Beer & Whisky in Upper Coquetdale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Toilet Map NCC Website

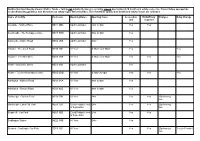

Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. Please follow appropriate social distancing guidance and directions on safety signs at the facilities. This list will be updated as health and safety issues are reviewed. Name of facility Postcode Opening Dates Opening times Accessible RADAR key Charges Baby Change unit required Allendale - Market Place NE47 9BD April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Yes Allenheads - The Heritage Centre NE47 9HN April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Alnmouth - Marine Road NE66 2RZ April to October 24hr Yes Alnwick - Greenwell Road NE66 1SF All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Alnwick - The Shambles NE66 1SS All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Yes Amble - Broomhill Street NE65 0AN April to October Yes Amble - Tourist Information Centre NE65 0DQ All Year 6:30am to 6pm Yes Yes Yes Ashington - Milburn Road NE63 0NA All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Ashington - Station Road NE63 9UZ All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Bamburgh - Church Street NE69 7BN All Year 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty box Bamburgh - Links Car Park NE69 7DF Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty of September box Beadnell - Car Park NE67 5EE Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes of September Bedlington Station NE22 5HB All Year 24hr Yes Berwick - Castlegate Car Park TD15 1JS All Year Yes Yes 20p honesty Yes (in Female) box Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

JMU Overpowers Providence 94-74; Meet Buckeyes for Sunday Showdown Dukes Wrest CAA Title in See-Saw Game

London: JMU students dd the town, Brit-style THURSDAY, MARCH 16, 1989 JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY VOL. 66 NO. 43 JMU overpowers Providence 94-74; meet Buckeyes for Sunday showdown By Eric Vazzana and 18 points and fueling a second half run John R. Craig that put the game away. staff writers Carolin Dchn-Duhr continued to play The big party got underway last night inspired ball on the inside as she at the Convocation Center as the JMU collected 24 points and grabbed nine women's basketball team spoiled the rebounds. Missy Dudley turned in her visiting Providence Friars' upset bid and usual steady game, chipping in with 20 cruised to a 94-74 victory. points and six rebounds. Dudley was also given the assignment of shutting JMU shot a blistering 60 percent down the Friars' primary outside threat from the field in the first half, including Tracy Lis. Lis shot a dismal four-for-14 going scven-for-seven to open the first and was ineffective all night. round of the NCAA women's basketball It was a JMU team effort in every tournament. The Dukes advance, to the phase of the game that left Providence second round of the tourney riding a head coach Bob Folcy searching for 12-game win streak and will face Ohio ways to stop the Dukes all night. State Sunday on the Buckeye's home What went wrong is James Madison court in Columbus, Ohio. shot, what, about 88 percent?" said JMU head coach Shclia Moorman felt Folcy. "We knew that Carolin her team would have to play medium Dehn-Duhr was a strong inside player, I tempo to win and play at "our usual knew that Dudley could shoot the intensity." jumper. -

7-Night Northumberland Gentle Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Northumberland Gentle Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Gentle Walks Destinations: Northumberland & England Trip code: ALBEW-7 1 & 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Discover England’s last frontier, home to castles, never-ending seascapes and tales of border battles. Our gentle guided walking holidays in Northumberland will introduce you to the hidden gems of this unspoilt county, including sweeping sandy beaches and the remote wild beauty of the Simonside Hills. WHAT'S INCLUDED Whats Included: • High quality en-suite accommodation in our Country House • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of Northumberland on foot • Admire sweeping seascapes from the coast of this stunning area of outstanding natural beauty • Let an experienced leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life • Look out for wildlife, find secret corners and learn about this stretch of the North East coast's rich history • Evenings in our country house where you share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: Along The Northumberland Coast Option 1 - Boulmer To Alnmouth Distance: 3½ miles (5km) Ascent: 180 feet (60m) In Summary: Head south along this picturesque stretch of coastline from the old smugglers haunt of Boulmer to Alnmouth.* Walk on the low cliffs and the beach, with fantastic sea views throughout. -

