurs histoires personnelles. La sagesse populaire sait bien d’ailleurs que personne n’est tout bon ou tout méchant et que le charbon est une forme de diamant. Mais quand il faut choisir, quand la décision doit remplacer la finesse des délibérations, alors les positions se raidissent, le contraste augmente, il faut trancher. Au moment de la résolution, les tonalités délicates s’épaississent, l’arc-en-ciel du réel et le grain subtil de nos vies s’effacent pour se réduire à deux pôles contraires. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17393 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE MARDI 26 DÉCEMBRE 2000 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Il y a un an, les tempêtes b Fin décembre 1999, deux tempêtes exceptionnelles traversaient la France b Electricité : quelles leçons en a tirées EDF ? b Forêts : les dégâts restent immenses b Assurances : un particulier sur dix n’a pas encore été indemnisé IL Y A UN AN, les 26 et 27 décembre 1999, deux tempêtes exceptionnelles traversaient la France d’ouest en est, laissant des REUTERS traces encore visibles. La vitesse ÉLECTIONS LÉGISLATIVES du vent a été de 150 à 165 km/h, BBC/FRANCE 3 des rafales dépassant, parfois, 200 km/h. Selon les Eaux et Forêts, e Démocratie il faut remonter au XVII siècle ENQUÊTE SUR UN ENGOUEMENT pour enregistrer des dégâts compa- rables. Le Monde en dresse le bilan en Serbie matériel et économique. La forêt a Dinosaures : le nouveau règne payé le plus fort tribut : 138 mil- lions de mètres cubes de bois ont La page Milosevic été abattus, et le travail de plu- des terribles lézards sieurs générations de forestiers a est tournée été parfois mis à terre. 3,5 millions La coalition de partis qui avait porté Vojis- LE DINOSAURE, sous toutes ses de 19 millions de spectateurs en de foyers furent privés d’électrici- lav Kostunica (photo) à la présidence de formes, dans toutes les matières et Grande-Bretagne, 40 millions aux té, dont 12 % vivaient encore sans la Yougoslavie, l’Opposition démocra- pour tous les usages, atteint une Etats-Unis, et 6 millions en France. -

La Bande Dessinée, Nouvelle Frontière Artistique Et Culturelle

LA BANDE DESSINÉE, NOUVELLE FRONTIÈRE ARTISTIQUE ET CULTURELLE 54 propositions pour une politique nationale renouvelée Rapport au Ministre de la Culture Pierre Lungheretti Avec la collaboration de Laurence Cassegrain, directrice de projet à la DGMIC-Service du Livre et de la Lecture Janvier 2019 1 2 En hommage à Francis Groux et Jean Mardikian, pionniers de cette nouvelle frontière. « La bande dessinée est l’enfant bâtard de l’art et du commerce », Rodolphe Töpffer (1799-1846) "La bande dessinée en l’an 2000 ? Je pense, j’espère, qu’elle aura enfin acquis droit de cité, qu’elle se sera, si j’ose dire « adultifiée ». Qu’elle ne sera plus cette pelée, cette galeuse, d’où vient tout le mal, cette entreprise, dixit certains – d’abrutissement. Qu’elle sera devenue un moyen d’expression à part entière, comme la littérature ou le cinéma [auquel, soit dit en passant, elle fait pas mal d’emprunts]. Peut-être –sans doute –aura-t-elle trouvé, d’ici là, son Balzac. Un créateur qui, doué à la fois sur le plan graphique et sur le plan littéraire aura composé une véritable œuvre". Hergé 3 4 SYNTHÈSE 1. La bande dessinée française connaît depuis 25 ans une vitalité artistique portée par la diversification des formes et des genres. Art jeune apparu au XIX ème siècle, un peu avant le cinéma, la bande dessinée française connaît depuis près de vingt-cinq ans une phase de forte expansion, que certains observateurs qualifient de « nouvel âge d’or », dans un contexte mondial d’essor artistique du 9 ème art. -