Lactic Acid Bacteria – the Uninvited but Generally Welcome Participants In

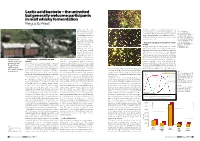

Lactic acid bacteria – the uninvited (a) but generally welcome participants in malt whisky fermentation Fergus G. Priest Coffey still. Like malt diversity resulting in Lactobacillus fermentum and LEFT: (b) whisky, it must be matured Lactobacillus paracasei as commonly dominant species by Fig. 1. Fluorescence photomicrographs of whisky for a minimum of 3 years. about 40 hours. During the final stages when the yeast is fermentation samples; green cells Grain whisky is the base of dying, a homofermentative bacterium related to Lacto- are viable, red cells are dead. (a) the standard blends such as bacillus acidophilus often proliferates and produces large Wort on entering the washback, (b) Famous Grouse, Teachers, amounts of lactic acid. after fermentation for 55 hours and and Johnnie Walker which (c) after fermentation for 95 hours. (a) AND (b) ARE REPRODUCED will contain between 15 Effects of lactobacilli on the flavour of malt WITH PERMISSION FROM VAN BEEK & and 30 % malt whisky. whisky PRIEST (2002, APPL ENVIRON Both products use a The bacteria can affect the flavour of the spirit in two MICROBIOL 68, 297–305); (c) COURTESY F. G. PRIEST similar process, but here ways. First, they will reduce the pH of the fermentation we will focus on malt (c) through the production of acetic and lactic acids. This whisky. Malted barley is will lead to a general increase in esters following milled, infused in water at distillation, a positive feature that has traditionally been about 64 °C for some 30 associated with the late lactic fermentation. This general minutes to 1 hour and the effect is apparent in the data presented in Fig. -

Alcohol Units a Brief Guide

Alcohol Units A brief guide 1 2 Alcohol Units – A brief guide Units of alcohol explained As typical glass sizes have grown and For example, most whisky has an ABV of 40%. popular drinks have increased in A 1 litre (1,000ml) bottle of this whisky therefore strength over the years, the old rule contains 400ml of pure alcohol. This is 40 units (as 10ml of pure alcohol = one unit). So, in of thumb that a glass of wine was 100ml of the whisky, there would be 4 units. about 1 unit has become out of date. And hence, a 25ml single measure of whisky Nowadays, a large glass of wine might would contain 1 unit. well contain 3 units or more – about the The maths is straightforward. To calculate units, same amount as a treble vodka. take the quantity in millilitres, multiply it by the ABV (expressed as a percentage) and divide So how do you know how much is in by 1,000. your drink? In the example of a glass of whisky (above) the A UK unit is 10 millilitres (8 grams) of pure calculation would be: alcohol. It’s actually the amount of alcohol that 25ml x 40% = 1 unit. an average healthy adult body can break down 1,000 in about an hour. So, if you drink 10ml of pure alcohol, 60 minutes later there should be virtually Or, for a 250ml glass of wine with ABV 12%, none left in your bloodstream. You could still be the number of units is: suffering some of the effects the alcohol has had 250ml x 12% = 3 units. -

The Star Inn Harbottle Near Rothbury

The Star Inn Harbottle Near Rothbury A traditional village pub with self-contained 3-bedroomed owner’s accommodation and a substantial range of adjoining stone outbuildings. The property dates from circa 1800 and is situated in the centre of an attractive Coquet Valley village. Subject to necessary consents (the property is not Listed) the buildings have potential for conversion to provide letting rooms and/or restaurant facilities. The pub currently generates an additional income from newspaper and magazine sales and there may be scope to extend the retail business. The property is freehold, a free house, and will be sold with vacant possession. turvey www.turveywestgarth.co.uk westgarth t: 01669 621312 land & property consultants Harbottle The village is situated approximately 7 miles west of Rothbury within the Northumberland National Park. Harbottle has a thriving first school and a well-used village hall. Rothbury offers a full range of services and amenities including a library, art centre, specialist shops, banks, post office and golf course. Services Mains electricity, water and drainage. Postcode NE65 7DG Local Authority Northumberland National Park Authority Eastburn South Park Hexham Northumberland NE46 1BS Tel: 01434 605555 Business Rates The current rateable value is £1,125.00 (effective 2017). Tenure Freehold with vacant possession. Viewing Strictly by appointment with the selling agents. Location Please refer to the plan incorporated within these particulars, for detailed directions please contact the selling Agents. Energy -

Otterburn Ranges the Roman Road of Dere Street 3 50K Challenge 4 the Eastern Boundary Is Part of a Fine Route for Cyclists

The Otterburn Ranges The Roman road of Dere Street 3 50K Challenge 4 The Eastern Boundary is part of a fine route for cyclists. This circular cycle route takes you from Alwinton A challenging walk over rough terrain requiring navigation through the remote beauty of Coquetdale to the Roman skills, with one long stretch of military road. Rewards camps at Chew Green and then back along the upland with views over the River Coquet and Simonside. spine of the military training area. (50km / 31 miles) Distance 17.5km (11 miles) Start: The National Park car park at Alwinton. Start: Park at the lay-by by Ovenstone Plantation. Turn right to follow the road up the Coquet Valley 20km After the gate join the wall NW for 500m until the Controlled to Chew Green. wood. Go through the gate for 500m through the wood, Continue SE from Chew Green on Dere Street for 3km keeping parallel to the wall. to junction of military roads – go left, continue 2.5km After the wood follow the waymarked path N for 1km ACCESS AREA then take the road left 2.5km to Ridlees Cairn. After up to forest below The Beacon.This will be hard going! 1km keep left. After 3.5km turn left again to follow the Follow path 1km around the forest which climbs to The This area of the Otterburn Ranges offers a variety of routes ‘Burma Road’ for 10km to descend through Holystone Beacon (301m). From here the way is clear along the across one of the remotest parts of Northumberland. -

Rothbury Thropton / Snitter Swarland / Longframlington

Please find the following Coquetdale Community Message update covering the period from the 1st to the 29th June 2015. Ten (10) x crimes were reported over this period: Rothbury Criminal Damage to Motor Vehicle - The Pinfold Occurred between 14.30 hrs and 17.45 hrs 04/06/15 A sharp instrument was used to scratch the boot of an unattended, securely parked motor vehicle belonging to a resident. Police have enquired with nearby residents following a verbal altercation, prior to the incident. Enquiries are continuing. Officer in the case (OIC) PC Paul Sykes Theft (from employer) - Retail shop in Rothbury Occurred over a period of time to be determined. CID are investigating this reported theft. OIC DC Went Thropton / Snitter Nothing of note to report Swarland / Longframlington Theft from Motor Vehicle - High Weldon Farm Occurred between 10.00 hrs 02/06/15 and 10.00 hrs 03/06/15 where a Samsung computer tablet (£400) was reported to have been removed from a securely parked, unattended motor vehicle. OIC PC Jimmy Jones Criminal Damage to Motor Vehicle - Embleton Terrace, Longframlington Occurred between 15/05/15 and 18/06/15. Persons unknown removed the vehicle fuel cap and deposited a quantity of sugar substance, contaminating the use of the diesel fuel. OIC Sgt Graham Vickers Theft - Braeside, Swarland Occurred between 01/05/15 and 12/06/15 where an electric fence energiser and battery was removed from the field. OIC PC Jack Please continue to report any person or vehicle you feel is suspicious immediately via. the 999 emergency system. Harbottle / Alwinton / Elsdon / Rothley areas Burglary OTD - Rothley Crag Farm Occurred between 00.00 hrs and 07.00 hrs 12/06/15 where offenders gained access to an insecure farm outbuilding where a red Honda quad bike, blue Suzuki quad and sheep shearing equipment were stolen. -

Roman Roads in Britain

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES !' m ... 0'<.;v.' •cv^ '. V'- / / ^ .^ /- \^ ; EARLY BRITAIN. ROMAN ROADS IN BRITAIN BY THOMAS CODRINGTON M. INST. C.E., F.G.S. WITH LARGE CHART OF THE ROMAN ROADS, AND SMALL MAPS LY THE TEXT SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, LONDON: NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. 43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.G. ErIGHTON ; 129, NORTH STREET. 1903 PUBLISHED UNDEK THE DIRECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMAHTTEE. DA CsHr PREFACE The following attempt to describe the Roman roads of Britain originated in observations made in all parts of the country as opportunities presented themselves to me from time to time. On turning to other sources of information, the curious fact appeared that for a century past the literature of the subject has been widely influenced by the spurious Itinerary attributed to Richard of Ciren- cester. Though that was long ago shown to be a forgery, statements derived from it, and suppositions founded upon them, are continually repeated, casting suspicion sometimes undeserved on accounts which prove to be otherwise accurate. A wide publicity, and some semblance of authority, have been given to imaginary roads and stations by the new Ordnance maps. Those who early in the last century, under the influence of the new Itinerary, traced the Roman roads, unfortunately left but scanty accounts of the remains which came under their notice, many of which have since been destroyed or covered up in the making of modern roads ; and with the evidence now avail- able few Roman roads can be traced continuously. The gaps can often be filled with reasonable cer- tainty, but more often the precise course is doubtful, and the entire course of some roads connecting known stations of the Itinerary of Antonine can IV PREFACE only be guessed at. -