Chapter 7 Jarry's Engagement with Contemporary Culture

RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN ‘UBUSING’ CULTURE Alfred Jarry’s Subversive Poetics in the Almanachs du Père Ubu Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Letteren aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 19 november 2009 om 14.45 uur door Marieke Dubbelboer geboren op 20 december 1977 te Emmen 2 Promotor: Prof. Dr. E.J.Korthals Altes Copromotor: Dr. E.C.S. Jongeneel Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. Dr. P. Besnier Prof. Dr. R. Grüttemeier Prof. Dr. H.L.M. Hermans ISBN: 978-90-367-4107-1 Table of contents Foreword .................................................................................................... 7 Introduction .............................................................................................. 9 Alfred Jarry (1873-1907) ....................................................................... 9 The Almanachs du Père Ubu ................................................................ 10 Aims of this study ............................................................................... 12 Approach and outline of the book ........................................................ 14 Chapter 1 Symbolism and Beyond. An Introduction to Jarry’s Life, Work and Poetics .............................................................................................. 16 1.1 Life and work ................................................................................... 16 1.1.1 Early years ................................................................................ -

Le Neuvième Art, Légitimations Et Dominations Jacques-Erick Piette

Le neuvième art, légitimations et dominations Jacques-Erick Piette To cite this version: Jacques-Erick Piette. Le neuvième art, légitimations et dominations. Sociologie. Université Sorbonne Paris Cité, 2016. Français. NNT : 2016USPCA081. tel-01541603 HAL Id: tel-01541603 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01541603 Submitted on 19 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris 3 – Sorbonne nouvelle Ecole doctorale 267 : Arts et médias CERLIS, UMR 8070 Sorbonne Nouvelle / Paris Descartes / CNRS / USPC Thèse de doctorat en Sociologie par Jacques-Erick Piette Le neuvième art, légitimations et dominations Sous la direction de Bruno Péquignot Soutenue le 13 septembre 2016 Jury : Serge Chaumier, professeur de sociologie, université d’Artois Eric Dacheux, professeur en information et communication, université Blaise Pascal – Clermont-Ferrand, rapporteur Jean-Louis Fabiani, Directeur d’Etudes en sociologie, EHESS, Paris, rapporteur François Mairesse, professeur d’information et communication, université Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris -

Quartier Jeunesse ATELIER

Jeudi 26 - 10h - Quartier Jeunesse Jeudi 26 - 14h30 - Hôtel du Palais - Place Louvel ATELIER : Le Journal de Mickey RENCONTRE : The origins of Raw Fausse couverture (sur réservation et en continu jusqu'à 19h) Retour sur une aventure graphique et artistique sans précédent avec Françoise Mouly, Charles Burns et Aline Kominski-Crumb. Jeudi 26 - 10h - Quartier Jeunesse ATELIER : Le Journal de Mickey Jeudi 26 - 15h - Conservatoire Badges personnalisés (sur réservation et en continu jusqu'à 19h) CONFÉRENCE : L'Univers Marvel a 50 ans par Jean-Marc Lainé Jeudi 26 - 10h - Quartier Jeunesse RENCONTRE JEUNESSE : avec Vincent Pianina Jeudi 26 - 15h - Quartier Jeunesse (10 petits insectes) RENCONTRE JEUNESSE : avec Nob (Les souvenirs de Mamette), avec Canal J Jeudi 26 - 11h - Espace Franquin, Salle Bunuel SPECTACLE : Emission Les affranchis d'Isabelle Giordano Jeudi 26 - 15h30 - Conservatoire - France Inter RENCONTRE : Lignes claires pour écrans noirs - Etat des lieux de la BD numérique Jeudi 26 - 11h - Pavillon Jeunes Talents® Panorama des approches artistiques des beaux livres, bd, graphic PRÉSENTATION DE BOOKS : aux éditions La Boîte à novel et clés pour penser l'ergonomie de la lecture de la bd en Bulles numérique et l'animationavec : Samuel Petit / ActiaLuna, Thomas Cadène / Les autres gens, Wandrille /éditions Warum Vraoum Jeudi 26 - 11h - Pavillon Jeunes Talents® PRÉSENTATION DE BOOKS : aux éditions Soleil Jeudi 26 - 16h - Quartier Jeunesse RENCONTRE JEUNESSE : avec Djet et Ludovic Danjou Jeudi 26 - 11h - Quartier Jeunesse (L'île de Puki), -

Small Panels for Lower Ranges. an Interdisciplinary Approach to Contemporary Portuguese Comics and Trauma