Diocese of Newcastle Prayer Diary October 2020

This Prayer Diary can be downloaded each month from the Newcastle diocesan website: www.newcastle.anglican.org/prayerdiary Diocese of Newcastle Prayer Diary October 2020 1 Thursday Diocese of Botswana: Cathedral of the Holy Cross: Remigius, bishop of Rheims, apostle of the Celestino Chishimba, Dean and Archdeacon Franks, 533 (Cathedral) and Fr Octavius Bolelang Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, social reformer, 1885 Alnwick Deanery: Deanery Secretary: Audrey Truman Anglican Communion: Finance Officer: Ian Watson Diocese of Perth (Australia) Abp Kay Goldsworthy 4 SEVENTEENTH SUNDAY AFTER TRINITY Diocese of Chhattisgarh (North India) Porvoo Communion: Bp Robert Ali Diocese of Haderslev (Evangelical Lutheran Diocese of Chicago (ECUSA) Bp Jeffrey Lee Church in Denmark) Diocese of Botswana: Diocese of Liverpool Metlhe Beleme, Diocesan Bishop Diocese of Monmouth (Church in Wales) Alnwick Deanery: Anglican Communion: Area Dean: Alison Hardy Anglican Church of Tanzania The Mothers’ Union: Abp Maimbo Mndolwa The work of MU Diocesan Secretary Sandra Diocese of Botswana: and other members with administrative St Barnabas’ Church, Old Naledi (served by roles the Cathedral of the Holy Cross) 2 Friday Alnwick Deanery: Benefice of Alnwick St Michael and St Paul Anglican Communion: Vicar: Paul Scott Diocese of Peru (S America) Curate: Gerard Rundell Bp Jorge Luis Aguilar Readers: John Cooke and Annette Playle Diocese of Chichester Bp Martin Warner Diocese of Botswana: 5 Monday Theo Naledi, retired Bishop Anglican Communion: Alnwick -

The Citie Calls for Beere: the Introduction of Hops and the Foundation of Industrial Brewing in Early Modern London

BREWERY The Journal is © 2013 HISTORY The Brewery History Society Brewery History (2013) 150, 6-15 THE CITIE CALLS FOR BEERE: THE INTRODUCTION OF HOPS AND THE FOUNDATION OF INDUSTRIAL BREWING IN EARLY MODERN LONDON KRISTEN D. BURTON But now they say, Beer beares it away; how this additive allowed brewers to gain more capital, The more is the pity, if Right might prevaile: invest in larger equipment, and construct permanent, For with this same Beer, came up Heresie here; industrial brewing centers.4 The resilience of beer made The old Catholique Drink is a Pot of good Ale.1 beer brewers wealthier and allowed them greater social John Taylor, 1653 prestige than ale brewers ever experienced. Due to the use of hops, the beer trade in London quickly supplant- ed the ale trade and resulted in a more sophisticated, The cleric William Harrison’s 1577 record of commercialized business. Though London was not the Elizabethan England includes candid comments on the first location for the arrival of hops in the British Isles, important place hopped beer had in English society.2 it did grow into a commercial center for brewers who Beer was a drink consumed by members of all social became the primary exporters of beer in Europe by the stations, and Harrison notes that it was the preferred seventeenth century. beverage of the elite. Compared to the favorable presen- tation of beer, un-hopped ale appears in Harrison’s Growth in the commercial trade of hopped beer origi- account as an undesired brew, described only as an ‘old nally occurred during the late thirteenth and early and sick men’s drink,’ whose force could not match the fourteenth centuries in northwestern Europe, but the strength or continuance of hopped beer.3 These brief active use of brewing with hops first appeared on the comments, documented nearly two centuries after the European continent as early as the ninth century.