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN & FACULDADE DE LETRAS FACULTEIT LETTEREN Small panels for lower ranges. An Interdisciplinary approach to Contemporary Portuguese Comics and Trauma. Pedro David Vieira de Moura Advisors: Doctor Fernanda Gil Costa (Faculdade de Letras, UL) Doctor Jan Baetens (Faculteit Letteren, KUL) Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor no ramo de Estudos de Literatura e Cultura, na especialidade de Estudos Comparatistas 2017 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN & FACULDADE DE LETRAS FACULTEIT LETTEREN Small panels for lower ranges. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Contemporary Portuguese Comics and Trauma. Pedro David Vieira de Moura Advisors: Doctor Fernanda Gil Costa (Faculdade de Letras, UL) Doctor Jan Baetens (Faculteit Letteren, KUL) Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor no ramo de Estudos de Literatura e Cultura, na especialidade de Estudos Comparatistas Júri: Presidente: Doutora Maria Cristina de Castro Maia de Sousa Pimentel, Professora Catedrática e Membro do Conselho Científico da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, Vogais: Doctor Jan Baetens, Full Professor from Faculty of Arts of the Catholic University of Leuven; Doutora Maria Manuela Costa da Silva, Professora Auxiliar Convidada do Instituto de Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade do Minho; Doutora Susana Maria Simões Martins, Professora Auxiliar Convidada da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa; Doutora Helena Etelvina de Lemos Carvalhão Buescu, Professor Catedrática da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa; Doutora Luísa Susete Afonso Soares, Professora Auxiliar da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa. 2017 This dissertation was carried out while I was a recipient of a PhD scholarship from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. -

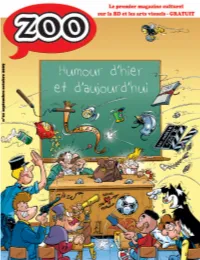

ZOO21 HQ Web.Pdf

N°21 sept-oct 2009 3 Éditorial ÿ Nous rions et nous rirons, car le sérieux a toujours été lÊami des imposteurs. Ÿ Hugo Foscolo (1778-1827), Accademia dei pitagorici a bande dessinée est née de lÊhumour. William Hogarth, lÊun Peut-être ceci peut-il expliquer en partie le manque de reconnaissan- des premiers artistes à illustrer des séquences narratives com- ce dont a souffert la bande dessinée, et la BD dÊhumour en particulier. L mentées, sÊexprime à travers la satire. Quelques années plus (Et ZOO nÊest pas non plus exempt de reproches à ce sujet.) tard, Töpffer puis Caran dÊAche mettent en images des railleries et Il était donc logique que nous consacrions un dossier à lÊhumour, cette posent ainsi les bases du neuvième art. Pour bien mesurer lÊimportan- discipline qui est la plus exigeante, la plus ingrate et en réalité la plus ce de ce genre, il suffit dÊanalyser un tant soit peu les grandes étapes noble de toutes. Parce que le sujet est aussi vaste que passionnant, de la bande dessinée : toutes, ou presque, sont provoquées par ce nous avons restreint notre réflexion en nous interrogeant sur les diffé- mode narratif. Si lÊon sÊattarde sur le cas de la censure des illustrés, on rences entre courants passés et présents. LÊoccasion nous est aussi constate que lÊhumour, lÊérotisme et le fantastique forment le trio de donnée de souhaiter un bon anniversaire à Fluide Glacial et de remer- tête des genres les plus réprimés. Mais seul lÊhumour a su faire plier les cier au passage Gotlib et tous ceux qui lÊont suivi pour ces 40 années © Midam, Adam / DUPUIS despotes et leurs interdictions. -

A Postphenomenological Approach to Architectonics As Terraprocess

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Dark Ecologies of Knowledges: A Postphenomenological Approach to Architectonics as Terraprocess A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies by Jason Timothy Taksony Hewitt 2014 © Copyright by Jason Timothy Taksony Hewitt 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Dark Ecologies of Knowledges: A Postphenomenological Approach to Architectonics as Terraprocess by Jason Timothy Taksony Hewitt Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Jonathan Furner, Chair This series of essays offers a critique of Information Studies, taken as a discipline largely concerned with informational objects and their representations on the one hand and the control of these same by means of other informational objects and their representations on the other. Spe- cifically, the critique put forward here attends to the ways that the common practices of Infor- mation Studies may reinforce representationalist ideologies that are historically problematic and that are likely to continue to be so into the future if allowed to persist. Such ideologies are bound up with histories of oppression, colonialism, and cognitive injustice in ways that seem likely to be undesirable to most practitioners upon consideration. The critique offered seeks to point out this conjunction of aesthetic and ethical issues in our practical epistemological constructs, open- ing out largely untried avenues of exploration with regard to our axiological habits—axiology ii being defined here as the inquiry that includes ethics, aesthetics, and epistemology—and the ar- chitectonic structures of meaning and understanding that we deploy with ever increasing density in (and occasionally as) the world.